Pick by Pick Analysis of the third-round of the NFL Draft

The players, the scheme fits, the value

Day Two, the cliché goes, is when a team builds out the core of its roster. The value in this draft was from the top of the second-round through to the middle of the third. Let’s dig through the most intriguing picks, players, and scheme fits from the third-round.

NFL Draft Hub:

Pick-by-pick analysis, the first-round: Picks 1-10; 11-20; 21-31

Home & Home Podcast: Breaking Down Day One

Pick-by-pick analysis, the second-round

Home & Home Podcast: Breaking Down Day Two

Pick-by-pick analysis, the third-round

64. Chicago Bears: Zacch Pickens, DL, South Carolina

The Bears clearly have a formula. They’re betting on high-upside guys with traits along the interior. They selected Gervon Dexter in the second-round, a flawed yet fascinating interior prospect. Pickens falls in the same category.

Pickens is an ultra-explosive, jump-off-the-ball prospect. When lined up as a three-tech, one-on-one against guards on an island, there are times when he is unblockable. He’s a fluid mover with long arms, allowing him to play keep-away with squatter linemen.

Reinforcing the interior was a major need for Chicago this offseason. Matt Eberflus’ passive defense relies on a four-man rush running tons of games up front. They’re not going to run a battery of pressures or creative blitzes. It’s going to be four-down and go – for the most part. Such a setup requires leapers inside. In Pickens and Dexter, they landed a pair of agile rushers who fit the bill.

The concern: both are technically raw. If they don’t win off the snap, they’re in trouble. Both have been bullied in the run game. They’re rotational pass-rush pieces – with Dexter having a tick more upside as an every-down defender. Given the Bears’ depth chart, they’ll both be likely to play a bunch of snaps in year one. That’s great for their development, but it’s a concern for the Bears’ ability to control the line of scrimmage down in and down out.

65. Philadelphia Eagles: Tyler Steen, OT, Alabama

This smacks of the Eagles thinking a year ahead. They announced Steen as a guard but he can fill in as a swing OT (replacing Andre Dillard) or compete for the open right guard spot. Right now, that spot belongs to Cam Jurgens, who the Eagles drafted to be the long-term replacement for Jason Kelce at center.

Getting a year ahead at a position that takes two to three years to develop is a smart strategy. By the time 2024 rolls around, the Eagles should be able to roll Jurgens to center and slot Steen in as the starter at guard. If he gets on the field early in 2023, he will have earned it.

Steen is a bruiser off the ball. But he isn’t the fleetest of foot, hence why teams viewed him as a guard. His redirect is poor. His footwork can be plodding. He gets up off the ball too upright. Some of that stuff is technical, and there’s no better place to iron out technical concerns than Jeff Stoutland U.

66. Philadelphia Eagles: Sidney Brown, DB, Illinois

How can you not love this selection? Brown might wind up being too small for the league. He could end up

How you had the two Illinois safeties graded out compared to one another came down to scheme fit and personal taste. Quan Martin was more of a slot corner in school who filled in on the back end against certain personnel groupings, with the potential to move back full-time. Brown was a roaming, snarling, what-are-we-waiting-for, firecracker who played down in the box.

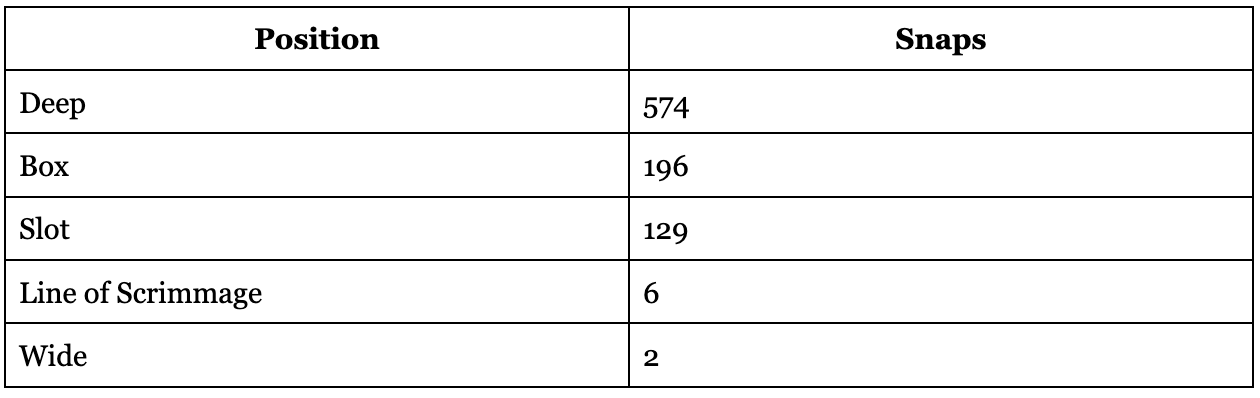

Brown wants to play down near the line of scrimmage. Some safeties like hanging out on the back end. They want to be ball-hawks, zipping from hashmark to hashmark or breaking on routes underneath. Not Brown. He wants to be part of the action. Push him close to the line of scrimmage, light the fuse, and watch him detonate:

Brown brings thunder to the point-of-attack. He is instinctive around the line of scrimmage:

That’s just filthy. Utter filth.

There is some Talanoa Hufanga to his game: he is so amped up, so keen to cover every blade of grass and deliver every blow that he can play out of control. There are concerns in space, too. Brown is better driving downhill than he is working backward.

Where and how he gets on the field is a question. He lacks the size to match up with tight ends or receivers who move closer to the LOS. His best shot might be in three-safety sets, where he can push closer to the line of scrimmage as a pseudo-linebacker or sink into the robber role in the middle of the trio. There, he would have some protection behind but while being free to play see-ball-get-ball football from centerfield while also being able to fit up against the run.

67. Denver Broncos: Drew Sanders, LB, Arkansas

I was surprised the league wound up being this low on Sanders, frankly. He was the third linebacker on my board – though as I’ve noted many times before, ranking all linebackers as a collective is folly. The assignments from team-to-team are changing at an ever-increasing rate. What the Jags need at linebacker is different from what the Patriots are looking for.

That said, what every team needs: malleability, explosiveness, length. No matter your scheme, those traits have a place. And that’s what Sanders has in abundance. He’s a former edge defender with one season of off-ball experience – and it shows. But I really, really thought a team would bite on the upside of what he could be: A Kyle Van Noy-ish part-time edge, part-time off-ball guy, and a ravenous blitzer.

Not quite. Sanders had to wait to early in the third-round to hear his name called, but he wound up landing in an ideal spot.

Sanders moves with shocking lateral quickness and fluidity for someone of his size and build.

Sanders was mostly a north-south player at Arkansas. He was typically used on base downs as the team’s ‘early plugger’, with the linebacker fast-fitting versus the run to build a four-man front at the snap out of the Razorbacks’ base three-down structure (#42):

His job requirements in the league will be different. There is plenty of fast-fitting in the NFL these days, but to play on that vertical plane only makes a linebacker one-dimensional, no matter their build or innate athleticism.

Sanders has to prove he can comfortably move out in space. The see-ball-get-ball, downhill stuff, attacking the ball, he’s got that down. The two-way-goes, the searching-and-finding, the zigging this way before having to jut back the other, that’s where Sanders must adapt and evolve.

The athleticism is evident. But the feel is yet to be tested. Sanders’ drop-and-find instincts are lacking.

He isn’t a high-level diagnose-and-attack player. He’s a quality team-construct defender, one who slots into what is asked of him and looks to bring thunder to the point-of-attack.

That ebbs and flows. His burst allows him to beat linemen to their spot. But he doesn’t play with great balance or functional, in-line strength. Sanders was consistently blasted by pullers and wrappers — despite arriving at the right spots early.

When his first step is downhill, Sanders plays with shocking mobility. He has great burst and lateral quickness when flowing down to the ball.

He is not, however, a true-blue thumper. Sanders wins by arriving early and undercutting blocks. He isn’t interested in the hand fight or delivering thunder. When asked to play north-south, to hit his mark, he delivered. Against zone-centric concepts, he thrived. When asked to wiggle and move and then attack vs. gap-scheme concepts or pulling linemen, he struggled.

When the ball is pushed into space, though, when asked to first work to cover and then enter attack mode, Sanders is in real trouble. There is a delay in his thought process in coverage.

Receivers fly past him. He fails to pick up dudes in zone coverage:

He misses a ton of tackles:

Sanders whiffed on 22 tackles in 2022 alone. The athletic tools to arrive to the ball are, the instincts when he does are lacking.

He isn’t a great reactionary defender. That’s the issue. If he’s forced off his initial impulse, he gets into trouble. If a receiver doesn’t waltz into his immediate area, he struggles to adapt.

Sanders’ run-game work is valuable. But what else can he offer versus the pass?

There are three options: A) Someone who can sink into coverage; B) someone who can bounce into multiple positions as a matchup piece; C) someone who can be a high-level pass-rusher, either as a blitzer from depth or sliding over to the edge.

Sanders has the body type to major in categories A or C.

Sanders was only a decent-ish blitzer in college. He got by on hops and in-out agility. If he stole a march on a blocker, he could slip into the backfield before they blinked. If not, Sanders had little else to offer. He doesn’t (yet) convert speed-to-power; he arrives at the point-of-attack without a plan. It’s speed or nothing.

When given a free pathway, he has the juice to punish an offense.

But there’s work to be done as a pass-rusher if a team wants to kick him to the edge on occasion or feature him in their pressure plan. The raw tools are there. But that’s all they are at this stage: tools.

Things are just as up and down in coverage. Sanders doesn’t have the natural feel of a drop-and-find zone defender. He has antsy eyes — similar to Henley. He wants to know where he’s going and race to ASA-and-P. It doesn’t always work that way.

Plus, he can slow and cumbersome moving back in space, belying the athlete we know he is and that he shows when working top-down. Everyone is quicker moving forwards than backward. But in an age where defenses are mugging linebackers constantly, Sanders has to get much, much better. A lot of his perceived value at the next level will be that with his body type and explosives, he can be an effective mugging ‘backer. But to do so, a mugger cannot just be a decent blitzer. They have to be able to drop to depth quickly, with alert eyes. And then they have to be able to transition from hitting that landmark back to driving downhill.

If you’re totting up the non-negotiables for a linebacker in the NFL, that’s at the top of the list. You don’t have to zoom sideline-to-sideline. You have to be a through-the-crevices phantom. However, being able to drop from a mugged alignment and then flow back down from coverage is a must.

Any team selecting Sanders will have known things will start out clunky. There’s going to be a learning curve. But the tools for him to develop into a Tremaine Edmunds/Rolando McClain type are there — an off-the-ball playmaker who does damage downhill and in clogging passing lanes. The only real concern with that role: Sanders has below-average arm length for a linebacker compared to Edmunds and McClain, both of whom have bailed out iffy coverage habits by being able to chuck up a go-go gadget arm to disrupt passing lanes.

For Sanders, there’s no better landing spot than Denver. The Broncos already have a solid linebacker room. Meaning: He won’t be forced on the field too early. And that will suit his game. Where he’s at right now, he should be a pressure package player, someone used in specific situations, where he can use his skills as a blitzer and offer some size as a dropper on zone-pressures to mask passing lanes. That fits with Vance Joseph.

Joseph is the closest thing defensive football has to mad scientist. He doesn’t care for all your talk of rotations and two-become-one-style defenses on the back end. This Fangio world? Sure, he’ll dabble in it – he’s no fool. But at heart, he wants to fend fire after the quarterback. In his three seasons as the Cardinals DC, Joseph averaged a 36.3% blitz rate, comfortably the fattest mark in the league over that span:

2022: 34.5%

2021: 35.2%

2020: 39.4%

And those figures don’t account for zone-pressures — one player on the line of scrimmage dropping out; a player from off the ball pressuring — which have increasingly become the bedrock of Joseph’s defense in obvious passing situations.

Joseph is as creative and imaginative a blitz path designer as we have. Having a downhill, can-shuffle-to-the-edge weapon like Sanders on his defense will surely get the wheels turning. Joseph worked with a bundle of flex pieces in Arizona. Isaiah Simmons and Zaven Collins were the standouts, prospects dubbed as ‘positionless’ who turned out to be players who had no position.

Joseph did good work amid the mess that was the Cardinals roster building plan on defense. He never could find a role that worked for the bounty of athletes who lacked the skills to lineup in one spot. But he found deft ways to deploy those guys in semi-effective ways on a package-by-package basis.

Having one of those guys is fun. Two, at a push, can work, provided they’re sat at different levels of the defense. Working with four or five, when you know you have to play them… that’s tough.

Joseph did an admirable job, regardless of the reputation of the Cardinals’ defense over the past couple of years. He did good work amid an organization self-sabotaging its defense. How those years inform his time in Denver will be interesting. He’s immediately working with a much stronger group. By adding Sanders, the Broncos will be hoping that Joseph can build on all the work Ejiro Evero did last season: adding more disguise and creativity to the team’s pressure packages. Sanders will feature heavily as a flex piece while he continues to develop as a functional off-ball ‘backer.

68. Detroit Lions: Hendon Hooker, QB, Tennessee

Talk that Hooker would go in the first-round felt overblown throughout the process. It was narrative season, and latching onto the nice, smart quarterback with a great story was always going to lead to pre-draft inflation.

Hooker was a third-round prospect on tape and by profile. Nabbing him in the third represents good value for the Lions. Taking a quarterback every year should be a golden principle every single year for every single franchise. You just never know.

The Lions opted to sit out the race for the top QBs this year. They passed on Will Levis and Hooker in the second-round, opting to stick to their board and the long-term process that Brad Holmes and Dan Campell have been banging the drum for two years.

But taking a flyer on Hooker in the third makes a ton of sense.

Hooker is a smart, efficient quarterback. He’s the kind of competitionaholic QB who has worked relentlessly to improve every facet of his game; his load-to-release time is quick and smooth, and improved year-on-year. He does all the little things that add up to wins, and he has enough playmaking chops to get any team excited. His work ethic also just so happens to make him a beloved figure among both players and coaches.

The issues: He is 25-years-old; he played in Josh Heupel’s nonsense, pump-and-dump offense, one with little to no transitive properties to the NFL.

That’s not a knock on Heupel, by the way. If I was running a college program, I’d also embrace a pace-and-space offense with exaggerated receiver splits, and a heavy dose of RPOs. I’d modulate tempos — running from warp speed to slow-mo. And I’d also feature only a handful of concepts dressed up in an equally slender number of ways — most of them being of the you-go-there-I-go-there, one-read-and-go variety. That’s good offense; its impact, everywhere Heupel has been, has been immediate and profound.

Some offenses are expansive. Even if they have foundational components, they’re liable to unfurl one or two new wrinkles every week. Heupel doesn’t work like that. His core philosophy and the crucial concepts have been stress tested… and he runs them… and runs them… and runs them some more.

In some senses, gimmick-laden approach. But it’s hard to argue with the gaudy results.

What is inarguable: It’s not a system that prepares a quarterback for the next level. There were subtle alterations for Hooker — given his experience and skill level — compared to contemporaries who’ve played in Heupel’s system at the college level. Those tweaks pushed the Hooker-Tennessee version a tick closer to the real offense world than the bullshit one Heupel has run in the past. Back in his days with Missouri, Heupel used ‘sleeper’ receivers. In essence, one side of the field one did not run routes. The other side would. The defense would drop into coverage, expending energy on every snap. Missouri would target only one side of the field, with those receivers running routes. They would then zoom to the line of scrimmage and target the other side of the field, where the receivers had just been resting. Often, they’d run the exact same concept back-to-back on either side of the field, with the defense trying to keep up with the pace — and to figure out which side of the field housed the sleeper cell.

As pure offense goes, it was nonsense. But it was damn effective. It turned Drew Lock from a bad quarterback with a big arm into a bad quarterback who was selected 42nd overall by the Broncos — and who, stunningly, went on to be wholly unprepared for the pros.

Heupel’s offense isn’t so aesthetically egregious (and strategically ingenious) these days. There are pro concepts within his structure super-spread, split-the-field in half structure. There are pro-throwing windows — and Hooker has shown he can hit them. But it’s still a long, long, long way, in terms of style, communication, and the demands placed on the quarterback both within the working week and on game day.

It’s not just the RPO, funky play-action designs, either. Everybody runs some version of that these days; it’s just about how far an offense tips along the spectrum. And Hooker has flashed when asked to bounce out of that stuff and to go create some opportunities all on his own. But it’s the design of the offense taken in conjunction with what it asks of the quarterback. Setting projections; adjusting to different concepts week-to-week; working through full-field progressions; the pre-to-post-snap ID process. Even within some super-spread offenses, that stuff is baked in. In Heupel’s world, that’s fluff. The majority is controlled by the staff on the sideline. Reads are predefined. And there’s little change in gameplan-to-gameplan that once a quarterback has mastered the 15 core concepts, they can enter into pre-to-post autopilot mode.

Given the gulf between the Tennessee offense and what’s asked of a quarterback in even the most basic NFL offense, there will be a steep learning curve for Hooker. A team has to decide whether that investment is worth it for a player who could be 27-years-old by the time the light turns on, and who will be pushing up against 30 by the end of his rookie deal.

And then there are the footwork issues: Hooker has not been asked to play in a rhythm or timing-based offense, one where his footwork matches up with the routes of receivers. It’s a see-it-throw-it offense. You catch the ball in the gun, rock back, and wait for receivers to uncover. The best quarterback’s within that system operate well because they have tremendous field vision. Hooker checks that box. But when moving up to the next level they’re forced into a different world entirely – matching their steps to the timing of the concept (not a tick late; not a tick early); turning their back to the defense on turn-the-back play-action; rolling out on boot concepts.

It may bump up against hyperbole, but that Heupel-Baylor-Super-Spread model is encroaching on a different sport entirely – at least for the quarterback.

I like Hooker. His growth is a great story. Were he a plug-and-play, ready-to-go starter, his age wouldn’t be quite the same factor. But with how far he will have to transition from HeupelBall to Pro Football, it is.

Taking him late on Day One was always a non-starter. But doing it on Day Two? That’s a smart call. The Lions have a smart coaching staff and an outstanding collection of weapons, which should at least soften the learning curve. He can sit and wait behind Jared Goff for a season as he transitions from HeupelBall to real football. If the Lions strike gold, they’ll be set up for a Russell Wilson-Seattle-type run. If not, they will have a competent, smart backup who can move and create plays with his legs. For the price of a third-rounder, that’s a gamble worth taking.

There was a different path for the Lions. If you scan their draft haul, it’s impressive. Forget, for now, the positional value or where they took those players – if you want, you can jockey some of the selections in your mind to make them more palatable (swapping Brian Branch to the first for Jack Campbell in the second, for instance):

R1, P12: Jahmyr Gibbs, RB, Alabama

R1, P18: Jack Campbell, LB, Iowa

R2, P3: Sam LaPorta, TE, Iowa

R2, P14: Brian Branch, DB, Alabama

R2, P5: Hendon Hooker, QB, Tennessee

Taking a swing on Hooker makes sense after addressing needs and continuing to build out the depth of the roster. I really, really like what they executed this week.

But I have a gnawing feeling in the back of my mind. The NFC stinks. The quarterback situation is dire. After Jalen Hurts, Dak Prescott, and Kirk Cousins, the conference’s quarterback rooms are populated by a sea of unknowns or well-known, mediocre QBs. Aaron Rodgers just left the division. It’s right there for the taking for the Lions.

In that context, taking a big, big swing on one of the rookie QBs would have made sense. As is, they have a compelling roster that’s still a couple of notches below the Niners and Eagles. They’re probably in the middle strand of second-tier teams. That’s great! Good job. But building from the middle is hard – and as the Lions improve their access to finding a quarterback who can hang in the postseason with the Niners, Eagles, and whoever comes out of the AFC cage match will be limited.

Maybe they feel they can go and hunt for a quarterback next offseason – there is always next year’s draft, folks! And it’s always better than this one, don’t you know. But isn’t the plan to win and win big this year? If they compete for the NFC North, as they should, moving up to select a quarterback next year is going to be awfully costly. Unless they can swing a trade for a wantaway star – and it’s tough to see

They’ve set their team up with an outstanding foundation. They look explosive on offense. On defense, they have versatility on the back end and dynamism up front. This should be a good team; it will certainly be a fun team. How they’ve built their team, is almost the clichéd version of how you should build a team. Except for one piece, the most important piece: The quarterback.

I’m bullish on the Lions short, medium, and long-term. But there’s still a nagging sense that they missed a window this offseason to do something that could have addressed long-term concerns at quarterback — before the price starts to eat into the future. What if they did everything right on this path but they chose the wrong path from the outset?

69. Houston Texans: Tank Dell, WR, Houston

70. Las Vegas Raiders: Byron Young, DL, Alabama

71. New Orleans Saints: Kendre Miller, RB, TCU

72. Arizona Cardinals: Garrett Williams, CB, Syracuse

73. New York Giants: Jaylin Hyatt, WR, Tennessee

Hyatt is an absolute flyer with elite top-end speed. If you miss him, or lose him, or he wins off the line, it’s a house call. But there are concerns about how well-rounded he is as a receiver. He ran the slimmest route tree of any of the receivers slated to go near the top of the draft. It was all gos from the slot, slants, and screens.

He’s more of a north-south runner than someone who can create separation throughout the route. He is an explosive chess piece within the concept, not someone who — speed aside — will create a ton of separation.

Tennesse’s offense, as noted earlier, mimics the Baylor offenses of old. Remember those? They spat out explosive receivers every year, receivers with gaudy numbers and blazing speed who would surely succeed in the NFL, right? *tumbleweed*

Through the structure of the Vols offense, Hyatt was afforded an unfathomable amount of free access release – meaning he could get off the line of scrimmage without any defender challenging him. And in that world, he cooked. As a second-reaction route runner, he was sloppy It’s A-to-B. If it’s about getting vertical, that’s fine. If it’s a comeback or out or dig, everything is elongated.

If you were selecting that in the first-round, that would be a concern. But in the third? Sign me up!

This is a tremendous fit for Hyatt. Brian Daboll and his staff are complete shape-shifters. They will change their offense, radically, week-to-week and season-to-season. Unlike others who speak in soundbites, he really, genuinely, fits the offense to his team rather than squeezing players into his overriding philosophy.

Daboll’s staff was also the finest group and manipulating space last year. Through formations, motions, shifts and the usage of Saquon Barkley, they found creative ways to stretch the defense in one way before puncturing it in the vacated spots. It’s less of a timing-based structure. It’s this: We’re going to bend the defense this way. If it reacts as we expect, the space will be here. Hey, Daniel. At the snap, check we’re correct. If we are, then toss it to the open man.

In that world, Hyatt will be a real asset — both in pushing back the coverage, creating voids and making plays in space. Hyatt is a fairly one-dimensional player, but this is an A+ fit.

74. Cleveland Browns: Cedric Tillman, WR, Tennessee

I had Tillman graded ahead of Hyatt for a couple of reasons, despite the pair playing in the same offense. Tillman is a big target, and he’s capable of contorting once up in the air to locate and track shots down the field; he has a good sense for modulating the tempo of his routes to create openings late in the rep, a necessity when you’re playing on the outside of the formation.

But Tillman and Hyatt share one crucial feature: They’re smart. The same reason the Tennessee offense makes it tough to envision how a quarterback can translate from that system to the pros is what intrigues me about the two receivers.

Tennesse’s super-spread is built on choice routes. Back in the Baylor days, these were novel. Now, they’re ubiquitous. Those Alabama receivers that the school has churned out in the first round? A bunch of their success was built on the same route concepts, deep-breaking options that ask a receiver to drive downfield and then attack daylight. In essence, the routes are less constructed, and therefore less replicable. It’s about receivers reading and reacting on the fly: to the leverage of the defender, to the defensive shell, to their teammates to the space around them.

It’s the same concept that Sean McVay instituted to such success early in his days with the Rams. Sure, in the pros, there are landmarks. There’s timing. But on shot plays, McVay handed over freedom. And not merely in the two-way-go, typical option route way (which is built into almost all route concepts, depending on whether it’s middle-of-the-field open or middle-of-the-field closed coverage) but true freedom. Get downfield and run to grass.

When it’s humming, it’s unstoppable. The same play call can look different. It’s a nightmare for the team to study and advance scout for, to get any sense of tendency based on the formation or the alignment of the receivers or the early phase of the route combination. If you have good players, like the Rams and those Alabama sides, then those great players can just run away from lesser players. For the quarterback, they get to sit back and play see-it-throw-it football, without necessarily worrying about the timing of the concept.

Great! For QBs, that it’s a knock. But how is having receivers who can think so quickly, so instinctively on the fly a bad thing? The league is full of offenses running similar deeper-breaking options these days. Being able to read and react to the defense, the coverage shell, and where the space is on the field is a huge asset. It takes an unusual 3D mapping of the ever-evolving geometry of the field and the athletic chops to punish a defense once you spy that space. Tillman has both in abundance.

75. Atlanta Falcons: Zach Harrison, Edge, Ohio State

76. New England Patriots: Marte Mapu, LB, Sacramento State

77. Los Angeles Rams: Byron Young, Edge, Tennessee

The Rams needed this draft to reset their roster. They had to get younger. They had to get quicker. Young ticks one box – though I guess he is younger than a ten-year vet.

As I noted pre-draft, most outside evaluators had a fourth or fifth-round grade on Young, but the league was much higher on the Tennessee edge-rusher.

Young is a fire-breathing, turbo-charged edge-rusher. He is all gas, no break. He’s a leaper, one with little feel for the nuances of pass-rushing – and lacking the ideal measurables to cover up for that fact. He’s a super torqued-up rusher with a motor that runs for days. At the combine, he posted the second-quickest ten-yard split of any of the edge-rushing prospects, behind only Nolan Smith. He finished third among all edge defenders in Next Gen Stat’s combined athleticism score. But Young isn’t just a tester; he’s a functional athlete. Tennessee moved him around the formation: He played as a heavy-five in three-down fronts. He dropped into coverage from the edge. Against Florida, Tennessee even used him as a middle-of-the-field rover, with him spying on Anthony Richardson.

At his best, though, he’s a stand-up, get-off-and-go edge-rusher. Anything else, at this stage, is asking way, way too much.

Young is an impressive character, though, and that’s what has teams excited. He came to the game late, but he closed his career at Tennessee as a captain. He lacks all of the opening phase, contact phase, or the closing phase might of the top-tier edges in this class, but he comes pretty damn close if you’re just talking about the first step. Young’s get-off can match anyone's (#6):

He wants to be great – and he works at it. And even when his technique fails him (which is often) he fights and scratches and claws his way through reps. His energy never flags. He is as explosive and tenacious during the final rep of the game as he is during the first. Throughout the rep, whether versus the run or pass, Young never, ever stops working.

That matters. Coaches and scouts are willing to embrace a raw prospect who shows a willingness to effort through work on and off the field.

There are three issues, though: Young is 25-years-old; he has short arms; he has no idea what he’s doing. That last one may seem harsh, but it is also, unfortunately, a fact. Of any of the Day One or Day Two rushers, Young’s hands and feet are the most out of sync – and this is a class that includes Tyree Wilson, people!

Why does that matter? Because it makes a pass-rusher inefficient. It adds extra steps to their rush. It saps an edge-defender of the pop needed at the point-of-attack. It can make a rusher unbalanced, making harder to hit a linemen with the necessary move, or to set up one way before swooping the other.

Watch:

He consistently slows his feet on contact. Rather than charging into and through blockers, his feet get tangled. He stops. He engages. And then he tries to push ahead.

Rather than moving in one seamless motion, Young’s rushes come in fits and starts. There’s an initial surge… and then a break… and then a second surge. He is a poor habit of gaining an advantage, of building a runway to the linemen, of creating a lane and angle to convert speed to power, before slowing his feet, losing momentum, and having to generate up a second surge.

Young likes to slow play early in the rep, to bait tackles into a sense of comfort before exploding. That belies his off-the-snap juice, and often leads to a dud rep.

Starting again from a standing start without a runway limits the ability for a pass-rusher to create any oomph at the point-of-attack. Too often, if Young cannot dip-and-rip around the corner, he’s stuck in no man’s land. If he’s able to generate any movement at the point-of-attack, he’s an all-corner-all-the-time kind of rusher – and those are not only easier to stop but they’ve also been phased out of then league.

Coaches believe they can correct this stuff. Feet. Hips. Hands. Hat. Those four things are, largely, technical flaws that coaches can work through. Correct the feet, the theory goes, and the rest will follow in order. It’s why scouts are so high on Tyree Wilson, a player who suffers with the same issues as Young (inefficient movement; false steps; slowing his feet on contact).

There are reps with Young when you see the potential. The times where he does sync up his feet, lower half, and hands, you see enough pop to raise your eyebrows. You know, maybe this could be *something*.

That’s what the Rams will be hoping for. If Eric Henderson, the team’s defensive line coach and one of the finest position coaches in the league, can clean up the issues in the first phase of the rush, then it will naturally boost the all-important second-phase: the contact phase.

Young has shown that bending around the edge and closing to the quarterback comes naturally, if he’s able to gain enough of an advantage. He has outstanding short-area quicks and closing speed:

But those second-phase wins are so infrequent or time-consuming or energy and speed-sapping that there just aren’t a ton of clean, get-off-and-go, dip-and-win rep on tape for someone with his natural skill-set. Too often, he arrives to the party ready to play clean-up duty. Where were you when the canapes were being served, Byron?

The stats tell the story. Young doesn’t make enough plays given his skills: He finished 100th in hurries in 2023. But when he does get close, he closes: Young ranked 13th among pass-rushers in hits and 18th in sacks. Some of that ‘closing’ production was a product of Young getting fat against overmatched players. As the competition level grew, Young’s production fell. But is indicative of the player: The lack of technical understanding limits him (right now) on a per-rush basis, which is why the hurries are so low; but when it does all come together, by luck or design, he’s mighty effective and he creates negative plays.

His lack of length will limit him in the league, too. He’s a rotational rusher. He will play in rush-only sub-packages. Against the run, he’s all over the place.

Some have compared Young to a poor man’s Nolan Smith: A high-flier who lacks conventional size. That makes sense, but it’s harsh on Smith’s game. Smith is technically proficient and he’s a thumper in the run game. He finds creative ways to generate power at the point-of-attack even if he’s beaten to the punch by a lack of length.

That’s not the same for Young. It’s in the run game where his inexperience is most exposed. Bad hands with short arms is a recipe for disaster in the run game. Young doesn’t have the instincts or technical chops to hang in the run game. He gets walked off the ball:

There are times when he is completely lost – jumping out of gaps or winding up in the same gap as a teammate, vacating a hole for the offense.

Woof.

Taking a flyer on Young even in the third round could mean setting fire to a draft pick. He will be 25-years-old during his rookie year, and he has physical and mental limitations – one is profound in the run game, the other in the pass. The Rams staff will believe they can correct the pass-rushing issues – and if a player can be a useful rotational rusher versus the pass it doesn’t matter how they hang versus the run.

He has two of the most important unteachable traits for an edge-rusher: burst and bend. In most drafts, Young is probably a fourth or fifth-round flier. In this class, he was pushed into Day Two.

78. Green Bay Packers: Tucker Kraft, TE, South Dakota State

Two tight ends for the Packers in this class. Luke Musgrave, who the Packers took in the second-round, is more of a dynamic move piece: An explosive, receiver-first type. Kraft is more well-rounded. He can play on the line of scrimmage. He’s a wall, one who delights in uprooting edge-defenders. He can create a surge off the ball in-line. In the passing game, he’s quick off the line and effective in catch-and-run situations. He’s a work in progress as a route runner, but he’s shown a good feel for the position and how to use his frame to post up defenders down the field to create a lane for his quarterback, even if he isn’t creating much separation.

The Packers spent the draft getting even younger on offense, and ensuring that the skill-sets of all their offensive pieces overlap tidily:

QB – Jordan Love: 24

RB – Aaron Jones: 28

RB – AJ Dillon: 24

WR – Christian Watson: 23

WR – Romeo Doubs: 23

WR – Jayden Reed: 23

TE – Luke Musgrave: 22

TE – Tucker Kraft: 22

It’s a compelling if young group. We know about Love. And we know about the complimentary styles of the backfield. Adding Reed, a nuanced, intelligent, route-runner to the explosivity of Watson and the physicality of Doubs makes a ton of sense. And the two new tight ends have harmonious skill-sets.

Whether it’s good enough is an open question. The Packers are banking on all these guys hitting together, on the same timeline. Adding another couple of veterans before the start of training camp would be smart – in part to get some reliable pieces in the room; in part to help usher along the development of the young pups.

But as they enter this reset mode, Brian Gutenkunst has done a good job of keeping in mind the whole picture of the offense. It’s clear what they want the Matt LaFleur-Jordan Love offense to look like, and they’ve built an offense, whole-cloth, through the draft over the past two seasons to fit those needs.

Whatever your thoughts on Gutenkunst, probably the most polarizing GM in the league at this point, that’s good management. He has not assembled an ad hoc roster of parts; he’s built something to a vision.

79. Indianapolis Colts: Josh Downs, WR, North Carolina

How about this for a draft strategy: Take every freaky athlete possible… bank on the idea that they can play football… or that we can teach them.

The Colts – and the Panthers – were aggressive in targeting the most athletic players in the draft. Only one of their first nine selections fell below a 9 in Relative Athletic Score, per MathBomb. They had three players cross the 9.9 threshold and seven cross the 9.5 mark.

The lone player to fall below a 9? Josh Downs. And he wound up with an 8.99.

Downs is a small, nimble, explosive receiver. He plays quicker than he even tested, and he tested at an elite level. He’s quick shuttling in and out of breaks. But his main value comes down the field. Downs has a great sonar for tracking the flight of the ball down the field, despite his diminutive size. He will be an exhilarating all-over-the-formation piece for Shane Steichen. He might not be an every-down player early on, but the coach will craft some specific packages to take advantage of his skill-set.

80. Carolina Panthers: DJ Johnson, Edge, Oregon

81. Tennessee Titans: Tyjae Spears, RB, Tulane

82. Tampa Bay Buccaneers: YaYa Diaby, Edge, Louisville

83. Denver Broncos: Riley Moss, CB, Iowa

84. Miami Dolphins: Devon Achane, RB, Texas A&M

You have to love it. The Dolphins want all the fast dudes. Achane is a short, slender, pocket rocket. If he sees any daylight, he’s gone. He will not be any every-down, feature back. But he will bring burst to an offense that is prioritizing pace over all else.

The Dolphins have built a team to try to make it immune to drives. Why bother stringing together 12 play sequences when you can score in two?

(It’s wonderfully oxymoronic, and perhaps by design, that Tua Tagovailoa’s great strength is that he’s efficient. He is built to point guard his way down the field and sustain drives — but the Dolphins have built an offense where that talent is a nice bonus, but non-essential)

Achane fits that mold. He’s a home run hitter on the ground or releasing out of the backfield as a receiver.

85. Los Angeles Chargers: Daiyan Henley, LB, Washington State

This might be the top prospect-to-scheme fit in the draft. There may be some PTSD for Chargers fans. The team has tried undersized zoomers at linebacker throughout the Brandon Staley era. It hasn’t just failed; it’s been an unmitigated disaster.

Henley can break that trend. He was the x-factor among linebackers in this class. For defenses, like the Chargers, that want to defend out of 6-1 fronts and operate with a sift-then-find linebacker, he’s an ideal git. He is on the older side, which put some teams off from the outset of the process. He hasn’t been tabbed among the Big Three at the position for much of the process, but was a late riser. His athletic testing has been strong, pushing teams and evaluators back to the tape – and the tape is strong.

Henley is a former wide receiver who moves as well as anyone in space. But there is enough classic sift-and-find football to get even the fervent linebacking anoraks excited (#1):

Henley brings enough downhill thump to unnerve blockers. He is explosive when in attack model:

Henley isn’t the kind of linebacker who drifts through the fractures of the line, undercutting blocks to find the ball. He’s a hit-the-landmark sort of linebacker, built in the TJ Edwards mold. He’s not going to lock-on and jockey with linebackers. Asking him to serve as an early plugger who works, functionally, as an extra linemen (as many classic “Mike” linebackers are these days), and he’d be in trouble. That’s not his game.

Henley wants to attack space. Leave him as the stand-alone ‘one’ off-the-ball in 6-1 boxes or as the move piece in a 5-2 front, someone who can sit off the ball, read-and-react, or push to the edge, and now you’re cooking with gas. Henley is happy to toggle from central spots to the edge of the formation:

I think somewhere in Los Angeles Brandon Staley just felt a shiver and started smiling and he’s not sure why.

Among the top four linebackers, Henley has the strongest diagnose-and-attack instincts of the lot.

He is nimble for a thick guy. He doesn’t just have to play north-south. He might not slither through the line the way some of the best-of-the-best do, but once he sees daylight, he attacks it — and he closes.

He rarely misses tackles in space.

Henley brings the same torque to the blitz world. Again, he delights in flowing downhill. He doesn’t have the pass-rushing chops… yet. At this stage, he’s just a bundle of energy, an athlete chasing the quarterback. But he’s explosive and plays with good contact balance, which is a solid enough starting point.

In terms of what is asked of modern off-ball guys, Henley fits the bill. Some linebackers are playing in kooky defenses. But what Washington State asked of Henley aligns snuggly with what the vast majority of defenses would ask him to do at the next-level, at least those at the vanguard of defensive innovation.

He can flit between positions. He can stand up as a mugged linebacker and blitz or drop. He can sink into coverage and cut crossers. He can kick over to the edge, whether to present an extra, late body versus the run or to offer a supplementary rusher.

When dropping into coverage, he’s always alert to danger. He still moves and runs like a receiver. He’s been dubbed ‘twitchy’, which is true. There’s a suddenness to his game. But he’s smoother than your typical, twitchy, supped-up safety tape. There’s polish to his game, an ease of movement in space and coverage.

He’s clean in transition. And when he needs to dial it from 0-60 he gets there in a hurry. Pair that with the diagnose-and-attack instincts and you have yourself a spicy middle-of-the-field marauder.

There are issues. Henley’s eyes are always active in coverage.

Is he too active? Henley flutters his sightline so quickly it’s as though he’s anxious, worried that if he doesn’t move his head at 5,000 MPHs he might miss something. His instincts are strong; he routinely gets his eyes to the right spots.

But the nervous, I-need-to-cover-every-blade-of-grass-on-my-own-energy, leads to sloppy mistakes. He bites on fakes and double moves. He drives one way to go make a play, while the assignment he should have been covering goes the other. The eagerness to do everything at all times leads to explosives landing in his spot. He needs to play with more patience, to play within the structure of the defense, and to trust the players and scheme around him.

And that’s what’s exciting. The area where he’s sloppy is the area that should naturally be his strongest. Moving in space, seeing the ball in coverage, and then finding? I mean this guy was a receiver! That stuff should come easily.

Dropping, scanning and cutting crossers is among the most essential skills of a coverage ‘backer these days. Henley has shown promise; he needs to find consistency.

As a Day Two pick, that’s worth gambling on. He has long limbs and plays with a kind of simmering ferocity that all of the top linebackers bring to the field. His profile suggests someone with one skill set, but his game is different. He’s mastered some of the trickier subtleties of the position, which will allow a team to feel comfortable lining him up from day one as he works on some of the coverage constraints.

At worst, the Chargers are getting a malleable, eager, frenzied linebacker with long arms who can sag into zones and clog passing lanes. Maybe he busts an assignment or two. But with what else he brings to the table, he more than makes up for it. And given what they’ve had off the ball in recent years, that will probably make the building tingly with excitement.

86. Baltimore Ravens: Trenton Simpson, LB, Clemson

Here’s the thing with Simpson: All the athletic measurables are there. Through athletic profile alone, he matches up with exactly what the league wants from its off-ball ‘backers these days. But his instincts, his feel for the position, are lacking.

Simpson has the most prototypical frame of any of the top guys. He profiles as a guy who can toggle between positions: He’s lined up as an overhang defender (which adds a touch of the Quay Walker to his profile), as an off-ball guy, and stood on the edge. Simpson always feels like he’s a tick late to everything.

Still: the third-round represents good value for someone of that profile. The Ravens have a decision looming on Patrick Queen’s fifth-year option, an option they are unlikely to pick up. They’ve already handed Roquon Smith the bag, so they’re looking for a different style of linebacker.

I wonder where Simpson will align in the early goings? Ravens DC Mike Macdonald is the author of some of the league’s most wackadoo blitzes and pressure paths. He wants to move people around the line of scrimmage. Given Simpson’s turbo-boosters and the Ravens’ lack of an organic pass-rush, it wouldn’t be a surprise to see him consistently play on the edge as a blitzer in the early goings of his career. From that spot, he can attack or drop, a luxury that Macdonald doesn’t have with all of his current edge-defenders.

Early on, Simpson might be more of a ‘defensive weapon’, one shuffled around the formation and used in specific packages, rather than a developmental linebacker.

87. San Francisco 49ers: Ji’Ayir Brown, S, Penn State

88. Jacksonville Jaguars: Tank Bigsby, RB, Auburn

89. LA Rams: Koby Turner, DL, Wake Forest

90. Dallas Cowboys: DeMarvion Overshown, LB, Texas

91. Buffalo Bills: Dorian Williams, LB, Tulane

92. Kansas City Chiefs: Wanya Morris, OT, Oklahoma

93. Pittsburgh Steelers: Darnell Washington, TE, Georgia

Washington was the 11th overall play on my draft board – and the top tight end. NFL Network reported mid-draft that teams had a medical red flag on Washington: there are issues with both of his knees, which clearly hurt his draft stock.

That’s a big concern. But at 93, the risk is worth the reward. I’d like to remind you: Darnell Washington leads this class of tight ends in career *takes a deep breath*: Yards per target average, depth-adjusted yards per target, yards per reception, missed tackles forced per reception, yards after the catch per reception, and explosive play rate.

He is the athletic phenom of this draft class. It’s not often you see a 6-7, 270 lbs player hurdle defenders. Washington does it on the regular!

At Georgia, he was ostensibly used as a sixth offensive lineman. And he’s a mauler in the run game. But there’s plenty of untapped potential as a receiver, too. He averaged 17.2 yards per catch over the course of his college career. On those 45 receptions at Georgia, he forced 14 missed tackles and averaged 7.5 yards after the catch per reception. Georgia didn’t need him to be a down-the-field dynamo. In the NFL, that potential could lead to something truly special.

Washington will never be a flex-him-around-the-formation guy. He doesn’t have the subtlety or instincts of Dalton Kincaid as a route runner. Developing that stuff is tough. But, right now, he is the perfect combination of clean-fit-with-high-upside within the Shanahan-LaFleur-McVay-style wide-zone-then-boot offense. In the run game, he can hold the point or put a dent in the defensive front. He has the burst to press downfield in the passing game, and enough wiggle to create separation one-on-one.

It comes down to this, for me: the Shanahan-style offense is built to put a two-way stretch on the defense and pierce a hole at the second level, with receivers catching the ball on the move in the void between a (pushed back) secondary and (drawn up) front. That doesn’t require a tight end to detach from the formation (though it’s a nice addition), but it does require them to be a net positive in the run game. I ask you this, who would you be most worried about grabbing the ball at the second-level with a runway? If you answer Sam LaPorta, I hear you. For me, that guy is Washington.

For the Steelers, it’s a dream fit. They want to hammer people with the run before taking some shots on turn-the-back play-action. When they jump into some of their spread work, when Kenny Pickett engages point guard mode, they can take Washington off the field if needed. But there’s also a world in which he develops as a route runner and is more comfortable detached from the formation – if not as a body presence over the middle of the field, at least as a red zone target.

You never know with medical red flags. Washington is an athletic marvel. And when you get an athletic marvel with bad knees it’s fair to wonder what kind of athlete you’ll be left with if the knees go. The Steelers could be left with an auxiliary offensive lineman, the kind of player you can find in undrafted free agency. But in the third-round, that’s a gamble worth taking. The Steelers could end up with the top tight end in the class and the steal of the draft if Washington can stay healthy.

94. Arizona Cardinals: Michael Wilson, WR, Stanford

Speaking of staying healthy, how about this for a flyer from the Cardinals?

It’s pretty clear the new Cardinals, umm, brain trust had little interest in overhauling their roster in this draft class. Instead, they decided to roll things over to the next season, gathering as many assets to attack the 2024 draft as possible.

That makes some sense. What first-time GM and head coach wouldn’t like to spend a year getting their feet under the desk, figuring out how to run an organization and want they want to build over the medium turn, ironing out all of those rookie year issues, before entering an offseason with a bunch of fire-power in the draft?

Kyler Murray’s injury probably pushed Monti Ossenfort and Jonathan Gannon, into embracing year one as a Year Zero, rollover season.

With the players they did select early in the draft, they took some high-upside swings. Wilson was one. When healthy, he was dominant at Stanford across multiple seasons, playing in an honest-to-goodness pro-style offense with a fully developed route tree. He is a three-level threat who lined up in every conceivable spot across the formation. Wilson has good deep speed and outstanding body control once he takes flight; he plays bigger than his frame and is happy to make catches on collision.

But Wilson struggled to stay on the field. He suffered a number of season-ending injuries and missed a lot of time in three different seasons. When on the field, he showed all the tools to be the ideal second receiver in any offense. But there might not be a sports book around that would take the wager that he will stay on the field.

95. Cincinnati Bengals: Jordan Battle, S, Alabama

Jordan Battle stands as this class’s safe pair of hands. There probably isn’t a cleaner fit in the draft than him stepping into the shoes vacated by Vonn Bell in Cincinnati.

Battle played for four years at Alabama, learning the nuances of football’s most exacting systems. He has a solid frame (6-1, 206lbs) and has experience executing every single alignment and assignment that is asked of modern-day safeties.

Battle likes to play with the game in front of him. He isn’t a fluid enough athlete to twist this way then that, either scampering across the field to make a play or turning and running to break up a deep shot over his head. He prefers to sit in a zone and rely on his instincts to fire downfield. He’s smart, stays within himself, and executes all of the little things that add up to wins.

Some of Battle’s measurables are concerning. He isn’t an explosive player. He doesn’t have the twitch or lateral quicks to be a truly positionless safety, the kind all teams are scanning for. He finished 32nd among safeties in RAS, per MathBomb. That’s concerning. But Battle outperformed his pre-testing expectations. Given his lack of range on tape, finishing with greens across the board in the ‘range’ category is a plus. Battle isn’t a dunker, but he plays with unteachable, two-step-ahead vision.

As we continue in this era of coverage variability, teams want safeties who can do bits of everything, rather than a one-dimensional ‘free’ safety and a classic ‘strong’ safety, a safety who rolls towards the line of scrimmage or stands in the box. At a minimum, both safeties need to be comfortable covering hashmark to sideline, and quick-fitting versus the run. Nobody toggles his coverage schemes snap-to-snap or week-to-week like the great Loudini.

The NFL moving to an increase two-deep structures means that — depending on the pre-snap motion or shift of the offense — it’s hard to have a single player designated as the deep safety and one as the rotator fitting up in the box.

That’s where Battle has value. He can bounce around the formation, slotting into what assignment the coverage demands or the matchup dictates. He will never be a leave-him-on-an-island safety who can sit on his own on the back end of the defense. But he’s athletic enough to play in two-deep structures, and he’s such an instinctive defender underneath that he can bring real value as the lesser part of a tandem.

Plus, he has enough size and pop in his pads to play as a dime linebacker in obvious passing situations, leaving the speedsters to cover all the deep stuff on the back end.

Battle might never be a game-breaker, but he’s the kind of player a coach will be happy to have on the field on third-and-seven in December. In this class, that’s going a long way. Over the span of the second and third rounds, Cincy was able to get more flexible and explosive in the defensive backfield. Lou Anarumo will be happy.

96. Detroit Lions: Broderic Martin, DL, Western Kentucky

Confession: I have yet to study Broderic Martin. But I can tell you this: his tape vs. Auburn is whispered about like it’s some kind of hand-shake-only club in East Berlin. If you know, you know. I am eager to report back. I have my whistle and glow sticks ready.

97. Washington Commanders: Ricky Stromberg, IOL, Arkansas

It’s rare, unless you’re a super dork, to be excited about a third-round center. But I’m telling you: get excited about this one. Stromberg to the Commanders is an ideal fit.

Back in the early portion of the offseason, I sat down with the chief voice of Washington X’s & O’s analysis, Mark Bullock, to discuss Eric Bieniemy’s offense and how it matches up with the Commander's core. One thing that was clear: To run the kind of offense that Bieniemy prefers, a power-spread, where any five of the offensive lineman can pull and move into space, the team needed to get more athletic at center.

Drafting Steve Avila and moving him to center was my pick back then – and I have a sense that the Commanders would have loved to have done just that if the board had fallen their way – but this is a good backup plan.

Stromberg is an outstanding athlete for the position. Kendall Briles weaponized Stromberg’s athleticism in his go-go, smashmouth-spread offense. Stromberg is an effortless mover in space. He doesn’t have a great feel – yet – as a move blocker. He’s guilty of over-extending and reaching before he’s hit his landmark, losing some of his punching power or allowing defenders to slip blocks. But he’s able to cover ground that few others can; the technique is coachable; his ability to hit those landmarks in record time is not.

There’s development needed in pass protection, too. Stromberg doesn’t bring much pop inside, despite his solid base and size. He has conceded zero sacks over the past two years, but there’s plenty of noise in that state: he has been beaten cleanly by strong power-rushers who were unable to close or who forced the quarterback to bail out of the pocket.

Stromberg isn’t the finished article today. But he fits everything that Bieniemy is looking for in a center: A smart, athletic player who has the feet to pull to the perimeter.

98. Cleveland Browns, DL, Siaki Ika

Siaki Ika was the top pure-nose tackle in this class. He’s a vintage drop-his-ass-in0-the-A-gap, dare-you-to-move-him-off-his-spot, kind of lineman. That’s a pro and a con: He has a clearly defined game and he’s already mastered it. But there are questions about his ability to rush the passer in obvious pass-rushing situations, and what value he can bring to a team if he cannot shoot upfield. Mazi Smith, another top nose tackle who the Cowboys took in the first-round, can point to his athletic profile as proof that there is more to come as a pass-rusher, and can point to his scheme (and the technique he was asked to play) at Michigan as to why he wasn’t able to showcase that side of his game more pre-draft.

Ika defenders (and I count myself among them) will point to the development of Vita Vea, who became a valuable pass-rusher at a heavier size once he was in the league. Detractors will point to a slew of one-dimensional, one-down, one-tech tackles who cannot get on the field for more than a handful of snaps a game. Ika was one of the worst pre-draft testers in this class. He finished 1176 out of 1620 among DTs tested between 1987 and 2023 in Relative Athletic Score.

Not great. But that’s not Ika’s game; it wasn’t in college; it was never going to be in the pros. He’s a hulking presence inside who jars interior linemen, latches on and then sheds to the ball-carrier. The Browns needed more girth along the interior, and that’s what Ika will provide. He might never develop into anything more than a run-clogging, sumo wrestler. But if that helps unlock the team’s speed-skaters on the perimeter and allows the second-level to player quicker vs. the run (a huge issue for a historically atrocious run defense last season), then Ika will have been a worthy third-round pick.

99. San Francisco 49ers: Jake Moody, K, Michigan

100. Las Vegas Raiders: Tre Tucker, WR, Cincinnati

101. San Francisco 49ers: Cameron Latu, TE, Alabama

102. Minnesota Vikings: Mekhi Beckton, CB, USC

I remain utterly baffled by the Vikings’ plan for their secondary. A reminder: They hired Brian Flores this offseason to reconstruct an aging, flagging defense. Flores runs press coverage at the highest rate of any defensive coach in the league. He’s never met a down or distance that he doesn’t want to blitz. His scheme puts a ton of pressure on his corners to all live on individual islands and to plaster onto receivers all over the field. He plays some zone, but not a lot. There’s little press-or-trailing. It’s old-fashioned, bump-and-run coverage. In coaching parlance: MEG coverage. Or, man everywhere he goes. There’s no wink or nods or falling off. (there are some cone concepts, morphing double teams, but only against elite wide-outs)

And so, with this staunchly doctrinaire coach, the Vikings have provided… this:

Andrew Booth Jr.

Joejuan Williams

Byron Murphy

Akayleb Evans

Tay Gowan

Woof. If you squint hard enough, you can find some talent there, but it’s a crop of players ill-fitting to Brian Flores’ scheme. All, besides Williams, have played their best football on zone-dense defenses or in press-and-trail schemes. They’re not bump-and-run, follow-the-man-everywhere-he-goes type of corners.

How did they address it? First, they passed on Deonte Banks. Then, they had a long, long wait until their second pick, the final pick in the third-round. With that pick, they took Beckton, a sixth-year senior out of USC with okay-ish athletic traits but without the experience or skills to live in an all-press, all-the-team sort of system.

Beckton is a see-then-attack corner. He has experience playing inside and outside. But he’s been at his best when he’s able to play on the half-turn, using the sideline as a help defender, sinking to depth, and then driving down and attacking the ball (or receiver). He is spiky at the catch-point. He’s aggressive, and makes plenty of plays on the ball.

He also just so happens to be rail thin. He’s a net negative versus the run. And his technique when up in press is lacking. He’s more of a shadow fighter, trusting his feet more than his hands. He doesn’t want to get up and fight the receiver; he wants to wait and attack the ball in flight.

That’s fine! It’s great! It fits and works in certain schemes. In a Flores scheme? Hmmm.

Unless Flores has undergone a personality transplant that we’ve yet to be made aware of, the Vikings’ entire offseason strategy to re-shaping their defense has been questionable.