Quads, Quads, Quads, Quads, Quads, Quads — Everybody!

As defenses have shifted en masse to two-deep coverage shells, offenses have countered by building in an increasing number of 4x1 formations

The NFL is in the midst of a mini ‘Quads’ boom.

A quads formation is as it sounds: Four eligible receivers to one side of the field. At the NFL level, four receivers to one side typically means an offense lining up in what looks like any number of trips (or three receiver) sets with a running back set to the same side as the eligible receivers, lined up in the backfield.

Ever since Patrick Mahomes graduated from interesting prospect to destroyer of all worlds, Andy Reid and the Chiefs have delighted in soning fools with a bevy of such four-strong concepts – ‘Spoke’ being perhaps the most infamous – that floods zones, releasing the back late out of the backfield to create a clear overload to one side of the formation.

Running with a true four-receiver, empty set out of the huddle has been a more limited package in the pros. At the high school and college levels, true quads formations are more prominent. The width of the hashmarks at the lower levels allows a coach to stick four receivers to one side of the field and not have to worry about silly things like spacing. Running such looks with the NFL’s narrow hashes is tough. Things are more cramped to one side of the field; lining four receivers up with even spacing can get all sorts of congested, making it tougher to run a sound route concept and tightening throwing windows.

And then there’s the other issue: If there are four receivers to one side of the field, the offense is signaling its intent. They’re not just splitting the field in half, they’re holding up a sign, taking out a billboard, and sending a man out in the street with a bullhorn and siren and doomsday prophecies. WE’RE RUNNING A PLAY TO THAT SIDE OF THE FIELD.

Such predictability has, typically, been antithetical to the very essence of pro coaches. At the lower levels, running such half-field reads serve as a tidy way to hide a quarterback who struggles bouncing through progressions from one side of the field to the other. It can more clearly define reads. But when you have Aaron Rodgers or Tom Brady or Matthew Stafford, who cares?

The most common ‘empty’ formation (no one in the backfield) in the NFL is a more balanced 3x2 formation:

Doesn’t that just look right? There’s a nice, even amount of spacing between receivers. The two sides can intersect, or a coach can design a two-man combination to one side and a three-receiver combo to the other side.

In 3x2 shots, coaches can build in all sorts of formational diversity. Maybe there’s a bunch to one side and even spacing to the other. Maybe it’s a double-stack situation. Maybe there’s a pair of wings, ready and willing to chip as they release out of the backfield, adding extra beats to the passing progression while still having a receiver release on either side of the field at the snap — an issue with a 4x1 look.

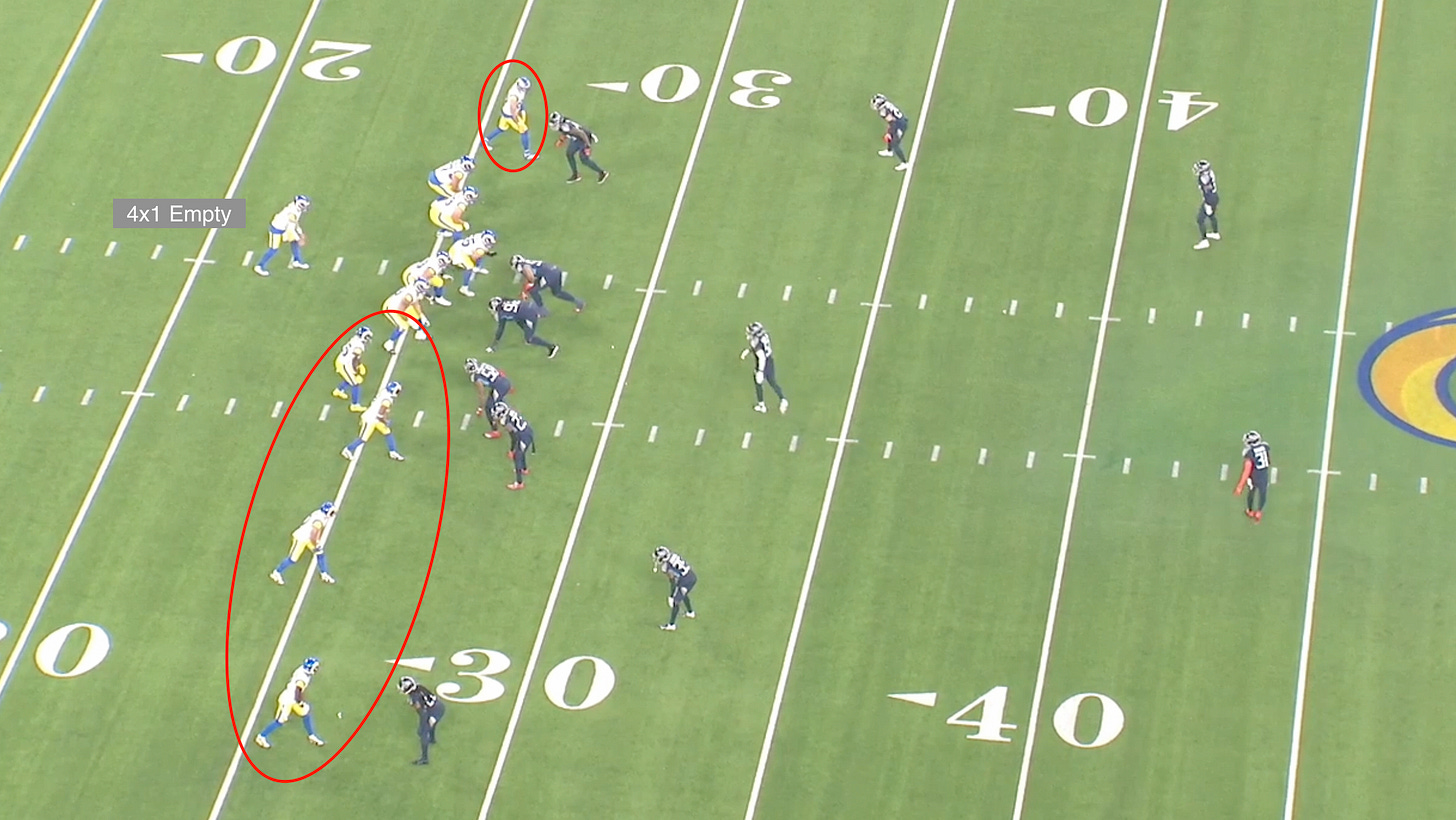

But while 3x2 sets remain standard practice, the use of 4x1 sets is on the rise. As defenses have shifted en masse to two-deep safety structures to try to limit the wide-zone-then-boot offenses that have drifted throughout the league – and to target some of the more traditional Air-Raid concepts coming out of Kansas City and Arizona – coaches have had to find solutions. The influence has filtered throughout the league. Even the tanktastic Lions are beaming 4x1 quads looks into the homes of unsuspecting turkey guzzlers on Thanksgiving Day:

Be still my heart.

Like all modern offensive concepts, the goal is to dress the defense vertically and horizontally from the same structure. The two-deep safety shells that are en vogue around the league allow defensive coaches to do two things: To toggle between two-deep and four-deep coverages within the same concept; to build extra layers into their defense than traditional single-high or cover-3 designs. Planting four receivers on one side of the field allows offensive coaches to still get to their preferred offensive concepts and overload zones even with extra defenders allocated to that half of the field.

Defenses at the NFL level are able to manipulate coverage with more authority than at the college level (save for Alabama, Georgia, and some of the more sophisticated teams). What looks like quarters or cover-2 can rotate into cover-6 or six-cross or any number of inverted or trap looks in a flash – and indeed that has been the focus of the league’s top defensive minds for the past 18 months.

Still: With so many receivers allocated to one side of the field, there are only so many options within a defensive coordinator’s playbook if they want to match numbers to each side of the field. A four-man look typically forces the defense to check into a more basic coverage; they will match up in man-coverage, allowing the offense to attack with one of its basic man-beater principles; or they’ll sag off into spot-dropping zones, hitting landmarks rather than bumping a receiver and then hitting there zone and then converting into man-coverage, a more advanced style that the league’s top units embrace. Whichever option the defense toggles too, that represents a win for an offense if it’s trying to make life easier for its quarterback and a receiver that demands a whole host of defensive attention – say, Davante Adams or Cooper Kupp.

It’s tough for a defense to run a more complex cone coverage or a moving double team if a top receiver is somewhere on the four-receiver side. And if that receiver is isolated as the ‘one’ on the backside of 4x1, well, then you have a tricky decision to make: To double that side and give everyone else a clearly defined one-on-one on the other side of the field; or to take your chances with Adams, Kupp or whoever is playing one-on-one, with no safety help behind and room for them to move into, given that, you know, all four other eligible players are running into space on the opposite side of the field.

Through film study, it isn’t tough for an offensive staff to get a read on the specific check defensive coaches are making vs. quads formations. And once you can say with some level of certainty ‘hey, they just check into man-free’, then it’s easier to design specific concepts to attack that check.

Gulp.

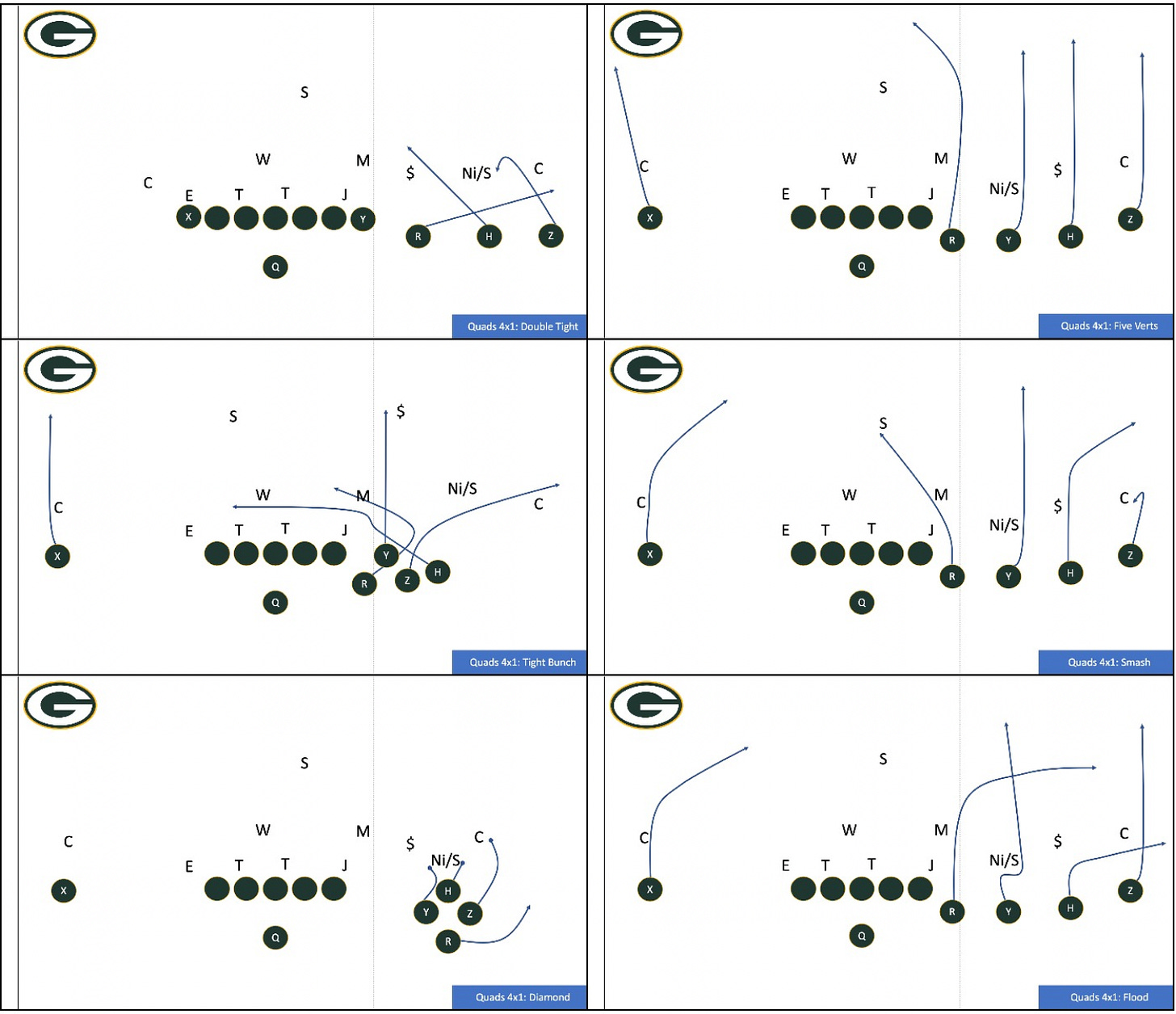

No one has invested more in 4x1 sets than Matt LaFleur and the Packers. Ever since he rocked up in Green Bay, LaFleur has set to work adding as many 4x1 designs as possible. Each and every week you click through a Packers game, there they are, just hanging out, no fan-fare. And (almost) every single week, there are the Packers, picking up one of their precious explosives, running an offensive set that, at root, is more commonly seen on Friday nights than on Sundays.

Entering the season, a batch of coaches were faced with the same issue. Their base structure was the same – outside-zone and then boot-action shots down the field. They torched single-high safety coverages. Defenses evolved: playing more two-deep safety shells; playing the pass (and the quarterback) on wide-zone looks rather than honoring the run.

Let’s take Sean McVay, Kyle Shanahan, and LaFleur for now. All three were champions of reinvigorating the out-then-boot style. All three found success — lots of it. All three have bumped up against the same issues. Each has sought a different solution this season.

Sean McVay has leaned all the way into super spread sets. The fun-and-games and motions and shifts that used to be a core component of his offense have vanished. Now it’s spread, empty formations, with isolation routes. All the pressure has been shifted to Matthew Stafford’s eyes, arms, and feet. Take us to the promised land, QB.

Kyle Shanahan went with the Draft-Trey-Lance strategy. The idea: To put a power-runner and thrower into the out-then-boot offense, a combination the league has not seen during the latest boot-action surge. Pair those typical Shanahan-ian run structures with some Ravens-style power-read goodness and you have yourself a frightening cocktail – at least in theory. The results are still TBD.

Matt LaFleur hit on a more organic strategy. Hey guys, I have Aaron bleeping Rodgers! LaFleur tweaked his offense, keeping the bulk of the base and shifting some of the specific designs, banking on more formations and increasing diversity to keep the machine rolling.

In the run-game, there are more gap-scheme designs (linemen pull and moving) that work in tandem with the Packers’ motion package. Now, motion is not just about shifting the eyes of the linebackers. Now, like Shanahan and the Niners escort motion, the idea of moving someone pre-snap is about gaining a leverage advantage and adding a late-gap somewhere to proceedings. The Packers counter package is particularly frisky. You line-up against a typical outside-zone look, and all of a sudden there’s a tight end motion, a receiver motion, and the tight end converting pulling across the formation from the wing:

Spicy.

But where LaFleur has really looked to expand this season is in the increasing number of unmirrored looks to try to swamp two-deep coverages. LaFleur’s four-man designs are becoming the stuff of legend — people gather and whisper in dank pubs; secret handshakes have been introduced for those in the know.

LaFleur’s preferred style: The fast motion. It’s as simple as it sounds. The Packers lineup with three eligible to one side of the motion. At the snap, they motion someone – a back into the flat; a receiver from one side to the other – to the three-receiver side to create a four-man wall.

The motion not only gives the quarterback a better shot at ID’ing the coverage, but it gives the defense less time to react to a quads set. Defenses will default to standard, static looks. And if there’s one person in the professional game that you do not want to be standard and static against, it’s Aaron Rodgers.

The bulk of fast-motion designs are built with a running back in the backfield, set to the trips side of the formation. In that way, it functions more like Andy Reid’s preferred packages in KC. There are still four allocated receivers, but it’s not a true quads set in the strictest definition of the word.

It’s on the hardcore stuff where LaFleur is at his best, though. And that has little (though obviously some) to do with Aaron Rodgers. It’s about Davante Adams.

LaFleur is a master at leveraging the threat of Adams – the league’s best receiver – into making life easier for everyone around. Yet rather than do the boring old thing, relying on Adams to draw a double team, isolating him to one side, and hoping everyone else can feast, LaFleur finds a way to *shock horror* still get Adams involved in the action even if defenses are committing resources to stop him.

Enter: Quads. As noted earlier, it could be an isolation look, with Adams on the backside. With four instead of three receivers to the other side, it’s difficult for a defense to slide a second defender over to help cover Adams.

Look at that. The Chiefs are forced to commit everyone to the four-receiver side. Adams is left one-on-one on the backside. The Chiefs’ deep safety is conflicted: Does he keep tabs on Adams and try to scurry down to take away the receivers’ inside path? Or does he shuffle to hit right, because it looks an awful look like the Packers have a free player screaming up a seam?

There are no good answers. The only answer, it seemed, was to penalize Adams, limit the damage, and live to play another down.

Where LaFleur and Rodgers really find their groove is when they kind of, sort of conceal Adams within the play design:

That is downright mean. It’s a bastardized version of a Smash-Divide/Dagger concept. And it’s a filthy beater vs. cover-2.

The corner route occupies one deep safety; the boundary corner must squat on the back flaring from the wing position to the flat, who chips and then releases to buy his quarterback more time — and to better set up the timing of the concept. He’s the outlet ball. There’s also a shot play right down the pole unless the middle linebacker turns to match that route or the backside safety can corral across.

Hanging out there, right on the edge of the action, is Davante Adams. He starts outside, working inside. It’s his favorite route, the Dig. As ever, he’s looking not at the defenders, but eyeing the space. He wants to sit over the top of the deepest linebacker and arrive over the top of the ball in front of the safeties.

Again, there are no good answers. Because even the good answers – from that coverage principle – lead to a bad result. The two safeties pick up the post and the corner. And so there comes Adams working unto the middle of the field with all sorts of grass ahead of him. Rodgers reads and flips the ball to Adams for another, easy, explosive play. If there’s something more there down-the-field, great. If not, Rodgers can work back to an easy completion to, who? Davante in the middle of the field. I mean, come on, people!

Give LaFleur the Coach of the Year award just for what he did to the Cincy defense in week five, I say.

As the season has progressed, LaFleur has continued to work in four-man combinations to try to generate explosive plays against two-deep safety coverages. Defenses have struggled to find the right solution – the Packers are currently tenth in the NFL in explosive pass rate; not great by Rodgers sky-high standards but not awful given the coverage shells they’ve and having to chuck Jordan Love out there for a game.

Run through that a time or two. Look at the pre-snap picture: The Vikings are in a two-deep safety set, with Harrison Smith, the team’s best player, lined up over the top of the Packers’ isolated receiver on the backside of a 4x1 set. The Packers are in quads. Davante Adams is the second receiver in from the sideline, nicely slotted between a boundary receiver and a pair of inside receivers, one in the wing spot (off the hip of the left tackle) and the other in the typical slot spot.

What are the Vikings to do? Do they leave the backside receiver one-one-one to try to double Adams? Do they leave everyone on the four-receiver side one-on-one? They’re in a bind.

The Vikings opted to keep both safeties deep, hoping that Smith could bracket any kind of deep over route or late in-breaking route from the top down. It was a decent enough idea, but it didn’t matter. The Packers ran a double corner concept.

The Packers set of a pair of chip blocks from the backside receiver and the wing. The outside receiver runs a quick in-breaking route, serving as the hot solution if the Vikings bring pressure. Adams breaks to the corner. The DB trailing him follows. Marquez Valdes-Scantling follows behind with a post-corner route, first driving to the middle of the field before flipping back to the corner.

Through formation alone, the backside corner and Smith are washed out of the play. It’s Valdes-Scantling and Adams vs. two DBs, a matchup the Packers would delight in attacking any day. Vikings safety Xavier Woods out-leverage himself, playing the post, trying to take away the middle of the field, before Valdes-Scantling breaks off back to the post for the pitch and catch completion deep down the field.

Coaches throughout the league continue to iterate. Quads formations in the pros have taken on a different shape than those in college, mostly due to the width of the hashes. Rather than stick as many receivers on the field as possible, savvy coaches are getting into bigger personnel groupings – two tight ends, a back; two backs, a tight end – forcing the defense into base personnel and then shifting into quads. That’s a standard operating procedure, but where that once meant jumping into 3x2 empty sets, now coaches are keen to hit four-man groupings to one side of the field.

Peyton Manning was a fan of the 4x1 diamond formation during his time in Denver, when he started to work in more Air-Raid concepts. By stacking four receivers in a diamond shape, he was able to get all the aforementioned benefits of four-receivers-to-one-side combinations while also being able to grant three free releases to his receivers – the two outside guys and the one at the base of the diamond – all while sticking to the condensed-to-expand principle that governed the Manning-aissance.

Kellen Moore and the Cowboys have worked in some interesting four-man looks this season. Back in his days as the Boise State quarterback, 4x1 formations were the it thing. Moore’s use of extra lineman Connor McGovern has helped the Cowboys hit on a two-offense-in-one-system that helps make the unit so difficult to defend. For 99 percent of snaps, Moore has stuck McGovern in the backfield and used him as a moveable fullback/tight end, someone who can add an extra gap somewhere along the line to help mash fools downhill.

Ah, but that one percent is really something:

There is it: 4x1. And there it is: 4x1 being run from 12 personnel, a tight end and an extra lineman on the field. The Falcons match personnel, getting big bodies on the field ready to defend against the run. Nope. Moore split a back out of the backfield and isolated him to one side. On the other side, there are two receivers, a tight end, and McGovern, the eligible lineman.

It was a rough one for Atlanta. You could almost see the Falcons defense pleading. Wait, you can do that?

Yes! The Falcons have three defenders to the one side, with only two corners over to the four-eligible side. They have three linebackers in the box, with nobody besides Dak Prescott in the backfield. It’s a pre-snap Venn diagram of oh bleep.

The Cowboys picked up easy yards – and probably should have had much more.

As defenses insist on sticking staunchly to two-deep coverage shells, playing a whole host of spot dropping zone, a see-it-then-rally style of defenses, quads will continue to become a go-to principle across the league.

There are issues. There are the same issues as ever in empty: unless you have a quarterback that can really run, there’s no rushing threat; there’s no threat of play-action, the most efficient way to move the ball; a team is limited in terms of protection. You can either slide or not. You can play big on big, or not. There’s not much else to it, though teams have been smart in using wings to chip on their way out.

If a defense sends pressure or wins one-on-one matchups upfront, and the receivers are unable to get open on what are typically slower-developing route combinations, the quarterback is in trouble.

Above, because the chips add extra beats to the play, Washington is still able to play with plus-one on the back-end, having a safety scan over the top of a three-receiver combination. Against a good front, the Packers were unable to hold up in protection.

There are pros and cons, like any formation or design; merely a tool for a coach to use.

Where quads can be elevated to the next level is with a running quarterback, or at least an offense that commits resources to the quarterback in the run game. Not only because the defense still had to mind the run even if no one is in the backfield, but because it opens the chance for even more ingenuity in the run-game. College coaches will run jets into some designs to add some running threat – and the possibility of play-action – but given that 4x1 sets remain a small part of the NFL’s setup, a defense is unlikely to bite.

A quarterback running behind a trap or power, though? Now you’re talking. If the quarterback-run is a real-deal possibility, well, then, how about adding the jet in as a. third element — perhaps as an option. How about a jet-trap from quads? We can only hope. I believe in you, Greg Roman.

This is what the next evolutionary cycle of the NFL looks like. Defenses have evolved to slow down the style that had all but taken over the league – offensive production is down across the league; the top quarterback in EPA this season wouldn’t have cracked the top five last year.

Now, offenses are finding counters to the counter, and so the wheel keeps spinning. Some have embraced a confuse-and-clobber style. Others reverting back to downhill, power runs. Others, the super spread. All have dabbled with a version of a 4x1 formation. And if not, it’s time to get started.