Film Room Five: How concerned should we be about Matt Ryan?

Issues in Indianapolis; Baltimore muddying read-blitzes; running backs go sailing; more motion talk than you knew you needed

The Film Room Five is back! And we’re here to answer the biggest questions: Is it time to worry about Matt Ryan? What’s going on with the Bengals? How did Baltimore control Miami’s read-blitz packages? And should this piece have been sliced into five columns rather than one overinflated piece to preserve the sanity of my editors?

Let’s hop around the league.

1. Matty’s on thin ice (sorry)

This isn’t how it was supposed to go for Matt Ryan. Ryan was supposed to be the latest and final quarterback on the never-ending Colts conveyor belt of maybe-washed-maybe-bad quarterbacks. After years of snap-to-snap tumult, Ryan was supposed to provide some stasis.

It was a fair bet. Last year, Ryan still had “it”. He moved well in the pocket, slipping and sliding to avoid the rush. He still had oomph on his fastball, allowing him to squeeze the ball into the tightest of windows

Drop that player into a Frank Reich offense, with an overwhelming running game and a pair of creatures lining up at wide receiver, and stir. The AFC South title should have followed — comfortably.

It hasn’t been that way. Ryan was supposed to come in as the kind of field general that the Colts have lacked in the Reich era. Carson Wentz was too Carson Wentz-y to make ReichBall fully operational; Philip Rivers was shot by the time he paired up with the coach. Ryan was supposed to sit neatly in the middle ground.

Through two games, we’re closer to the Rivers way of things than with Wentz.

Now the caveats. The offensive line has been a mess. The run game has looked constipated — though they’re still the finest “wham” team in the league. Depth at wide receiver, which had a flashing warning sign heading into the season, has vanished within two weeks. Chris Ballard spent the bulk of the preseason piling on local reporters for daring to raise – obvious – questions about the team’s lack of depth at a primary position. Ballard snarled. The reporters were proven right.

During the Week 2 horror show in Jacksonville, the Colts' receivers struggled to gain any sort of separation. According to NFL Next Gen Stats, which uses the tracking data from the chips implanted in the players’ shoulder pads, the Colts’ targets averaged the least amount of separation of any pass-catching group in the league against the Jags. The league average is 2.91 yards – on any given snap, not just targets. Ashton Dulin averaged zero yards of separation (!); Dezmon Patmon 0.99 yards (!!); Mike Strachan 1.64 yards (!!!); Mo Alie-Cox 1.86 yards (!!!!).

That’s four targets with fewer than two yards of separation on average. All told, that group played 61 percent of the Colts' snaps – meaning that four of Ryan’s targets were blanketed on two-thirds of Ryan’s dropbacks. Kylen Grayson, the team’s move tight end, was the target most consistently open, finishing with 5.39 yards of average separation. He was targeted twice.

Ripping Michael Pittman Jr. and Alec Pierce out of the lineup vaporized the Indy passing game.

But that’s not to absolve Ryan of the blame. He made some mind-numbing decisions, pressed when he didn’t need to press, and showed impatience as his line crumbled around him. More jarringly: He looked old.

That is some deeply disturbing stuff. Look how little fizz there is on the ball.

Early in 2022, Ryan has looked like a shell of his former self. The Ryan that could still grip-it-and-rip-it in 2021 is missing. Last year, he was in the last vestiges of his window-throwing days, the point in time where a QB can drive a ball into the smallest of windows, even if his receivers haven’t created the needed separation or the play design fails. This version of Ryan is now a landmark thrower: The kind of quarterback who has to get the ball up and down early, tossing the ball to patches of grass (with a ton of loft) to compensate for his declining arm.

That’s a real “oh no” scenario for the Colts. It looked a year ago as if Ryan could squeeze another couple of years out of his arm at the highest level. It’s looking now like he only had a few months left.

This version of Ryan is a problem – perhaps not the problem but certainly a problem. Adding Ryan to the fold was supposed to elevate the area of the offense where Carson Wentz failed, most notably punishing defenses in the middle of the field. That’s harder to do as a landmark thrower, one who needs receivers moving into that space in order to get the ball up and down in time.

Playing that style of offense requires three things: Precision, perfection, and weapons. Having a big arm isn’t essential, but it certainly makes things easier. Miss by a click, and there’s plenty of time for a cover man to recover.

It can also take time for the scheme to spring open receivers to the intermediate and deeper levels of the field rather than have receivers flash open enough for a passer to drill the ball in – time that Ryan doesn’t have behind a shaky offensive line.

Indy traded for Ryan to help ameliorate areas of the offense that failed under Wentz, and to extract as much out of Pittman and Pierce as possible – two giants on the outside who do some of their best work attacking the middle of the field. His becoming a landmark thrower changes that calculus.

The duo’s size remains an advantage; they will increase the margin for error for the quarterback even if they’re blanketed. But Ryan entering the Rivers/Roethlisberger I’m-lobbing-grenades mode compromises a lot of what the Colts' offense is intended to be.

Reich’s offense is about crafting layups for the quarterback thanks to quick exchanges at the line of scrimmage, RPOs, and basic sight adjustments based on the leverage of the defense. It’s intended to be a ball-out-now offense with carefully crafted shot plays deployed at the right time.

Reich was forced into adjusting some of that when Philip Rivers was at the helm. Everything became more horizontal, with the coach building in some slower-developing concepts that gave his receivers time to get out in the pattern and break toward daylight before the ball dropped from the heavens and they could go create after the catch.

It was all a little too staccato compared to what the Reich offense can be when it’s really rolling. Ryan was supposed to be the panacea: The Rivers-esque quarterback who could operate the offense as a professional and who had enough arm talent to take advantage of the throwing windows that Carson Wentz refused to accept – without the downside that he could throw up all over himself on any given drive.

Ryan heading more towards the late-career-Rivers part of the continuum is more than a fleeting concern. Reich and his staff will be forced to adjust – and will be doing so without depth in the receiving room and an offensive line that has been brutalized in pass-pro for two straight weeks.

Those aren’t fun problems to have. For fourteen years, Ryan has been a solution, not a problem. That has tipped in the opening two weeks. What should have been a last hoorah for the long-underrated quarterback is looking like it’s going to be a slog.

It’s a long season. It will be trying to watch the Reich-Ryan axis try to troubleshoot their issues on the fly.

2. Running backs are going sailing

Getting running backs vertical out of the backfield is nothing new, but it’s never been more prominent. As defenses shift to the two-deep world, coaches are finding increasingly creative ways to try to puncture those two-deep shells with a fifth-eligible releasing out of the backfield.

The Sail route makes sense. A perimeter receiver can back up the coverage, drag one of the half-field safeties closer toward the middle of the field, or press even more vertically to clear out a space underneath for a running back to go rolling into.

Previously, against single-high coverages, running backs had been releasing with more verticality. Coaches across the league embraced a form of four-verts, with the running back flying upfield as the fourth vertical route and slipping into the space to one side of that single-deep safety as that safety’s eyes were occupied by the other vertical route to the opposite side.

Getting to that look through creative means became a challenge all its own. And it’s the same thing with the freshly embraced Sail route.

Andy Reid has long been the archbishop of letting his running backs go sailing. One nifty concoction flows from the Chiefs’ split-back sets, with the sailor releasing as the second back out into the pattern. In the split backfield, one running back (or receiver or h-back) goes flying out first before the back on the sail route releases out late. It’s a nice inversion, with the defense triggering as though the second man out will sit down as the team’s checkdown.

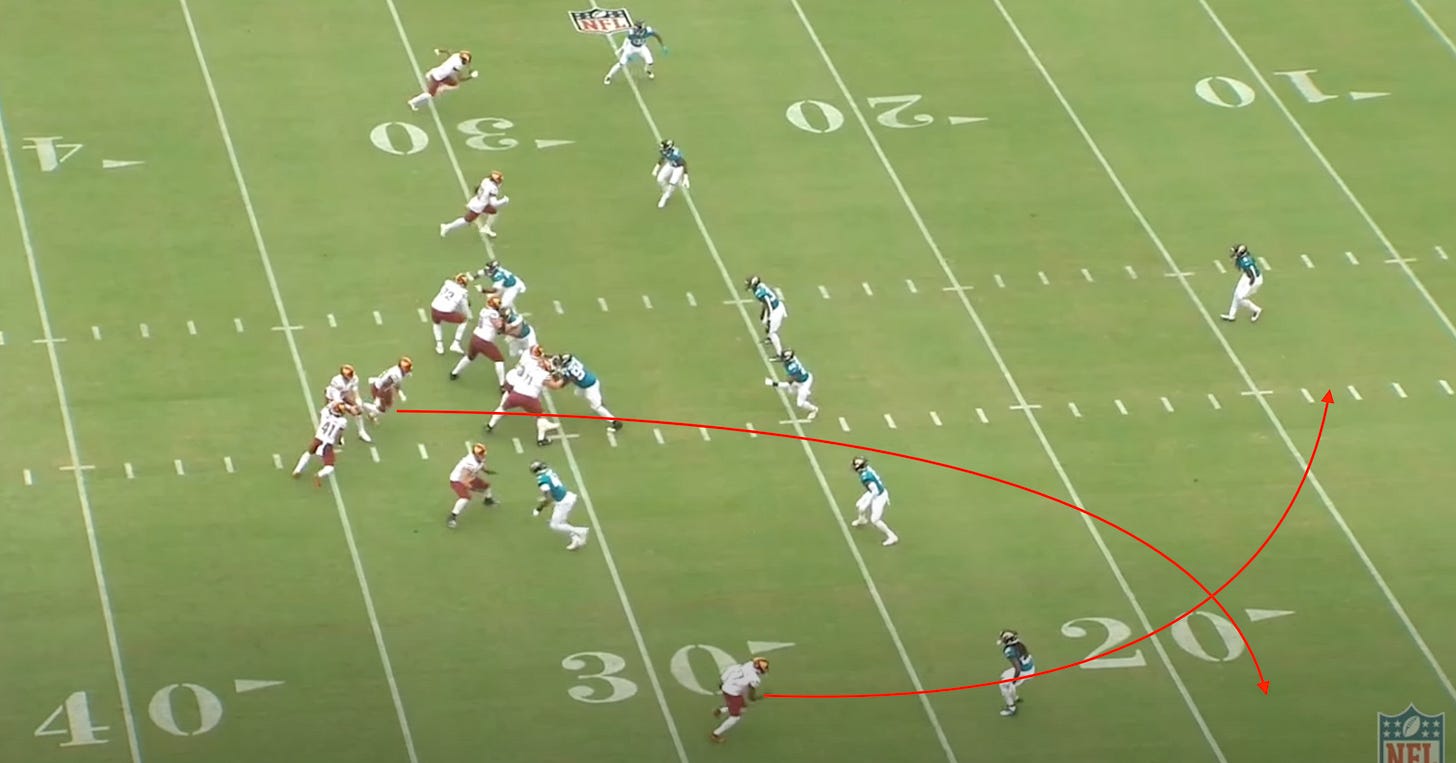

Reid is not alone. Coaches across the league are finding increasingly creative ways to feature backs on Sail concepts. Here’s one doozy from Washington OC Scott Turner:

I’m telling you: Turner is good at this, man. Not content with crafting one of the most interesting run games in the league, Turner is now having a party in the passing game with more playmakers at his disposal. In week 1, he dialed up this soon-to-be classic.

There are a bunch of moving parts here. It’s a split backfield, and so the Jags toggle to a generic cover-three look. On the back end, it reads like a drift concept for the Jacksonville secondary: The isolated receiver is running a deep post; the ‘X’ receiver is running a dig. But there are a whole bunch of other moving parts in front of that.

Turner is attacking the intermediate portion of the field to the weak side with a sailing running back from the front side. At the snap, the back takes off, flying through a gap vacated by the right guard and right tackle. The backside receiver attacks vertically before pressing towards the post, looking to occupy the corner and middle-of-the-field safety. He’s aiming for the hashmark. The corner is looking to the sideline, climbing over the top of a dropping linebacker and in front of the corner.

It works. The safety sits in the middle of the field, reading the quarterback and checking for the post. As the receiver makes his break, the corner goes flying with him, leaving a void underneath for the running back to waltz into.

For Carson Wentz, it’s pitch and catch stuff – an easy explosive to an uncovered receiver. Happy days.

But that’s not all! Check out what’s happening closer to the line of scrimmage. Turner builds in a secondary, late-developing concept in case access to the Sail route is cut off or the dig is unavailable (it is! This Washington group is fun!).

There’s a delayed mesh concept at work between the second back in the backfield and the #2, slot receiver to the field side – it’s not a true mesh concept, but it’s at least mesh-curious. Both use stuttered releases: The slot is strolling off the line of scrimmage, aware of the timing of the concept. He doesn’t want to get out in the pattern too early. The back who took the play fake from Wentz has two assignments: he first scans for any protection responsibility before bursting through the line and aiming for the area left vacant by the dig route.

The timing is ideal. If the post is robbed, the sail compromised and the dig closed off, there’s a neat two-way crosser in the middle of the field, designed to pick off one of the linebackers occupying that space and to get both targets on the move running into the area that has been cleared out by the two vertical releases from the perimeter receivers.

Talk about giving your brain-fart-prone quarterback options! Everything is distributed evenly. There are chances for explosives and layups. The timing of the two concepts flows seamlessly, not forcing a hazard-prone QB to speed up his clock. That’s good offense. Seven points to Gryffindor.

Quality OCs will continue to find ways to spring backs open downfield from the backfield – likely with options based on the structure of the secondary. Keep your eye on what Turner is doing with the Commies.

3. Motion-Motion-Motion

It has become a consistent bugaboo of mine that a whole bunch of the football commentariat points to a team's motion/shift figures as a one-size-fits-all situation. If you motion a bunch, that’s “smart”. If your team ranks near the top of the motion standings, your coach is automatically placed in the “innovative” and “not dumb” camps. Slip to the bottom, and you’re liable to be ostracized from the football-watching world.

Rarely is the follow-up asked: What is a team trying to do with motion, particularly in the run game? If motion alone were a sign of craft, imagination or success, they would be removing Vince’s name from the Lombardi trophy as we speak and applying Matt Canada’s.

They are not.

There is an epidemic in the league at the moment of motioning for motion’s sake. Canada stands out as the most garish example, but it’s been just as much of an issue for Mike LaFleur and the Jets as anyone else. Teams mostly use motion in the run game to try to mess with the math in the box: some are looking to clear a body out; others looking to overload the point of attack – or to at least get the ideal leverage possible for the target point of the concept.

The top coaches switch this up on a concept-to-concept basis, with clear tendency breakers when needed. As detailed in the preseason, the Patriots have changed up how they relate motion to their from-the-gun, one-back power concept (which they returned to Week 2 vs. the Steelers after the slogfest vs. the Dolphins) – they shifted from motioning away from the target to help clear out the box to motioning towards the target to try to bring extra guys to the party.

It was a subtle change. The results are as yet to be determined, but theory of it, with this roster, is slightly lacking. It’s been similar for the Jets. They’ve mostly used motion in a way that looks to mimic what Matt LaFleur and the Packers do with their outside-zone scheme, looking to overwhelm the point of attack with a late-moving motion man – typically a jet-motion runner converting into a blocker with the ideal in-out leverage.

But given the investment in the offensive line, the talent they have up front (even with injuries), and the clear advantage they now have at the receiver spots, it’s fair to wonder why Mike LaFleur is so insistent on bringing extra hats into the equation. It’s not playing to the strength of the team – it’s picking a philosophy over deploying the correct tactical response to a specific situation with the specific skills of a roster.

Motion alone can quickly become inconsequential to the run game if it isn’t part of a more holistic approach: Who is the motion man, and what is the knock-on impact of that to a defense; where are you aiming for?; what’s the concept?; Where is the motion starting from?; what are the rules of the defense vs. the different kinds of motion in their different front structures?; do you have a variety of motions?; is a motion tied to a concept or is it a grab bag?; does the defense respect the motion?

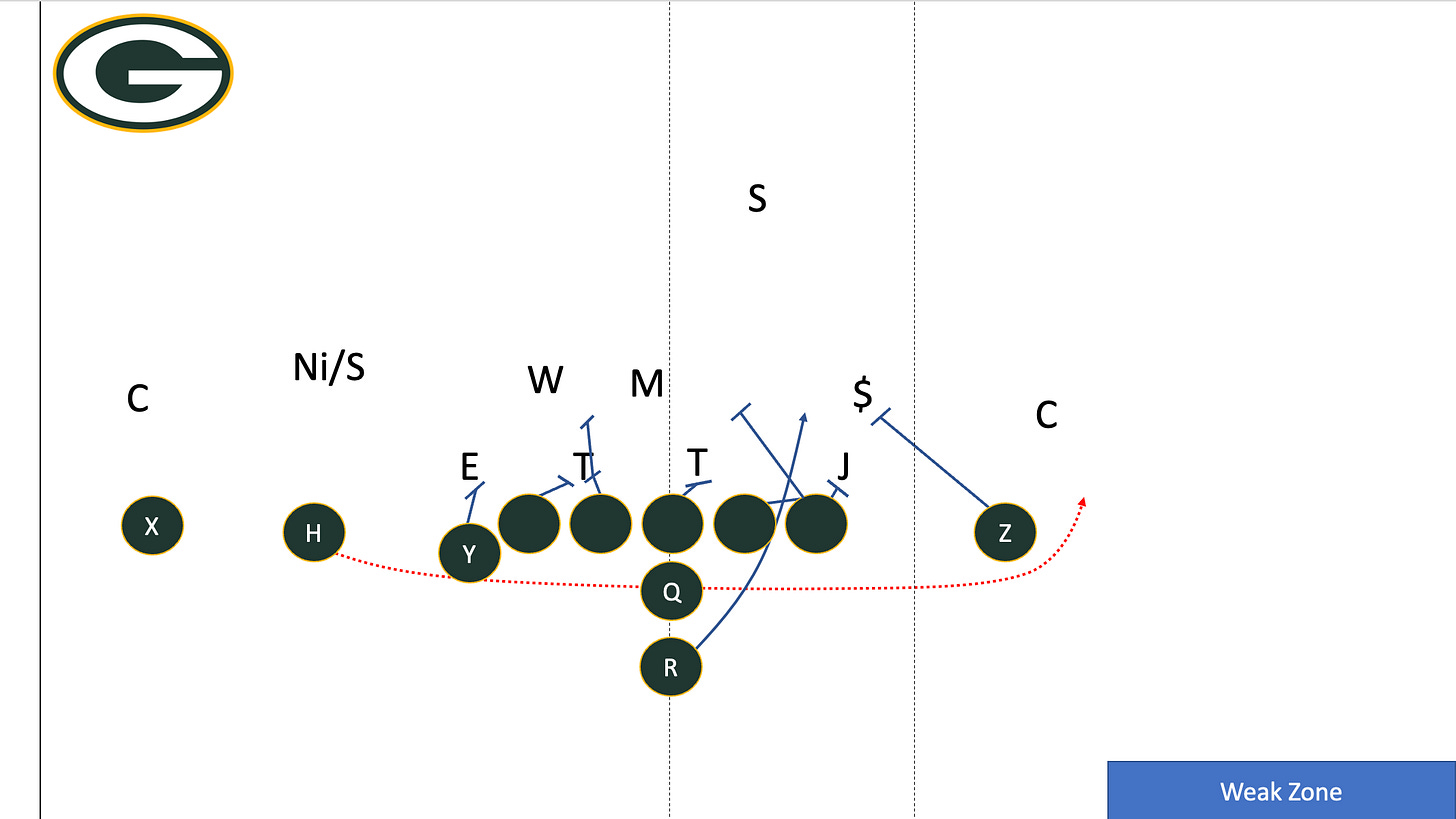

The Packers are the top motion team in the league. There is purpose behind everything they do. Take their weakside zone package. The point of a pre-snap jet motion is not to bring more hats to the party, but to widen the alignment of the perimeter defenders against congested formations; to extend things horizontally slightly so that they can puncture the defense vertically.

If the motion-man can force the defense to bump across, it gives better leverage for all three blockers who are trying to spring the target point: The receiver, guard and tackle. The motion man isn’t there to clean out the boundary corner; he’s there to bring the down safety closer to the receiver and to (hopefully) elongate the alignment of the end man on the line of scrimmage.

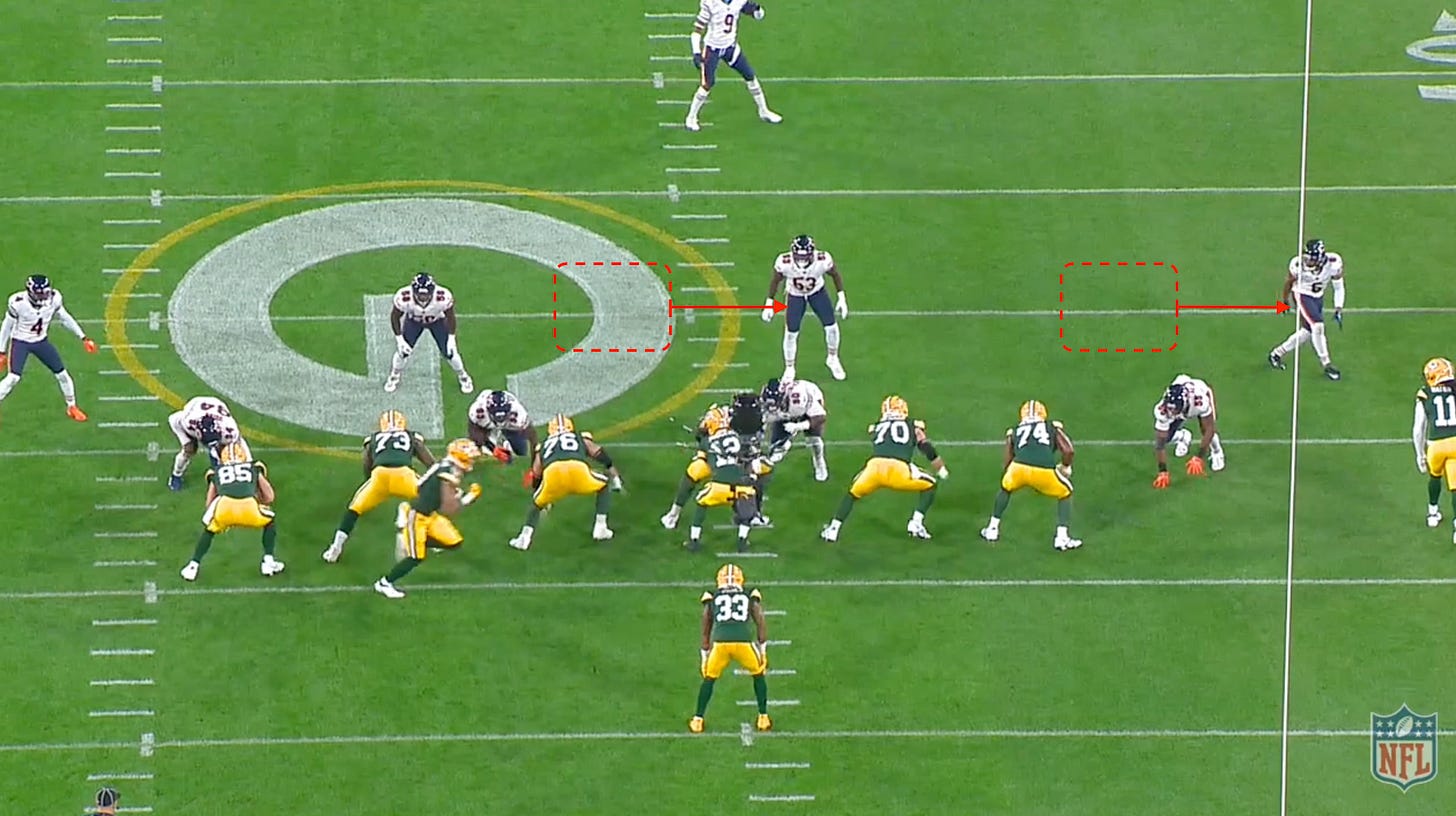

Here’s an example from the Bears game:

Pre-snap, Chicago is in its base look: there are two off-ball backers to the strong side of the formation and a down safety covering the B-Gap bubble – the area between the right guard and right tackle.

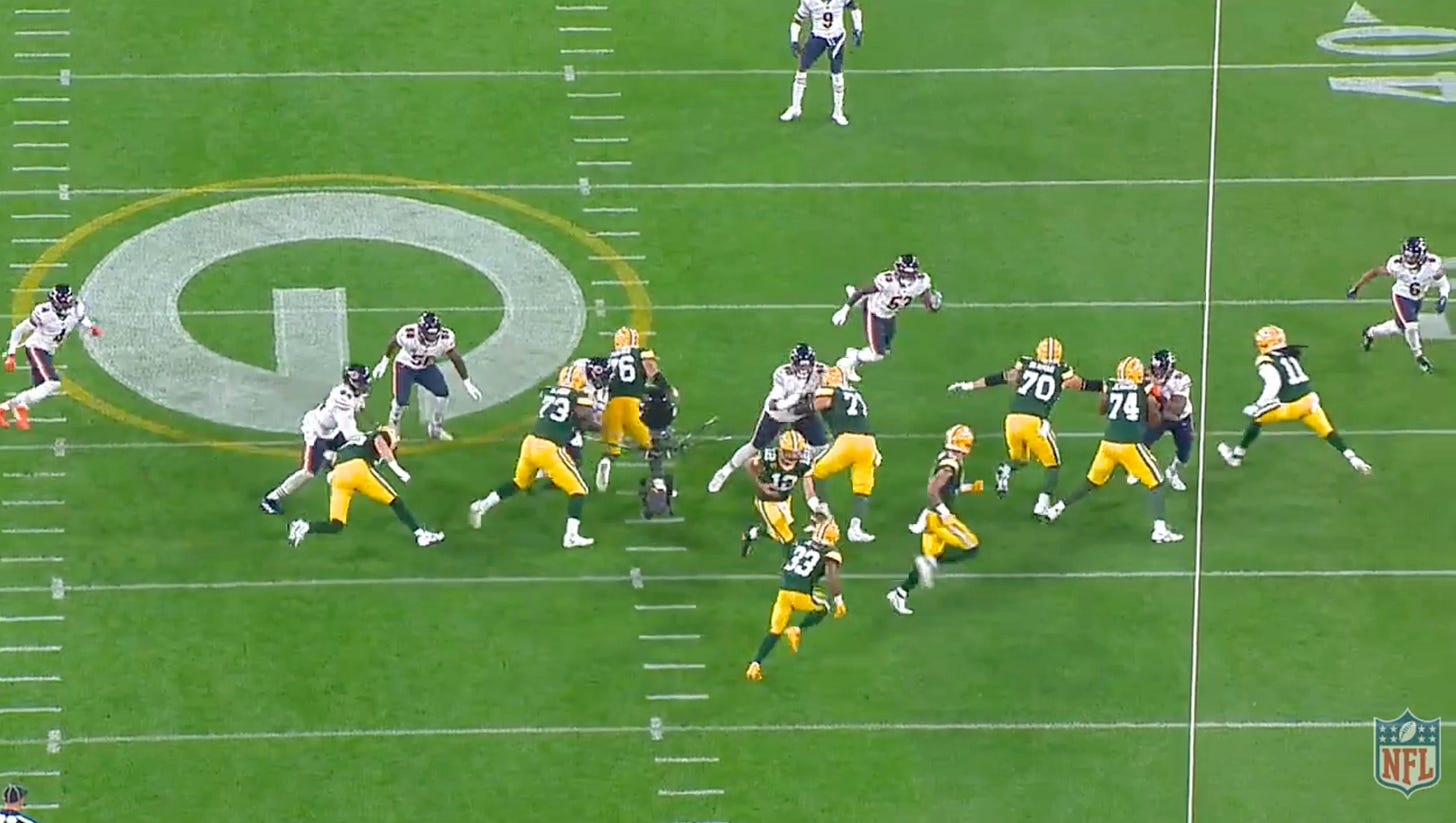

As the motion man sets off, the defense rolls with him.

That does two things: It compresses the space between the frontside blockers and would-be tacklers and it allows more time for the back side to clear out a cutback lane. In the words of one world-weary traveler: Great success!

At the snap, this thing should POP. Center Josh Meyers gets an excellent hinge block on the Bears’ nose tackle, opening up a huge lane. The receiver is able to climb up to dig out the safety. There is a tidy angle for guard Royce Newman to check on the EMOL before pivoting to the Mike linebacker.

The motion was so effective that it dragged the down safety all the way out of the box, allowing the receiver to work from the safety onto the Mike. But he’s not needed! Newman is already up there sealing the second level.

That left the receiver in no man’s land. By bailing on the safety, he’s forced to cut across the formation to find someone. Had he stuck in his spot, he could have cleared out a clean lane all the way up to the corner some twelve yards downfield.

But the thing still has a chance to hit on the back side. With the cutback lane sealed, Jones can dance out of the back door. The issue: The back side cut blocks. The initial step is good: The Packers get body presence on the Bears’ three-tech (in the corridor beside the left guard) that gives right tackle Elgton Jenkins the time needed to cross the tackle’s face.

Jenkins is just unable to stick the block. Justin Jones, the Bears three-tech, is able to slip off the block and wrap up Jones from the back side before he’s able to shoot through the cutback lane.

The design worked. The motion man did his job. What was a blocking mechanics letdown could have been an explosive run.

It’s a flawed example – every team now runs some version of weak-zone with a motion flashing across the LOS. But it illustrates the overriding message: there is a clear point to the motion, and the defense responded as intended. And the Packers have a playbook full of different styles of motions (slingshot; orbit; fast) to achieve the same basic result without revealing a tendency.

As we progress through the season, try to track what a team is doing with motion and why they’re doing it (and whether or not it’s paying off), rather than focusing on whether they are motioning or not.

4. The Motion Redux

Thought we were done with the motion spiel? Wrong.

Motion in the passing game is different from motion in the run game. Teams use motion with the pass primarily for two reasons: To gather intelligence (to discern the coverage or rotation) or to disrupt. As hybrid coverages and locked coverages have become the norm, the former is less of an advantage than back in the good ‘ol days.

The former, however, remains essential. In the traditional sense, that second point means to move someone across the formation to gain a leverage advantage on a specific player or to force the defense into communicating, which can lead to subsequent miscommunication.

Against the Dolphins, the Ravens charted a third path. They motioned to mess with the ‘Phins wonky read-blitz concepts.

You probably remember the Dolphins torturing Lamar Jackson with the blitz last season. They brought heat to Jackson on 60 percent of the quarterback’s dropbacks, and dialed up a bunch of zone pressures on the other 40 percent. Jackson was under duress all evening and struggled, completing 5-of-13 on throws when he was pressured, with a costly pick to boot.

Brian Flores left Miami in the offseason, but new head coach Mike McDaniel kept Dolphins DC Josh Byer at his post. On Sunday, Byer once again tried to bring all the heat to Jackson. Once again, he used Flores’ patented read-blitz approach – balancing between true “blitzes”, read-blitzes and zone pressures. They pressured Jackson on 55 percent of his dropbacks.

(A read-blitz is as it sounds: The defensive front reads the protection of the offensive line at the snap before the potential blitzers decide if they’re a part of the pressure or dropping out into coverage.)

It didn’t work. Jackson roasted the ‘Phins any time they sent an extra man or two, finishing 13-of-16 (81.3%) vs. the blitz for 213 yards and two touchdowns. That’s an average of 13.3 yards per attempt.

Not great, Bob.

Jackson elevated his game – he also wasn’t working with a broken receiving corps or o-line, which helped. He was quicker on the trigger. He was decisive. He was accurate. But coordinator Greg Roman (who would later lose his mind down the stretch of the game) also helped out.

The idea of the read-blitz is to overwhelm the LOS by crowding it with seven (or six) bodies covering all of the gaps – some mugged, some not – and having one offensive lineman block a ghost, springing a free rusher elsewhere. One or two blockers engage with someone they think is coming (who starts to engage and then bounces out) while they leave the static defender on the perimeter who looks like he’s dropping before he attacks the backfield with an open alley.

Miami often takes its “read” cues from the edges, so Roman decided to mess with the typical picture. He used motion to flash a body across the formation at the snap, dirtying the read for the would-be blitzer on the end of the line.

The motion man could convert to an insert blocker, picking up a free runner inside. He could clean out the EMOL, someone who started to blitz thinking they had a free lane before being crunched from the side. He could be window dressing, sowing the seeds of indecision into a front that’s asked to play read-and-react football.

The Dolphins front was too often paralyzed by uncertainty – should I stay or should I go? Is he motioning to release into the flat or to pick me up? Is he inserting inside or clipping the edge?

Adding an extra (unforeseen) blocker into the equation helped even out the numbers for the offense. Where the Dolphins thought they had gamed up a seven-on-six or six-on-five, it was truly a five-on-five; may the best players win. What should have been clean lanes were closed. Droppers were left in no man’s land, the ball flying over their heads before Jackson could take an extra beat.

Jackson had time and room to operate – and he punished the defense for it.

Roman made costly mistakes down the stretch (moving from a style that had worked to an empty-focused setup that was too predictable), but his smart approach to warping the Dolphins’ blitz looks helped cover up an area the Dolphins exploited last season.

Other coaches will take note. It will be interesting to see if Ken Dorsey and his staff carry some of Roman’s tactics into Sunday – the Dolphins blitzed Josh Allen on 65 percent (yes, really) of his dropbacks last season.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Read Optional to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.