The Ravens defense is officially a problem

And not in a fun way

The Ravens defense has officially become a problem – and not in the fun way.

Sunday marked the third time this season that Lamar Jackson had led the Ravens to a win after his side trailed by double-digits. Against the Vikings, the Ravens trailed by fourteen points twice.

It didn’t matter, in the end, because Lamar is, well, Lamar, more an all-encompassing offense than merely a quarterback. He continues to absorb the entire creative burden of the team; and he continues to deliver. And while it’s a fun stat when discussing the impact of Jackson, it’s a damning indictment of the Ravens’ defense.

As presently constituted, there is a ceiling to Jackson and the Ravens’ success. They have the look of a Tough Playoff Out, when the realities of a fractured AFC should push them much closer to being a true contender – for whatever those distinctions mean.

The defense isn’t just bad in the conventional sense. It’s bad in all the ways you cannot be bad in the postseason.

Gulp. Part of this is the natural evolution of a team. Some parts rise, while others fall. Careful attention has been paid to surrounding Jackson with the game of talent that can help the offense evolve, though the team has steadily defaulted to the kind of boom-or-bust approach that continues to wreak havoc on that end.

Just as importantly: The Ravens are hurt. They’re not a little banged up; they’re reeling. Eleven – count them! – eleven defensive players are currently on IR, the kind of total that could sink even the most schematically sound or gifted units.

And yet even with that, there should be enough talent on the field to make a difference. They could be average-to-bad, rather than bad-to-awful. With a one-man offense – a unique player who turns every dropback pass into a form of play-action – and the all-time kicker, the Ravens should have the kind of playoff cocktail to make any opponent’s hands (or elsewhere) sweaty.

If Don Martindale can squeeze a little more juice out of the defense, the Ravens could be right there. But we’re now nine weeks through the season and Baltimore’s issues show no sign of abating. The defense has looked ragged, beset by communication issues, assignment busts, and a kind of all-or-nothing early-down approach that even blah offenses have punished.

Flip through any playbook or listen to any coach talk, from the pros down to the high school level, and you’ll get hit over the head with the same thing from page one or minute one: Win on first down.

It’s a tried and trusted coach-ism. And in the modern game, it means more than ever.

First down is the new third down. It’s where the defense gets into attack mode, particularly if the offense is liable to get into predictable looks, like, say, the Minnesota Vikings.

Getting off the field on third downs is a staple of shouty-man-on-TV analysis, but success on first downs is more predictive of long-term success. Stopping a team on third down matters, but what difference does it make if they already strung together a succession of first downs on early downs?

Winning the first down – forcing a negative play or creating a second-and-ten – is how defenses can keep up in the era of the pace-and-space, chunk play offense. While third down is when teams traditionally used to sub in their sub-packages, getting fancy with their zone-pressures or blitz looks and running unusual personnel onto the field, now first down is the go-for-it down.

Attack early. Force a loss. That’s the mantra ringing out across football at all levels. Do that, and you up your odds of cutting off a drive before it begins. The key to a good third-down defense, as coach’s like to point out, is winning on first down.

That tracks. Here is the current top-ten in Defensive Expected Points Added per play on first downs:

1. Buffalo Bills

2. New Orleans Saints

3. Las Vegas Raiders

4. Cleveland Browns

5. Dallas Cowboys

6. Green Bay Packers

7. Cincinnati Bengals

8. Miami Dolphins

9. Indianapolis Colts

10. Tampa Bay Buccaneers

Notice a trend? Seven of the top ten in early down success rate rank in the top ten in overall defensive efficiency, per Football Outsiders. Good defenses win on any down; the best defenses shut down an offense on first down.

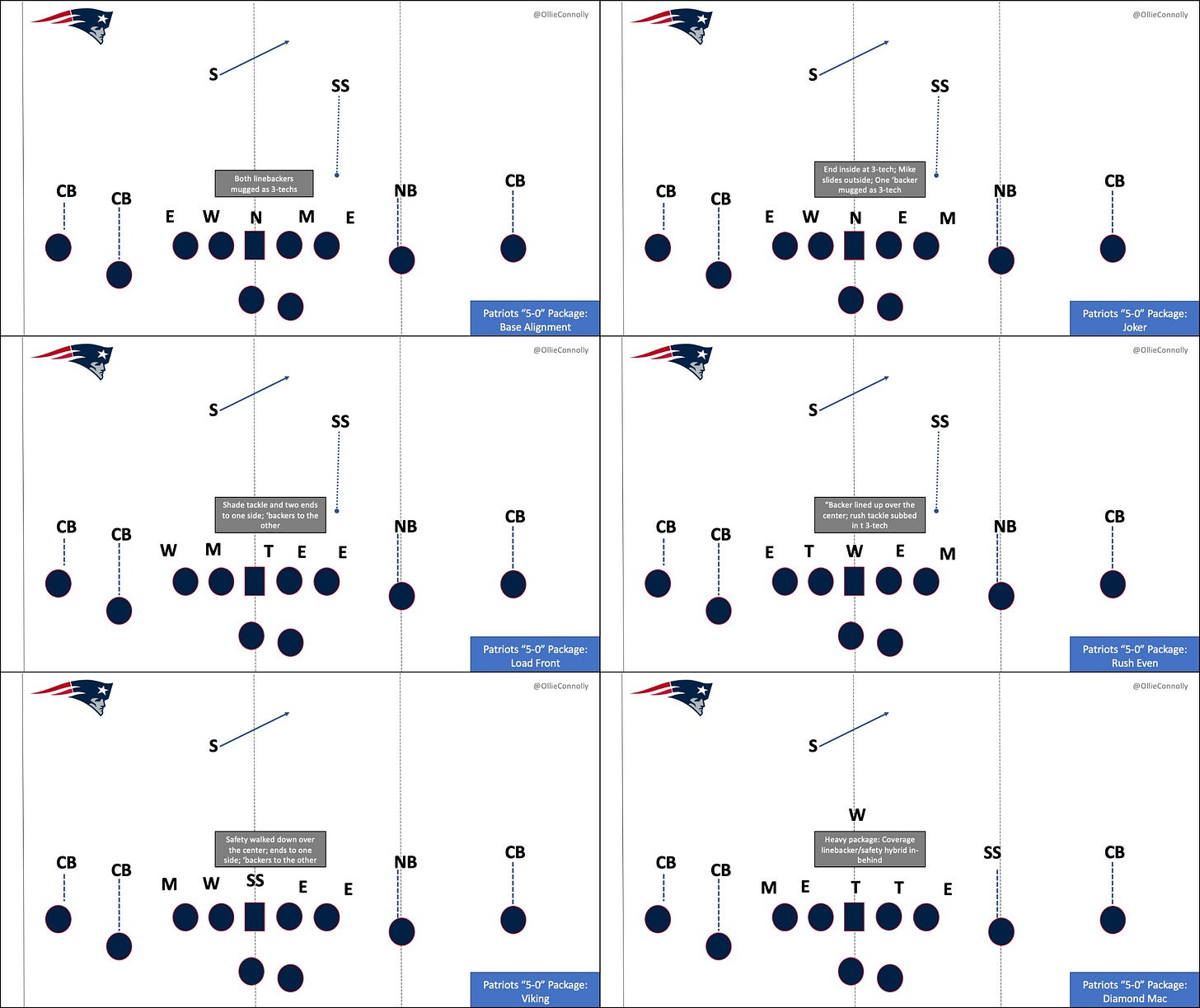

What a bunch of teams have done – like those listed above – is invert their own tendencies on first and third. Third down is now a ‘pressure’ down, with defenses using all manner of creative looks (overloads, loaded fronts, mugging the front) to draw up zone pressures. Meaning: They’re sending only four players, but those four could come from any number of spots.

Defensive coaches have copied their offensive brethren: They design pressure paths, not one-off designs. From that path – say a vintage crossdog fire-zone – they can align any player in any spot. The path remains the same, but the pre-snap presentation is different – kind of like how an offense can run the same concept from a batch of formations.

That right there is a bunch of different pre-snap snapshots that can effectively run the same design over and over again with a different presentation – string together four or five different ‘pressure paths’ and now you have 20 to 30 different play calls without much of a defensive install. How an offensive line approaches a safety walked over the center as opposed to a meaty nose tackle changes, but the same assignments can be run to the same spots.

Such zone-pressure looks make the blocking assignments hard on the offensive line, but they still only commit four guys to the rush, meaning there’s a minimal investment up front with seven defenders still dropping into coverage.

Martindale, the Ravens’ DC, is one of the best in the business at scheming up ways to get a free-rusher on the quarterback on third downs with only a four-man pressure.

On first down, that’s where the true converts will bring a good ‘ol fashioned blitz, sending five or six defenders at the quarterback and playing man-coverage in behind. It’s a boom-or-bust idea itself; commit six or seven defenders to drop the quarterback or stuff a run. If you can get the offense off-script on first down, the numbers tell you you’re winning the drive. On third down, you’re better off bringing a safe pressure.

Vance Joseph and his Cardinals defense, who rank 13th in EPA/Play on first down, send all of the heat on early downs (on all downs, really), selling out on hard on the notion that trying to pick up a TFL on first down are worth the 15-yard explosive run that may pop in-behind.

Martindale is a devout believer in both first-down blitzes and pressures. He sends everything early in the down-and-distance, hoping to disrupt the timing of the offensive drive. It might be a four-man fire-zone with an overloaded front; it might be a corner flying in off-the-edge with man-coverage behind; it might be one off-ball defender walking down to mug a gap pre-snap before dropping out while the other off-ball defender fires; or they both fire.

It’s the same logic as the Cardinals. The results: Different.

The Ravens currently rank 28th in the league in first down EPA/play, a nasty figure that sticks them in the vicinity of the Jets, Bears and Eagles. Few teams have been as ineffective on first down against the run and pass.

What should be the strength of the unit has been a consistent whiff. If nothing else, through scheme alone, the Ravens should force a ton of negative plays. They kind of, sort of do, but not nearly enough to justify the investment. Martindale’s group is currently 1st in the league in stuffed rate, but they still allow an average of four yards before a running back is touched. Every other team in the top five of stuffs concedes an average of three yards per play – over the totality of a game, that’s a giant difference.

The explosive play ranks make further grim reading. Shut your eyes Ravens fans, for your own good: Baltimore currently ranks 31st in explosive run rate and 29th in explosive pass rate on defense. That’s so bad it’s almost unfair.

Compare that with the Cardinals, again, who are running a similar all-out-attack, early-down scheme. The Cardinals are 32d in explosive run rate, conceding 34 rushes of 15-yards or more over the totality of the season. That stinks, but they’re still 12th in 1st down EPA/play, because for all the badness there’s a whole bunch of goodness. That’s the style!

Oh, and such a freewheelin’, let’s-go-get-em style has the Cardinals first in the league in explosive pass rate, conceding a throw of 20 yards or more on just six percent of the team’s defensive snaps. That’s boom or bust. They’re boomin’ or they’re bustin’. For the Ravens, it’s bust one way or bust the other.

The team’s issues against the run have been shudder-inducing:

There is a danger always in football, as in life, to assume certain attributes, certain virtues, certain values are eternal. They are not. It seems silly to expect personality from uniforms. But as fans and observers, we just do. And that is why it is with a heavy heart that I inform you that the Baltimore Ravens cannot hit anymore. There is no pop in their front. There is a lack of tenacity and ferocity to the defense. The decline in early-down vigor is jaw-dropping. Teams just walk the Ravens off-the-ball. It’s ho-hum at this point.

Few teams have struggled more this season with motion-at-the-snap. Who should be lined up where? What’s our assignment? Hey, how come we’re both in the same gap? Neato!

The Ravens defense has been consistently out-leveraged by basic designs. On the Vikings shot above, it’s a simple split-zone: the flow of the zone-run going one way, the fullback, CJ Ham, splitting back across the formation to seal the backside. The motion of the receiver at the snap kicks the Ravens second-level down a gap, with the group out-leveraging itself as Ham spliced back across the front and Dalvin Cook cut the ball to the backside.

That’s basic stuff. And that’s not the team in attack mode taking a risk. That’s the Ravens lining up, playing basic run-fit defense from their base personnel, and getting wallopped up front, with a bust on the backside to make matters worse. Teams have set principles against set formations and set motions, so that there is no need to communicate what a certain motion or strength-change means, whether that’s pre-snap or at the snap. Are we sure the Ravens’ secondary and second-level defenders are turning up to the meetings?

Patrick Queen (#6), the team’s top off-ball linebacker, was drafted in the first round to be a move piece, the kind of new-fangled off-ball ‘backer who could play in space, who, more than likely, was brought in to deal with all of the spread fun-and-games being run in Kansas City, has been a sinkhole in the middle of the defense. Once a team decides to run downhill at Queen, the entire house of cards collapses.

Getting off blocks was always a sticky area for Queen at LSU. In Dave Aranda’s linebacker-friendly scheme, Queen was kept clean by design, with big bodies eating up double teams upfront and Queen left free (out of the run fit, often) to rally to the ball. In a pro-style defense (a term we rarely use compared to its offensive counterpart but that should become a staple of the football vernacular), he’s been a mess.

Rarely will you see a team so consistently out-leverage itself in the run game on first down alone. After six weeks of barfy run defense, Martindale and co. brought back linebacker Josh Bynes to bring some order to the chaos.

Bynes has been a mini revelation. He can sift through levels in the front. He plays hard. He hits the right spots. He plays team-construct defense. He attacks downhill. He – stunningly – can tackle. Who knew that could help!

After starting the year with the Panthers, Bynes is back in Baltimore. He started the year on the Ravens practice squad. By week five, he had played just 13 snaps. By week seven, he was leading the defense in snaps.

But that gives Martindale issues on later downs. Getting Bynes on the field has necessitated a more traditional flipping between packages – you play the early downs; you play the passing downs. The group remains mobile and versatile (Martindale’s overall goal) but they’re more predictable than before. In order to add a run-plugger on early downs, he’s had to sacrifice some of the multiplicity that could make the Ravens an effective group on every down.

The offense isn’t supposed to know what’s coming when, in theory. Each package should be malleable enough to hold up against the run and send pressure against the pass. Just like Arizona.

Static is death to a defense in 2021 against high-powered offenses that shift from multiple tight ends sets into spread looks on a snap-to-snap basis. Defenses must counter with some duplicity of their own: different packages, different pressure groupings, and different formations and fronts on different downs. You might run base with a vanilla cover-1 on third down and a quirkier fire-zone design on first down. The possibilities are endless!

That’s the ideal Martindale has been shooting for. The team’s lack of oomph vs. the run-game from lighter packages has compromised the overall integrity of the group he’s trying to build.

Back to those pressure looks. Martindale’s answer to any and all defensive issues has long been: More pressure.

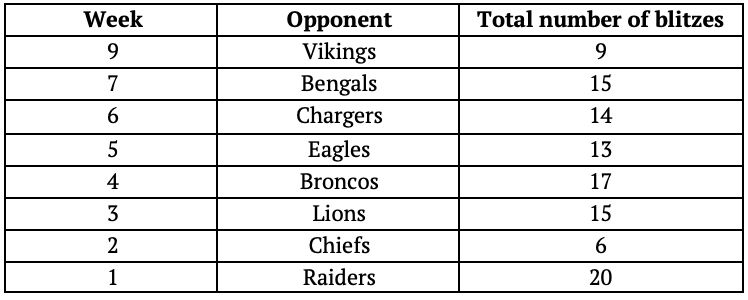

If some pressure is good, more must be better, right? The Ravens blitz at the rate of an eight-year-old hammering their way through a Madden career mode. In looking for a fix to issues, beyond bringing back Bynes, Martindale has settled on an idea: Blitz the hell out of the backfield. Run. Pass. First. Third. Whatever. If the ball is back there, he’s sending extra defenders to go get it.

Sunday against the Vikings represented only the second time this year that the Ravens blitzed on ten or fewer snaps, the only other instance coming against Patrick Mahomes and the Chiefs – the Ravens charting the same course as every other defense vs. Mahomes and the Chiefs sputtering offense this season. 8 of the Ravens’ 15 sacks this season have come from off-ball defenders. That percentage of sack production is fine: Being a blitz-centric defense is baked into the roster construction. The Ravens got lighter in the middle and the perimeter exactly because they want players to be able to line up in multiple spots, to help the team deal with motion and to allow them to attack from different angles.

Still: The Ravens are 24th in adjusted sack rate. It’s fine to have the off-ball players occupying over 50 percent of the production provided the overall production trends closer to the middle-to-upper portion of the league than the bottom.

Only three Ravens defenders have totaled more than 20 pressures this season: Odafe Oweh, 24; Calais Campbell, 21; Justin Houston, 20. And a whole heaping of that production has been concentrated in specific weeks: Campbell was a one-man wrecking crew against the Broncos, posting a seven-pressure day. Against the Chiefs, Chargers and Vikings, he delivered a trio of goose eggs.

(A spoonful of that production has been thanks to crafty designs from Martindale, I hasten to add. These are not all dip-and-rip, win one-on-one pressures. There are free runners all over the place in obvious passing situations)

Houston and Oweh have been more consistent, but they remain sub-package edge-rushers who’ve been one of the main sources of consternation in the run-game: Martindale has to send overload pressure off the edge because neither is winning, consistently, one-on-one and breaking the backfield.

For Martindale it’s a simple problem: he doesn’t have the coverage pieces to live in a five or six-man rush world; but there isn’t enough juice up front to live with a four-man pass-rush. Something has to give, and that’s usually yards and points.

Add to that: The communication issues extend into the secondary. Not a week goes by without the ball flying over the heads of a pair of defenders as they stand and point at one another, arguing over who exactly made the crucial mistake.

Again, simply getting aligned seems like a challenge:

Excuse me while I go and throw my laptop into the river. Let’s make sure we get everything right here:

DeShon Elliot (#32), the team’s safety, is down at the line of scrimmage, communicating with the sideline and/or his teammates, unsure of the call and unsure of what the defense should shift to.

As the ball is snapped, Elliott is turned around trying to signal to change the call

The Ravens run a zone-pressure, with two mugged defenders dropping out into the SAME SPACE.

DESHON ELLIOTT IS IN THAT SAME ZONE.

THREE DEFENDERS IN ONE ZONE.

Marlon Humphrey, the team’s boundary corner, has a deep middle-third zone

Inside Humphrey, the team’s centerfielder, Chuck Clark (#36), has a deep middle-third zone.

Justin Jefferson, one of the finest receivers in the league, runs a quick-faking out-n-up route, drifting towards the post.

Marlon Humphrey lets him go, funneling Jefferson towards his help.

The help – Chuck Clark – lets Jefferson go to!!!!!

It is, all in all, the single grossest play placed on tape (MP4, really) from any defense this year. The only way it could get any worse is if the ground opened up and Voldemort started blasting cruciatus curses left and right while the sound system belted out Now That’s What I Really Call EDM Volume XI.

This is not a one-off. The Ravens’ zone-pressure designs have rarely been as air-tight and coordinated as needed in the secondary.

But there’s not much Martindale can do at this point. This is who the Ravens have decided to be, and much of the schematic makeup is not only sound but tracks well with the evolution of the league. This is what defenses are supposed to do, stylistically, in 2021. This is what a defense is supposed to be, at least in the regular season.

Things will get stickier in the postseason. This stuff just won’t cut it against the best teams in the playoffs. The Rams knew their own brand of blitz-heavy defense was ripe for the pickings against the best and brightest quarterbacks in the game. If you can’t get home with four – either through four quality pass-rushers or a steady drip of wonderful zone-pressure designs – you’re in trouble.

The Rams’ underlying pressure numbers are good. Their pressure profile, however, worried the team’s top brass. The negative plays they have generated this season on early downs have – similar to the Ravens and Cardinals – come with five and six-man blitzes or five-man pressures. To keep that up against Aaron Rodgers, Kyler Murray, and company in the postseason is a big ask. You probably need to live in extended stretches with a four-man rush. The Rams knew they didn’t quite have the pieces, and so they went and acquired Von Miller.

Martindale has been given no such toy to work with to freshen up the team’s profile. There were signs of life from the group in the second half against the Vikings. They stone-walled Minnesota on a batch of crucial third-downs and were able to limit explosives as the game wore along. Still: the first-half performance, off a bye, against one of the league’s most plodding, predictable offenses, was borderline embarrassing.

The Ravens have the fourth-best odds currently to win the Super Bowl, per Football Outsiders. That is almost exclusively thanks to Jackson.

The ceiling for this team should be that high. Even now. If the defense can elevate from awful to competent on first downs, that’s the kind of leap that could have a real long-lasting impact. It’s then kind of game-changing leap, frankly, that isn’t available to other teams who profile as genuine contenders if they make the playoffs. Other teams are looking to improve on the margins, not overhaul one side of the ball.

But that’s not the kind of leap teams generally take after the mid-point of the year. Defenses stink on first down because, well, they stink. Either the players stink or the scheme stinks. Or both. There’s not much else to it.

The Ravens do have talent, even with all the injuries. And Martindale remains on the cutting edge of where defense is at and where it’s going. But time is running out for the thing to coalesce. This should be a defense that compliments Jackson and the offense, not one that caps its potential.

There is no one answer for Baltimore -- only a bunch of little ones. The Ravens have to find some, now.