Yes, it's time to be concerned about Justin Fields

Chicago's coaches don't trust their young quarterback; Fields doesn't trust his coaches

There are moments when you just know a quarterback gets it. When he’s thinking one or two steps ahead; when he’s instigating rather than reacting; when he’s navigating the offense with the confidence of a five-year vet.

Let’s call them the lightbulb moments. Sometimes, they’re tough to articulate, one of those know-it-when-you-see-it things. It might be the quarterback resetting a protection before ripping the ball to his hot read to beat a blitz. It might be holding that backside safety for an extra split second, in order to deliver a strike over the middle of the field. Or it could be a quarterback canceling the hitch portion of his dropback, altering the timing of the play, knowing that extra tick might mean the trapping corner can squeeze down on an out route. The scheme demands one thing; he knows the game requires something different.

Then there’s the opposite. Let’s call them the oh-nos. You know the kind – Jets fans are treated to around twenty a year. They’re the moments where everything still seems a beat too fast for a quarterback who’s played double-digit games; when the quarterback misses the descending backside linebacker as he works from one side of the field to the other; when he misses the hot throw in favor of bailing out of the pocket to create all by himself; when chaos remains the defining theme of a game that requires some sort of structure.

A few oh-no moments in the rookie year are to be expected. Push that into a quarterback’s second year, though, and you start to get itchy. Stack multiple oh-no games on top of one another to open your sophomore campaign and you run perilously close to run-on-the-bank territory.

And so it is with sincere regret that I must inform you that the bank accounts on Justin Fields Island have been drained. Property prices have bottomed out. The IMF is working up a stern letter.

Week four serves as a league-wide pivot point. By the near-quarter mark of the year, teams know who they are. All those fancy offseason designs that looked good on the whiteboard but suck on the field? They’re out. Those crafty concepts that work in theory but not with this specific personnel, they’re for the chop.

Playbooks shrink. Teams start to major in certain concepts. The foundation becomes clear, with week-to-week tweaks depending on the opponent.

Week four might not show us exactly what a team really is. But it shows us who they’re intending to be. The Bears have shown us they’re a side that does not trust their quarterback, and Fields has given us little reason to prove why they should.

Look away now, Bears fans – if you haven’t already.

So far, it’s been grim viewing in Chicago. In a general sense, it’s clear what the Bears want to be on offense: A run-heavy team that takes play-action shots down the field. New Bears OC Luke Getsy has installed a creative, diverse running game, one that blends some of the league’s greatest hits with some certifiably frisky one-off designs.

Getsy, the former Packers passing game coordinator, hasn’t quite been as Machiavellian as Matt LaFleur (he also doesn’t have Aaron Rodgers or Davante Adams to work with) in the run game, but every week there’s a new brick pasted on top of the run game that builds on one laid the week before. Right now, the Bears have one of the top early-down run games in the NFL. They rank 5th in EPA per play and 17th in success rate when running the ball on early downs. That’s a pretty good profile for a team that spent the offseason indulging in some organizational self-sabotage by stripping an already weak offensive line down to its bones – and who are relying on the league’s weakest crop of receivers to pose a semblance of a threat in the passing game.

Defenses know Chicago wants to pummel them with the run – and the Bears have been successful pummeling them anyway. One gold star to Getsy and co.

It’s the opposite, however, in the passing game. The Bears have been bland and predictable, static and formulaic. There’s none of the down-to-down creativity the team has shown in the run game, It’s a long way from the richly layered approach Getsy helped build in Green Bay.

The numbers are galling. The Bears currently rank dead last in early-down dropback success rate. In fact, they’re the only passing game in the league to fall below the 30 percent threshold on early downs… which is… concerning. They have the fewest number of explosive plays of any attack in the NFL – and they’re the only group not to break double digits.

What gives? There are dozens of variables:

Elongated routes that don’t match the timing of the concept.

Poor blocking mechanics.

Protection issues whenever the defensive front moves (which is either the fault of the quarterback, center or both).

Somewhere in the region of nine thousand boot-action plays per game, with little variance on the individual designs. Defenses rarely even respect the fake because they’re not concerned about being beaten by the receiving corps.

Isolated routes that demand receivers win one-on-one on the perimeter.

A receiving corps that’s incapable of winning one-on-one on the perimeter.

A quarterback who all too often misses the easy stuff.

A quarterback who barfs up ugly turnovers.

I could go on. My head is spinning from typing all this out. Sloppy mistakes have undercut everything; no passing attack in the league so consistently shoots itself in the foot – through design, spacing, a lack of talent, protection breakdowns, and, notably, issues at quarterback.

In short: It’s been turgid. Not being talented enough is one thing; dawdling on routes, playing out of sync with the timing of a concept, and failing to correctly set protections is another. Building a complete roster is hard for any capped-out team. But building a culture that values fundamentals, and the drudgery of sharpening habits, shouldn’t be. The Bears’ passing game is failing at both.

Coming into the season, it was easy to inculpate Chicago’s front office. The criticism was fair. It felt, from the outset, like the new staff– those upstairs and in the coaches’ offices – had little faith in Justin Fields. That they were looking to kick the can down the road to the next offseason, happy to spend this year stumbling along while they addressed their cap sheet before hitting the reset button in the summer of 2023.

To any objective viewer, that seemed true – this is a team that intended to anchor its passing attack around Cole Kmet. And that is largely how it has played out: The Bears lack the juice on offense to get anything rolling through the air. But three things can be true at once: The Bears do not have enough talent on offense; the design of the passing game is blah; Justin Fields is playing poorly.

That last point is often lost in the shuffle as we get into wider-ranging discussions about how the Bears have knee-capped their own quarterback by surrounding him with an ill-equipped roster. How come the Dolphins and Eagles have invested so much in strengthening around Tua Tagovailoa and Jalen Hurts to see if they’re “the guys” while the Bears have handed Fields a bag of beans and asked him to create magic?

It’s a valid discussion. But let’s park it for today. Because even with that point taken, those constraints understood and accepted, Justin Fields has been poor through four weeks. And we’re tipping slowly from struggling-but-explainable to utterly perplexing.

Fields currently ranks 31st among eligible quarterbacks in RBSDM’s EPA + Completion Percentage Over Expectation composite.

(Stats folks like to make these things sound complex, but when you break it down into its component parts, it’s easy to understand. Stick with me.)

EPA+CPOE is about as close as you can get, statistically, to calculating how valuable a quarterback is to his team. It doesn’t use raw output to measure a quarterback’s success. It pairs nerdy metrics with the NFL’s Next Gen data – the chips in the pads of players – to spit out a composite score. It’s measuring both the value of the play and how much the quarterback impacted that play above what would be expected based on historical baselines. By that standard, Fields ranks ahead only of Baker Mayfield, who looks as though he’s actively trying to force the Panthers to secede from the league.

Strip away the nerdy metrics and think about this: Fields has piloted his offense to 20 points vs. an okay-ish Texans defense and 12 points against a solid Giants group.

In year two, that’s not close to good enough. Pointing fingers at the general architecture of the offense– the frustrating spacing; the lack of an early-down passing game; the inability to separate early in the rep – is a credible defense. But, at some point, Fields has to, you know, show something.

The biggest issue: Trust. Field’s signature trait at Ohio State was driving the ball down the field. He was decisive. He understood the nuances of the deep passing game. He didn’t bob and weave in the pocket, looking to extend then create out of structure. He played on time and in rhythm, ripping defenses apart with a bombs away approach that was soaked in sheer delight. I cannot wait to get rid of this ball ASAP because I know my guys are going to be open. Everything he did, he did fast.

Fields could play in the second phase, but that wasn’t his intent. He wanted to see it and rip it. And see it and rip it he did. The idealized version of Fields at the pro level was not a backfield phantom in the mold of Russell Wilson but a down-the-field playmaker closer to Matthew Stafford on the quarterback continuum.

Driving the ball deep down the field is not a skill that thrives in only precarious and rare ecosystems. It should unlock a whole lot for any offense, even in a time of retreating defenses and deeper defensive shells. That the Bears cannot find more creative ways to get to their shot menu is a failure of coaching, not Fields.

Still: The quarterback doesn’t do himself a ton of favors. This is a human game, after all. Trust goes a long way. And it rolls two ways: A quarterback trusting the scheme and his coaching staff; the coaching staff trusting their quarterback.

Rip through any of the Bears opening four games and the lack of trust between Fields and his staff leaps off the screen. There’s a hesitancy to everything Fields is doing. He doesn’t want to pull the trigger. He doesn’t trust what he’s seeing, or doesn’t trust that the solution his staff has devised for a specific problem is the right one. He’s living for the second phase – and shying away from opportunities to let fly early in the rep and early in the down and distance, grinding the passing game to a halt.

Fields has often looked paralyzed by fretful indecision – both in the operational elements of the offense and when deciding to throw the ball. In an offense working to muster anything it can through the air with a humdrum crop of receivers, that’s crippling.

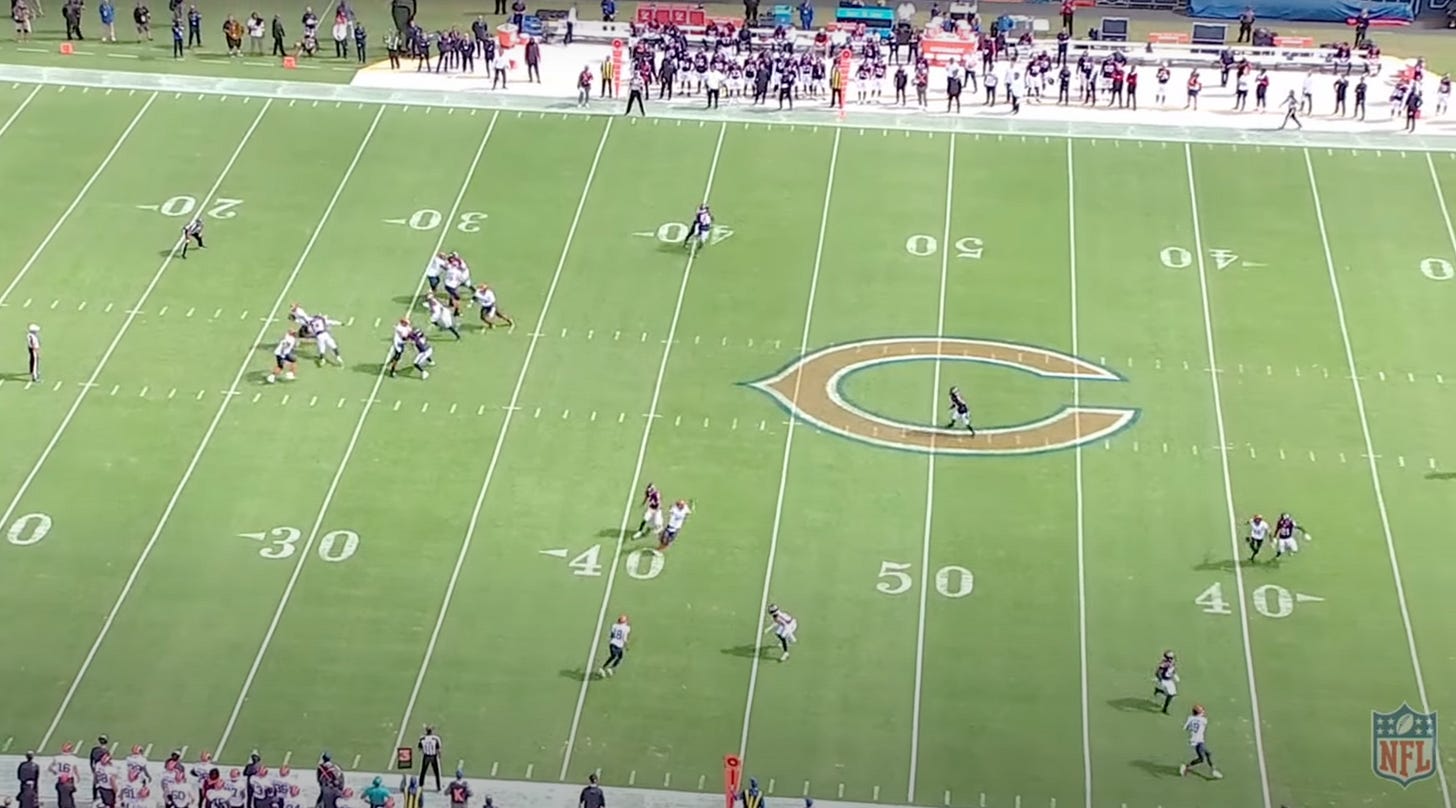

I mean, look at this:

Focus on the process, not the result. It’s first and ten. The Bears are in 4x1, empty (QUADS!!!) – with some funky spacing (a pseudo/elongated bunch with a boundary receiver out in a plus-plus split, pressed right up along the sideline). It’s Getsy giving his quarterback a chance to play in attack mode from the outset of a drive. The coach is daring the zone-tastic Texans to play man coverage. And if not, to reveal their hand to his quarterback so that Fields can attack downfield at the snap.

It’s a smash concept, nothing fancy, with double chips, and a pivot route serving as some underneath eye candy for the boundary corner. The play is designed to secure a hi-low to the field so that the quarterback can take a shot. If the boundary corner sags off, he can hit the twirl and get on with the game; if that corner bites down, there’s an ocean of space behind to hit the corner.

At the snap, the Texans invert things, sliding into a one-cross look. Fields has two jobs: To read that boundary corner and make a quick decision while also holding the middle-of-the-field safety.

The Bears get what they want: the boundary corner sags; the nickel is flat-footed, leaving room for the #2 receiver on the corner to skip into. Either is open for Fields, on time and within the flow of the concept.

Go on! Rip it!

He doesn’t. Instead, Fields hitches. He’s unsure what to do. The anticipation throw is there, 20-plus yards down the field. But as he waits, the space closes. Underneath, he has the pivot route wide open with a chance to make a break for the sticks.

Fields opts for neither. He holds the ball… and holds the ball… and holds it some more. He holds it long enough that a three-man Texans rush is able to get home, forcing him to make a move in the backfield to evade pressure in his face.

Fields made the would-be tackler miss and scampered downfield for a big gain with his legs. The outcome was sound, the process awful. Fields froze at the top of his drop, unable or unwilling to sling the ball with touch and anticipation to a receiver along the sideline for an easy (by NFL standards) explosive.

It’s become a recurring theme. Fields seems allergic to throwing the corner route – a must as teams move to an increasing number of two-deep, or two-become-one, defensive coverages, and a staple of the LaFleur-Getsy-Rodgers offense.

*Rubs temples*...Where to begin? This is a rough one. The Bears are once again jumping into empty and asking Fields to play the role of point guard – this time in a 3x2 set. The Giants are confused; they can’t figure out what personnel to get on the field or who should be aligned where. For Fields, it’s a pick a side concept: Either he works the two side or he works the three.

Notice anything? To the trips side, the Giants have three players turned away from the line of scrimmage or communicating with one another at the snap. They’re unsure of where they’re supposed to be or what they’re running. Kayvon Thibodeux, premier edge rusher, is stuck over by the numbers, aligned as the nickel, palms pointing up to the sideline. Where the bleep am I supposed to be? What is going on?

Fields’ eyes are fixed on Thibodeaux.

A palms-up defender typically means one thing for a quarterback: Attack.

Fields does not. He instead looks to work to the two-man side, where the Bears are looking to run a pick to spring a slant route. The Giants play three over two to the boundary, dropping an edge defender into Fields’ throwing window and cutting off the quick supply line.

Fields works back to the trips side. What does he have? The same snapshot as before: you have a corner on the perimeter in a hi-low bind, a corner route jetting behind and an underneath receiver sitting on the sticks. If that DB drives down, Fields has the corner in space. If that DB sinks back, the underneath route has a chance to gather the ball with all sorts of green ahead of him to go make a play.

Again, he bails the pocket, squeezing both of the routes into the sideline and bringing more defenders to the party.

He’s forced to try to fit the ball into a tight window as pressure arrives. The throw is incomplete. What should have been a 20-plus yarder turned into a no gainer. From first-and-ten at midfield to third-and-six versus a defense with the wonkiest blitz menu in the league – and another three and out. Oops.

It’s not often you get a double oh-no moment on one play. Failing to attack the miscommunication and misalignment of the defense was one mark on the board. Failing to deliver to either the corner route or the underneath route after missing the miscommunication and bouncing back to that side of the field is bordering on oh-no-squared. You don’t need Alan Turing to tell you that’s not great.

This kind of stuff drives cantankerous, old-school, stick-to-the-freakin-scheme coaches insane. Working all week to apex a corner only to have a quarterback – one who wants to throw the ball down the field – mothball the design is enough to send even the most cerebral coach the way of Ken Dorsey.

It gets back to trust. Fields is working with the most pedestrian receiving corps in the league. And while there are shots where guys are schemed open, there’s a whole bunch of ISO-ball where players are being stung with plaster coverage all over the field. Take a shot every time all five eligible are covered at the top of Fields’ drop and by the end of the first quarter you’ll be more incoherent than a Netflix rom-com.

Fields has become almost an oxymoronic player. He’s a downfield gunner who’s leery of releasing the ball downfield. Last year, he was asked to play with the world crashing down around him. That’s not so this year, even as the staff coaches as though it’s afraid of its own roster.

Defenses have been happy to sit in match quarters for prolonged stretches. The point of a match quarters defense is to bracket the easiest throws (routes by the slot) and force the offense to throw the toughest throws (fades and comebacks). That’s where Fields should make his hay. He was at his best in college at driving the ball down the field outside the numbers. Yet in the pros, he’s been gun-shy.

We still get to see flashes of the old cowboy and, man, is it sweet:

Look at that thing! The arc, the precision. Still: There’s a hiccup in his thinking. Should I? Shouldn’t I?

At Ohio State, Fields operated at warp speed. In the pros, he’s working in slow-mo. Fields’ average time to throw currently ranks fourth in the NFL. He’s averaging three and a half seconds on his dropbacks. Some of that is skewed by his ability to extend plays, but a good portion of it is a hiccup in Fields’ release. Even when he can see it – he can sense it – that the ball needs to be out now – today; let’s go – there’s a pause, an almost audible “Am I sure?”

That’s the right decision. It’s a schemed-up shot: A heavy play-action dig – with the back (correctly) aborting the play-action to help out with a protection breakdown. It’s easy work. The linebackers are sucked up, the dig hits behind. You see this play forty times a weekend. You know the timing from your sofa: Hit the back foot, get the ball out.

As soon as Fields hits the top of his drop, the ball needs to be on its way, fizzing towards the receiver. The ball should hit the receiver in the face as soon as he starts to break, giving him a chance to go attack some grass after the catch.

Fields delays. He waits. For what, who knows? He squeezes in a couple of bounces, just to make sure the picture he is seeing is correct. By the time he’s ready to release the ball, the receiver is planted, facing back towards the line of scrimmage and waiting for the ball right by the hash.

By the time the ball arrives, a pair of defenders are able to corral the receiver before he can do any further damage after the catch.

Those extra beats have been consistent, and they’ve proven costly. A lot of his passes are a hair off -- too low for galoots, or a bit behind them or way out in front:

Oof. There we have Fields vs. Lovie Smith and the Texans defense. You don’t need to be Ernie Adams to know you’re going to see a steady diet of Tampa-2 vs. Lovie. Getsy calls for a variation of “989” to try to puncture the Tampa shell: A pair of go routes to the outside (that can break to the corner depending on the leverage of the corners) in order to occupy the two corners with a post looking to puncture in between. The Texans have a linebacker working as the middle hole defender, who’s responsible for matching anything vertical in the middle of the field, matched up (and behind) a wide receiver. Bingo!

By scheme, it should be another chunk play. But Fields dithers. He gathers himself, pauses, and then lets loose, overshooting his target by seven or eight yards into the waiting hands of a defender.

At the NFL level, those are shots that you just cannot miss – all the more so if your game is predicated on driving the ball vertically. At this point, the late balls and back-breaking turnovers are piling up.

Fields can’t help himself. In the vertical game, everything needs to be snappier and quicker. He looks like a player who’s unsure of where he’s supposed to go with the ball, and who has little to no trust in the people around him. He looks, understandably, like a player suffering from a crisis of confidence.

On top of the big misses and the mind-numbing interceptions, there are the little things: Fields continues to miss on the easy wins.

The whole point of planting Fields in a wide-zone-then-boot offense, of booting him at a league-high rate, is for that right there. It’s to get him onto the perimeter with space, so that he can make a man miss and create offense by himself, or to flip an easy throw to an open target, on the move, so that the target can rack up some YAC.

The component parts of what makes Justin Fields JUSTIN FIELDS are still there, but everything is discombobulated at the moment. There’s no snap-to-snap consistency. There’s confusion and timidity – two words never associated with Fields in college.

A good chunk of the blame should rightly fall on the Bears organization, for their handling of his rookie year and the moves (or lack of them) over the offseason. But Fields must shoulder a portion of the responsibility, too. His game has been erratic, his decision making worrisome. Sure, there are few bells and whistles to the Bears passing game, but there are still plenty of shots for Fields to take advantage of. He needs to kick his addiction to second-phase creativity and play within the rhythm of the scheme. Only then will the Bears staff shuffle more opportunities onto his plate.

Chicago currently has the lowest early-down passing rate in the NFL. Only 28 percent of the first-down offense is subsumed by Fields and the passing game. The league average is 58 percent. The 31st-ranked team in the league, the Giants, currently sit at 35 percent, which seems downright lewd by the standards of the buttoned-up Bears. Last season, the bottom rate in the league was 42 percent, some 14 points higher than the Bears. No team dating back to 2003 has ever dropped below the 30 percent threshold, let alone into the high 20s.

Cooper Kupp (42) currently has as many receptions as Fields has completions (42).

If week four is the point at which teams trim the fat and show you who they want to be, the Bears seem pretty adamant: They want to hide their quarterback. And when you see the efficiency numbers on the ground and Fields’ misfires and misreads through the air, it kind of, sort of makes sense for a coaching staff that didn’t have a hand in drafting Fields.

Still: I remain a stead-fast Fielders believer. Feel free to paddle away from the Island, Wilson and I will be here until the end – well, maybe not Wilson.

Fields has all the physical tools and there have been just enough flashes to keep even the strongest skeptic Fields-curious. But it’s go time. Even as the staff tries to reign him in, there are throws there to be made – throws that Fields hit in college; throws that any starter in the league should hit; throws the Fields is thus far refusing to even attempt.

The ideal scenario here is an Expandables-style extraction. Let’s call Arnie, Statham, and Sylvester and get Fields to a staff with a true vertical passing game and a professional receiving corps (or else embrace my current legislation that would see Bruce Arians function as a roving pass game installer).

But that’s probably one for the offseason. In the here and now, Fields needs to play better. He needs to trust the scheme. He has to be more decisive – and make better decisions. Then, we can pile on the Bears for not doing more — in terms of personnel and play-calling — to help their young quarterback.