Mike Macdonald is having fun

The Ravens DC was a question mark heading into the new season. What did we learn in week one?

A quick note: Apologies for the lateness of this first column of the week. I’m currently dealing with a family issue which meant I got this to my editor late. We will return to our regularly scheduled programming next week.

And if you haven’t yet, sign up to The Read Optional Discord channel to chat away with the community during the weekend’s games.

One of the key subplots heading into the season was what the Ravens’ defense would look like under new DC Mike Macdonald.

Replacing Wink Martindale – now the DC with the Giants – is tricky. Martindale is one of the most idiosyncratic play callers in football; he is a high priest of the “inverting the downs” movement. He lives, at all times, in attack mode. In a league that’s fearful of blitzing quarterbacks – because they’re so bleeping good vs. the blitz – Martindale shrugs his shoulders and deals up even more heat.

Things fell apart for Wink’s group last season. Injuries left a talent void. They failed at the basics: they struggled to line up; they struggled to communicate and adjust vs. motion and movement; they struggled to pick up switch releases, the bedrock of the modern NFL offense. It took the return of Josh Bynes at linebacker – a two-down thumper – to bring a measure of normality – to, you know, ensure everyone was lined up and in the right position prior to the snap.

It was a mess. No defense conceded more throws of 20 yards or more in 2021 (74) than the Ravens; they finished 30th in the league in explosive play rate.

Baltimore opted to move on from Martindale in the offseason. John Harbaugh turned to Macdonald, who had previously worked on the Ravens’ staff before spending a year-long apprenticeship as the DC in Michigan with Harbaugh’s brother.

At Michigan, Macdonald’s defense was fairly rudimentary. He had two of the five best pass rushers in the country – and he acted accordingly. Macdonald did some crafty things on the back end (mostly vs. the tidal wave of RPOs we see in college football but that are less prevalent in the pros), but up front, he was able to rely on a relentless pass rush to get home with just four guys. Macdonald’s defense, structured around individual gameplans rather than a singular ‘philosophy’, fueled Michigan's playoff charge, leading Harbaugh to call him up to the bigs.

Keeping things within the family was sensible. There was no need to switch up the verbiage or make wholesale changes. Still, the question remained: Would Macdonald keep some of Martindale’s bonkers blitz designs and pressure-heavy tendencies or revert to the style he ran at Michigan that called on his players to line up in a simplistic structure and out-execute the offense?

Through one game, the answer appears to be somewhere in the middle. Six things stood out from Macdonald’s first game:

Things were tighter and more coordinated on the back end – Who knew? Having talented, healthy players can help a football team! (losing Kyle Fuller to an ACL tear will hurt).

The Ravens were able to pressure effectively with four.

Adding Marcus Williams and Kyle Hamilton in the offseason has allowed Macdonald to redefine who the Ravens are at the second level – they’re able to run a ton of three-safety sets, with Chuck Clark lining up as a dime linebacker and Hamilton moving here, there and everywhere.

They have speed, length and athleticism at all three levels, which allows them to be more versatile than in recent years.

Macdonald kept some of Martindale’s most creative designer pressures, though slightly altered.

He made subtle switches to how the Ravens bring four (or five) rushers.

Let’s hit on the latter two points today because they feel more significant than a one-game fluke. Martindale was a serial gambler. He liked to crowd the line of scrimmage with as many bodies as possible. He wanted things to feel tight and congested. He wanted the opposing quarterback to be wondering, at all times, who was coming and from where. By compressing the width between the players up on the LOS, any blown blocking assignment would hit quicker than pressuring from depth or out from the perimeter.

Martindale paired those narrower fronts with a ton of “read” blitzes and overload rushes – the kind Brian Flores popularized in Miami. The goal was to force the offensive line to set its protection based on the pre-snap formation of the defense, get them to pick wrong, and then have a pass rusher or two come screaming home before the line could realize it had made a mistake. He was as likely to send six as he was to bounce a couple of guys out.

It was a boom or bust style, particularly on money downs. For years, it boomed. With injuries and a lack of depth, in 2021, it busted – and cost him his job.

Macdonald used a similar strategy vs. the Jets in Week One with subtle differences. Macdonald widened the defensive front. On third downs, Macdonald mimicked the Niners’ style of using a split front with one or two muggers (linebackers or safeties walked down into one of the gaps along the front) to help dictate the protection of the offensive line. Understand what the protection scheme is, and you’re better able to penetrate it.

Martindale used wide-9s and elongated fronts – almost all coaches do – but he preferred to get to that setup by overloading one side of the formation with traffic and planting the wide-9 far away from the rest of the formation on the opposite side of the field, known in the Baltimore system as a “Boss” front.

Even in his wider fronts, Martindale wanted to keep a down lineman inside head-up over the center.

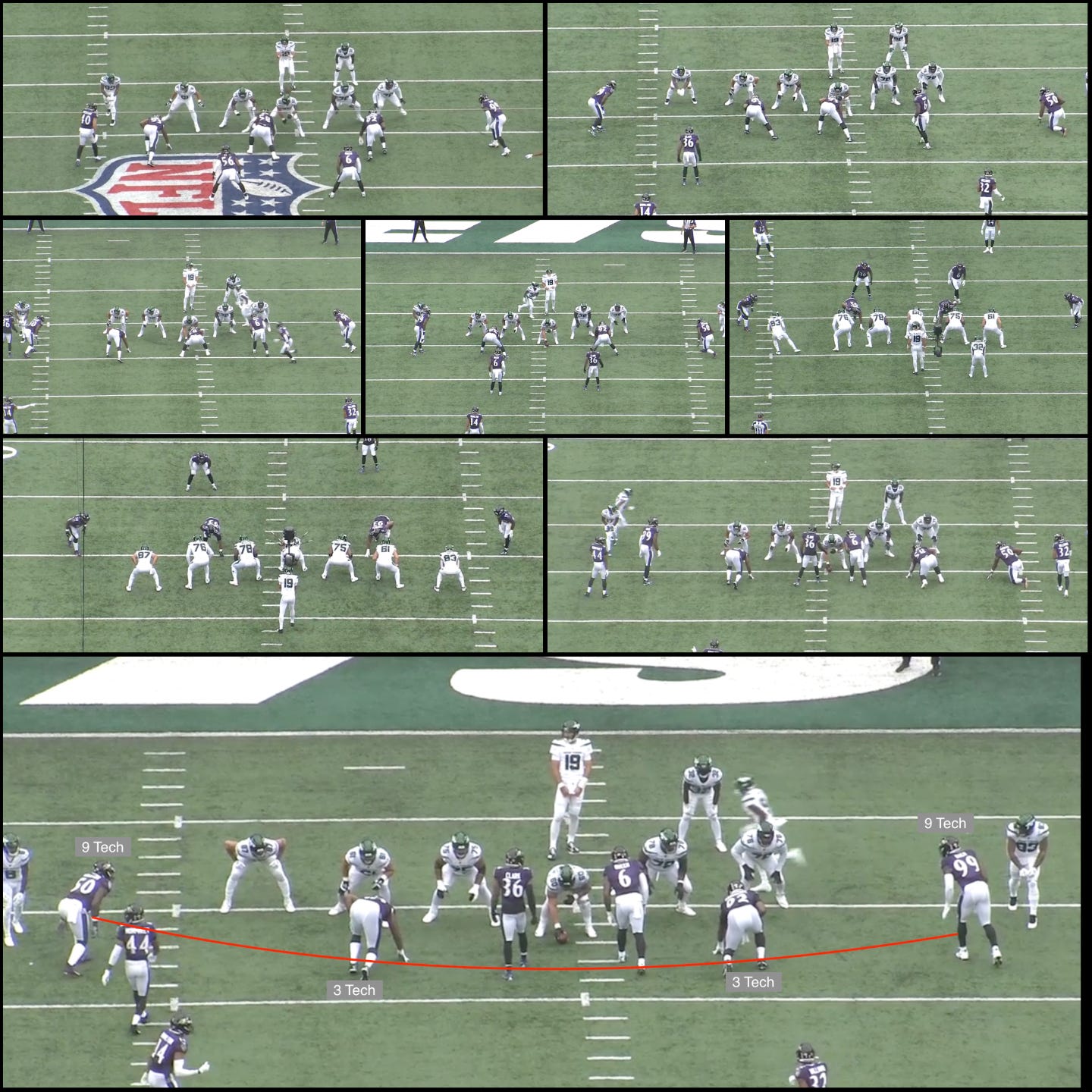

Macdonald instead stretched out the entire front – shifting the interior defenders down a gap and pushing the edge defenders farther out.

A split front is as it sounds: The front is carved in two, with two three-techniques outside the shoulders of either guard and two wide-nine techniques. Split fronts have been around forever, and have been championed by the likes of Jim Schwartz and Wade Phillips. Using an exaggerated split – as Phillips did in Denver and Macdonald did on Sunday – makes it tough for the offensive line to double anyone. There’s just too much ground to cover; even with a pair of wings in to chip, the Ravens edge defenders were stealing as much width as possible.

Rather than compress the front, Macdonald widened it as much as possible, making it tough for the Jets to double anyone and upping the impact of stunts and twists – the key to the stunt game is to get linemen onto as many different levels as possible so that they pick one another and spring a pass rusher free; widening the front naturally throws off the timing of the collisions (all four players do not impact at once), making it easier to plant the offensive line onto different levels. It also makes it easier for the DC to drop the edge defenders out into coverage if they’re running a zone pressure.

Tacking on a mugger or two does a few things: it helps dictate the protection of the offensive line; it allows the defense to run “read” blitzes in the middle of the line scrimmage (decide who is blitzing based on the blocking scheme), and have them hit quickly; it blurs the vision of the interior linemen as the pass rushers start to twist and swoop; it forces the o-linemen to read then scan rather than instinctively leaping to the best spot to seal off a potential looper.

Macdonald made another subtle tweak: Run back through those earlier snapshots. Did you catch it? All the defenders – interior and on the edge – are in tilted alignments, facing inward towards the ball. By twisting the angle, Macdonald is able to more naturally scheme up a “crunch” rush rather than having his edge rushers dip-and-rip and run the arc towards the quarterback. And it provides a better angle for the pass rushers to run their gap exchanges (stunts and twists) without tipping their hand pre-snap by moving from a head-up alignment to more of a tilted stance.

It worked. The Ravens D-line turned the line of scrimmage into a demolition derby. The Jets failed to convert any third downs until midway through the third quarter, at which point they were bailed out by an illegal contact penalty (and Joe Flacco absorbed another massive shot). The Ravens’ front feasted. Justin Houston finished with six total pressures, showing there’s plenty of bounce still in his legs. Odafe Oweh showed signs of growth in his second season, finishing with five pressures. Justin Madubuike dominated the interior, racking up five pressures and a sack. All told, the Ravens front totted up 32 total pressures and four sacks.

Most importantly, they did so without sending a steady diet of heat. Baltimore blitzed on 27 percent of Joe Flacco’s dropbacks, an average mark. When the Ravens blitzed Flacco, the quarterback ate it up. When they rushed four – be it an organic rush or a zone pressure – he struggled.

There is noise in those figures: As the Jets chased the game and asked Flacco to drop back… then drop back… then drop back some more…the Ravens sagged off, relying on their front to clobber the Jets’ offensive line (they did) and sinking increasingly into zone coverage. In desperation mode, the Jets helped inflate some of those non-blitz figures.

Macdonald did a tidy job of balancing his four-man rushes with five-man pressures. And it’s in balancing those two worlds that he can best tap into the potential of this defense – the talent up front, the speed at linebacker and a remodeled secondary.

In that zone-pressure world, Macdonald dug all the way into Martindale’s bag of tricks. Martindale’s wackadoo designs are crack for football nerds. And Macdonald was happy to keep some of the more extreme “safe”pressures (typically a five-man rush with three-deep, three-underneath zone coverage behind) left over from his time working alongside Wink.

Yes! You saw that right! What we have there, folks, is a three-deep, three-underneath, fire-zone blitz. It’s straightforward in its description, but look at all the moving parts:

I mean, come on now.

Pre-snap, the Ravens are showing pressure. It’s another elongated front with eight – count them: eight – defenders up on the line of scrimmage. Marcus Williams, the league’s top middle-of-the-field safety, is walked down as the end man on the line of scrimmage to one side of the formation. Kyle Hamilton, the team’s move piece, is lined up 15 yards off the ball in centerfield.

Inside, there’s a pair of mugged linebackers. And over the top of the slot receiver is an extra body, weakside ‘backer Malik Harrison, who shuffles into a crouch to indicate he’s locking into man-to-man coverage with the slot.

At the snap, the Ravens rotate: Williams darts from his slot as the EMOL into the deep middle third of the field! Kyle Hamilton rolls into the weak hook zone. Odafe Oweh drops into a mid-hook. Harrison attacks the backfield. One of the mugged linebackers drops out; the other enters attack mode.

Flacco’s instinct is to get the ball out hot, to “replace the blitzer” and chuck it over the head of Harrison to the uncovered slot receiver.

Nope. That’s right into Hamilton’s zone, with Oweh offering an in-out bracket. Flacco is forced to hold the ball, to bounce around to try to make a play before he’s hit. The design – say it with me – adds extra beats to the quarterback's drop back, the beats needed for the pressure to get home. One rusher flashes in Flacco’s face before Patrick Queen comes screaming around the corner to try to finish the proceedings.

Flacco completed the ball and Garrett Wilson made a play after the catch, but the Ravens still got off the field on third down. And we’re interested, at this stage of the season, in the process more than the results anyway.

It was a vintage five-man pressure, albeit one with some quirky rotations – and it discombobulated a veteran quarterback who’s seen everything. It was also a design ripped straight from the Martindale playbook:

The mechanics of that pressure are different – it’s a four-deep, two-under fire-zone, and the perimeter blitz is hitting from more depth (which is partly why the pass is completed). But the general flavor is the same, and the influence is obvious.

That wasn’t Macdonald’s only tasty treat, either. Look at this doozy:

You saw that right. That’s just nose tackle Michael Pierce and friendly giant Calais Campbell dropping into middle hooks. But they’re not just dropping for dropping's sake. Track their eyes. Campbell is scanning to check if there’s anything quick and in-breaking to his side; Pierce goes hunting for the #3 receiver, his responsibility.

Again, there’s breadth to the front pre-snap. Again, there are mugged linebackers, establishing the protection rules for the offense. Again, the Ravens take advantage with a crafty design, two rushers flying free into the backfield – one picked up by the back, the other forcing Flacco to get the ball out hot.

Again, the Ravens got off the field on third down.

The early returns for this Baltimore defense were encouraging. The defensive front dominated the line of scrimmage in the run game. There was a nice blend of creative fire-zones and a tweaked four-man plan to get after the quarterback on passing downs. Behind that, the Ravens rolled out the kind of twitch and size at the second level that makes Jay Bilas’ heart flutter. How Macdonald continues to roll out his three-safety sets – and how he incorporates Patrick Queen, a souped-up safety lining up at linebacker, into the equation – is a tidbit to continue to monitor (things could be about to become all sorts of frisky).

We will know more in the coming weeks. It’s one thing to do it versus a statuesque Joe Flacco and a rusty Jets offense, though, and another to do it against Josh Allen and the Bills in a fortnight or Joe Burrow and company the week after that. And that’s a task made all the harder as the voodoo dolls have once again struck the Ravens secondary: Marcus Peters is out; Brandon Stephens is currently not practicing.

Some teams spend the early part of the season working themselves out of a fog. Not the Ravens. Mike Macdonald is out there having fun.