Keys to the game: Niners-Cowboys

One of the benefits of having a season where a bunch of teams are much of a muchness: A stacked wildcard slate.

Cowboys-Niners stands out as the game of the weekend. Here are a couple of key points to keep track of throughout the game.

Can the Cowboys block the Niners?

The Niners have the deepest, most ferocious defensive front in the league. And if it’s not the Niners group, it might just be the syndicate lining up on the other side of the field. But whereas Dallas generates a bulk of its pressure using five-man pressures – adding an extra linebacker to the rush and playing man-coverage behind – the Niners get home with just four.

We can be playing football until the end of the time and still the most impactful way to win playoff games will be to generate pressure with four rushers. You know the score: It allows you to keep extra defenders in coverage. You can get extra eyes on the ball. You can double team (and run more sophisticated cone coverages) on the opposing offenses’ most dangerous players. In short, pressuring with four opens up everything; it gives the DC his full menu and disrupts the rhythm and timing of the opposing quarterback and his offense.

Nobody is rolling out pass-rushers quite like Niners DC Demeco Ryans and defensive line coach Kris Kocurek. The group legitimately runs eight (!) deep. They lineup in straight-forward packages: Everyone in a sprinter stance from first down until third down. They play the pass first. They shoot upfield. They attack. They disrupt quarterbacks.

There is not a more disruptive group in the league. We’ll get to the passing stuff, but they’re just as impressive (if not more so) vs. the run. They get penetration, and they’re able to funnel runners to a clinical linebacking corps and the finest run-stuffing cornerback room in the league.

That’s no small thing. The Niners corners embrace contact. Ryans’ scheme and the initial surge of the defensive front are often granting the corners open tackles vs. the run. But the corners finish. And they finish with physicality. That matters. Since Week 10, the Niners have the best EPA per play vs. the run in the league, a testament to all the talent up front and the way Ryans has schemed up openings for his corners to attack the ball unblocked. Win those rushing downs, and it allows the front-four to do what they do best: tee-off on the quarterback.

Stopping the run from an even front with four strung-out linemen – two wide nine defenders’ way outside the tackles; two interior defenders, be it with a shade nose tackle or a split-front featuring two three-techs – is no mean feat. It takes the collective, and outstanding individual players who can make superhuman plays at an average player rate.

The Niners stick to their base no matter how compressed the offensive formation. Two tight ends bunched on the line of scrimmage? No problem. Bringing in extra linemen to attack with a jumbo package? Whatever. A condensed set with everyone packed around the box? We run what we run.

Opposing offenses will look to mash those sprinter-stance fronts with the run-game, trying to slam it down the Niners’ throat. Teams will ditch some of their more sophisticated run-game designs and settle instead for all of the classics.

The Cowboys run as diverse a run-game as anywhere in the league, mixing and matching concepts based on which back is in the game, the defensive formation, and the opponents’ tendencies. They can bounce to anything. Still, at root, they like to hammer fools with the staples: Inside-zone, Duo, and wide-zone.

One concept the Niners will use to try rebuff all of the Cowboys’ core designs is an insert pressure. Because they base out of an even front, the Niners look to get to five bodies up on the line of scrimmage post-snap by attacking the line with one of their off-ball linebackers. In essence, they’re trying to get to a ‘Bear’ front (a five-man front) after the snap – and all of the benefits that come with that – rather than aligning in it pre-snap:

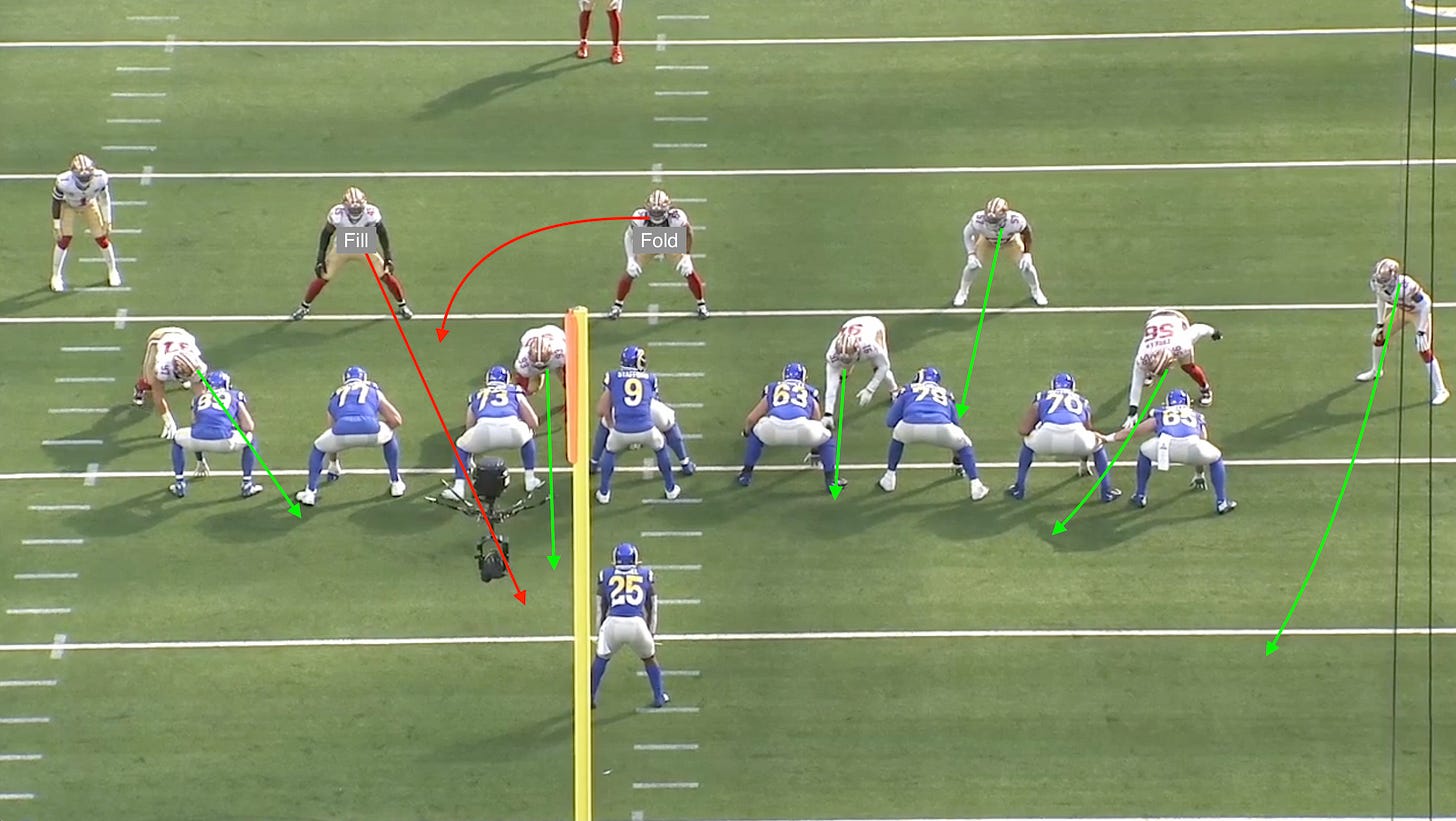

To maintain the sturcture, the Niners use a principle known as ‘fill and fold’. One linebacker fills — driving at the line of scrimmage and attacking his gap at the snap. Behind him, a linebacker folds around, looking to clean up any mess coming his way. The first linebacker wave should (in theory) create some disruption, forcing the running back to chop his feet or to look for a cutback. By then, the second wave of defenders – the fold linebacker, a safety, whoever – can wrap around to mop up:

One linebacker goes; the other replaces him. Neither might make the play, but by adding in a pair of layers to one side of the line of scrimmage, there are enough bodies to force the ball-carrier to look elsewhere, which can free up someone from the backside to scurry across to finish the play. Two flashes of color, that’s all the defense is looking for:

Dallas is happy to play pin-and-pull football. But they’ll also back their meaty offensive line to drive the 49ers front off the ball. To try to even it out, Ryans will look to get a linebacker downhill early to re-direct the back – the Niners send the linebacker opposite Fred Warner and let Warner, a one-man cleaning crew, act as the second wave.

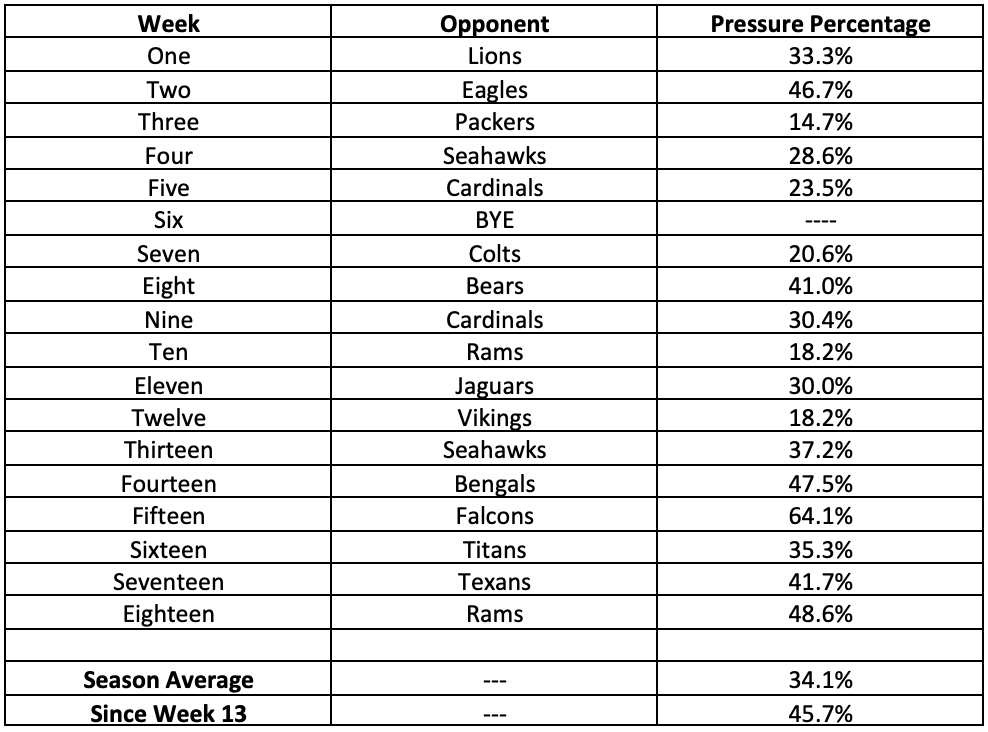

The run-game is one thing. Blocking this Niners group in pass protection is something different entirely. For the season, the Niners have a 34.1% pressure rate. Meaning: They pressure opposing quarterbacks on over a third of their dropbacks, which, if you’re keeping score, is really bleeping good. Even more impressive: Since Week 13 the Niners have pressured opposing quarterbacks on 45.7% of their dropbacks on average — ON AVERAGE!

That’s not a typo. San Francisco is generating pressure on almost half of quarterback dropbacks. That’s not one game. It’s not against a single, overwhelmed offensive line. It’s consistent. Over that span, the group’s lowest pressure rate for an individual game was 35.3% -- a figure that’s still above their season average. The highest over that span: A ridiculous 64.1%.

Yeesh. I get nervous thinking about that sat behind my desk with a nice ham and cheese ciabatta. Can you imagine stepping in front of that thing? Facing this Niners front is the NFL’s equivalent to a game of chicken. You’re going to get hit by something at some point; how often and with what force? Who knows? Best of luck.

Demeco Ryans’ third-down pressure packages are really, really impressive. The Niners don’t run a whole lot, but what they do run they run at the highest level. It’s quality over quantity.

In obvious pass-rushing situations, with the elongated front — those wide 9’s and interior rushers — the Niners use an organic rush. It’s typically four defenders running the traditional trappings; the stunts and twists that you see being run up and down the country. There’s nothing overly fancy, just good players executing classic concepts at the highest of levels.

In fact, early in the season Ryans upped the Niners blitz rate. Robert Salah, the team’s former DC, ran basic drop coverages with a four-man rush utilizing the prototypical stunts and twists. When Ryans first jumped into the DC chair, he sent more creative looks, tagging extra rushers into the pressure. During the first nine weeks of the season, the Niners averaged 8.6 blitzes a game, per Pro Football Focus. That represented a blitz rate of 31 percent.

The issue: The group stunk. Injuries (and inexperience) meant that Ryans was forced to send extra bodies to try to manufacture a rush. But that left a wonky secondary exposed. The Niners were picked apart. After nine weeks, they ranked 23rd in the league in EPA per play.

Then, the defense got healthy. Then, Ryans was able to re-shape things. He was able to rush with four. He was able to reduce the team’s blitz rate, freeing up extra defenders to help protect a shaky cornerback room in coverage. From Week 10 onwards, the blitz rate dropped to 15 percent. On average, the Niners sent just 5.7 blitzes a game from Week 10 onwards.

Liftoff. From 23rd in EPA per play, the Niners shot all the way up to 7th in EPA per play by season’s end.

Rolling out a steady trove of one-man people destroyers helps. The Niners’ rush plan and coverage are now in perfect sync. And in Nick Bosa, Arik Armstead, DJ Jones, and Arden Key they have four dominant pass-rushers – not to mention the likes of Charles Omenihu, Samson Ebukman, and Jordan Willis who will all cycle in, all bringing some oomph. In Bosa and Key, the Niners have two of the top-five players in the NFL in Brandon Thorn’s True Sack Rate. No other team comes close to having two in the top-five in High-Quality sacks.

This is a front that functions on players, not plays. But Ryans has added some overloaded fronts to try to create extra havoc.

Overloads are as they sound: The defense allocates more rushers to one side of the formation than the other. They run a topsy-turvey front: three down linemen (sometimes more) to one side with a solo lineman to the other.

Ryans likes to isolate Nick Bosa — his best pass-rusher — as the player opposite the loaded side of the formation. From there, the fun begins. Fred Warner (the Niners’ best and most versatile player) will align next to Bosa, mugging one of the interior gaps. That puts the o-line in a bind: do they slide away from the Niners’ most dangerous rusher or commit resources to the side away from the overload? It’s tough. The Niners having oh-so-many high-level pass-rushers makes it a damn near impossible question.

Below, the Rams have seven potential protectors in the box. In the front, the Niners have five. The Rams should have the Numbers and resources to block it up. They opt to man-block the thing, each offensive linemen accounting for one of the five players in the defensive front, the tight end chipping on Bosa and then releasing, the back looking for work, and then flying into the flat.

Game over. You can almost see the Niners’ players licking their lips.

The Niners ran a basic stunt. The nose tackle cross-faced, aiming to shoot across the face of the center and into the hip of the right guard. Fred Warner, aligned inside the tackle, first stabbed towards the guard and then worked out around the right tackle. Bosa drove inside, looking to drag the right tackle with him and to barrel through the right guard, hoping. The goal of the defensive front: To get the right side of the offensive line (center to right tackle) onto different levels. To distort the wall. To have the Rams players pick one another as they tried to fight through the carnage, opening up a free alley for Warner, the looper, to swoop around.

That’s a bingo.

It’s simple. It’s effective. Ryans used a formational quirk to get favorable matchups in pass protection – the flavor can change week-to-week depending on the opponents and the lineman (or linemen) he wants to isolate. Then he trusted his All-Pro players to do All-Pro things. The result: Carnage.

The Cowboys have one of the league’s best offensive lines. They are as adept as any unit (when healthy) at exchanging stunts and twists, but there’s nothing a group can do when they check to 5-0 protections and they’re blocking man-to-man no matter where their man goes.

The Niners don’t run a diverse set of pressure paths because they don’t need to. But Ryans continues to find subtle ways to tweak things week-to-week to create pressure with four and to draw-up sacks when he tags an extra rusher into the fold.

It sounds basic to say a game boils down to whether one team can block the other. But so often it is the reality. The Cowboys’ offense hasn’t been at its explosive, efficient best over the second half of the season – they ranked 14th in offensive success rate (how they did on a down-to-down basis compared to the historic norms for the down and distance and game state) from Week 10 onwards. On Sunday, the crux of the Cowboys offense-vs-Niners defense matchup will come down to how much the Cowboys’ line can stymie the sledgehammer that will be thrown its way.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Read Optional to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.