Pick by Pick Analysis of the second-round of the NFL Draft

The players, the schemes, the fits, the decisions

The strength of this draft class was on Day Two. Here is a breakdown of each pick from the second round.

You can read a full breakdown of every first-round pick here: picks 1-10; picks 11-20; picks 21-31.

32. Pittsburgh Steelers: Joey Porter Jr., CB, Penn State

It was always going to be Porter for the Steelers. They needed corner help and a corner who’s most comfortable playing in bump-and-run coverage. The Steelers played only 26% of their snaps in middle-of-the-field open coverage last season; 27% of their snaps came in man-free coverage. A bulk of the NFL might be shifting to two-deep-and-rotate defenses, but the Steelers are staying firm. They’re playing with a single-high shell and pressing the everliving crap out of people on the outside.

Porter is a ginormous corner with a massive wingspan. He was closely comped to Deonte Banks throughout the process and, like Banks, there are visions of him growing into a kind of Stephon Gilmore-lite.

I’m not there. Porter is too grabby. He panics. His balance is rickety. He makes too many elementary errors. Of the high-end corners, he had the most turgid reps. Banks, like Gilmore, is patient. They win at the punch, sure, but they’re also whizz’s in the second-phase of the route. Porter wants to be more physical and end the rep before it begins. He punches, he grabs, and he rides that down the field. You can see why the Steelers of all teams were such fans – beyond the family lineage.

That style can work in college. In the pros, the players are too good and the officials too whistle happy. Once he’s disengaged from the receiver, Porter lacks the high-end speed needed to recover, and the short-area twitch to cut in-and-out.

The Steelers know what they’re getting: A bundle of tools that need to be sculpted. At the apex of his game, Porter is a blur of arms and tenacity. He looks like Doctor Octopus out there. But that can only carry him so far. He needs to develop a secondary move after the punch. If he can do that, he has the physical profile to be one of the rare corners who can truly match up with #1 receivers on the perimeter.

33. TRADE: Tennessee Titans: Will Levis, QB, Kentucky

Levis Fever got out of control as we approached the draft. Rumors that he was going to be the pick for Houston at #2 were false. The Colts, fans of Levis, opted to go with Anthony Richardson at four instead.

It was a long wait for Levis, but it worked out the end: he’s landed on a team, and within a scheme, that is built to maximize his strengths.

Taking Levis in the top-10 would have been a reach. But with the second pick in the second round, it represents good value. The small chance that Levis works out makes the risk of moving up to top of the second-round worth it given the importance of the quarterback position.

Levis’ tape never matched up with the first-round hype. It’s tempting to say that Levis is a Marmite figure. But that would be unfair to Marmite.

Teams were clearly intrigued about the idea of what he could become in the future – despite passing on him in the first round.

Why did teams like Levis, then? Why was he ever discussed as a potential top-five pick, besides the economy of the draft? A couple of things. He played in a prototypical, modern pro offense. At Kentucky, he essentially lined up in a blend of the Rams’ and Chiefs’ offenses, which should give him a head-start as a year-one starter over Stroud and Richardson. But most importantly is something I’ve banged on about on podcasts throughout the process: His eyes.

Levis’ at-the-snap processing is excellent. He consistently gets to the right spots on the field with his eyes – at the snap. He knows where he should go with the ball based on concept vs. coverage. He has a good understanding of the pre-snap picture and where he should jump to at-the-snap if his pre-snap indicator is confirmed. The only problem… he doesn’t throw the ball. There’s a hiccup in what he does. Sometimes, he’ll come off that primary read, quick-scan elsewhere, then return to the primary. That pitty-pattering of the feet will mess with Levis’ overall mechanics. He tap-dances as he tries to figure out whether to let go of the ball or not, and in doing so he will either elongate or narrow his base. As that base widens, he loses rhythm, bounce and balance, forcing the ball to come out inaccurately. Too often, he will wind up no longer being aligned with his target — something that was fine early in the rep but that was corrupted by his indecision.

That’s not how Levis has been typecast through the process. As Jon Ledyard noted on our final pre-draft podcast, there are a whole bunch of analysts who looked at Levis’ traits — big arm, can move — and are projecting him as some kind of off-script creator. Some are happy to overlook the technical flaws in the hope that Levis can mirror the kind of in-the-pros boom that we saw with Josh Allen.

But that’s a misreading of the player. Levis isn’t a creator. And as Jon rightly noted, that’s not something that a quarterback learns. It’s innate. They either have the field vision, the twitch, and the capacity to conjure magic from nothing, or they don’t.

Levis’ finest ‘wow’ throws still come in structure. It’s roll out one way and toss the ball 50-odd yards the other way kind of stuff, just the kind that the Chiefs feature in their offense. And that stuff is exciting — and nothing to sniff at. But it’s not the kind of create-on-the-fly offense that’s essential in the modern game. His processing when he has to move from one to two or two to three is scattershot at best. He wants to read-it-and-fire, only sometimes he doesn’t fire.

Levis is more of a distributor than he is a playmaker, which nudges him closer to Stroud on the spectrum of this year’s QBs than Richardson or Bryce Young. His game is built on twitch — he just too often winds up making the wrong call or second-guessing the correct instinct. The idealized version of his game is something approaching on Matthew Stafford: A big-armed bomber who likes to dink-and-dunk and then take shots from five-out sets. As the wide-zone-then-boot offenses across the league look for a path forward, landing on a big-armed chucker with the mental acuity to slice a defense apart from empty is one of the cleanest roads — it’s the road that Sean McVay hit on his way to a championship.

And there’s an added thing with Levis: He’s a legitimate threat as a downhill runner. That’s something that Stafford never possessed, and pushes Levis towards Jalen Hurts’ territory: A lethal weapon from empty who’s capable of carrying the ball on quarterback runs (power, zone, counter, stretch; you name it, they run), making life easier in the dropback game from five-out looks.

That’s the upside the Titans will envision with Levis: A Hurts’ type development curve. And you can make a compelling case for that when you just tot up the attributes: He has the arm, the athleticism, the toughness, and the smarts.

The question, of course, is whether you can coach him to pull the trigger — and when he does, will he be consistent enough with his base to be accurate? How much of his unwillingness to let it fly at the right moment was because of a mental block? How much of it was due to a stanktastic selection of surrounding, umm, talent?

Can that side of his game be de-programmed?

Coaches will be willing to bet the answer is yes — egos and all. They always think they are the ones to fix a fundamental flaw.

It’s a common idea these days that you need a quarterback who can ‘go and get you a bucket’ to survive in the NFL — at least in the postseason. On third-and-whatever, they have to be able to go make a second-reaction play. I agree with that. It’s why Young, Stroud, and Richardson sit ahead of Levis on my board. Levis has the tools that should profile a quarterback as someone who can go get a bucket, but his game and his instincts don’t match up with that style. He’s more of a point-and-shoot, Stafford-esque, let-me-play-ISO-ball QB.

That’s fine! That’s why teams were compelled. They know what he is; they’re teasing themselves that he can become more. Never forget: Coaches and executives are control freaks. Having an athletically gifted quarterback who executes the offense – their offense, goddammit – will, for a certain kind of coach, always inspire a burning of the football loins more so than the player who will go off-script whenever they damn well please. Mike Vrabel doesn’t seem like the sort to be fussed about the artistic stylings of quarterbacks. He wants the ball out — to the right spots, at the right time.

It’s a profile that recalls… Ryan Tannehill. Tannehill is an athletic quarterback with a big-arm. He isn’t an off-script creator. He doesn’t weave magic out of nothing. He plays within the system and has all the athletic tools to execute what’s needed: he has the arm to launch the ball down the field and he’s athletic enough to be a threat to take off as the roll-man on boot concepts.

That’s Levis’ future. The Titans want to be a duo-then-boot team. They want to hammer you with the run and take shots downfield on turn-the-back play-action. If the Levis thing is going to work out, it will be in that kind of scheme. Bouncing between the play-action/boot worlds and empty sets that allow Levis to channel his inner point guard and his impulse as a downhill runner will give Levis his best shot at being a viable NFL starter.

34. Detroit Lions: Sam LaPorta, TE, Iowa

LaPorta being selected ahead of Michael Mayer was a slight surprise. But it makes sense for the Lions. They were hunting traits over polish, betting on Dan Campbell and co. can help coach ‘em up in the run game.

LaPorta was the focal point of a truly awful Iowa passing game. He finished with 18 more receptions than any other Hawkeye weapon in 2021 and 24 more in 2022. Despite that, LaPorta is still raw as a route runner. He’s not a technician; he’s a bulldozer. But LaPorta is electric after the catch. He can break tackles and wriggle by smaller, agile defenders in the open field. It feels like his best football will be in front of him with a competent passing attack.

The issue is how much he will see the field. LaPorta is small by modern tight ends standard. He doesn’t rock anyone in the run game — and he lacks the length to be able to take a more subtle approach to the blocking world. Unless he’s playing fiercely, he’s a net negative in the run-game.

He profiles as almost all those classic Iowa tight ends do: as a functional sixth lineman in the outside zone world who can then go and create magic in the passing game after the catch. And while we often get carried away by the second portion of that sentence it’s the first part that gives the best of the best wide-zone-then-go tight ends their value.

LaPorta has to tighten up as an on-the-move-blocker. He doesn’t have to put a dent in the defensive shell in-line. But there needs to be growth, technically, on the move, allowing him to see more snaps and therefore more opportunities to do what he does best: exploit the middle of the field in the passing game.

LaPorta is not someone who will bounce around the formation. He will play on the line. To unlock the obvious receiving potential, he has to become more engaged and violent at the point-of-attack. Some teams will buy into that as a developmental trait; those that did will have slotted LaPorta at the very top of their tight-end boards.

Look at this as a collection of weapons:

RB – Jahmyr Gibbs

RB – David Montgomery

WR Amon-Ra St. Brow

WR – Jameson Williams

WR – Marvin Jones

WR – Josh Reynolds

WR – Kalif Raymond

There is malleability, contrasting play styles, and a whole bunch of juice. Ben Johnson is going to have fun piecing this puzzle together.

35. TRADE: Las Vegas Raiders: Michael Mayer, TE, Notre Dame

Back-to-back tight ends. The Raiders leapt up to ensure they could grab Mayer ahead of any other suitors.

Mayer isn’t your traditional Notre Dame tight end. He bounced around away from the formation more than the typical in-line guys that come out of the school. There is still an awful lot of good as a traditional combo tight end, though: He is an effort blocker in the run-game who can also punish defenses in the middle of the field. Mayer has a high floor. At worst, he will be a decent-ish blocker in the pros who can be relied upon to win one-on-one in coverage. The question is whether he has the twitch or long speed to be a true game-breaker at the position.

36. Los Angeles Rams: Steve Avila, IOL, TCU

Avila finished his career at TCU playing right guard, but he shuffled right across the offensive line throughout his college career. He played some right tackle. He played some guard. His bet at the next level: sliding to center.

Avila is a bowling ball of a player who is rock solid in pass protection. He has slick feet for someone with his size (330 lbs) and, umm, frame.

Typically, squat, thick linemen aren’t the quickest to pull and move in space. They win by driving people back off the ball and then sinking into pass pro. They’re vertical players.

Avila wins laterally. He doesn’t quite have the slippery footwork to play on the perimeter as a true tackle, but he has enough lateral twitch to be an effective interior guard. His technique isn’t the cleanest, either. He often plays too wide, or concedes his chest and then embraces the hand fight – something he could get away with in college but would struggle with when Javon Hargrave steamrolls through his chest in the pros. But Avila is a cerebral thinker who wants to get better at the technique stuff; he’s self-reflective and works hard.

Few can pull and skip as well in the run game as Avila:

That’s a 330lbs lineman, folks! I mean, come on now!

AGAIN!

On a long-trap play-action shot, no less! Spicy.

Avila has unteachable speed out of his stance.

Oof. I need a cold shower.

Watching Avila split across the formation and cover ground a man his size should not is mesmerizing. Every offense deserves a boulder that can slice across a formation. You have a wrapper! And you have a trapper! And you have a puller!

At times, with his size, it felt like things came easy to Avila in college. He faced a lot of three-down fronts where he was able to comfortably play in a phone box and cover up some of his technical flaws: Sit, drop anchor, shuffle a little bit in pass pro (in an offense that got the ball out quickly) and drops anchor, then clean people out in the run game. Pair him with a top o-line coach early in his career – a Mike Munchak, for instance – and Avila could be a real gem.

In the NFL, his best bet is to move from guard to center. Every team in the league is looking for a cneter who can replicate some of what Jason Kelce and Creed Humphrey bring to the Eagles’ and Chiefs’ offenses – conceptually. To run the true power-spread – the goal offense for the bulk of the league right now – an offense needs the threat that all five linemen can pull and move in space.

Most offenses max out at three or four. The dominance of the Chiefs’ and Eagles’ offense comes thanks to their ability to pull all five (either solo or as combinations). It opens up a whole new world for the offense in the run game, RPO world, and the play-action shots that flow from that. It presents options, and means that no defensive front is safe. Think you’ve set a decent front to take away a team zone-away run style, and all of a sudden here comes a center wrapping around to kick out your edge defender.

Avila profiles as a player who has the smarts and foot speed to push inside permanently, and he wouldn’t be as exposed as a shuffler in pass protection playing with help in the middle of the line of scrimmage. He gave up zero sacks on over a thousand snaps.

It will be interesting to see if the Avila foretells anything about the evolution of the Sean McVay offense. Avila can slot in and play as a guard or center just fine. But the upside of him as a genuine field-tilter as a puller and wrapper from the cenetr spot must surely be too tempting for a guru like McVay to ignore.

The Rams are in the midst of a mini reset. Eyes are on Caleb Williams, or at least what is beyond the current incarnation of the team – disparate parts left over from the Super Bowl run. Is McVay gearing up to re-orient his team in more of the smashmouth-spread model?

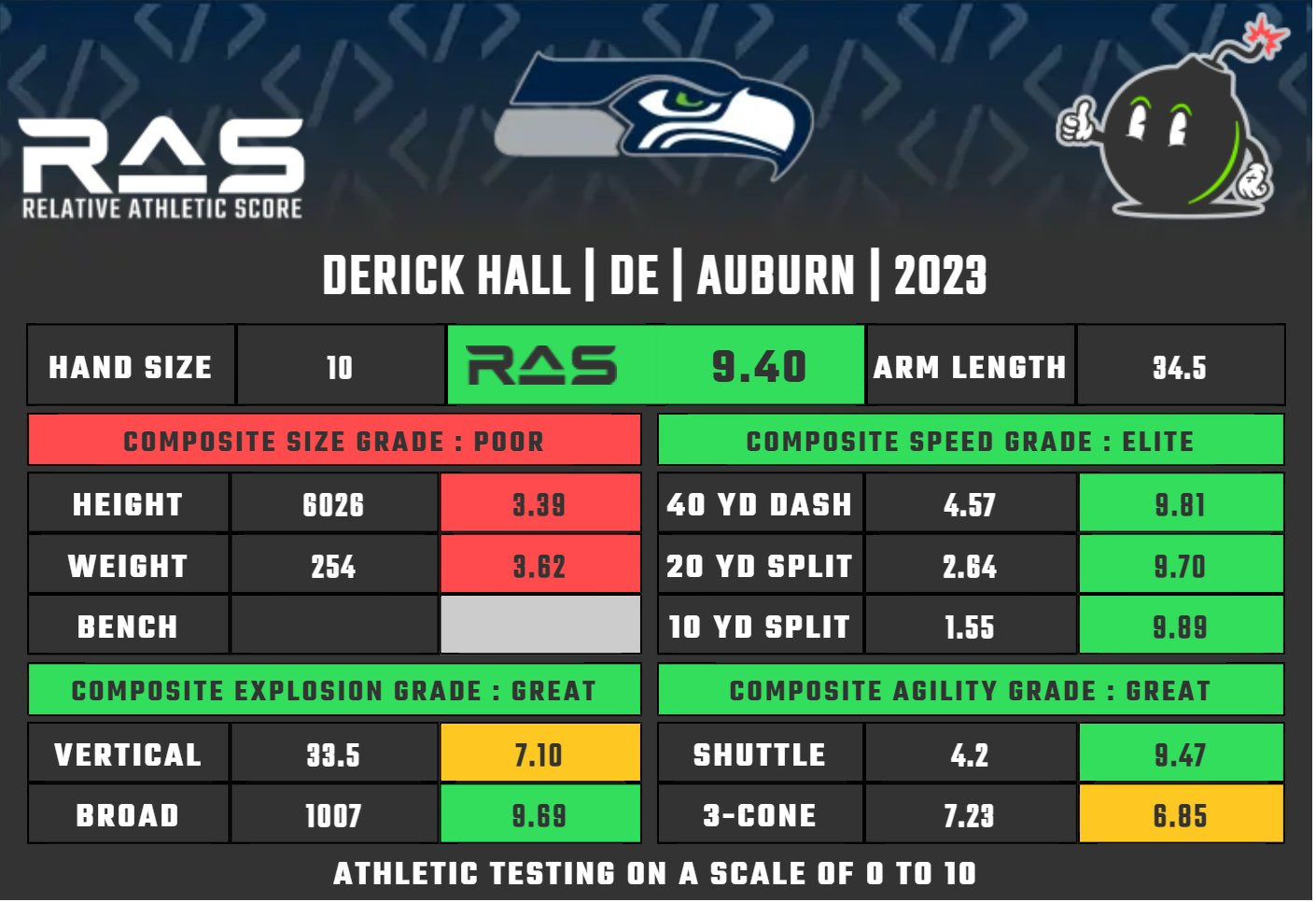

37. Seattle Seahawks: Derick Hall, Edge, Auburn

Hall is a long, explosive, disruptive, effort rusher, one whose play never matched up with the testing figures.

But Hall’s profile fits with want the Seahawks want up front: A long, explosive hustler. If you’re not engaged, Hall will flatten you. He is a gifted edge-setter, too, a valuable commodity to the Seahawks. He’s able to long arm blockers, occupying with them with one hand and twisting and controlling them with the other.

A lot of his tape is average. He cannot sink and dip; he doesn’t have many moves. But Seattle needed depth and talent on their front, and he checks a lot of what they look for in an edge defender.

38. TRADE: Atlanta Falcons: Matthew Bergeron, OT, Syracuse

Bergeron is a twitched-up, rocket off the ball. With Bergeron next to Chris Lindstrom, Kaleb McGary and Jake Matthews, they will have the quickest get-off of any line in the NFL.

The Falcons announced Bergeron as a guard, but he played tackle in school. Arthur Smith has already confirmed that Bergeron will come in and contend for the starting left guard spot, with a long-term view that he could, possibly kick back outside once Matthews moves on.

Atlanta is going to run the shit out of the ball – good news, considering they drafted Bijan Robinson with the eighth overall pick. Bergeron is a springer out of his stance but he wins with technique and angles rather than mass. He doesn’t bludgeon the front off the ball, but he has enough power to get by. He will be a double-and-climb magnet inside, and he is a good athlete in pass protection, if a work in progress. He is quick off the ball, covers a lot of ground, and is a sharp re-director. This is a good pickup for the Falcons for the now and the future.

39. Carolina Panthers: Jonathan Mingo, WR, Ole Miss

Mingo is a height-speed athlete who the Panthers are hoping they can develop into a receiver. He was used in such a peculiar way at Ole Miss (is a wing receiver) that it makes any evaluation tough.

In the NFL, the Panthers will project him as a ‘big slot’ who can get vertical in a hurry and create after the catch. Mingo went down on first contact on just 44% of "in space" plays, per Reception Perception. He is a blur, who can explode away and humiliate people.

How much of that will he be able to do in the league, though? Can he separate consistently from man-to-man coverage? If he’s not being afforded free access releases through scheme, can he get open?

At a minimum, he will be an intriguing toy for Bryce Young to work with. If the play design doesn’t spring Mingo, Young’s ability to extend play and create on his own could buy Mingo time to find space. And if Mingo gets the ball in open air, look out.

40. New Orleans Saints: Isaiah Foskey, Edge, Notre Dame

Back-to-back, defensive linemen for the Saints. And another big end.

Foskey projects as your classic sub-package rusher. He’s an all-power, all-the-time kind of pass-rusher. There is little bend in his game. He’s not going to run the arc and then close to the quarterback. Instead, he’s an out-to-in, crunch rusher, one who wins by driving through the chest of opposing linemen. He can win in close quarters whether he’s tight to the formation or given a runway, which gives him the kind of versatility every defensive coordinator is seeking in the age of hybridized fronts.

Foskey was a dominant college rusher, but questions about his athleticism dominated the early draft proceedings. He doesn’t play with the twitch that teams are looking for in a top-tier edge-rusher. But what he does do – that out-to-in crunch – he does at the highest of levels. It wouldn’t be jarring if some teams have Foskey ahead of the other higher-profile ‘crunch’ rushers: Lukas Van Ness, Keion White, even Tyree Wilson. With Foskey, we’ve seen it, on a snap-in, snap-out basis, no less. The other players are projections in that Trey Hendrickson-like role.

Foskey answered concerns about his general athleticism at the Combine, too: he finished seventh among edge defenders in Next Gen Stat’s total athleticism score, putting him ahead of some classes’ twitchier rushers.

There is room to grow. Foskey will never be a beat-you-your-cleats, every-down winner, but his Combine showing suggests there’s more juice in the tank than detractors had feared. Foskey clearing the ‘passable’ benchmarks for an edge defender would have been a win during the process. Instead, he cleared that mark with room to spare.

There were few questions on tape. Foskey played with good burst off the ball and he uses his length and hands as well as any of this draft’s top rushers. Where he’s limited is in the variety of moves. You have to win in multiple ways in the NFL. For some, that comes through the blessing of athleticism. They can win with speed and power. They can dip-and-rip around the edge; they can run through a lineman’s chest; they can win the hand fight; they win with a variety of moves. Only the special ones can rack up three or four of those, but effective rushers need at least two.

Foskey is a single-path guy right now. Given his size and tenacity, that will be enough to be a solid, 20-snap-a-game, rotational option in year two. To make a jump over the span of his rookie contract, he’s going to have to add something else.

41. Arizona Cardinals: BJ Ojulari, Edge, LSU

The Cardinals needed to get some gas upfront. We know what Jonathan Gannon wants to do on defense. He wants to rely on a four-man rush. He rarely blitzes.

Ojulari will bring burst off the ball. He’s a dip-and-rip rusher with outstanding closing speed. He lacks the length to play on the edge on early downs. He was consistently vaporized in the run game in college. He can get locked on and caught in a runaway train. In the NFL, he’ll be more of a sub-rusher who brings some bounce to passing downs.

His journey from here is murky. Will he get washed out by bigger, stronger, athletic tackles?

42: Green Bay Packers: Luke Musgrave, TE, Oregon State

Musgrave is a crazy athlete for the position. His height-weight-speed phenom who wants to play north-south: let him drive downfield and let him get going in a hurry. When driving downfield, he can dust dudes. Right now, there’s little else to his game.

The Packers will view him as a move piece within the offense. He can play detached from the formation or as a move blocker lined up in the backfield.

It’s an upside play. Musgrave is a limited route runner. Those raw, vertical-only tight ends have had a rough go of things in recent years. The position is too complex, too demanding to be able to get by through hops alone. And any tight end who’s a net-negative in the run game is going to have a hard time getting on the field for a Matt LaFleur offense, no matter how exciting the idea of having a moveable giant in the passing game is.

With how the board fell, it’s good value for Musgrave. It’s a loaded tight ends class, and tight ends went early and often. Taking a risk on a high-upside guy at the position makes sense. But he has a long, long way to go to be a contributor in either phase of the game.

43. New York Jets: Joe Tippmann, C, Wisconsin

I was much lower than the consensus on Tippmann. A big, springy, Wisconsin center is always going to draw attention. But Tippmann is frustratingly inconsistent.

He is tall for a center (6-6, 317) and is an excellent athlete for the position. In Wisconsin’s wide-zone-based offense, they put that to work, utilizing a slash-and-kick style that had Tippmann playing on the move and marching out into space. That’s all well and good as a foundation, as an idea, but the execution too often left plenty to be desired.

Given his size, Tippmann doesn’t have the natural leverage advantage that most centers bring to the party, and he hasn’t proven to be a good enough technician to overcome those concerns.

Tippmann doesn’t create much of a surge off the ball:

His balance is scattershot. Rattle through any game, and you will find Tippman consistently on the floor.

A center not delivering a death blow at the point-of-attack is fine. But if they’re unable to win on contact, they have to be able to win once engaged. Tippmann is up-and-down. Too often, he gets caught outside, unable to latch onto the interior of lineman’s pads to shake and move them where required.

Tippmann tested as a better athlete than he played, too. He is a good athlete in the run game, but not a great one. He’s fine slicing laterally, jutting across the formation or kicking out into space as a puller or wrapper:

Wisconsin did some cool things with pivot footwork to take advantage of Tippmann’s footspeed at his size. They’d bluff a concept one way, with Tippmann taking an initial jab step towards the fake action, before he pivoted back away to lead the charge to the true point of attack

That stuff is spicy – and not easy. But the innate side-to-side agility doesn’t show up when pushing ahead, be it in leading the way on wide-zone runs or climbing up on double-and-climb concepts. When Wisconsin tried to feature Tippmann in the screen game, he was always a half-beat behind the action.

His athleticism doesn’t show up in pass protection, either. Tippmann does not look fluid sinking back into pass pro, and he has a tendency to narrow his base on contact while playing with the same-old, same-old wide arms that get him in trouble in the run game:

The player he could be with his raw skills doesn’t match up with the player he is today.

Still: Tippmann’s skills will translate to the NFL quickly. He played in a run-game that’s the base for the vast majority of the league at this point, and some of his extracurricular pivot work will intrigue staffs across the league. But there is a ton of stuff to clean up, from his feet to his contact balance to his hands. Those are not quick fixes. The upside: one (the feet) can lead to unlocking the rest.

Tippmann is the kind of traits-based player you take based on their upside, hoping that it all comes together by year three or four – and you just have to live with the flaws in the early goings.

That will work for the Jets. Aaron Rodgers’ timeline will speed everything up. But the Jets don’t need Tippmann to be an All-Pro from the get-go. He just has to be competent. On an interior with Alijah Vera-Tucker and Laken Tomlinson and Rodgers at quarterback, he should be inoculated from being exposed early in pass protection early on. And he can be a weapon from the jump as a puller and mover in space. The Jets have amassed a five-man group full of plus-plus-athletes; they’ll be able to do some creative things in the toss and sweep worlds with Mekhi Beckton and Max Mitchell alongside the juice on the interior.

44. Indianapolis Colts: Julius Brents, CB, Kansas State

After the tier-one guys, Brents is probably the best fit for the Colts at corner in this draft. We know what Gus Bradley wants at corner. He’s never changed. It’s long, lean, press-and-trail guys, those who have the size to bump up and dislodge receivers at the snap, the smarts and intellect to hand receivers off on match concepts, and the instincts to go and attack the ball in the air, undercutting routes.

Ding. Ding. Ding. Ding.

It’s always nice when a prospect's athletic measurables match up so cleanly with the tape. Brents was one of the cleanest prospects on tape heading into testing season, and he aced that offseason assignment, too.

Brents played for three seasons at Iowa where he served as a backup before transferring to Kansas State. But that spell at Iowa has given his game a nice underpinning. Iowa’s defensive structure is relentlessly man-coverage oriented. Kansas State’s defense sits more in the zone/match worlds. In 2022, K-State ran a ton of spot-drop coverage, with corners sinking to depth and standing there, not relating to receivers once they entered their sphere.

Having an understanding of those two different worlds gives Brents an advantage heading to the league. He’s taken plenty of reps in each (despite an injury during his sophomore year), and that advantage wil give him a shot to be a contributor from the jump in the league.

Where the Colts will be excited, though, is the idea of pairing that intellect and experience paired with otherworldly athleticism. Brents ranked third among corners in Relative Athletic Score (RAS) over the last five years, per MathBomb. He finished with a near-perfect 9.9 score, nudging up against the ever-elusive 10.0 mark, one that only Deonte Banks (!) and Zyon McCollum have hit over that span.

Neither Banks nor McCollum had the kind of schematic background that Brents is bringing to the party.

Some players are fun to watch because they’re technical savants. Some because of eye-watering athleticism, the kind that seems as if they’ve been CGI’d onto the field. Brents might be the most what-in-the-what, how-is-that-possible player in the class. He just looks different standing on the field, in a way mirrored only by the likes of Kyle Hamilton in recent years among his secondary cohort.

Yep, that’s real.

There’s something extra with Brents, too. He plays with what can only be described as a degree of shit-housery. It belies his build. He may be a string bean of a cornerback, long and limb-y, bordering on gangly, but he remains an intense, active, physical defender. The competitive intensity leaps off the film. Brents isn’t satisfied with just beating receivers. He wants to embarrass them.

His effort ebbs and flows in the run game. But when he’s willing and engaged Brents has shown that he can be physical at the point-of-attack.

When asked to slide down to edge – as he was consistently given the amount of spot-dropping zone coverage – Brents showed he had a good aptitude for team-construct defense. And he was happy to hand out some extras after the play. Oh, you thought you rock me? Slender guy am I? Gangly? Ha. Good luck. Bleep you.

You best believe that kind of stuff gets executives and scouts all sorts of tingly in the football loins.

You can tell Brents loves to play. Does that matter? To some, the answer will be no – or at least that a love of playing can be overrated. But it’s certainly worth noting. The best defensive players, no matter their mental acuity and technical acumen, play hard and run like hell.

“You can’t compromise football character,” an executive recently told veteran draft sage Bob McGinn. “If they don’t love football and they don’t know how to work, it’s going to be hard for them to become who they should become.”

I get it. Reading that can sound like an old scout yelling at clouds. It also just so happens to be the truth.

Coaches raved about Brents’ attitude and performance at the Senior Bowl. In one-on-one drills, he took pleasure in putting clown suits on whoever happened to line up across from him, and he was happy to let everyone know it.

And he wins – a lot.

He has nimble feet for a giant.

Brents is still figuring out how those long, toothpick arms can be useful.

There is more work to be done. Kansas State played a lot of zone-coverage. In press-man, Brents has all the tools to be a success, but there’s still work to be done on the timing and location of his punches. His radar isn’t always accurate. Against average opposition, that’s fine. Brents was simply too long for any receiver to return fire.

Against top-tier competition, holes in his technique were exposed:

That’s Quentin Johnston — the top receiver on my board. Johnston is a master at shrinking his strike zone. He’s a big corner who wants to play small, so he condenses and closes his frame to limit how much space there is for a corner to target.

Check out the rep a time or two. One-on-one against Brents, Johnston bursts open. Brents goes for a two-hand pop. But he plays wide. Johnstone shrinks. Brents is longer than Johnstone. He should be able to put a clamp on the receiver before Johnstone can even get into his route, let alone shake free, right?

Not quite. Length gets draft analysts and scouts all sorts of excited but if you don’t *JOKE REDACTED BY EDITOR*

Johnstoe taught Brents a lesson about the importance of timing and location of press coverage. Brents beat Johnstone to the punch a fraction early, but he was too wide. He laid a glove on Johnston, but not a true punch. Johnston, in contrast, delivered one, short, sharp, explosive pop, timed just as he wanted to exit his break, and not a moment earlier.

Brents was in a solid position. He probably felt comfortable within the rep. And then, all of a sudden. Thwack. Johnston was gone.

That wasn’t a one-time incident. Johnston lit Brents up seven times in straight man-to-man, press coverage. It was the same formula each time: timing and pop can beats length and passivity.

Losing those opening exchanges had a knock-on effect. As the matchup against Johnston unfurled, Brents was fed up with losing. So, he decided simply not to engage in the hand fight at all, to play the show and mirror game, a no-no against a receiver with such short area quickness.

Oops. Checkmate. Game, Johnston.

That’s fine. Johnston is really good player. Brents will want to burn the tape, but it will likely wind up being a good learning exercise. For some corners, that sense of timing in the punch comes naturally. For others, it takes time. Brents has shown some latent feel for how to use his unnatural frame to prod and guide receivers to different landmarks, something that can be just as valuable (and is the benefit of having those long arms) as delivering a vicious strike.

Signs of growth are there – and that’s all that really matters. Brents isn’t raw in press, he’s inexperienced, a small but crucial difference. With time, his technique and instincts up on the line will improve.

The only other knock is his playmaking. Brents finished tops on the Wildcats in INTs and pass deflections, but a raft of those had little to do with Brents feel or instincts in zone. Balls arrived his way. Poor quarterback play and pressure up front led to throws being tossed in his direction, untouched. He didn’t fight and scrap in the air to win the ball, and he left plenty of opportunities on the floor:

Brents gets to the right spots, but he doesn’t always finish.

Here, there are more signs of growth.

That’s an exciting development.

That’s not a corner being bailed out by his athletic profile. That’s a corner using his smarts to execute once he’s been beaten early in the rep. He played through the rep, played through the man, and attacked the ball. That’s all you can ask of a corner. They all, at some point, will get beat. Do they have the athletic chops and instincts to recover, not only in terms of the distance but in being able to go and make a play on the ball?

It would have been easy for Brents to get tetchy there, to go hunting for the ball over their head, or to arrive at the collision point early, frantic about giving up an explosive play. Instead, he remained patient. And he made the play, not because he’s an explosive leaper or because he has the wingspan of a Pterodactyl, but because he played with patience and smarts

Brents might never be a playmaker. Those concerns are fair. But his growth as a recovery defender and his length mean he should, at minimum, be a pass breakup and tipped ball phenom – and tipped balls can land anywhere.

Brents thrives in areas that don’t show up on a stat sheet. His feet and wingspan eliminate routes before a quarterback can even take a half-beat to think. He leads the nation in my totally fictitious “yeah, you know what, I’m not throwing to my guy against that guy” stat.

Keep your eyes on Brents at the top of the screen. Watch how he’s able to keep his eyes in two places at once: on the receiver to his side and the back releasing out of the backfield. He’s waiting on the receiver to commit and the route concept to unfold before he hits the gas. He doesn’t want to press back into his deep zone, offer up too much of a cushion or eliminate himself from being able to rally down to close on the running. Instead, he’s patient. He shimmies along. Once he has confirmation of the concept, as the receiver plants and fires, he’s off. Boom. The burst is effortless. He gets zero-to-60 quicker than the receiver is able to press from fifth-to-sixth, looking to pull away.

It looks like a nothing rep, but it’s important. Brents isn’t as instinctive in attacking the ball as any prognosticator would like him to be. There’s a hitch in his get-up at times – times when he’s too patient when he should fire. But what’s not captured in the noise of corner numbers are all the route paths they eliminate. Through his patience, eyes and athleticism, Brents closed down a corridor to the receiver, and gave himself a shot to rally and make a play underneath if he was called upon.

Up in press, his long arms give him an advantage, just as they do when arriving at the catch point. But he doesn’t use those arms as an excuse to play off the pace in zone. He’s always alert. His eyes are good. By physical profile alone, Brents will be pigeon-hold as a bump-and-run, man-coverage corner who can slot into some press-and-trail based groups. And that’s certainly why he will have been pinend right near then top of Gus Bradley’s personal draft board. But there’s more nuance to his game than that; his game is more schematically versatile than his measurables would suggest. Every team in the league will be interested.

Injury concerns kept Brents out of the first-round. But he has the talent to be an impactful player from day one. He should start for the Colts from Day One.

45. TRADE: Detroit Lions: Brian Branch, S, Alabama

Briand Branch and Chauncey Gardner-Johnson on the same defense! Are the Lions trying to monopolize fun!

The Lions likely knew they had to jump to get ahead of the Patriots on this one. A savvy, instinctive, position-free defensive back out of Alabama? Bill Belichick might have fallen on a banana skin trying to race to the podium.

The Lions’ defensive back room is now chock full of talent: Emmanuel Moseley, Cameron Sutton, Kerby Joseph, Tracey Walker, Ifeatu Melifonwu, Gardner-Johnson and Branch. That’s a ludicrous number of malleable playmakers for Aaron Glenn to work with. That secondary isn’t quite motion or shift proof… but it’s pretty close. Glenn will be tapping his fingers together like Monty Burns thinking of the possibilities.

Do they have number one play to lock onto star receivers? Not quite. But that kind or versatility on the back-end will allow them to get creative with coverage and disguises to try to offset some of that concern. Offense is about stars. Defense is about weak links. The Bengals have been to back-to-back AFC title games by making sure their cornerback room had competent players across the board. They didn’t have stars – that was saved for the safety room. They had versatile pieces who could shapeshift snap-to-snap and week-to-week.

The Lions are building something similar.

Branch feels like a capper to what they’ve done this offseason. If you’re just totting up the most fun players to study in this class, Branch would be near the top. He played the ‘star’ role in Nick Saban’s defense, and he’s primarily a nickel corner, but he can move around. He has the aptitude to move back off the ball, despite playing only 100-odd snaps as a free safety.

He doesn’t have the range to play as a true free defender deep in the defensive backfield. But he can play as part of a two-man tandem, covering half the field and attacking downhill from depth.

He can move and roll all over the place pre-snap, which would help make up for some concerns about his natural agility. He also played a bunch as a dime linebacker in Alabama’s system. At his size, that might be tough in the NFL, but he plays the run with such ferocity and authority that he will be able to get away with it in spurts.

There will be plenty of teams who look back on this weekend with regret that they let Branch pass.

46. New England Patriots: Keion White, Edge, Georgia Tech

With Branch off the board, Belichick and co. took a swing on a high-upside pass-rusher.

White is another bouncy swooper who wins with first-step quicks around the edge. He’s heavier than Smith, standing at 286lbs, which gives him an edge. White is still learning, he played tight end at Old Dominion before transferring to Georgia Tech to play defense. Often, he looks lost: he fires off the ball too upright; he plays with a lot of wasted movement; if he’s not synced up, he can be rocked on contact. For someone who’s built to deliver powerful blows, he spends a lot of the time rolling around on the floor having been knocked down by floaty tackles.

He’s so limby, with such arrhythmic patterns, it sometimes looks as if different parts of his body are moving at different rates. But he’s further along in his development than someone like Tyree Wilson, with a similar athletic upside. When everything is timed up, he plays with rare torque. He is explosive in his lower half and can arrive at the point-of-attack with serious power. He has as many – if not more – ‘wow’ plays than all-but the top-tier rushers – and he’s pretty much on par with those guys, too. It’s the consistency that’s missing. White’s best football is ahead of him. The Patriots are banking on what’s to come.

47. Washington Commanders: Jartavius ‘Quan’ Martin, S, Illinois

Fun fact: Martin might not be the most impactful safety on his own team. That might be Sydney Brown, the other Illinois starter, who was selected by the Eagles in the third-round. And that would make Martin the third-best Illinois DB in this draft alone.

Like Brian Branch, Martin is a nickel more than he is a true safety. In Washington’s scheme, though, he could make more sense as a roaming, buzzing safety.

The whole Illinois secondary is vicious, and Martin is no different. He zips around with a zeal bordering on hyperactivity.

He flies to the ball, whether on the ground or in the air. He plays with great instincts when flowing from depth.

Martin split time at Illinois between playing as a free safety, as part of a two-man tandem in split-safety structures, and aligning in the slot. He is a serial gambler, happy to vacate the scheme if he thinks he has a shot at making a play.

There’s a feistiness to his entire style that is intoxicating, the same kind of look-at-him-fly, watch-him-hit style that has Devon Witherspoon slated to go in the top-8 despite his size.

Height and weight are a concern with Martin, too. He’s 5-11, 194 lbs. Is he big enough to have the range to play as a true free safety? And if not, is his technique good enough for him to play in the slot? Even if it is, at that size, will he be overpowered by the new breed of power slot receivers? And if so, as touched on earlier, will you have to flip the matchups, sticking your boundary corner into the slot? And in that world, does Martin have the skills to play as a boundary corner? If not, is it worth the compromise to take an undersized speedster?

He might be undersized, but Martin plays with an aggressiveness bordering on violence. He snarls.

My dorky analytical friends may disagree, but there’s a value to being so physical. As Brandon Staley infamously said:

“What you need the running game for is the physical element of the game. There's a physicality to the game that's real, right? If you're just a passing team, there's a physical element to the game that the defense doesn't have to respect. And that's the truth. Because the data will tell you that you don't need a run game to play pass. You don't need that. But what the running game does for you, it brings a physical dimension to the football game.”

This is a game played by humans. Getting hit really, really hard hurts. Some sacks take more out of a quarterback than another. Not all tackles or rushing yards are made equal. Some take an extra toll.

Martin might not be the strongest thumper on his own team, but he’s as near as makes no difference. And it’s a willingness, at his size, that’s striking compared to the rest of the class.

The question: Where will he play? Being able to toggle between positions is a great skill. But where will Martin feature for the majority of his snaps? Can he truly play on the back end? At that spot, Martin’s instincts are strongest. In the slot, he’s liable to gamble, to get turned around, to concede too much ground early in the rep, and then be forced to play catchup.

Communication issues dogged his time playing inside, unless he was locked into man-to-man coverage. Too often, when playing off the ball in the slot, he would be caught flat-footed and have to play catchup.

He was toasted a number of times by double-moves or switch releases, struggling with when to close the distance.

He can look awkward dropping into space from the slot, unsure of his landmark or the most efficient way to get there:

When pushed closer to the line, though, when able to engage early, Martin was consistently on point.

It’s the inverse on the outside. Martin is quick enough and slick enough to keep up in off-coverage when he has safety help inside and the sideline as an additional defender, but he doesn’t have the size to play out there full-time.

Martin can be too eager to get involved from that spot, too, abandoning his post:

That chase-the-ball style doesn’t work at corner. But you know where it does? Lining up off the line and flying around from depth.

When sitting back as the lone ranger in the middle-of-the-field, Martin is a difference-maker. You can see that he’s operating on a different frequency than everyone else.

When playing from depth, Martin flies around with a simmering self-assurance. His instincts are excellent. He covers a ton of ground, both sideline-to-sideline and when driving down to defend the run.

Pushing Martin back from corner to safety full-time, with the ability to slide into the slot as and when needed, is his future. Ask him to play see-ball-get-ball football, and he can dart around with the best of them.

The Commander's selection of Emmanuel Forbes in the first-round tips the teams schematic hand. Martin roaming around as a half-field safety who can lock on when needed in the slot is an ideal piece to supplement the Washington secondary.

48. TRADE: Tampa Bay Buccaneers: Cody Mauch, IOL, North Dakota State

There has never been a more Jason Licht pick than Cody Mauch. The Bucs GM loves small school, line prospects. And Mauch is the epitome of the small school, line prospect.

Mauch was a tackle at North Dakota State who projects to play along the interior in the NFL, be that at guard or center. He can play any position along the offensive line. The Bucs will likely work him into the morass of guards they already have on the roster and move Luke Goedeke out to right tackle. Mauch is an electric athlete, with outstanding short-area speed and sonar-like radar when pulling and moving in space. A former stand-up edge defender, Mauch converted to the offensive line, added close to 100lbs, and somehow kept his hops.

Some linemen are quality pullers and wrappers in small areas and can pull to the perimeter. Others are weapons – the kind you want to feature in your offense; the kind you build full screen, toss and sweep packages around.

Mauch is one of those guys. He’s a tough, point-of-the-attack brawler. But it’s his balletic feet that will get o-line coaches all hot under the collar. Not since Ali Marpet has a smaller school interior prospect had the same blend of venom, smarts, and zip (for those keeping tabs at home, Cole Strange won through angles and intellect rather than raw power).

Can he hold up in pass protection at the next level? Mauch is an impatient pass protector. He wants to engage early in the rep and finish business before anyone has even nibbled at the croissants. He’s downright rude. Mauch embraces the fight. Even when his technique was exposed, Mauch was able to get by through a cocktail of effort and ferocity.

That worked against overmatched pass-rushers. But it also left him exposed to counter-moves and power-rushers, ones capable of marching him back into the quarterback’s lap.

Mauch was rarely left to sink and swim on his own in pass protection, which should aid his transition inside. Knowing when and how to doll out the punishment is what comes next — being too eager to deliver venomous shots can get a lineman in trouble as much as being passive. But he’s a cult favorite for a reason: He wants to be the most physical lineman in football, even if he’s not technically the best.

Whether it’s at tackle, guard or center, or some combination of all three, Mauch will have a long career.

49. Pittsburgh Steelers: Keeanu Benton, DL, Wisconsin

The pick of the day, for me. Admittedly, I like Benton more than most. But this represents tremendous value for the Steelers.

Benton has the ideal frame and burst for an interior lineman – 6-4, 315lbs. He plays with outstanding strength and balance in his base and strong hands at the point of attack. He is rarely, if ever, moved off his spot. He’s quick enough to wreck the backfield off the snap, and has the strength and body control to hang in a rep and collapse things once in flow.

He can play anywhere along the interior, in any scheme you demand. He is an outstanding team construct run defender, and four or five times a game he is just going to take over.

The question is whether he can develop as a true three-down player. Right now, his pad level stinks, which limits his get-off and effectiveness as a pass-rusher. His in-line strength and body control can help cover up flaws in the run-game. But he plays too upright and wide in the passing game to be consistently effective. By playing high, he loses leverage and momentum on contact, forcing him to stop his feet and then restart.

He is inefficient as a pass-rusher.

The flashes are tasty. He certainly has the torque, the balance, the hands, and the closing speed to be an effective interior rusher. When he gets off the ball with the correct pad-level, he can collapse things on his lonesome. But he remains a work in progress as a pass-rusher.

On a team with Cam Heyward and TJ Watt, that’s fine. Benton can work as a two-gapping, run-clogger on early downs. Any pass-rush upside would be a bonus.

50. Green Bay Packers: Jayden Reed, WR, Michigan State

Reed is a fascinating prospect. His individual traits belie the player that he is on the field. Reed is quick with good long speed. He gets to top speed really, really quickly. Most importantly: He makes tough, contested catches. He battles at the catch point. He makes a crazy volume of catches on contact.

At Michigan State, he ran a pro-style route tree. Or, at least, a version of a tree that will marry up nicely with what he will do in the pros. He often served as Michigan State’s intermediate target, but with enough juice to plant his foot in the ground and get vertical when needed. Those two elements dove-tailed with each other nicely. His smoothness out of breaks made him a reliable target at the intermediate level. As defenders clamped down to break on that return-to-the-quarterback stuff, he was able to crank it to another gear and breeze downfield.

As he matures, he will add head nods and fakes to his repertoire. Right now, the disguise elements of his routes are that he’s so damn good on intermediate, in-breaking routes that corners want to beat him to those landmarks. When he makes breaks off that idea, he’s able to move into space — defenders overplaying the in-break.

The big concern: Does he create enough separation? If those head bobs and fakes arrive over time, he should do. Right now, it’s an issue. Reed finished with a 64.7% contested catch rate in college. If he’s not able to consistently uncover from man-coverage late in the route, it will reduce the margin of error for the quarterback. For a veteran, that’s old hat. They know they know they need to be precise. For Jordan Love’s first year as a starter, it’s a slight worry: will the QB be willing to let the ball fly if the receiver is always in-phase with the opposing corner?

Matt LaFleur might be able to spring Reed open more comfortably through play design. And if he’s able to get downfield, he can be a reliable, middle-of-the-field weapon. In an offense that prioritizes hitting chunk plays to the middle chunk of the field, that’s invaluable.

51. Miami Dolphins: Cam Smith, CB, South Carolina

Opinions on Smith were all over the place in this class. He was the 22nd overall player on my board and the fifth cornerback. Thanks, Vic, for having my back.

Smith is an instinctive playmaker who lacks some of the high-end athleticism that is coveted at the position. Given his lack of springs, it always felt like he would slide into Day Two. There were also character concerns swirling around Smith: he consistently got into tussles with his coaches on the sideline. Public displays of frustration were frequent. How will that jive in a locker room with Jalen Ramsey and Xavien Howard?

Mike McDaniel doesn’t seem to care. He wants good, smart, instinctive players. And Smith fits that model.

Smith is a wizard in match coverages. He knows where to be. He arrives in all the right places at all the right times. He is quick in his transition from back-pedal-to-drive. He relates well in off-coverage, and has mastered subtle dark arts to stay tight to receivers once he’s picked them up in zone or off-man coverage. Smith rarely, if ever, gives up big plays. He rolls in and out of breaks like a receiver – and he makes a ton of plays on the ball. He has outstanding short-area quickness.

Smith was always going to fall behind some of the athletic phenoms in this class. But it’s hard to picture a better landing spot for a Fangio-style,

In the Book of Fangio, Shawn Syed wrote of Fangio corners:

“Vic Fangio has recently coached cornerbacks like Patrick Surtain II and Chris Harris Jr. Cornerbacks need high-level coverage skills, but the Fangio Defense also uses cornerbacks as force defenders in the run game.”

That last point is important. Smith is a walking computer. He will download all of the necessary info for the battery of Fangio coverages – and he will make a bunch of play on the ball. But how will he hold up as a tackler? He’s battled injuries throughout his college career. And while he’s a willing tackler, Smith too often whiffs. He’s eager to deliver strikes, rather than playing with technique. He finished his college career with an eye-watering 16.3% missed tackle rate.

For a Fang’s defense (or any defense in the NFL, really), that’s unacceptable.

If he stays healthy, Smith will be an impactful player from the jump in coverage. Where he slots into the Dolphins’ talented batting lineup will be interesting. Jalen Ramsey to dime linebacker, anyone? (I’m going to make this happen!)

52. Seattle Seahawks: Zach Charbonnet, RB, UCLA

Hahahhaha *deep breath* hahahahahaha.

The Seahawks cannot help themselves, can they?

How can you not love Charbonnet? Everyone loves Charbonnet. He’s a one-cut-and-go, physical back. He has a compact frame and is a decisive runner. He can run over people. He can run around. He plays with excellent contact balance, and once he’s up free to the second-level, he has breakaway speed.

He is the prototypical NFL back. You can slot him into any scheme and he will have a role: He’s an excellent checkdown back; he’s patient following blocks on gap-scheme concepts; he shows good vision, patience and burst as a wide-zone runner.

Charbonnet does everything at an eight out of ten. He should be a really productive back. Whether it’s a good use of resources for the Seahawks or not is a different question (spoiler alert: it’s not). But it will be fun to watch the one-two, Charbonnet-Kenneth Walker punch on Sundays.

53. Chicago Bears: Gervon Dexter, DL, Florida

Is Dexter a great player? No. Is he fun? Yes. And I support fun things.

The Bears seem intent on taking as many swings on big, uber-athletic interior linemen as possible. If you want to run a four-down-then-get-depth system, with passive coverages on the back-end, you need a couple of things: A hellacious pass-rush; great athletes along the interior, to allow you to run the kind of stunts, twists and games that can help offset the limited pressure/blitz menu; dynamism and length at linebacker.

Dexter checks the middle box. He is a raw prospect with shocking mobility for a lineman of his size. Dexter weighed in at 310 lbs standing at 6-5 at the combine. As a pure athlete, Dexter finished with the 77th-ranked RAS score among interior linemen dating back 1987.

At just 21-years-old, Dexter is a diamond ready for polishing… but it’s going to take patience and plenty of polish.

He shuffled around the Flordia defense front. In odd fronts, he played in heavier roles, lining up as a nose tackle or one-tech and serving as an anchor-point versus the run. In even fronts, he was moved into pass-rushing spots, lining up as a three-technique in split-fronts (two three techniques in a wider front) or holding the inside position in overloaded fronts.

Dexter has the innate size, burst, and athleticism to be p-r-o-b-l-e-m at the next level. He moves in sudden directional jolts. There is a lightness to his game for someone of his size; he plays with a balance and agility that should not exist in someone of his size.

Did you spot the flaw there? Did you notice how quick Dexter’s first step was, how he was able to leap from one gap to the other? Did you also notice how long it took for that first-step to arrive? it’s as though he’s operating on a different time-frequency from everyone else.

That’s the one crucial issue: Snap speed. Well, not snap speed exactly. It’s more snap anticipation.

Dexter is late off the ball constantly. It’s not he doesn’t have torque or burst… he just doesn’t get out of the starter’s blocks. Canvas the film, and you will be stunned by how on nearly every damn rep he’s a half-beat behind everyone else on the football field (#9):

Again.

Again.

Again.

I could go on. Dexter’s delay has a concertina effect: linemen are able to slip into their stance quicker; the advantage he gains from being such a quick-twitch athlete is handed right back to the blocker before he’s even been able to rise out of his stance.

It’s a problem. Even the great plays so often come after the Dexter Delay — there are some outstanding reps in those above clips. He was able to get away with conceding ground in college. In the pros, that half-beat is everything.

Can you develop and teach snap anticipation and quickness? That depends on who you ask. Ask a solid sample of coaches and you’d get a split reaction.

But it’s impossible not to be infatuated by the possibility of what Dexter could be. There are few other linemen in this class (or indeed any class) with his combination of size and lateral quickness. His testing results were poor, which is a concern. But he played much quicker and more agile than he tested. The good reps, though, good God, the good reps.

Sheesh.

Dexter’s gap-leaping ability can create chaos inside, even if he’s not the defender to come screaming home.

Usually, giant interior linemen can be a concern. Standing at 6-5 gives away the natural leverage advantage that squatter interior defenders use to their advantage. But with Dexter, it remains a plus. His value will come not as an interior clogger, but as someone who can roam across the formation. He has short arms, which might limit some of his value as a free-mover in the league. Can he push all the way to the edge? No. But can he replicate some of the work he did so effectively in Florida’s pressure packages, working as a key cog in a pressure pathway, an athlete who opens up possibilities for everybody else rather than mauling linemen on his lonesome? You bet.

Oh, and can he occasionally overpower whoever the heck is in front of him and walk them back into the quarterback? Sure thing.

Dexter is more of an overwhelmer in the run game than a technician. He got by, mostly, on being more athletic than his opponent rather the out-crafting them. But the signs of development were there. He isn’t a mauler off the snap. Rather, he wins by hitting landmarks others cannot by way of his quickness. And he tested poorly in strength tests at the combine. But he’s shown a nascent understanding of how to control and cajole linemen, and how to exploit his true strength — that get-off. Dexter isn’t an in-line bruiser, but it’s smart with his body positioning, and he has enough pop in his mits that he can push to depth and then control linemen with one arm, fracturing the front and forcing ball-carriers off their path, while keeping one arm free to go make a play.

Given where he’ll lineup in the NFL, that’s more than enough.

His versatility — the ability to bounce from a two-gapping nose to an upfield rusher — paired with his athletic profile is enough to make Dexter an early second-round pick. Some time might even get wide-eyed and take him at the foot of the first round.

I get it.

Dexter’s best football may well be in front of him. But there also aren’t many prospects in this class who have shown they can hold the point as the nose in odd fronts and slide naturally into the kind of overloaded and split fronts that are en vogue in the NFL. Most prospects can do one or the other; they dominate in one and flash in the other. Dexter was good in both, with the same flaw (snap anticipation) undercutting both. Montravius Adams is the closest comparison. It’s never fully come together for Adams, but he continues to hang around the league because of the promise of what might be and the flashes that are dotted throughout his game.

Adams is more of a tweener — still. The hope would be that Dexter could someday become the full package.

There are more polished prospects than Dexter. But he has an intriguing set of skills. It will be interesting to see if they ever come together.

One slight concern with the fit in Chicago: Dexter fits what Eberflus wants schematically and in terms of athletic make-up, but with what’s on the Bears roster he’s going to need to play right away. And Dexter needs development and time. The scheme fit is great; the development arc is not ideal.

54. Los Angeles Chargers: Tuli Tuipulotu, Edge, USC

Tuipilotu was extremely productive at USC. He bounced around the defensive formation, playing some as a heavy-5/4i inside the tackles before kicking out to a pass-rushing, wide-9 spot.

How much of that production is replicable at the next level, though? Tuipulotu felt like an excellent college player. He doesn’t have one, defining trait. Everything is good to very good, across the board.

He’s not a whirlwind of fury running around the arc. He doesn’t have heavy hands. He has long leavers, but they often served him more to keep blockers at bay in the run game than as a pass-rusher. He doesn’t bring much torque to the point of attack for someone so big; he doesn’t play with great burst or bend.

Tuipulotu is a savvy rusher. He is solid. He won – a lot – from every alignment imaginable. He moves smoothly for a big man. As a rotational rusher, there is some upside. And with experience playing as 4i, he fits into Brandon Staley’s scheme (whether you want him in that role in the pros is another matter entirely. Most teams would not, but Staley thinks differently.)

55. TRADE: Kansas City Chiefs: Rashee Rice, WR, SMU

This is a fascinating pickup. Rice was a headliner on my Day Two 22, and the seventh receiver on my board.

Confession time: I’ve spent the last two years rethinking my approach to receiver evaluations. I checked myself into an Evaluator Clinic and secluded myself in a dark room. What followed: Introspection and self-flagellation. Why, oh why, did you like Laquon Treadwell? I went cold turkey. No more JJ Arcega Whiteside’s.

I returned from the darkness having found the light: bank on the guys who get open.

I realized that too much of my focus was being placed on the mechanics of the receiver position. I focused on each individual tree, too often missing the forest. All that matters, in the end, is whether the guy gets open or not. The hows and the whys are somewhat important, depending on the schematic makeup of the offense. But any offense can shapeshift to include a fella who is able to uncover from man-coverage or who consistently finds the soft spots in zones.

So it is with great regret that I report a minor relapse: Rashee Rice has my ears perked.

I wouldn’t consider myself sold on Rice. This whole receiver class oscillates between ‘meh’ and ‘oh, okay, he’s kind of interesting’. Within that context, Rice stands out: He’s an explosive leaper who is a true vertical threat. He isn’t an in-out, twitchy route runner. He doesn’t create as much separation as consistently as you would like. But he has otherworldly body control, and strength at the point of the catch. He can twist and contort in the air even as being dinged by defenders, and he can create throwing angles for quarterbacks that very few players in the league can replicate.

Concerns about his all-around athleticism were obliterated at the Combine. Rice leapt out of the Lucas Oil ceiling, finishing in the 93rd percentile with his ten-yard split, in the 95th percentile in his vertical leap and in the 85th percentile in the broad jump. The upshot: The explosive leaper on tape confirmed his athletic chops when jumping and running in his pajamas. He’s not a sprinter. He’s not swift in and out of breaks. But he’s a rebounder who can stuff a put-back with the best of them.

Good Lawd. That, right there, is the Rice experience. Slow off the snap. Quicker in second-gear than revving up in first. Doesn’t look open. Looks sluggish. Dunks on the corner. Big play.

Getting open can often look like hard work. Rice led the nation in targets and grabs last season, by a decent amount. But almost half of his catches were contested — Rice finished with a 48.5% contested catch rate, per PFF. Rice can be languid in his movements. Routes that should have some snap to them become elongated:

Sometimes, he looks bored with the process, with the details… or tired… or both. Just toss the ball to a spot where only I can go and get it and I’ll bring it down. He finished 2022 with a wince-inducing 8.3% drop rate last season — the majority of which were concentration drops rather than defenders dislodging him at the catch point. Rice had the largest route share of any receiver in the nation last year, playing in SMU’s turbo-charged offense. Perhaps on a more manageable diet, there’s an extra bounce in his step.

Some of his closest athletic comparisons, per Mockdraftable: Nate Burrelson; Brandon Ayiuk; Davante Adams. That feels right, save for Adams. Ayiuk has developed into a true, line-him-up-anywhere, watch-him-get-open, one-on-one star, but he started his career as the ideal second foil whose skills fit within the framework of an offense, rather than him winning independently.

Maybe that’s Rice’s future. This receiver class features a number of 2’s and 3’s. And if you’re taking a #2 or a #3, it’s best to wait until rounds two or three. Rice might be limited, but he brings some upside. He averaged 14 yards per catch last season, despite lacking the top-end speed to be a true homerun threat or a genuine after-the-catch creator.

And he’s not just a vertical menace. Rice is excellent at teasing the threat of verticallity to cut underneath. He loves to sell the vertical stem before attacking back inside or returning to the ball:

So, we have a receiver who doesn’t get open a ton, and when he does, he is prone to dropping the ball. But old habits die hard. There’s something there. Dropping prime Blake Griffin on an offense already blessed with electric speed is a nice change-up. Building out a receiving room with different body types and skill-sets is what teams are looking for; using Rice as a power-slot, someone who can press vertically from cut split and tight alignments fits with the league’s micro-trend.

Rice won’t be a number-one option at the next level. He won’t be a game-breaker. But he can be a reliable second or third option; someone whose game will be elevated by playing with a better quarterback.

The Chiefs have spent the majority of their receiver resources chasing speedsters. Rice adds a different dimension. Slot him next to the cadre of speedsters and Rice starts to look like a nice complimentary piece.

The floor may be limited, but Rice has a particular skill you cannot teach: He can jump over the back of defenders, he can leap in traffic, he can rejig his body while in flight, and he locates the ball. Can’t you just picture him making a leap-over-the-back play in Arrowhead in January?

In certain spots, I thought Rice would flush out of the league. He just doesn’t have the twitch required to be a consistent underneath threat. But with Patrick Mahomes and Andy Reid, he’s going to have a role. You can envision him striking up chemistry with Mahomes on vertical shots out of the slot. He won’t have to be the bedrock of the passing game, but he will provide an explosive downfield presence.

56. TRADE: Chicago Bears: Tyrique Stevenson, CB, Miami

Where do the Bears want to play Stevenson?

At Miami, he was a pure bump-and-run corner. Ask him to do anything else, to sag off in zones, to relate to routes from off-coverage, and he struggled. He either looked lost, disengaged, or a beat behind the play. As a tackler, his effort ebbed and flowed. There were times when he was engaged, and other where he had no interest in the physical side of the game.

That doesn’t really fit the Matt Eberflus model. Eberflus utilizes zone coverages more than any coach in the NFL. He wants tough tacklers at corner, and guys with great instincts. His defense sinks to depth and then rallies. Corners have to arrive at the catch point early and with tenacity.

That’s not Stevenson. He’s played a little in the slot, which could make some sense.

Some teams viewed him as a potential safety convert. Stevenson isn’t aggressive in the run fit but he is aggressive when attacking the ball in flight. From the safety spot, he’d be given more a freer reign to play see-ball-get-ball football from deep. That could work. He’s got long limbs and good straight-line speed.

But it’s a clunky fit. Stevenson’s best fit is as a boundary, press and run corner. All NFL defenses need corner who can hang in man-free coverage for 30-40% of snaps. But Eberflus’ is on the lowest plausible end of that spectrum. Stevenson could be a nice piece for those snaps. Or he might be indicative of a shift in how Eberflus wants to set up. If it’s the traditional Eberflus blueprint, though, Stevenson feels miscast.

57. New York Giants: Jon Michael Schmitz, IOL, Minnesota

What a start to the draft for the Giants. Deonte Banks and Jon Michael Schmitz were absolute steals and fill massive holes on the roster. It’s always nice when you get to be honest about taking ‘the best player available’ who just so happens to match up with your needs.

Schmitz will be a plug-and-play starter at center. He is a 6-4 jar of polish. Schmitz is an in-your-jersey mauler who blasts fools who dare to cramp his office space off the ball. At 24 years old, he’s older than most prospects – and that’s a knock that will see him wiped off some draft boards. But given that this isn’t a class chock full of center talent (unless you want to move some of the guards, as teams probably should) it’s a slight demerit rather than a fatal flaw.

Schmitz is a fairly one-dimensional prospect in the run game but holy hell has he mastered that dimension: He’s a kick-and-go, outside-zone runner who is rarely, if ever, dislodged from his spot and who can put a dent in the defensive front. Schmitz is a wizard at the nuances needed along the interior. He makes the most difficult block – the reach block – look easy; the reach block typically defines the success of an outside-zone run. It’s rare to find a center who is so fluid and controlled in their movements as a reach blocker who can also pummel people back with raw, unadulterated power if that’s what’s needed.

Hat. Feet. Hands. Those are the keys to being a successful outside-zone blocker, and Schmitz is the finest hat-hands-feet blocker in the class. He is always in-sync. The only time he really gets in trouble is when defenders flow from depth and undercut blocks; he doesn’t quite have the twitch to be able to react to linebackers descending — an issue that shows up when defenders try to undercut double-and-climb situations, too.

That’s the only real concern: lateral quicks. Schmitz doesn’t have the hops to pull and move across the formation, which limits the scope of where he can land in the draft. As teams look to embrace the power-spread, they’re looking to build out an offensive line where all five guys can pull and move in space. Finding a Jason Kelce or Creed Humphrey is like landing a unicorn, but that’s now the requirement for teams looking to build a smashmouth-spread offense.

Schmitz is not that. He’s more old-school. He can turn and crease on quick guard-center exchanges, but he doesn’t have the off-the-snap juice to pull to the perimeter.

In pass pro, Schmitz is always on. He’s quick to scan and reset against any kind of pressure or twist. His eyes are fast; his feet are quick enough given his frame. Again, he wins with his hands. In one-on-ones in Mobile for the Senior Bowl, Schmitz was like Dr. Octopus.

Pass-rushers arrived from all angles with every conceivable move. Whichever way they moved, there was Schmitz chucking out an arm and snagging the defender in his mitts. He stuns rushers early in the rep and then has the smarts and technical skill to latch on and ride out the rep.

Schmitz has enough bulk to move to guard full-time if needed. But given his understanding of fronts and protections, it’s best to keep him at center where he can have an impact on the game before the snap.

58. Dallas Cowboys: Luke Schoonmaker, TE, Michigan

The Cowboys clearly think of the tight end position the way that the rest of the league thinks of running backs: They them as interchangeable; they like a certain skill-set; they’re going to target one every year; they’re not going to pay a second contract.

Taking a tight end here made sense. It’s a loaded class. And if you didn’t try to land one early, they’d be off the board. Between 2020-2022, only four tight ends were selected in the first or second rounds. This year alone, there were five taken in rounds one and two.

The position made sense. The player? I’m unsure. I think there’s some helmet scouting going on with Schoonmaker. He’s an explosive, athletic player who is extremely sudden once out in the route. He’s a good, vertical seam runner. And there’s enough snap in his hips that he can cause problems at the intermediate level – and he’s flashed as a playmaker after the catch.

That’s the good. The issues: Blocking. Schoonmaker is more of a move blocker than an in-line guy. By virtue of the wings on his helmet and the traditional tight ends that come out of that school, you’ll hear about him being a bruiser at the point of attack. I don’t see it. He doesn’t move anyone off the ball. His technique is suspect: he likes to toss his arms out, latch on, and then allow his feet to catch up. He’s rarely in sync.

Those points are correctable. The athletic upside is clear, and is what will have the Cowboys excited. But there were more refined options who better fit the Cowboys’ needs at this point in the draft. He’s also an older player. By the time the season rolls around, he will be 25-years-old.

Taking an older prospect at one of the most mentally taxing positions in the game who is, essentially, a glorified seam runner is no bueno for me.

59: Buffalo Bills: O’Cyrus Torrence, IOL, Buffalo Bills

Torrence was the number #MyGuy in this class. He was the 11th overall player on my board and the top interior lineman. At 59, the Bills not only fill a need, but they do so at tremendous value.

Torrence is a complete, all-around player. He played center at Louisiana-Lafayette (where he was responsible for setting protections and adjusting the blocking mechanisms vs. fronts) before moving to guard and then transferring to Florida. All the intel out of the staff he worked with him in both spots is that he’s ranges somewhere between Allen Turing and Will Hunting on the genius-ometer. Once he’s seen a front, structure or pressure path once, he’s got it banked.

Torrence is a craftsman in bully's clothing. He has the measurables and the feel of a pound-them-into-the-ground interior lineman. And that’s true – the torque off the ball is there (#54).

But Torrence is so much more than that. He has worked to refine issues within his game; he spent the past year working on the usage of his off-hand in the run game, and how to block to the running concept rather than just womping defenders for fun, as he outlined in a conversation with Brandon Thorn on Trench Warfare.

Torrence sits at the neat intersection where a genius athlete devotes themselves to mastery of the art rather than floating by on their physical prowess — only he has all the physical tools to execute whatever the hell he likes. Twisting and contorting a lineman, using length to stun then turn defenders, can be as effective as sending them to mars, depending on the concept called.

Torrence knows how to use his combination of snap speed and length to fracture the line of scrimmage without only driving dudes back.

The in-line brutality still exists. Unlike a lot of this year's class, who shine when they skip step or wrap around, Torrence creates a vertical surge at the point of attack.