Condense-to-Expand: The Evolution of Justin Herbert, Joe Lombardi and The Chargers Offense

What do you do when you’re handed the most gifted young quarterback in the game, non-Mahomes division? You hand him the mother lode.

It’s tough for a young quarterback to go up against Steve Spagnuolo.

The Chiefs DC likes to muddy the picture at all levels. Players bounce and move and rotate pre-snap. Then they bounce and move and rotate some more post-snap. A young QB goes through his pre-snap checklist. He might check from a bad play into a good one based on the pre-snap picture, and then, all of a sudden, here comes both safeties screaming down, flying untouched to the football.

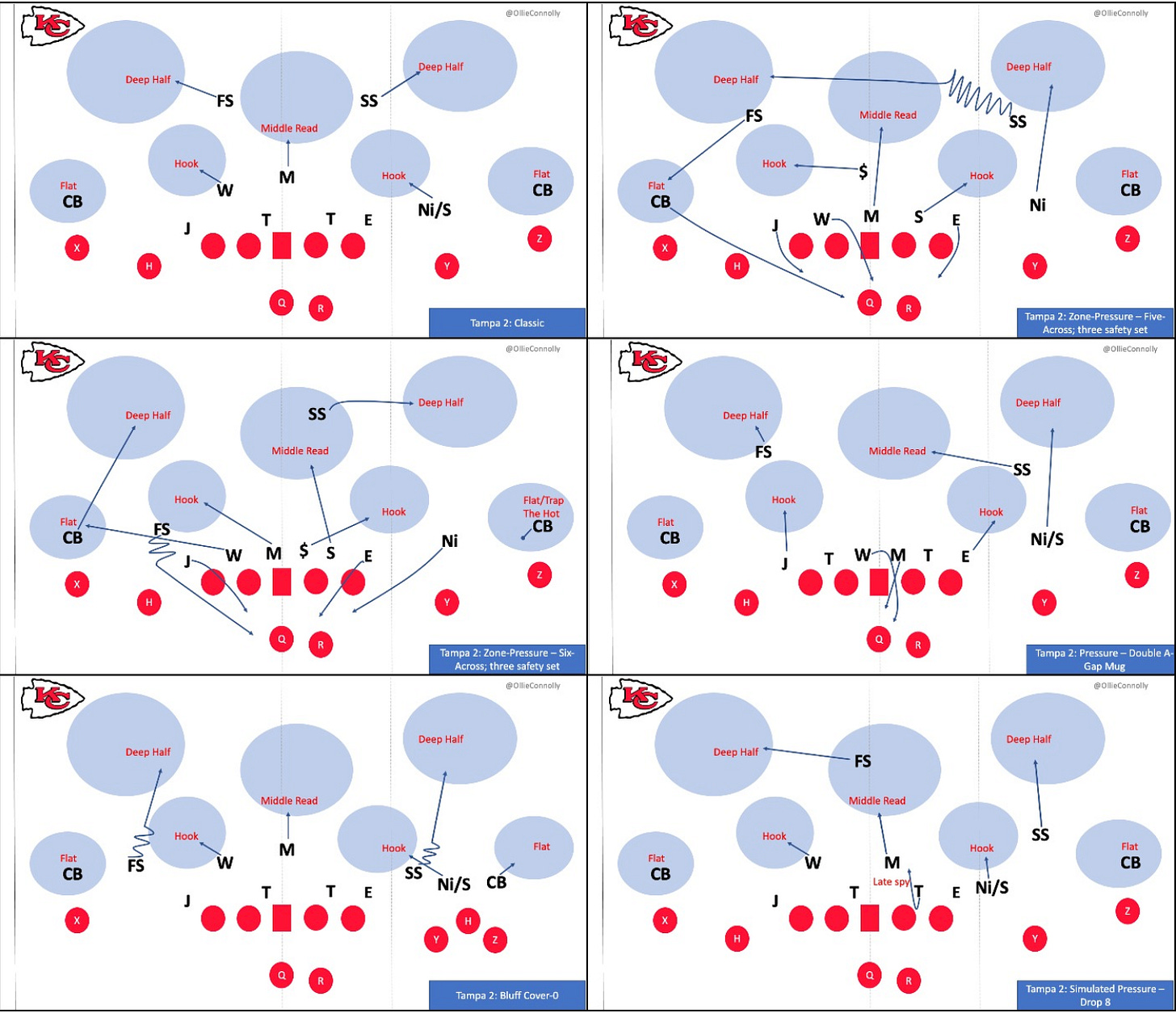

Spagnuolo wants to base out of Tampa-2. That’s his thing. You probably know all about the vintage Tampa-2 design, the one made famous by, well, Tampa, but that also caught fire with the Chicago Bears and Brian Urlacher.

In the traditional setup, Tampa-2 functions more as a pseudo-three-deep coverage than the traditional cover-2. The two deep safeties — as ever — split to each cover half of the field, while the middle linebacker ‘runs the pole’, darting from his spot somewhere near the line of scrimmage to a zone between the two safeties. The idea is to take away the throws that traditionally torch open-field/split-safety looks: post routes, overs, late-arriving digs — anything that targets the ‘high hole’.

Spagnuolo embraces the classics. But he also runs what one can only describe as some crazy-ass bleep.

Spagnuolo is running a Tampa-2 ice cream parlor. And there So. Many. Different. Flavors.

The Chiefs can rush four and drop seven. They can drop eight. They can send pressure. They can simulate pressure, showing a blitz and then dropping out. They’ll mug the interior gaps, standing a couple of linebackers (or safeties) up inside, and then drop those guys out to a different spot every damn time. They’ll walk everyone down to the line of scrimmage. They’ll bounce everyone out. They’ll play with a six-across front. They’ll play with a five-across front. They’ll run it from a three-safety set, but mix up the landmarks for those safeties on a snap by snap basis. Sometimes the middle safety is the middle-read defender; sometimes he slides across into one of the 1/2 field zones.

The possibilities are (almost) endless. If you can dream it, Spags is running it.

The luxury of having Tyrann Mathieu means that Spagnuolo can do things like — Oh, I don’t know — bounce the safety from one side of the field all the way over to the other deep-half, first spinning to the middle of the field to show a man-free/cover-3 look then planting and firing to the other deep outside zone.

Come on, people! That’s just mean.

And that’s not it: Even if the call is the same – everyone is going to the same spot from the same personnel grouping and same formation – the starting point might be slightly different. Maybe Mathieu does everything the same but he shuffles forward a couple of paces on one snap and then backs away on the next.

It makes the read hazy for the quarterback. The checklist goes something like this:

First: You have to figure out if it’s Tampa-2.

Then: You have to figure out who’s spinning and where they’re spinning too.

Then: You have to ID where Mathieu is. You always – always – need to know where Mathieu is.

Once you’ve done that, then you can start bouncing through your reads. n Making those reads in real-time is the NFL’s highest art. It requires a second-by-second mapping of 21 other humans in motion – and the brainpower to think one step ahead of them.

The hope for Spagnuolo, of course, is that he confuses the quarterback into making an error or that he paralyzes the thought process so much that pressure gets home before the quarterback has completed steps one through three.

I know what you’re thinking: If the post-snap picture is the same, does it really matter? If the coverage shell remains 2/3 deep with four underneath (with the odd five-under mixed in) and those players are zooming to the same spots, why does it matter who ends up in that spot and where that player started?

The issue is throwing windows. Depending on the rotation, what is open and then closed is different: If a player starts and stands in the middle-read spot, that’s different than if he’s bouncing from the edge of the line of scrimmage or the middle of the line of scrimmage or anywhere else on the field. You might have the right route combination called to beat cover-2, but that’s no good if your initial read is to slam the ball into backside the post-route and it’s the weakside safety that’s sliding back into the high hole.

Then there’s the matchup puzzle: If Nick Bolton — a linebacker — turning and running to the high hole, then, yeah, you’re going to take that matchup every time. If it’s Mathieu buzzing from one side of the field to the other, there might be a hitch in your step.

Such an overload of information can fry the brain of even senior quarterbacks. For young QBs arriving from a largely static college game, it can look like a different sport entirely. Wait, they’re allowed to do that?!?!

And that makes what Justin Herbert and Joe Lombardi did last Sunday in Arrowhead Stadium all the more impressive.

Lombardi’s message to his budding star was clear: Bleep allllllll of that. Bleep the rotations. Bleep the position switches. Bleep the different fronts and different safety looks. Bleep the real pressures and the fake pressures.

Lombardi’s decision: Go fast. The Chargers cranked up the tempo, making it difficult for Spagnuolo and the Chiefs to rotate a whole bunch. To move and rove takes time – and energy. If the offense isn’t getting in the huddle or is moving in a so-called fastball offense, it’s hard to set up those bluffs and fakes. You’re tired from running the last play; you don’t want to be hauling from one side of the field to the other just to set up in another deep-half zone. You’re not going to get there in time, or you’ll miscommunicate the call and find yourself standing in the same spot as your teammate.

The best way to sow doubt is to act early, before a defense is set.

By revving up, Lombardi put the Chiefs in a bind: Should they stay static and play straight-up or try to communicate and move, but in doing so risk miscommunication and a coverage bust?

Spags opted for the latter. It didn’t work:

That’s the Chargers’ first touchdown of the day. It’s nothing inspired. The Chiefs have a beat on it; it should have been covered. But the ball was snapped before Kansas City could figure out who was supposed to go where. At the snap, Daniel Sorensen (#49) and L’Jarius Sneed (#38) made a beeline for the same spot.

Bust. Touchdown.

Throughout the first half, Lombardi and Herbert modulated the tempo. Sometimes fast, sometimes slow. Sometimes with a huddle, sometimes without. It made it tough for Spagnuolo and the defensive staff to get a read on what to do: Should they ditch the fancy rotation stuff altogether or make a decision snap to snap?

They want to run that stuff. Given their second and third-level talent, they kind of, sort of need to run that stuff. Playing straight up against that group and that quarterback… not good.

As soon as they crossed midfield, the Chargers would leap into their turbo package. The Chiefs couldn’t keep up:

What we have right there: A ‘three-point’ defense. As in: there are three guys stood around pointing at each other not knowing where they – or their teammates – are supposed to be. The Chargers once again got the call in before KC could reset what it wanted to do on the back-end.

The defense over-rotated, then out-leveraged itself as the Chargers sent a man in motion, leaving Austin Ekeler open to leak out of the backfield. Bust. Touchdown.

Spagnuolo adjusted. He started to limit his rotations -- and the Chiefs held up okay! But the damage was done. As one-off, take-away-what-they-do-best, put-our-guy-into-a-position-to-succeed plans go, you will struggle to find a better one this season.

There are so many layered storylines to this NFL season: What’s going on with the rookie quarterback class; what happened at the end of the Patriots dynasty (we’re still doing that?); Sam Darnold escaping the Jets-ness of it all; the Seahawks’ imploding defense; Sean McVay and Matthew Stafford going scorched Earth on everyone.

But don’t overlook the most glorious, Gamepass habit-altering development of them all: Justin Herbert and Joe Lombardi have figured it out.

And by ‘it’, I mean this whole offensive football thing. In three short weeks, Lombardi and Herbert have fused together all that is right and good about the modern pro-offense, sprinkled some traditional trappings on top, and set to work building something that is going to be pretty special pretty soon.

Like some sort of schematic cat, Lombardi has lived nine different lives at this point. A mainstay in New Orleans throughout the Sean Payton-Drew Brees years, Lombardi saw up close and personal the evolution from spread-‘em-out, to isolate-and-attack, to confuse-and-clobber in real-time.

With Brees, the Saints were always at the forefront of offensive innovation – having a Hall of Famer will do that for you. The first iteration of the Brees-Payton-Lombardi offense (in that order) was a spread, bombs-away marvel. It was five out. It was hi-low concepts, attacking all levels of the defense on all concepts, if at all possible.

Defenses like to add layers to their defensive shell – that’s the general goal. So the Saints added as many levels to their passing concepts as possible. Someone, somewhere, will find space between the lines – at least that was the theory.

And it was expansive. The Saints would run some fresh wrinkle, some subtle tweak, week-to-week, in all facets of the game. Every package, every concept, changing ever-so-slightly so that no one could get a beat on the thing. No matter the in-game adjustment, Payton and co. always had a counter.

Then came the isolation years. As Jimmy Graham’s influence grew, the Saints shifted from a ‘concept’ based team – with a whole bunch of intersecting routes and nifty combinations – into a matchup team. They would get into 3x1 sets, isolate Graham on one side of the formation and read it out from there. If they doubled Jimmy, well then it was one-on-one on the other side of the field. If they went one-on-one to Graham’s side, then Brees would bet on His Guy to win. If the defense sagged off and stuck a safety to each side of the formation, Brees would check to a run. Easy yards. Easy scores. Easy football.

When Lombardi made the shift to Detroit as the Lions’ OC, he took the isolate-and-attack philosophy with him, using Calvin Johnson in place of Jimmy Graham.

It worked! (Anything with Calvin Johnson would work) Until it didn’t. Teams started to get a read on the, umm, minimal structure of the playbook. Minimalism is great when a defense cannot find answers; it’s a problem once you’ve been figured out and cannot – or do not have the pieces to – adapt.

The end of Lombardi’s run in Detroit was ugly, a stylistic, structural mess compounded by in-fighting and debates about differing ‘philosophies’.

When he returned to New Orleans, Lombardi was treated to something new, a fresh mode of operating. With Brees’ arm on the wane, Payton was embracing the misdirection lifestyle. The Saints put big bodies on the field. They played from two-back sets, multi-tight end formations, extra offensive linemen on the field. They got big. They shrunk the field.

The Saints would hammer fools in the run-game, running a little bit of everything – gap, zone, pin-pull, misdirection, all five-lineman able and willing to pull, climb or seal. They fashioned as complex and diverse a run-scheme as there was in the NFL.

You name it, they’d run it. But cheat up on those fancy run actions (pre- or post-snap) and Brees was still liable – antsy, even -- to pull the ball and toss the thing over your head. Those richly-layered passing concepts were still there, ready and waiting in the background.

So what do you do when you walk away from the Institute of Drew Brees after a decade and you’re handed the most gifted young quarterback in the game, non-Mahomes division?

You hand him the mother lode.

Lombardi and Justin Herbert are not messing about. There’s nothing cute or nice about the Chargers’ 2-1 start. This is not a learning or growth year for Herbert. There’s no talk of bedding in a new system: The coach has handed Herbert everything. A little of this from the early Saints years; a little of that from the mid-years; some of that from the later years; some new stuff that tracks with the trends across the league.

Lombardi has compressed all three Saints eras into three weeks.

Herbert has responded. Through three weeks, only Dak Prescott and Tom Brady have looked as comfortable and aggressive as the second-year man. That sounds trite or vapid, but it matters.

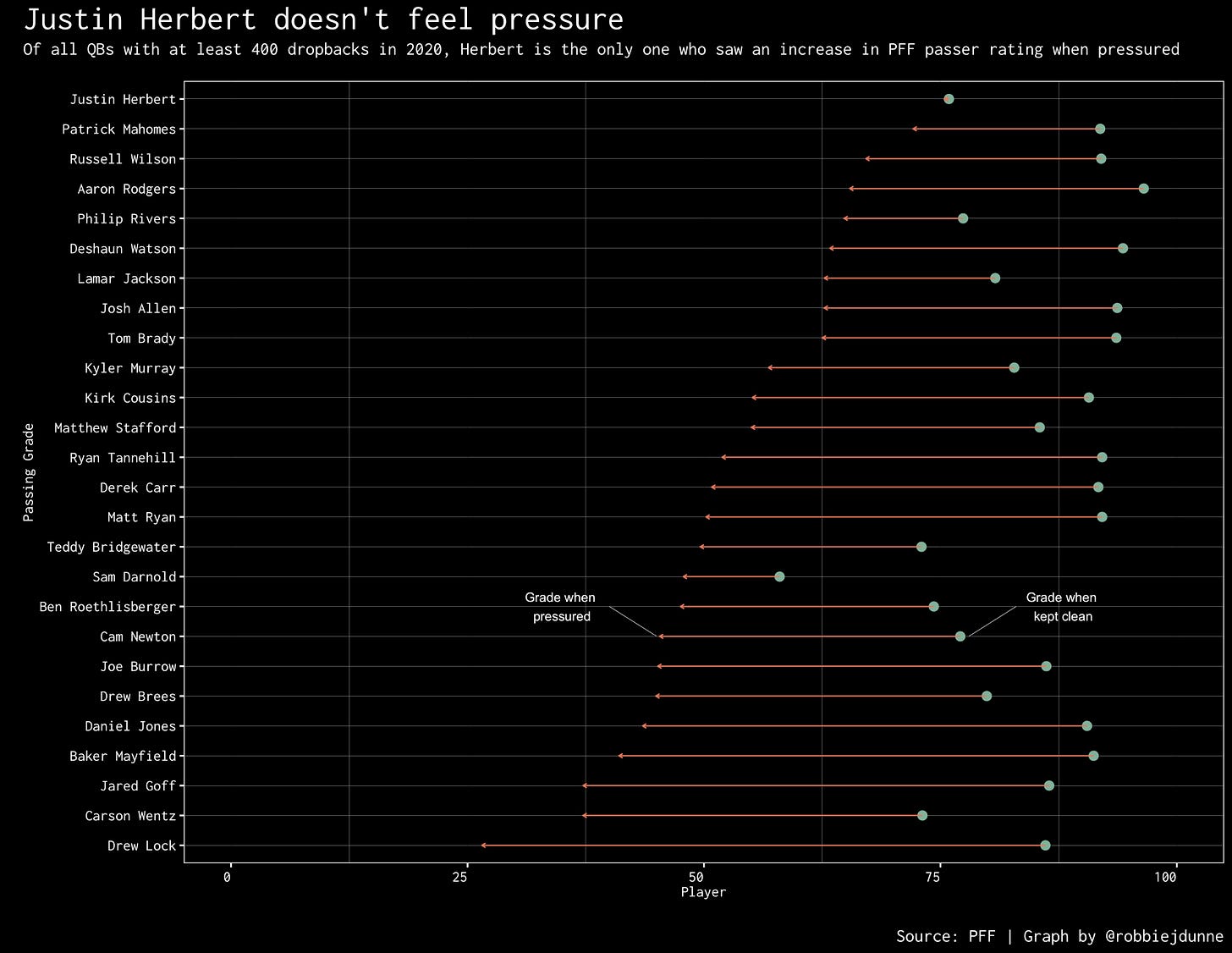

Herbert has learned to take the comfortable play, to settle down, to let a play breathe a little when it needs it. Last year, Herbert was better off-script than he was on-script. He was better pressured than when not pressured, by a fairly significant margin. Herbert’s passer rating when not pressured was 97.7 percent, six points below the league average, per Pro Football Focus. That leapt (leapt!) to 99.4 percent when he was pressured, a full 34 (!) percentage points above the league average, which feels like a typo.

To call that unusual would be like calling a bilingual tortoise unusual. That. Does. Not. Happen. It shouldn’t happen. Even the greatest to ever do it are typically much better when not pressured than when they are pressured because — duh — there’s no one in their face and they have the time to survey the landscape before making a decision.

2020 Herbert played instinctually. He looked. He fired. If he didn’t like the first look, he shuffled a little, broke the structure, then fired. It was effective, but it’s tough to maintain any kind of stability over the course of a ten-to-fifteen-year career when you’re that much better breaking the structure than playing within it. Patrick Mahomes, Aaron Rodgers and Russell Wilson all thrive out-of-structure, but it’s icing on the top of the sweetest cake. They excel first and foremost within the scheme.

Herbert has reached that level this season. Through three games, he has completed 72 percent of his passes when kept clean, per PFF. He has thrown five touchdowns to three interceptions, averaging eight yards per throw.

And forget about blitzing him, too. So far this season Herbert is a mind-boggling 25-of-33 for 308 yards against the blitz, throwing two touchdowns, no interceptions and averaging 9.3 yards per attempt. Like Kyler Murray, he’s joined the vaunted do-not-blitz club. He has almost entirely removed the fat from his game. The what-are-you-thinking plays are all-but gone:

Go through all the options there. Count them. Herbert has four or five (maybe six) opportunities to make a bad decision. They’re tantalizing. They’re right there. This is a guy who can make any throw from any kind of platform or arm angle you can imagine. Go on. Do it. Throw it! It’s a veritable Garden of Eden of shitty coverage reads. But Herbert doesn’t bite. He moves and looks, moves and looks some more, moves and looks again, and decides to take the easy yards on the ground; he lives to play another down.

I count two dopey decisions this season: One vs. the Chiefs; the redzone pick vs. the Cowboys.

I remind you: Herbert is 23-years-old. Mistakes should happen all the time, particularly given his instinctive want to break out of the schematic confides.

Even iffy balls now come with understandable explanations:

That’s a miss. It’s Herbert throwing to a landmark and expecting his guy to get there. He didn’t. Herbert should hit the throw. He didn’t. But it’s not the kind of triple-take-worthy decision that was dotted throughout his rookie year.

Everything from inside the structure looks natural. It looks comfortable. It looks easy. The ball is out on-time and in-rhythm. There’s no hitching; there’s no need to freelance. He’s throwing with anticipation:

How? Lombardi changed the structure.

The first thing you need to know about the 2021 Chargers offense: They build everything out of condensed formations. Through three weeks, they are the narrowest offense in the league, breaking the Rams monopoly on the very concept of narrow-ness. The Chargers average the shortest starting distance between their two widest players on offense, according to NFL Next Gen Stats:

Lombardi took a decade-worth of Saints goodness and dressed it up in a vintage, Manning-esque, condense-to-expand package.

Rather than play in traditional ‘spread’ formations with receivers littered across the field in wide (or ‘plus’) splits to stress the defense, the Manning offense flips the notion in its head: To spread into open space after the snap, not align in it before the snap.

The Chargers are utilizing all-manner of formations, personnel groups and concepts. Yet it all comes from tight, bunched-up looks:

By shrinking the formation, Lombardi has opened up a ton of things: The team can get more creative in the run game, adding extra gaps along the line of scrimmage wherever necessary and using Keenan Allen and Mike Williams – big-bodied receivers – as legitimate perimeter blocking threats.

It makes life easier in the dropback game, too. With everyone bunched up on the line (often in bunch formations) it’s easier to run quick, man-beater concepts, with receivers crisscrossing in the middle of the field or switching their releases at the line of scrimmage. The close proximity of the receivers makes all of that man-beating fun and games happen that bit quicker. So far, Herbert’s average time to throw on throws under 10-yards is 2.1 seconds, among the quickest in the league.

The Chargers get into big sets, threaten to run the ball or to deliver a steady dose of crossers… and then they don’t. Defenses back up or sag off in zones. They don’t want to sit in man-coverage and have their cornerbacks sorting through the middle-of-the-field clutter. The Chargers pepper the sidelines and underneath zones.

Keep backing up to cover that space outside, though, and there’s still all that room inside to hit in the middle of the field:

There are no easy answers. Herbert developing into more of an orchestrator, a coverage manipulator, should be outlawed. It’s unfair.

The Chargers are able to scheme open space and open windows without forcing a 4.3 receiver onto the field. The tight splits and the formations create natural leverage advantages, and Allen and Williams punish teams for it. There is an assembly line of long-limbed, savvy receivers who can bully one-on-one coverage or feast on option routes. That eliminates the need to put a true burner onto the field just to shift and morph the defensive coverage. There are few ‘alerts’. Everyone is live in the progression.

And here’s where the Chargers have truly inverted their structure. They have become a footballing oxymoron: They throw out of heavy sets; they run out of spread sets.

Rather than pack in tight to play some power football, they pack in to throw the ball. And rather than spreading receivers evenly across the formation to throw the ball into space, they spread-to-run, trying to lighten the box through the pre-snap formation — a spread-option principle run without the option portion:

It’s not overly complex, but it works.

The threat of switching that up hangs over everything, and it can discombobulate a defense

(And they do switch it up on a drive-to-drive basis. They run everything from everything!)

That’s another advantage of those condensed looks: The Chargers are able to keep extra blockers in (or not) without tipping their hand pre-snap. It’s tricky to Blitz The Formation, as defensive coaches like to say, or to blitz the tendency if it’s plausible that from any look Williams or Allen or whoever could stay in to block, could run a quick out, or could be selling the run hard before scooting downfield on a double-move.

That’s too many options. It’s too much to cover. And with it all happening in an instant right up on the line of scrimmage, there is little-to-no time to recover if you make a mistake or read it incorrectly.

The Chargers currently have a 73 percent pass success rate out of heavy personnel groupings this season, which is tied with Dallas for the top mark in the league. Like Dallas, they’ve been so-so running the ball out of those looks, averaging 4.4 yards per carry. But those dud plays help set up all of the things they’re able to do in the passing game. That’s a trade-off worth making.

It’s from those same pre-snap snapshots that they let Herbert do what he does best: Take shots down the field. With Allen and Williams as two of the premier one-on-one route runners in the league, they’re able to run the vintage Saints-Lombardi isolation designs:

But their most effective tactic is getting into big sets, keeping extra blockers in, and running two or three-man route combinations. With time and space, Herbert is able to sling it.

What are you even supposed to do? You have to play off-coverage to the field to respect the quick-game and the run-game. And as you’re towards that, here comes the play fake and a receiver buzzing past you on the deep over. Oof.

The Chargers have the potential to churn out and yards and to hit to explosive plays, from any and all personnel packages – the holy grail. And here’s the thing. Even if the Chargers aren’t running anything fancy. Even if you think you’ve got a fairly mundane look pretty well covered. Herbert can always go ahead and do this:

That’s just filthy. Utter filth. Some passes exist only because Herbert envisions them, and dares to throw them.

That stuff – the 40-yard opposite hash throw, on a rope, right into the Cover-2 hole stuff – is always on the minds of defensive coordinators. They — usually — want quarterbacks to take those throws; they’re low percentage throws, and that’s the best the defense can hope for in the modern game.

They’re not for Herbert. He hits deep shots at an unseemly rate. That’s his natural habitat, moving then launching; it’s how he clubbed teams over the head during his rookie year.

Last season, teams were (somewhat) happy to back up and play coverage against the Chargers. They were betting that they could overwhelm the offensive line, flush Herbert off-script and that the young quarterback would make just enough bad plays that they could absorb the other improvisational shots.

That didn’t really work, but Herbert’s issues within (a bad) structure added to a rough O-line meant that teams were able to win just enough early downs to make the thing a wash. Not this year.

The offensive line is good — at least it has been so far.

Lombardi deserves some credit there, too. Everything is clicking upfront, the condensed formations and general diversity of the offense have made things easier on everyone. Lombardi has even embraced the McVay tactic of using the jet/motion-man as a frontside blocker rather than as a piece of eye candy or coverage revealer.

It’s those subtleties that give a team and quarterback confidence in their play-caller.

Right now, Herber doesn’t have any holes in his game, and he’s able to toggle between personas on a down-to-down basis: Want him to play the Peyton Manning role and dance his why down the field? Sure thing. Want him to deliver a chunk play that rips a hole through the heart of the Dallas defense? That’s old hat by now. Herbert brings intricacy and nuance for the nerds and loud highlights for when you want to see an athlete do cool stuff. He still injects some needed chaos into the carefully crafted structure.

It’s telling that the comparisons have mostly stopped. When Justin Herbert came into the league, blessed with a ridiculous arm and capable of creating off-script magic, everyone rushed to find his analogue.

Aaron Rodgers was a popular choice. Comparisons with Carson Palmer – a supped-up, modernized version – made some sense. There were cap tips towards Mahomes, though rookie-year Herbert was more prototypical, lacking the kind of slingshot, whippy release that makes Mahomes, well, Mahomes.

Herbert has murdered that parlor game. Defenses don’t know or care what to make of him anymore. They are just terrified.

Lombardi has taken all that was right and good about the Drew Brees-era Saints and placed it in the hands of a 6-foot-6, power-throwing, nimble-enough anomaly. It’s similar to what Sean McVay is building with Matthew Stafford, only Herbert is ten years younger. How about we take some of the finest play designs and hand them to guys who can also chuck the ball 50-yards downfield on a rope? It took Stafford twelve seasons to find an ecosystem in which he could really thrive, the offense elevating his game rather than vice versa. Herbert has found schematic bliss in year two.

The Chargers are still figuring things out. They’ll trim some of the edges as the season progresses, dumping what doesn’t work and doubling down on what does.

Good luck to everyone once it all clicks.

If you enjoyed this piece, you can become a premium subscriber of The Read Optional to receive three pieces of content a week and access to the back catalogue.