Making it Rain: How Defenses 'Option' The Blitz

As the offensive side of the ball has evolved into you-go-here-I-go-there football, defenses have countered with post-snap options of their own

When we think of ‘option’ football, we primarily think of the offensive side of the ball. We think of the you-go-here-I-go-there designs that teams run in their RPO packages or through the quarterback reading a defender in the run game.

But in the modern game, defensive football has become a series of post-snap options, too. If they’re going to wait and read us, why don’t we wait and see where the ball is going before we run our stuff?

The most obvious: pattern-matching, a hybrid style combination coverage – a ‘zone match’ in theory. Rather than dropping to a specific spot (or zone) a defender is given more steadfast rules. He is set to drop to a spot, but if a receiver comes into his zone, he relates to his route, even if he then departs the zone — shifting from zone to man coverage. Teams — like Alabama and the great Seattle sides — will run this as a press-then-trail technique, the cousin of bump-and-run man coverage. The most common practice: A corner is lining up at the line to drop into a deep-third zone, but he will relate to vertical release from the receiver opposite him to take away any vertical plays down the field. If that same receiver releases underneath, the corner is liable to let him go and then drop back into his zone, with a little tap on the way to disrut the timing of the release.

The defender has — hey! — an option. There are innumerable coverage-specific principles for pattern-match coverages. It’s difficult, complex stuff – more commonplace at the college level where coaches have three or four years with the same defensive players.

‘Optioning’ blitz and pressure looks are increasingly becoming the norm, too. You’ve probably heard all about simulated pressures, zone-pressures, creepers, loaded fronts and the like. All are, at a minimum, option adjacent. It’s about reading and reacting to whatever concept is coming out of the offensive backfield, and whatever that offense is doing with its protection upfront.

Defensive coaches are as adamant as ever about making it look like five or six defenders are attacking on a ‘blitz’ when in reality they’re sending only four players on a ‘pressure’, only those four guys could come from any number of spots.

Pressure looks and the principles of such looks are becoming increasingly complex schematically (though taught in a way that makes them easy to digest for the players running the). But there are simpler option-style blitzes, too. And, sometimes, the old way of doing things remains the most practical. A favorite of coaches at all levels: The Rain Blitz.

It’s a style that originates — as so many of these things do – from Nick Saban’s time with the Dolphins.

(This is where I pause to point out that while it’s fun to dump on Saban’s time in Miami – the way he left, the Drew Brees decision, forcing players to tie shoe laces, etc. – Saban was so far ahead of his time with what he was running at the pro level. His defense pushed the boundaries on what was considered possible; all of which has now spread throughout the professional game.)

So much of the Saban doctrine is about morphing and shifting post-snap to give his defense the best possible chance to shutdown whatever the offense is running. The whole conceit of pattern-matching was to give Saban and Bill Belichick (then his boss with the Cleveland Browns) a chance to live in both worlds – to be able to gain some of the benefits of living in two-deep safety looks while also building an eight-man wall against the run. They could morph and shift depending on the offensive play design after the snap rather than tipping their hand before it.

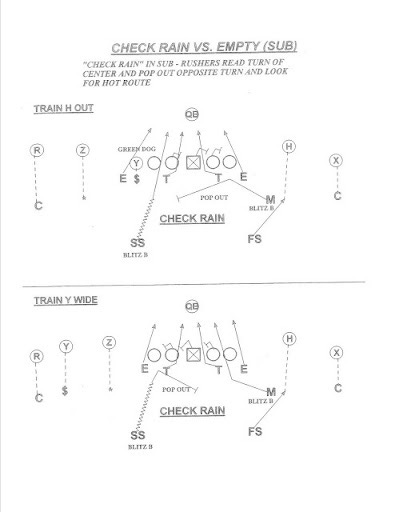

It’s a similar idea with Rain blitzes. The base idea: To have two landmarks on defense split between two defenders. One: Blitzes the backfield. The other: Sits in an underneath zone as a ‘Rat’ defender. But rather than pre-ordaining the spots, the defenders take their cue from the protection. Namely: The center.

Back when Saban was first incorporating such designs into his set-up, he would roll a safety down towards the line of scrimmage as part of his three-match package; or it would be a check vs. empty with zero coverage played behind. The long and short: The safety and a linebacker would each read the release of the center. If that center moved to wall off the linebacker, the safety would blitz; if the center slid to the safeties’ side, the linebacker would blitz and the safety would sit down in the hole.

Over time, Saban, Belichick, and the branches that have fallen off those trees have continued to iterate on the basic idea. Kirby Smart’s Georgia has mauled fools (most notably in their big comeback against Baker Mayfield and Oklahoma in the college football playoff semi-final) by making Rain blitzes a heavy part of their early-down package.

Smart, Mel Tucker, and the coaches from the more Georgia-centric tree are happy to bring such option designs from depth. Rather than read the center exclusively on such looks, Smart will have a pair of off-ball defenders (be it a pair of linebackers or a linebacker and safety) read the slide of the line. If the line slides right, the left-sided defender (from the offenses vantage point) attacks the vacated space. If the slide is left, the defender lined up off the ball to the right-hand side fires.

Importantly, Smart and co. kept five guys in that specific blitz look. It’s a ‘Gap’ blitz – not a pressure - with the interior down lineman clogging up as much space as possible inside, both firing from outside the shoulder of the guards towards the two A-Gaps. Eat those up (and with the caliber of athletes Georgia and Alabama are working with upfront, they do) and the defenses forces the line to play three on two inside – both guards and the center occupying the interior linemen. If the defense adds both outside guys into the fit – two ends or a pair of ‘backers – then there will be an open gap somewhere for the off-ball defender to attack.

Coaches continue to constantly tweak the base concept depending on the upcoming opponent and the talent on their respective rosters. Belichick, Saban and Smart all started to run the concept with mugged linebackers rather than with players back off the ball. Meaning: They would walk linebackers down to the line of scrimmage and stand them between gaps.

The “Double A-Gap” look is the classic design, run by every DC in the land but popularized in the NFL by Vikings’ head coach Mike Zimmer. Teams walk a pair of linebackers down into both A-Gaps, which forces the offense to commit its protection. Either the offense sets up to block both interior players, believing its quarterback can get the ball out ‘hot’ before a defender flies in off the edge. Or the offense keeps an extra piece into block, often a running back or a wing lined up directly in front of the linebacker behind a guard.

That alone constitutes a ‘win’ for the defense. They’re not only taking an eligible receiver out of the concept, but they’re forcing the offense to show to reveal its protection hand, which opens up the chance for on-the-field calls to attack five-on-six protection. That’s when all the loops and stunts and fun and games can kick in.

Because of the numbers game, the Rain design has become a go-to for teams against empty sets, with no extra pieces in the backfield. From that look, with six defenders up on the line of scrimmage, the center has to commit somewhere at the snap. Where he goes, that defender drops out, and the player on the other side attacks, hopefully with a free run to the quarterback. And that’s why the double A-Gap look has become the popular foundation for such blitz looks: The offense has no time to recover. That defender isn’t coming from depth. He’s right up on the line of scrimmage, right in your face, slap-bang in the middle of the line. It’s the quickest path to the quarterback.

Over the past two-to-three seasons, as the game has evolved, college teams and the NFL have started to splinter on Rain designs. In the college game, due to the talent disparity between the very best and the very good and the volume of spread formations vs. the more condensed sets in the pros, Smart and Saban have started to embrace more of a four-man ‘pressure’ style within their traditional Rain package. In that way, the Rain blitz has morphed into the Rain pressure. It allows them to still option the center while not investing five defenders in the blitz. They still commit four, as they would with a traditional pass-rush, which allows them to keep seven defenders out in coverage. The difference: They know the interior blitz guy has an advantage, for he’s only attacking if the center slid away from him.

It’s a best of both worlds’ situation. The team can get quick, interior pressure – even if a back is kept in to block, it makes the pocket all sorts of muddy – while dropping an extra body into coverage, right in the low hole where the quarterback would typically find a quick outlet ball.

Pro teams are embracing the simulated pressure era like never before (at least all the different exotic designs, if not the raw percentage of how much they’re running a zone or simulated pressure). But given the parity of talent, teams still look to blitz – sending five or more defenders – a whole bunch more than their college compatriots. It’s a heavier investment, but it’s often a necessary one.

Double A-Gap looks remain the order of the day. A coach may option his linebackers, send both, drop one out to a predetermined spot, or drop both out, bringing a looper into their space or slanting his two interior down linemen into that vacated space before bringing pressure from elsewhere. The possibilities are endless!

Bill Belichick and the Patriots are dabbling in a little bit of everything this season. But Belichick – as he often does – continues to embrace the simplicity of the Rain structure. You hit ‘em where they ain’t. It doesn’t need to be a whole lot more detailed than that.

For the uber-nerds: Belichick’s Rain ‘check’ is literally him gesturing rain with his hands on the sideline.

A tough one to crack from the league’s foremost intellectual.

The Patriots’ defense is good-not-great this year, ranking 12th in EPA per play. But it’s not for a lack of pressure. Belichick’s defense is generating pressure on 62 percent (!!!) of all third downs, per NFL Next Gen Stats. That’s not a typo. Sure, the Pats have played a (mostly) ropey slate, but that doesn’t account for all that pressure.

Belichick is bringing the heat this season, often from the aforementioned ‘loaded’ fronts, which involves the team loading up one side of the defensive formation and planting a nose tackle (or a mugged defender) over the head of the center. That forces the offensive line to commit its protection to one side of the other.

The Patriots have consistently found ways to scheme up free runners on the quarterback, which is why the Patriot Way calls for not paying a one-off pass-rusher a bonkers amount of cash but spreading that cash around a whole bunch of ‘plus’ players with different body types, those who can bounce between all the different pressure looks needed on a gameplan-to-gameplan basis.

Double A-Gap looks continue to be a go-to for Belichick and his staff in obvious passing situations, though. After dabbling with a dime ‘backer and linebacker in those spots, Belichick has returned to the vintage look: He sticks two big-bodied inside run-pluggers in the two spots on either side of the center. In fact, rather than dropping a slender body into the other A-Gap, Belichick has rolled with an augmented look to his base package, planting a down lineman in one of the A-Gaps while standing up a linebacker to the other side. It fits snuggly into the Belichickian mantra of showing different looks but using the same design — making it easier to teach but extra information for the offense to digest.

In that way, Belichick can get to all his mugged goodness while keeping his base personnel on the field playing from their early-down, odd-front defensive base. And yet the principle is the same: If the center pops your way, you pop out:

Still: The double ‘backer shot remains Belichick and the Patriots’ flavor of choice. Two linebackers align on either side of the center. Two three-techs drive to the inside. Whoever the center tries to pick up drops out, who is left alone drives to the quarterback:

It’s simple but effective.

Belichick continues to build on and evolve the look mid-game, setting up his own tendency before breaking it later in the match-up. Against the Cowboys, Belichick unloaded it all. He started the game rolling with the typical set:

Then he toggled to a late-arriving variation, moving Matthew Judon, the team’s top pass-rusher, from the outside to the inside. Rather the lining up in the A-Gap pre-snap, Judon went for a little before-the-snap stroll, moving from an overloaded alignment to just in the A-Gap at the snap.

Cowboys’ center Tyler Biadasz had eyes only for Ja’Whuan Bentley (#8) who was lined up in the A-Gap from the break of the huddle. As Biadasz shifted to wall off Bentley, the linebacker dropped out, with Judon thudding into the A-Gap just as the ball was snapped. The center reacted late, the guard clamped across, and Judon was able to slip out to his right, get off the block, and put pressure on Dak Prescott, who was forced to throw the ball away.

It was a tidy change-up and the sort of week-to-week iteration that Belichick has layered on top of a most basic of designs. The teaching point doesn’t change, just the rhythm of the play. And nothing changes for the Cowboys. They know such an option look is coming; the Patriots had run four such you-go-I’ll-drop, double A-Gap mugged looks on the Cowboys’ first drive. But by kind of, sort of changing the angle and tempo of the play, it caused disruption.

Belichick also dropped this doozy:

I mean, maaaan. That is spicy. That is mean.

As mentioned, Belichick consistently brought the one-man-go-one-man-out, read-the-center blitz. So what’s the next best thing, once the Cowboys start getting a read on the look, I mean? Drop both guys out, right? Have the offense commit its resources to sealing both would-be blitzers — Maybe.

The offense could also look to build-in concepts that play off the fact that you – the offense – can dictate the blitz. If you know the center sliding right means the left guy will blitz, you can attack that, either by replacing the hole with a trap block, running some form of insert zone, or dropping a slip-screen behind the blitzer.

So how did Belichick respond? He ran a ‘double bluff’. Both guys dropped out… THEN they both looped:

At the same time as the linebackers loop, here comes a run-of-the-mill stunt to help things along: The two interior linemen serve as mashers, attacking outward to draw a guard-tackle double team; on the outside the two end-men on the line of scrimmage (EMOL) come screaming around the corner to replace the two linebackers. Oof.

It was a six vs. six pre-snap picture – the line, plus a back in the backfield. When Prescott hits the top of his drop, the Patriots had two free rushers (both loopers) in on Prescott. Prescott was able to get rid of the ball (because he’s Dak Prescott!) but it was broken up for no gain – and the quarterback absorbed another hit as thanks for his good work.

I’ve written about this a ton: The best coaches, more specifically the best gameday play-callers, are all about layering concepts. They use one play to unlock another. They use set-up plays, concepts and designs early in the game so that they can run pay-off plays once the other side starts adjusting.

There are so many aspects of Belichick (philosophically, team-building, overall defensive nous) that are brilliant. But part of his excellence is in building more sophisticated structures on top of simplistic base constructs.

Belichick uses his own reputation as a defensive czar against the opposing offense. He runs simplistic option-blitz designs. As the offense adjusts, he hits them with the more intricate, creative stuff. And as the opposing OC and quarterback start worrying about whatever Bill has up his (cut-off) sleeves, he returns to the basics, because those are often the simplest ways to execute what it is he wants to execute.

If the opposition is going to overthink things for you, hit them with the easy stuff.

On the offensive side of the ball, coaches are leaning into the idea that they can snap the ball and then figure it out. They’re building an ever-increasing option network into everything they do: The run-game, quick game, intermediate dropback game, play-action designs, and shot plays.

Defenses have countered by… matching what is the offense is doing. If they’re going to spend their time figuring out what to do post-snap, the best way to defend it is to wait to see what they’re doing post-snap and adjust on the fly.

If you enjoyed this piece, you can become a premium subscriber of The Read Optional to receive three pieces of content a week directly into your inbox and access to the back catalogue.