Plays the NFL should pinch from College Football: Part III

Has Oregon State shown the future? Plus, an Urban special and amplifying the screen game

We’re continuing with our series on the plays/concepts/designs that NFL teams should look to pinch from college football.

Football is a bottom-up structure. The inverted pyramid of pressure allows guys at the high school level to innovate, college guys to evolve, then the pro guys to steal, often laying claim to creation in grand, sweeping media profiles of their genius. That’s the game.

NFL coaching staffs comb through film wherever they can find it (the SEC, PAC-12, high school, Japan) to find creative designs that can help on Sundays — the Chiefs under Andy Reid, for instance, dedicate one member of staff to trawl through high school, international tape, and social media to find the whackiest and most imaginative designs.

One of the joys of the pre-draft process for those of us no longer writing about college football on the daily is being able to dive deep into the schemes, systems, and individual designs that are new or interesting at the college level. Over the coming weeks, we’re going to dig into some of the most compelling designs from college football that pro teams can pinch and install for the upcoming season.

If you missed Part I on Lincoln Riley, you can find it here. If you missed Part II on the return of the Chip Wagon, you can find that here. Now, fair warning. Things are about to get weird. It’s time to pop in a gummy and head to college football’s outer-most dimension.

Oregon State Two QBs

If you find yourself in a conversation about the most underappreciated coaches in the college game, it won’t take long before Brian Lindgren’s name comes up.

You want to see the most fearless offense in college football? Cue up Oregon State and watch, jaw agape, as Lindgren’s group blends classic wide-zone and west coast principles with some two-quarterback madness.

Yep, you read that right: TWO quarterbacks.

Okay, not precisely two quarterbacks. More of a one ‘true’ quarterback plus a hybrid player — one capable of aligning anywhere in the formation, including as a quarterback.

It’s the blend that makes the Oregon State offense so fun to study: They’re effective at full throttle in their wonkiest sets and at slower speeds, grounding fools to submission with vintage kick-and-go wide-zone variants.

The base of Lindgren’s offense has a similar look and feel to the final days of the Kyle Shanahan-Mike McDaniel partnership, using motions and shifts to create numerical overloads in the run game. We know all about that stuff. But what about the whackier devices?

Finding ways to maximize two QBs — or, at least, two ‘throwing’ threats — is one of the next frontiers of offensive development. Teams across the football landscape have studied the KG Fighters of the Kansai Collegiate American Football League, the most wackadoo offense in all of football, in hopes of stirring some inspiration.

At the NFL level, we’ve seen teams dabble with two-quarterback gimmicks before. The Ravens gave it a go with the fumes of RGIII and Lamar Jackson. But it was a style trading on its trickery, hoping that the defense would get lost in the confusion and get caught in the wrong personnel grouping or find themselves misaligned at the snap.

That’s cute. It’s fun in spurts, though often ineffective. Lindgren’s style is something more profound. Last season, Oregon State didn’t design a batch of trick plays with two quarterbacks on the field. Nor was in an appetizer for some sort of double pass, or handing the ball to a capable wide receiver every once in a while to catch a defense sleeping.

Instead, Lindgren used a quarterback convert as a do-everything offensive weapon, opening up all sorts of possibilities within the base of the offense. Rather than sticking an extra quarterback on the field to create confusion, Lindgren had a legitimate hybrid tight end/fullback who could step into the spot as the quarterback on any given play.

Behold: The Jackhammer.

That’s Jack Colletto, a 6-3, 240 lbs Swiss Army Knife. The Jackhammer lined up anywhere and everywhere in the formation. Fullback, tailback, attached to the formation as a tight end, detached from the formation as a tight end, split outside the numbers as a bleeping receiver, and as a quarterback, in the gun or under center. He was a bruising runner and blocker, but one who spent the bulk of his career learning as a quarterback, making him just good enough to be a real threat as a thrower — and savvy enough when asked to split out and run routes.

As a runner, he was tough to stop. Of the 24 running plays he took at quarterback, Colletto converted 22 into either a first down or a touchdown. But he also took carries — and churned out yards — running the ball as the up-back in two-back formations and as a stand-alone running back in single-back sets.

It’s rare to see a team live (or almost live) in a system that features two genuine rushing and throwing threats at quarterback. Oregon’s state starters (Chance Nolan and then Ben Gulbranson) were mobile enough players to make spread-option principles a foundation of the offense — and beefy enough to hold the point in spurts. That meant that when toggling into alignments that put the Jackhammer at quarterback, Lindgren wasn’t changing the offense wholesale, tipping the hand to the defense. No, he was just running the regular offense with a beefier option at quarterback — someone who could slam into the line of scrimmage and who was good enough to throw down the field to give the defense fits.

Again, that can sound gimmicky. But it’s not. Because the Jackhammer's main role on the majority of snaps was to be a battering ram in the run game, be it as a fullback out of the backfield or as a tight end up on the line of scrimmage.

Unlike the RGIII-Lamar comparison, where teams got a tip that something funky was based on who was in the huddle, teams facing Oregon State had no idea when Colletto was on the field whether they’d be facing a basic wide-zone concept, whether Colleto would sprint out to catch a pass, or whether he’d slide into the quarterback role and dive head-first into the line of scrimmage.

It was effective. How do you prepare for a system where any of the following are possible from the same damn personnel grouping: the offense jumps into a five-wide set with Colletto lined up as a wide receiver; a 3x1 set with Colletto up on the LOS as an in-line tight end; a 3x1 set with Colletto flexed out as a receiver; a single back set with Colletto in the backfield as a running back; an I-formation with Colletto lined up as a fullback; a 2x2 set with Colletto as the quarterback. Oh, and if you guess right and set the right numbers to the right areas (inside the box and coverage on the back end), you’re facing an offense that is liable to motion or shift into a different look before the snap.

The key was not Colletto being a dummy weapon, as is often the case in these spookier designs, but that he was a real threat as an in-line blocker as a fullback or tight end. You not only had to prepare for it; the expectation was that he’d be leading the charge out of the backfield as a blocker. And then — BAM!

That’s real juice for a quarterback convert. Colletto played quarterback at a lower level before adding bulk to his frame and switching positions at Oregon State. Last season, he took snaps as a linebacker on defense and ran down on kickoffs on special teams as well as being the team's short-yardage go-to as an auxiliary quarterback and fullback/running back.

The two-quarterback stuff scared the bejesus out of everyone. The options were endless — and defenses were punished.

The base of the offense matters here — and that’s what will intrigue NFL sides. Lindgren’s offense is, in essence, a modern pro-style system. It’s Shanahan ball, sprinkling on some of the RPO and option goodness that’s a requirement at the college level. But needing to prepare for the wide-zone looks with a fullback in the backfield is what makes shifting that picture at that last second so goddamn difficult to stop. It’s less a ‘two quarterback’ offense than a two-offenses-in-one. Try to slow one, and the offense can shift to the other at the line of scrimmage. Gulp.

Using a sledgehammer as a wildcat quarterback in short-yardage situations is nothing new. But what is a fresh wrinkle is this: Needing to defend every blade of grass on every single play against a personnel grouping with two throwing threats. Usually, a wildcat setup constricts the offense. They can no longer run base plays. They’re trying to expose a gap in the front to then hit it as quickly as possible for a short-yardage conversion. And that’s true with Lindgren’s group, too. But Colletto serving as both a thumper in the run-game and as a former full-time QB (and the starting QB being a plus-athlete as a runner) allowed the Beavers to keep every option available to them in their book regardless of who wound up taking the snap.

There is some trickery. But really it’s just good ‘ol fashioned confuse-and-clobber offense. Few offenses made defenses chase ghosts like Lindgren’s group in 2022. No matter the personnel grouping, no matter the formation, no matter which player wound up catching the snap, they could bludgeon foes with the run or his explosives down the field:

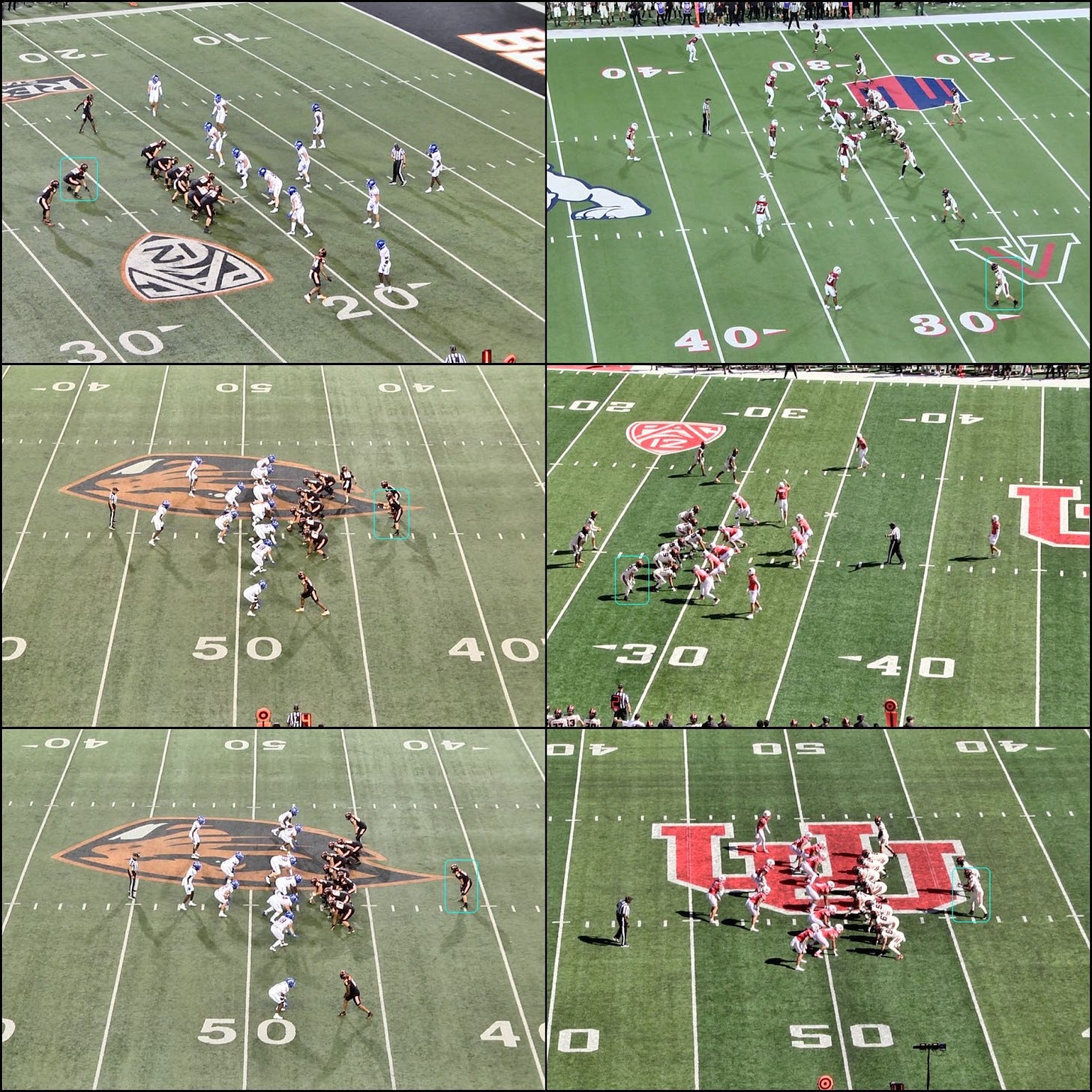

Now we’re talking. Oregon State exits the huddle in a tight, condensed formation with their two ‘quarterback’ threats in the backfield — only this time the Jackhammer is lined up in the gun as the quarterback with the starting QB, Chance Nolan, riding in the sidecar as a running back. The defense knows something is up. IT’S JACKHAMMER TIME. You can see the communication seeping through the screen. They’re running their bullshit stuff. The big fella is going to go crashing into the line of scrimmage. Pinch all the interior gaps. Build a wall.

And then, chaos:

Nolan bolts up to the line of scrimmage. The Jackhammer walks back into the single-back, running back slot The defense has seen this drill before. Sneak! Sneak! Sneak! We’re on third and short. A late movement from the quarterback tips the hand. They tried to mess us up with their formational weirdness, but it’s just a basic sneak! HAHA! Wait? We’ve closed all the inside gaps. What if it’s a hand-off to Colletto?

The linebackers and safeties pinch down to three yards off the ball to help fit up against Colletto.

Boom.

Wrong. It’s a play-action shot — a post-over; the most basic of play-action shots. The defense is left scampering. Thanks to the pre-snap alignment and movement, the defense has left itself in cover-0 against eight-man protection with Oregon State’s leading quarterback sat back in the pocket — a cavernous pocket, at that. Both receivers are wide-ass open. Oops.

Do you know how tough it is as a wide-zone-then-boot-oriented offense to get two guys open on a simple two-man concept with the cleanest of clean pockets? Usually, you’re trading out one for the other. The Beavers scored both on the same play.

Why? The Jackhammer, of course! Remember: this wasn’t a magic trick. Lindgren did not devise a one-off, quirky, concept. Draw up the final play and you have the most basic play-action shot in the arsenal: a single back set with a post and an over route. It’s precisely because it’s not unorthodox for Oregon State that it works. Colletto gathering the ball as the quarterback or after he shuffled into the running back spot were both legitimate options to be concerned about because he’s a legitimate threat at both.

It’s not gadgetry. It’s just the offense.

*Takes the bong from Sean Payton*

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Read Optional to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.