Ryan Leaf has found peace

"My name is brought up every April…don’t be the next Ryan Leaf. I didn’t realize how much it would affect me mentally, so much so that I was willing to numb my whole life away."

Ryan Leaf was called every name in the books during his short-lived NFL career and the dramatic downward spiral that followed. But a couple of weeks ago, Leaf’s wife referred to her husband by a term never before uttered about him. She called him a workaholic. All Leaf could do was smile.

Being a workaholic is by no means an indicator that Leaf is ready for a victory lap. But given where he’s been and the black holes he’s dug out of and where he should be, he will take it.

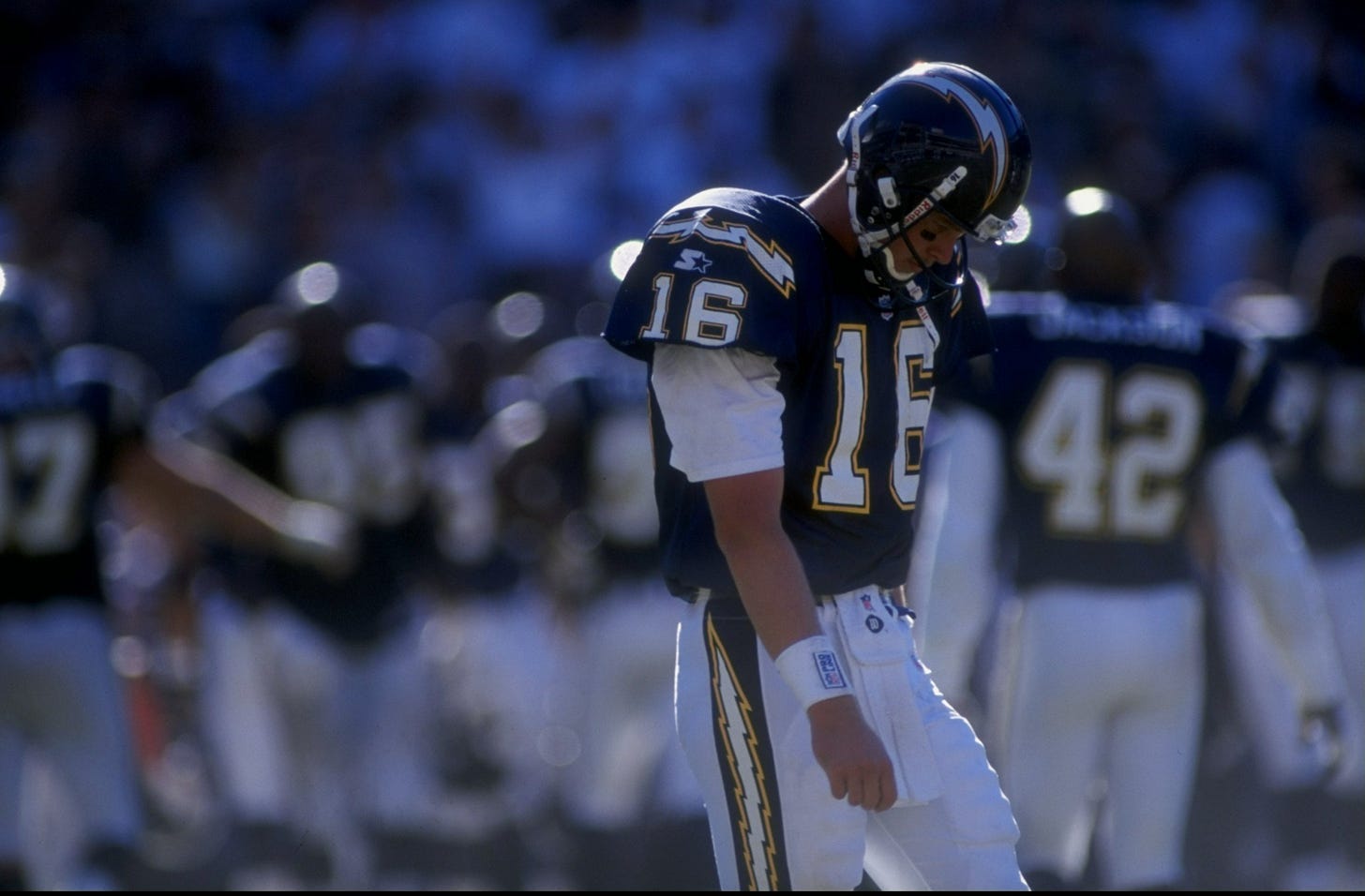

Everyone knows Ryan Leaf. A Montanan by birth, Leaf would develop into a record-breaking superstar at Washington State and finish as a Heisman finalist and first-team All-American. Salivating at Leaf’s extreme arm talent, the San Diego Chargers took Leaf second overall in the 1998 NFL Draft, following a little-known quarterback named Peyton Manning. Their paths immediately went in polar opposite directions.

Manning soared and Leaf flopped. Marred by immaturity, injury, and undiagnosed mental illness, Leaf self-imploded his NFL career over the course of four years. After quitting, Leaf turned to Vicodin to mask his pain. It was 2012 when he hit rock bottom and was arrested twice in his hometown in Montana for illegal possession of drugs and for violating his parole for the first arrest a few days earlier.

Leaf would spend three years in prison. He went in a misguided, selfish abusive, addict and exited clean – but not sober.

“A sober life is a lifestyle and something that must be intentionally worked on every day,” is Leaf’s mantra.

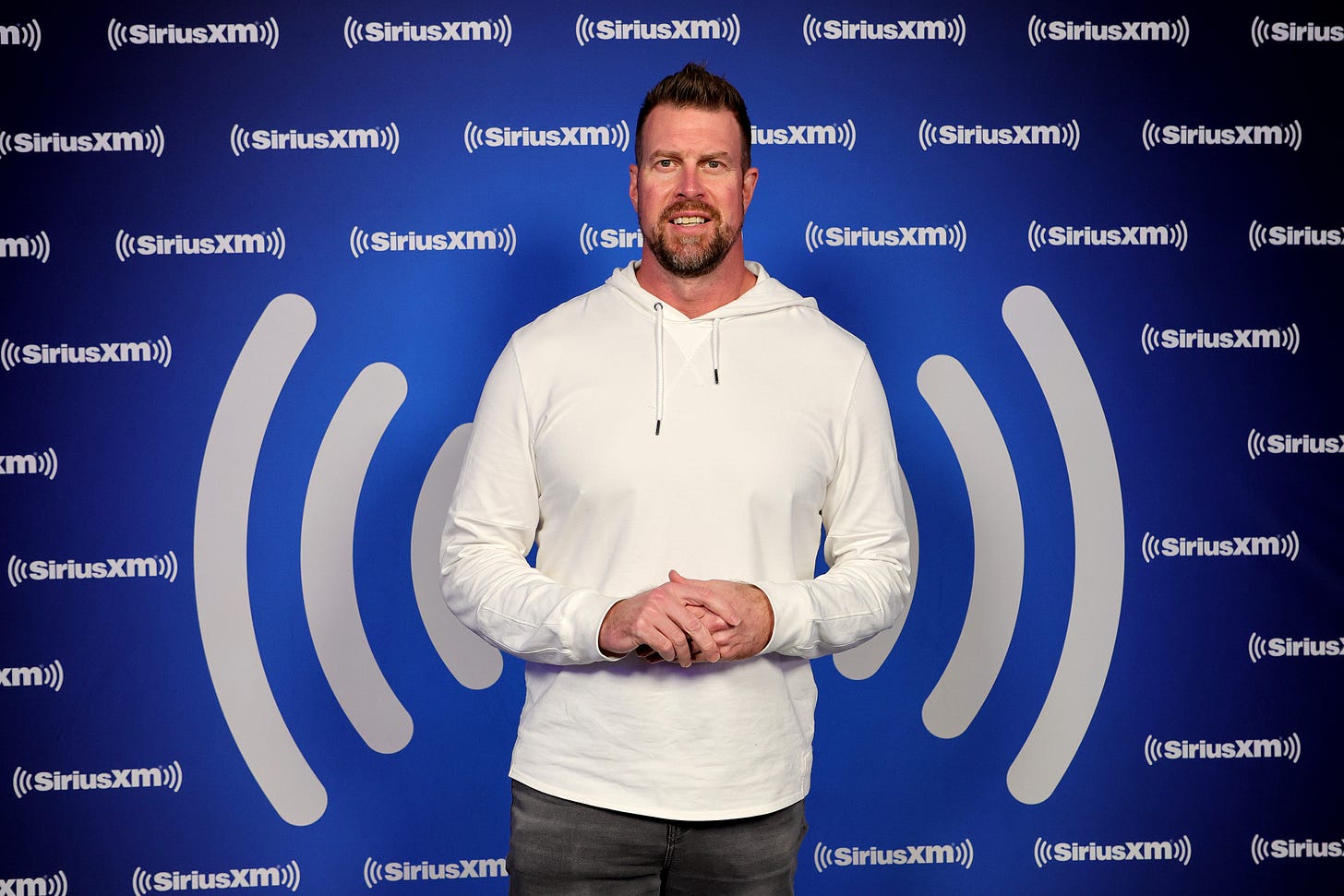

Leaf’s transformation after prison was rooted in his newfound ability to be of service to others. It started in prison as a reading tutor and has extended to post-prison life through fellowship and sharing his story – he recently completed a tour in Alabama working with substance abusers on wellness strategies. Leaf also has a burgeoning second career as a college football and NFL broadcaster. He hosts a daily podcast called The Straight Line, has done work with ESPN, and hosted shows for SiriusXM. So yes, Leaf is officially a workaholic.

He also has more clarity about his mental issue and the issues that will always plague him. Not every day is a win and he’s still fallen on major issues from time to time, including a domestic violence arrest in 2020.

Leaf is acutely aware of his flaws and unlike his earlier self, not trying to mask them. In the latest Afterlife, the former quarterback chats extensively about how early success arrested his emotional development, being tethered to Peyton Manning, his darkest days, and how he found success in his second act.

Melissa Jacobs: We’ll take a lens to the past in a second but first, the present. What made you want to get into broadcasting?

Ryan Leaf: When I got out of prison, I had no idea what I was going to do or where I was going to go. I didn’t want to do just a job to get a paycheck, I wanted it to be something I would love that would also be purposeful. So I put together three things. The first was that I used to make the highlight videos for the team when I was at Washington State, and I love seeing music set to TV and movies. I looked up how I could be a sound editor, so I applied and got accepted to a school in Phoenix that specializes in that.

Then when I was in prison, I got to see firsthand the hand of justice around nonviolent drug offenders. And there was this young man named Shon Hopwood who had been incarcerated in Nebraska and started helping inmates with legal issues while in prison. He became a lawyer when he got out. He passed the bar, clerked for a Supreme Court judge, and now is an assistant professor at Georgetown. I got in touch with him, took the LSATs, and started applying to law school.

And the third thing was broadcasting. I saw what Kirk Herbstreit and Joel Klatt got to do and I thought that was the best job in the world. I reached out to FOX and then I reached out to Kirk and those guys and asked if I could shadow them. I wanted to see if I could be good at it because at that point football in my eyes had become really toxic. That was me projecting. Football wasn’t toxic. I was toxic. But Kirk let me shadow him that fall, and I came away answering the two questions. I could do it and be good at it.

But I had to work my way. An acquaintance of mine in Houston, David Gow, who owned a bunch of stations, gave me a Saturday afternoon show that didn’t pay me anything. Instead, they let me use the recovery community that I was an ambassador for at the time to be the title sponsor. That was my payment.

I did that all fall while also shadowing Kirk. Then Jay Glazer put me in touch with his buddy Steve Cohen who was the head of Sirius XM radio. They were starting to add conference channels and after we became friends, he called me up and said he had a daily Pac-12 radio show he wanted me to head up.

From there I did anything that was offered. It also helped when I showed up at the Super Bowl in San Francisco and told my story on radio row. People saw I was articulate, knew the game and was willing to work my ass off for it. I learned in prison not to take anything for granted and to be grateful for anything that came my way and that’s where it all started Now it has gotten to a point where there isn’t anything I haven’t done.

MJ: You showed your gratitude on December 3rd, 2022, on Twitter announcing you had been sober for exactly 8 years. What does being sober actually mean?

RL: December 3rd, 2014, was the day I walked out of prison with nothing, and I mean nothing. There was no Mickey Mouse waiting for me. I had no idea what life would hold, just that I had to put one foot in front of the other.

I was clean when I got out of prison, but I wasn’t sober. That’s a mind, body, and soul thing, I think. That’s the life I try and lead now where you are open to criticism. You don’t change, the behaviors are still there. You constantly have to work at it. I live life day to day, sometimes hour to hour. That’s sober life. So is humility and understanding you’re a flawed human being just like everyone else.

MJ: Let’s reflect on how you got to a sober life, starting from the beginning. How old were you when you started playing football?

RL: That’s a better question for my mom but from a very young age I was running around the house as much as I could in a Steelers helmet and Louis Lipps jersey. I’d set 2 minutes on the microwave timer and run two-minute drills around the house.

I started playing organized football in 3rd or 4th grade, playing flag, and didn’t wear a helmet until I was in 7th grade. My dad was a quarterback in high school and never lost a game, but football was never anything forced upon me.

Basketball was actually more my thing, and I wanted to be a professional athlete and thought I could do that with basketball.

MJ: When did you know you were good enough to be a professional athlete?

RL: When I was 13, I realized that I was being treated differently and put on a pedestal because of what I could do. I was just head and shoulders more talented than everyone in my hometown and the whole state of Montana.

I also think about that as arresting my development, where I didn’t really grow many life skills because I could get away with a lot of stuff just from being a great athlete.

So around 13 is when I knew, but I don’t think my family even figured it out until that final year before I was drafted. They were like, “oh my god, this actually may happen.”

MJ: You have an incredible career at Washington State, leading the team to its first title game and being a Heisman finalist. What’s it like to be the big man on campus? Where’s your ego at this point in your life?

RL: It was pretty sizable but also, I was an egomaniac with a self-esteem problem. As a player I knew how great I was. As a person I was so fearful of being rejected and my way of countering that was to be the best and win. A lot of people could dislike me, and they did. I grew up in Montana, and I wasn’t what they wanted me to be. My heroes growing up were the Fab Five. Jalen Rose was my hero not Joe Montana. I come from a very white and conservative place. I had the shaved head. I had the basketball shorts down to my knees. Pierced ears.

I felt pretty resentful of how I was treated by people. I was shamed when I was younger, and I would carry that as a chip which ultimately would cost me because I wasn’t willing to forgive people. My hope was to rub it in everyone’s face

MJ: You declared for the NFL Draft after your junior year. Was that a hard decision?

RL: It wasn’t. It’s one I look back on now that I regret only because I know what happens in the future and how I behave and how I’m ill-prepared to deal with failure. But it wasn’t hard at all, I knew I was going to be the first or second pick in the draft and we had just accomplished so much at Washington State. The only things we didn’t do were win the Rose Bowl and win the Heisman Trophy. Those would have been very hard to do since we lost 26 seniors.

But staying would have done a great amount in preparing me to deal with failure. The microscope would have been on me so much that year and if I didn’t deal with failure well at least it wouldn’t have been on the actual biggest stage in the world.

MJ: Had you had any major failures up until that point?

RL: No, I won a championship at the high school level. I mean, there were some failures along the way, I just didn’t realize it, and I didn’t realize how much support I had from people. The only people who really saw how I behaved and how I dealt with failure were my family and probably my coach at Washington State, Mike Price. He was great at bringing me back up when I was down and getting the best out of me.

But I wasn’t self-aware about it so when I finally did fail in a big big way it was on the biggest stage possible and that was the worst place to experience it and deal with it.

MJ: You were drafted well before rookie contracts were retooled. Did you think anything would have been different for you had you not immediately had over $11 million guaranteed?

RL: Sure, money was a huge part of it. I thought success meant money, power, and prestige. Suddenly, I had all three. We never had money growing up, so I had no idea what that kind of money was like. So the money gave me a lot of power. If anyone was critical, I could just put them out of my life and surround myself with ‘yes’ men. The prestige of being a starting NFL quarterback was everything I ever wanted so I thought I had success, and no one could tell me otherwise. That was a big root of the problem as well.

MJ: Talk about the pressure of the draft process. Colin Kaepernick narrated a scene in his Netflix series last year likening the scouting combine to slavery. Did you feel that?

RL: There’s a little feel to that, but c’mon, we’re doing what we want to do too. I do wish I would have understood how much power I had in that situation. As a possible franchise quarterback, you have more power than you think. At the time you’re thinking, sure, I’ll play anywhere but you don’t understand that where you land is like 80% of whether you’ll be a success. If I understood how much power I had I would have dictated more about what I was supposed to do or where I wanted to go.

Peyton and I used our power in different ways. We didn’t do anything at the Combine. We knew we were the 1st and 2nd picks. It’s the allure of being a top pick. If I were smart, I would have said I wanted to go where Brian Griese went. How he went to the Denver Broncos and got to sit behind John Elway and win a couple of championships. Or like Jordan Love and Aaron Rodgers who had quarterbacks to learn under. I just wasn’t ready. I was physically ready, but to be a great quarterback in the NFL you need so much more, and I just wasn’t ready.

I understand Colin’s viewpoint and his reasoning behind it, of course, and I do think the way the NFL treats its players is incredibly poor. But this was also a choice of mine. I was choosing to play professional football, and I was going to get paid handsomely. I don’t want to sound like a victim, I want to make myself accountable for everything I chose to do.

MJ: Did you and Peyton become close through that process?

RL: Yes, we did. I had our SID (student information director) that final year in ’97 reach out to Peyton’s SID. And we started talking months before the process. We had an idea that we were going to be linked, and we were right. We became friends and have remained friends in the 25 years since. I was lucky enough to be asked to come to his Hall of Fame induction and spend time with his family, and his family has been incredibly supportive and generous with my family. It’s amazing what football can do and how it brings people together for a lifetime.

MJ: Things didn’t do quite as planned. We don’t need to relive all the things that happened with the Chargers but what was your lowest point as an NFL player?

RL: Probably that second year when they hired Mike Riley and didn’t really talk to me about who they were hiring. I wish they understood that Mike Riley and I were like oil and water. It was the worst possible combination you could put in that scenario. And then I was injured the entire year with a labrum tear. I felt lost – like I wasn’t a part of anything. I kept screwing up too. I kept misbehaving. I got suspended one time for yelling at the GM. I was so frustrated. The only thing I ever had to counter back was to go out and play well, and I couldn’t do that.

MJ: Then four tumultuous years later, your career is seemingly over. Did it feel over, or did you think about a way to crawl back?

RL: I always thought it was just a matter of me going out and having a four-touchdown game. That it would be different. Even when I was picked up by the Buccaneers, I thought it was a new start. Or even a geographic change. Dallas and even Seattle at the end, I always thought there would be a resurrection. I always thought everyone else was the problem, but the problem was me. So everywhere I went was a problem because it was me.

By the time I got to Seattle, I had developed a high level of mental illness – depression, PTSD, narcissistic personality disorder – all these things I didn’t even know existed at the time, so I thought I was weak and lazy and just quit. I walked into Mike Holmgren’s office and just quit rather than tell him all the things I was going through. How I wasn’t sleeping well, how I couldn’t get out of bed. Maybe if I told him, we could have tried to fix it together. But instead, I just quit and assumed I could just disappear and no one would care about me anymore which is the furthest thing from the truth because the internet started blowing up. Peyton is great – arguably the greatest to play the game. I’m considered a huge bust. My name is brought up every April. With social media it’s a huge go-to…don’t be the next Ryan Leaf. I didn’t realize how much it would affect me mentally, so much so that I was willing to numb my whole life away.

MJ: Yes, then your life is marred by an addiction to painkillers. When you’re in that dark place of addiction, what happens when you can’t get your fix?

RL: You search for it. You find it. So much so that you’re willing to break the law. That’s what happened to me. Competition was my first drug of choice and when competition went away, I found the next best way to numb myself. I had been searching for that my whole life, how not to feel rejected or feel less than. The medication I was introduced to while playing and dealing with orthopedists, I knew that worked. I knew it worked for my physical pain, and it certainly did the job for my emotional pain. That’s what I was searching for every day until finally the sheriff’s department came and saved my life.

MJ: Was there any thought about actual medicine for depression or anxiety?

RL: I never got diagnosed so I didn’t even know it existed. I used to think that people doing that stuff were crazy people, insane people. It’s because of the stigma that existed. It’s gotten so much better, but it still exists. I thought it was weak, and I was a big, strong football player. I didn’t need help from anyone. I started self-medicating and not through science or brain chemistry, any of that stuff. I didn’t figure it out until I went to treatment and was diagnosed. And I have yet to find someone with a substance abuse disorder that doesn’t have a concurrent mental health disorder which is the foundation of it all. I didn’t know any of this stuff. Football was my identity. That’s all I knew.

MJ: How is your mental health these days? What forms of treatment do you utilize?

RL: I’m not on any medications. They tried to put me on some in prison and I was not having it. When I was out and diagnosed, I just started utilizing fellowship, nature, exercise, food, all the things. I haven’t felt like I needed the medication, I’ve found other healthy alternatives to that.

I do see a therapist weekly. My wife and I go to couples counseling from time to time, not because there’s a problem but because I’m a former NFL player and I communicate poorly. I want to communicate better and be a better father. But as mentioned, I also utilize fellowship like AA and have a sponsor.

And when I go and speak and try and share my story with others, that’s the foundation for getting to a place where I can do all the broadcasting stuff we talked about earlier. I strive to be the best version of myself I can be.

I do believe I’m living with CTE. I think we know what the symptoms are now, and I had a brain tumor that was removed about 10 years ago that I got because of brain trauma. So because of all the missteps and the fact that I’m, I guess, such an infamous person that there are consequences to all that, and I was forced to look in the mirror and deal with all of them. I feel lucky because there are a lot of my NFL brothers who didn’t deal with it and they are no longer here. I realize this is a daily task to work on to get the life of my dreams. I have a lot of gratitude to be in this position.

MJ: So how exactly did you turn your life around in prison?

RL: I didn’t really for 22 of the 36 months I spent in there. I sat on my butt and played the victim the entire time. My roommate, who was an Iraqi war veteran, convinced me one day – I don’t know how he convinced me, I was such a piece of shit in there – to go down to the library and help those who didn’t know how to read learn to read. That’s where it started. Suddenly I was being of service to another human being, and I think that’s the first time I did in my entire life.

I think before I thought what I did on Saturdays and Sundays was me being of service to people. That’s what I thought service was. So that’s what changed. And it wasn’t just going to the library one day, it was going day after day. It’s like going to the gym. You don’t just go one time and then look like The Rock. You must be dedicated and consistent. So when I got out I knew that was going to have to be the foundation of who I was. It could never be about me again, it had to be about someone else.

MJ: Despite all your progress, the public still refers to you as a draft bust and warns, as you said, of becoming “the next Ryan Leaf.” I assume not everyone is terrible but how do you navigate social media?

RL: It’s like any human being. We can get a thousand compliments and one criticism, and we focus on the criticism. It’s human nature. And people are horrendous. They’ll say some of the worst possible things. especially on social media.

For a long time, I took the high road and, for the most part, I still do. But I’m also at a place in my life where I like who I am. So, I’ve started flapping back a little bit. I also think it’s an opportunity, whether they choose to accept it or not, to show them the mirror of how they’re behaving. I had people show me that mirror along the way and it helped me – my prison roommate, my sponsor, my wife.

Maybe there’s no one behind the anonymous post but if there is and I show them how they behave maybe they take a look. I’ve had people apologize for things like that, but of course, most people double down when they’re offended. But it makes me feel better for standing up for myself and not just getting beat over the head like I have my whole life. It doesn’t cost me anything and maybe it will help someone in the long run.

MJ: When do you feel the healthiest now, the most at peace?

RL: It’s usually at night when I crawl into bed. I think my wife gets pretty sick and tired of me telling her how much I love our bed and how it’s so comfortable, but she doesn’t have the perspective of having slept on a concrete slab for three years. There’s a lot of gratitude there. I know I’m laying my head down and it’s another sober day knocked off the list.