Sean McVay & Matthew Stafford: The NFL's most compelling marriage

Stafford is the quarterback McVay has been waiting for. But to maximize the Rams' potential, the coach must meet his quarterback halfway.

The Rams are excited about Matthew Stafford. Like, really, really excited.

Glance through any preseason comments and you’re hit with a parade of enthusiasm. Stafford has it. This is all going to work. He elevates certain aspects of the McVay system. With Stafford, things don’t just feel different. They are different. Not just on the field, by the way, not just within the team’s offensive structure, but throughout the building. Everyone is that much brighter; there’s a bounce to the place.

Having a high-end starter will inspire that sort of buzz amongst a group of players who expect to be holding up the Lombardi come February. “When the pros are saying ‘Ooh, holy blank,’ you know it’s a pretty good,” McVay told NBC’s Peter King during the team’s first week of training camp. “Those who know, know.”

The Rams gave up a bounty to land Stafford, forfeiting what precious few draft assets they had in a bid to cash in on their star-laden core. There aren’t a whole bunch of moves that can be fairly categorized as ‘Super Bowl or bust’, but shipping out two first-round picks, a third-round pick, and the former first overall pick, Jared Goff, represents an honest-to-goodness all-in play. Anything other than a championship will be seen as a failure.

The excitement surrounding Stafford is valid. For years, the former Lions’ signal-caller has been underrated as both a pre- and post-snap weapon. Too often, he has been shoved into a box. It’s his physical traits that dominate the discussion: His arm strength and the ability to push the ball downfield. But that undersells the parts of his game that have turned him from a highly volatile, downfield bomber into a consistent top-ten performer.

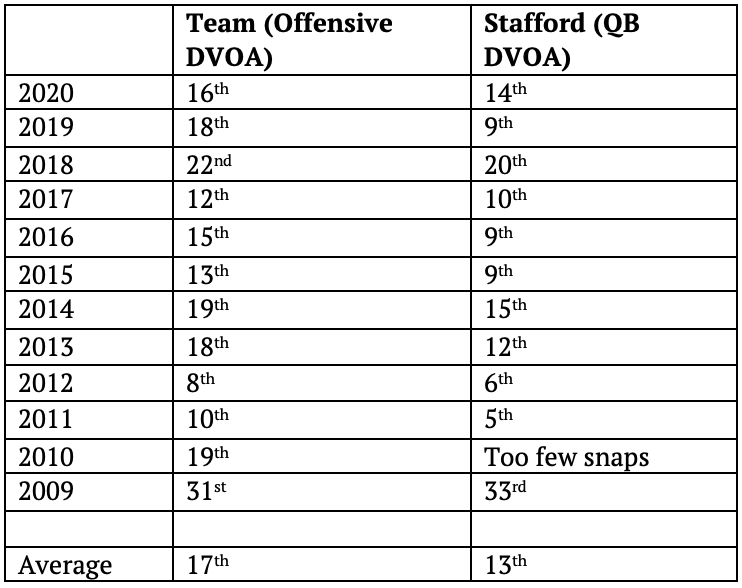

In Detroit, he was relied upon to drag blah talent and unimaginative schemes to an area somewhere near respectability. Over the course of his ten years with the Lions, the team finished in the top ten in offensive DVOA twice; Stafford finished in the top ten of quarterback DVOA (a measure of a player’s down-to-down efficiency) six times. When Stafford was treated to an elite talent– Calvin Johnson – he finished fifth and sixth in Football Outsider’s efficiency metric.

(Johnson had 218 (!) receptions combined in 2011 and 2012 when the Lions ran a pure isolation-based — read: Johnson-based — system. He finished first in DYAR (total value) in both years.)

When Stafford and the Lions were rolling — really rolling — they followed the Peyton Manning template: condense to expand. The pre-snap formation would be tight, offering Stafford’s receivers plenty of space to run into. Get the ball out quick and give receivers a chance to make a play downfield or after the catch, that was the idea. In all but one of his top-ten DVOA seasons, Stafford was playing in a system that relied on his intellect pre-snap, rather than in a system with a whole bunch of post-snap variables.

At the end of his Lions run, though, things had shifted. Detroit followed the spread-out boom. They would get as many eligible receivers down the field as possible, relying on Stafford to sort it all out, move in the pocket, and then get the ball downfield.

In L.A, Stafford walks into the league’s ultimate condense-to-expand offense, one built to win through play-designs, with the ball coming out on-time and in-rhythm rather than relying on receivers to win a ton of isolated matchups.

McVay leverages confusion into easy yards and touchdowns. Stafford plays with little artistry, relying on his pre-snap control to get to the best possible look, which should allow him to get the ball out in double-time or at least give him a strong indicator of where he’s going with the ball before he drops.

Much of the early Stafford-to-the-Rams discussion centered, once again, on Stafford’s ability to push the ball vertically. And that will be crucial to any success the team has this season. But Stafford has always been more than the power-throwing cliché that has followed him throughout his career.

And it’s that divergence in styles that makes the McVay-Stafford marriage the most compelling of the new season.

One of the most under-discussed parts of Stafford’s game is his pocket mobility. Playing behind a steady crop of shaky offensive lines during his time in Detroit, Stafford became adept at shaking and moving within the pocket, manipulating space, buying himself time, and crafting windows in order to deliver the ball downfield. He would hold it and move, then hold it and move some more, waiting for a receiver to give him something to work with.

One of Sean McVay’s complaints about Jared Goff was his eagerness to get rid of the ball. When the Rams offense was on — think of that MNF game against the Chiefs — there was a true downfield element. Run. Run. Shot. By design, it’s not much more complicated than that.

Goff is a talented deep-ball thrower, but he can get skittish in the pocket, wanting to release the ball a couple of beats before he takes a shot — perhaps dating back to his college days, where he was the most hit quarterback in the country in consecutive years.

Stafford is more decisive than Goff. If he’s getting rid of the ball, it’s gone. If he’s waiting to take a shot downfield, he’s more adept at moving, climbing, slipping, and sliding to earn a little more time before he releases the ball.

Goff’s inability to shift in the pocket became a more pressing issue the longer McVay and Goff worked together. It wasn’t that the quarterback wasn’t developing; he was regressing. At Cal, Goff had a knack for navigating clutter. Cal ran a bombs-aways style on offense, with all five eligible players out on every play. It was left to five linemen to block however many defenders the defense sent. One issue: his line stunk. Time and again Goff was tasked with dropping, tippy-tapping around the pocket, and trying to find somewhere – anywhere – to get rid of the ball before he felt a crunch.

As a passer under pressure, Goff was pretty special at the college level. He had an innate sense of how and when to move. He could dance up, sideways, or back. And he always played with light, choppy feet:

What he didn’t have was the slip and slide that is preferred at the pro-level, the exaggerated slide and jump up and through the pocket. There’s no use for three or four steps where one or two will do.

Goff’s rookie year in the league was a mess. In Jeff Fisher’s mundane offense, he was tentative. His dancing feet were stuck in the mud: he dropped, he sat, he looked, he got hit. Sacks that could have been avoided became inevitable. And the more shots Goff took at the NFL level, the more those tidy chop steps vanished. McVay was able to build in more mobility through play-action and boot-action designs, but Goff’s inability to master the art of the stick-slide-climb-throw compromised the Rams’ core concepts once the league got to grips with all of the pre-snap fun-and-games that McVay was running. It proved costly:

Manipulating the pocket, they call it. Or pocket mobility – take your pick. It’s the ability to navigate those cluttered lanes, to make small movements that create decent throwing angles. To turn a dead play or negative play into, potentially, a significant gain.

At the end of his time with the Rams, Goff became consistently rooted to his spot. You could see his indecision seeping through the screen:

It’s a key reason why Goff turned the ball over 46 times over the past two years, throwing 29 interceptions.

Stafford is different. He crafts time and throwing lanes. He delivers accurate balls from funky arm angles. He slips and slides:

There is a Brady-ish feel to it all (still the league’s best stick-slide-climb thrower). It takes courage to climb through the pocket, to show patience as snarling pass-rushers beat down, to have trust in your linemen or your own timing that if you climb at just the right time, those pass-rushers will go flying by. Instinct says to get the ball out now. But climbing buys time -- and time makes all the difference:

Stick with that through the endzone view.

His offensive line crushed all-around him, Stafford was able to wriggle through the thinnest crease – his right tackle ended up flying by his left shoulder. With the aid of a switched-on guard who was able to get just enough on the Niners looping d-lineman, Stafford was able to climb the pocket to rip a fastball downfield. What should have been a negative play wound up finishing inside the Niners’ 20-yard line.

Stafford’s ability to shuffle, climb and fire has consistently rescued should-be negative plays. Stafford finished with a 91.8 passer rating against pressure in 2020, per ProFootballFocus. Goff, a measly 50.0 passer rating.

That will work for McVay. “When you really study him,” McVay told King for his Football Morning in America column, “you see the intricacies of the quarterback position. His ability to navigate the pocket, his movement, his feel for the rush, his ability to keep his eyes down the field. And then to exhaust your progression against that rush, that’s something in the NFL that a quarterback just has to do.”

McVay is rightly lauded as one of the league’s top schemers. He gets receivers open through design, as the saying goes. And while those kinds of plays often come on-time and in-rhythm — hit the backfoot, get the ball out — McVay likes to work in plenty of slower-developing concepts, which can be just as effective (if not more so) provided the quarterback has the confidence and the courage to stand in the pocket, or the ability to buy himself more time by manipulating the pocket to avoid the rush.

Stafford isn’t a pocket dancer. He’s slick. He wiggles and shuffles. And his eyes are always — always — downfield.

It’s the area where the McVay-Stafford marriage has the most potential: unlocking the vertical passing element that McVay craves but that Goff wasn’t able to deliver full-time. But it’s also the area that will be in direct conflict with Stafford’s previous life as the Lions Do-Everything LOS commander.

It will take time for the coach and quarterback to adjust to one another, but there are ways that McVay can offset concerns.

For as smart and savvy as Stafford is at manipulating the pocket, his downfield coverage recognition doesn’t rise to the level of a Rodgers, Brady, or Wilson. He’s good, but not always great; he likes to lock in on what he wants to do and then deliver it. McVay’s system calls for more subtlety, not just feigning your eyes one way and then chucking it the other. It calls for really reading deep progressions, in watching as man-beater concepts unfurl themselves 15 to 20-yards downfield, and in being able to adjust on the fly as the Rams’ receivers adjust their routes depending on the coverage and the leverage of specific defenders. Every intermediate-to-deep play design has both option-elements and on-the-fly adjustments, a significant difference for a quarterback who has spent the best years of his career in systems with set post-snap downfield designs.

(With the Lions, Stafford would chop and change pre-snap – be it one-off routes or entire plays)

All NFL offenses have leveraged-based options routes in short-yardage situations (the defender goes this way, I go that way), but having such designs on shot plays is what makes the Rams passing game so difficult to defend and complex for its quarterback to read.

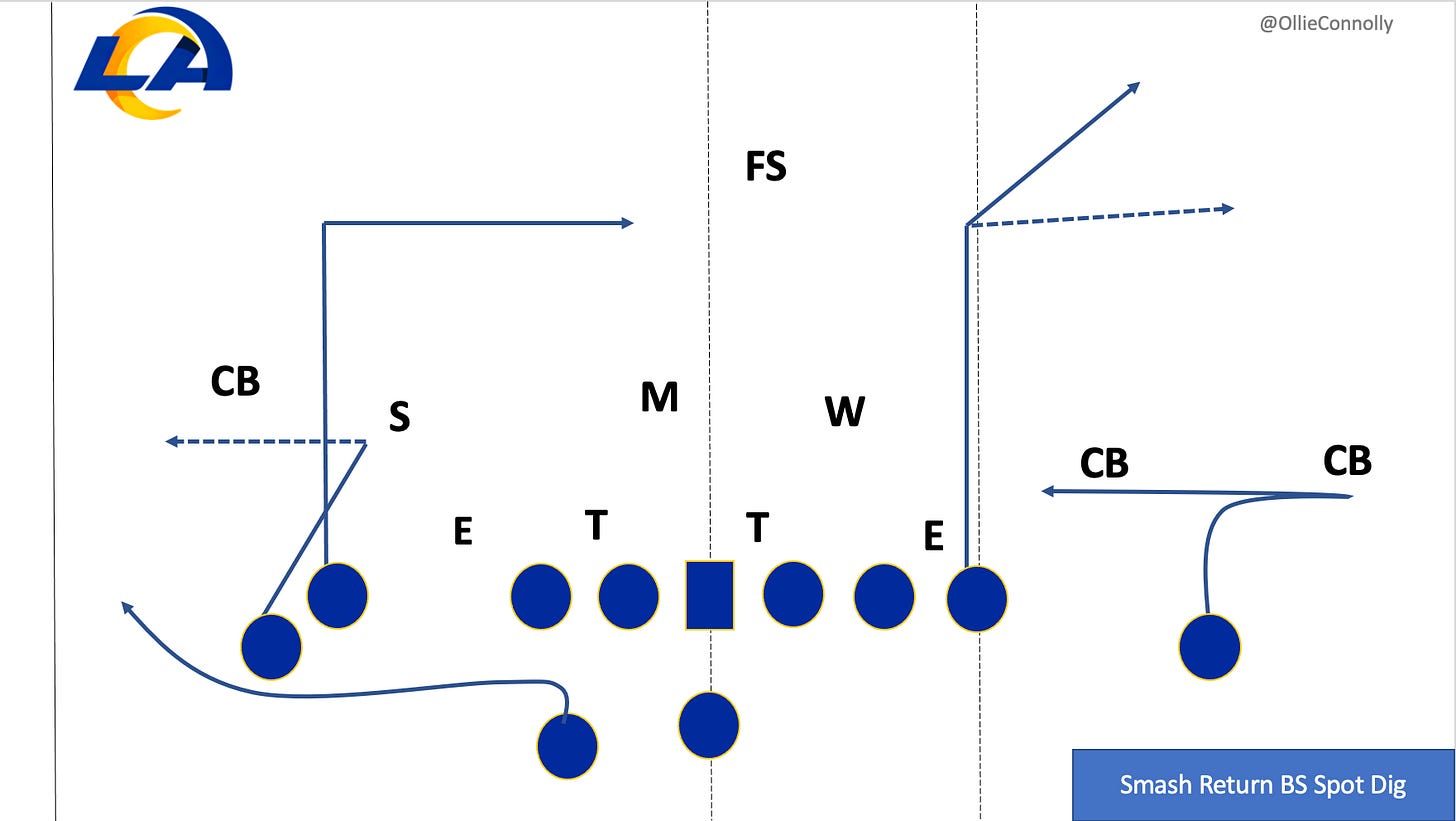

McVay’s base concepts are built from the triangle philosophy (the crossing of routes forming a triangle), as with any modern passing offense. But the vast majority of those concepts come with options deep in the receivers’ break, hoping to build in some man-beater concepts down-the-field, as opposed to the traditional way of just trying to disrupt man coverage at the line of scrimmage or by the first-down marker.

In fact, what has made McVay’s passing attack so novel and effective is that he will build both into the same concept. There will be the traditional man-beater concept at the line of scrimmage, with receivers stacked up together and switching their releases, with option routes tagged on deep down the field, sometimes with a second crisscrossing concept built-in further downfield.

The intent is to make things blurry on the back-end: to have receivers criss-cross deep downfield, hopefully springing a receiver open for a big gain; or, if the defense is in zone look, to take advantage of the ‘find grass’ principle. See space, run for space. But do it down the field so that if there is space, it can lead to an explosive play rather than a 10-yard pickup.

It also allows the Rams to run the same play over and over again but with different outcomes. Meaning: the defense reads it differently. One design could look like four or five different plays. Maybe more, depending on the specific play. For everyone single play McVay’s offense is prepping for, the opposing defense is plotting out four or five.

It will be a learning curve for Stafford. It’s a lot to pick up. And it requires chemistry between a quarterback and his receivers. But McVay can help to dampen any concerns by building in more of the isolation concepts that Stafford thrived on at different points during his Lions career.

Jim Bob Cooter’s time as Lions OC went haywire at the end. The Lions became too predictable. His group committed the cardinal sin: tipping their plays. But during Cooter’s time as Stafford’s quarterback coach and offensive coordinator, Stafford finished in the top-ten in quarterback DVOA three years in a row. The fourth year, when Stafford collapsed to 20th in DVOA, was when teams figured out Detroit’s tells.

The concepts were and are fairly rudimentary. One player – a mismatch piece: a big-bodied or dominant receiver or a flexed out tight end – was split away from the formation and isolated to one side. On the other side of the field, the remaining receivers spread out. With Cooter, the Lions used extreme splits, isolating the solo receiver into the boundary. The goal: to give Stafford similar looks against both two-high and single-high safety looks. When Cooter left, the Lions became a touch more traditional. Yet Stafford remained extremely effective on isolation throws.

Kenny Golladay helped. Stafford was once again relying on a big-bodied receiver isolated on the backside (albeit from more traditional formations). Here’s an example:

It’s as basic as football gets. Stafford reads the safety. If the safety rotates to the field or holds his position in the middle of the field, Stafford can take the one-on-one shot to Golladay. If the safety moves to double Golladay, Stafford has a series of one-on-one matchups on the other side of the field.

Working in some of the Stafford isolation plays into McVay’s richly layered approach will help ease the quarterbacks learning curve.

In 2020, on isolated looks to the left, Stafford averaged 11.4 yards per attempt, four yards ahead of the league average; on isolated throws to his right, he averaged 10.8 yards per attempt, three yards above the average — and that in a non-iso-heavy system, by Stafford’s standards. By contrast, Goff averaged 9 yards per reception on iso looks to his left and 5 yards per attempt on iso looks to his right in 2020.

In the simplest terms: Goff flows within the confines of a scheme. Stafford enjoys reading it and ripping it, giving his receivers a chance to win one-on-one.

Building in isolation concepts is easy. Being able to take advantage of them is a different matter. You need a flex piece good enough to draw coverage, someone the defense believes is a genuine threat to dominate one-on-one (Calvin Jonson, Kenny Golladay).

You also need a coach willing to relinquish some of his control.

Even within his pre-snap isolation looks, McVay likes to get funky with some kind of play design rather than allow a straight one-vs-one contest between receiver and defender. Take this call against the Bucs, for instance:

Pre-snap, the Rams line up in a 3x1 set, with three receivers to the field side and tight end Gerald Everett isolated on the backside. It’s the classic isolation look; it’s matchup ball. The quarterback flashes his eyes to the boundary. If he likes the match-up, he slings it. If not, he works back to the field side.

Not for McVay. The coach runs a flare motion to the field, with the running back pressing out hard behind the trail of receivers. The goal: to get the Bucs safety to bite on the motion and to spin towards the three-receiver side of the field. From there, it’s game on: McVay runs a tight end screen to the backside, hoping his tackle can fire out quick enough to pin the safety covering his tight end.

The play didn’t work. The screen was sniffed out. Andrew Whitworth, the Rams left tackle, wasn’t able to get out in time. The throw from Jared Goff was a little behind, forcing Everett to head back towards the line of scrimmage. The Bucs were able to cut off the tight end before he could make any real progress up-field.

With a 6-4 tight end matched up against a 5-10 safety, with no extra help over the top and no roamer cutting off a quick, inside cut, the call should have been easy: Everett shuffling downfield and Goff giving his man a chance to go win the matchup.

Instead, McVay overthought it. It was a nifty design, a nice whiteboard play. But it should have been a matchup call: The Rams picked up four yards, but the pre-snap picture promised so much more.

Stafford rinses defenses on isolation plays. The Rams coach would be wise to take a back seat on such designs, allowing Stafford to pick-and-choose whatever he wants depending on the picture the defense presents to him.

Stafford’s best post-Calvin Johnson run with the Lions came when Jim Bob Cooter relinquished any sense of control to his quarterback. It became Troy-Aikman-on-the-Cowboys-like. Stafford was calling the plays. He had complete authority at the line of scrimmage to adjust whatever he liked. The Lions went quick, using tempo and limited personnel packages, gifting Stafford as much time as he liked at the line of scrimmage to tweak and change things, channeling his inner Manning.

More often than not, the Lions would call the same plays with Stafford adjusting the backside route – like McVay and the Rams, presenting a different picture to the defense from the same offensive call — built around a tiny number of possible routes (take-off, deep over, hook, in, out) communicated through hand signals. Stafford would run the same play design to the field side – whatever Cooter had called – and would pick and choose his own route concept on the backside, communicating with the receiver one-on-one.

Stafford should get a similar amount of creative freedom with the Rams. It’s where he’s is at his best.

Last season, Stafford threw nine touchdowns to zero interceptions on throws over 20-yards last season, finishing with a double-take-worthy 123.9 passer rating, a full 23 points ahead of the NFL average. By comparison, Goff finished with a 74.3 passer rating, well below the league average.

Finding a balance between Stafford’s down-the-field isolation concepts and McVay’s carefully choreographed designs will be crucial to the pair’s success together. Neither has to re-imagine their style. Rather, they must figure out how the two ideas can best blend together on a week-to-week basis.

To start with, the Rams will need to find a player worthy of isolating. Gerald Everett is gone, signed by the Seahawks this offseason. Tyler Higbee (who finished fifth in DYAR among tight ends last season) was split out on just 69 plays last season; a fifth of Everett’s snaps (115 in total) came out wide. With Everett now in Seattle, Everett’s flex figure should double in 2021. He’s better in-line and working the middle of the field, but even as a coverage-revealing decoy, he would bring more value to Stafford working out wide than he would as a consistent middle-of-the-field player. How the Rams divvy up the value of aiding their quarterback vs. putting their tight end in the position where he succeeds best will be interesting.

Behind Higbee, there’s little of note: Johnny Mundt played 120 snaps last year, only five of which came out wide; 2020 fourth-round pick Brycen Hopkins was forgotten entirely by his coach when asked about the tight end room on a recent podcast, which doesn’t bode well; Jacob Harris, a fourth-round pick in this year’s draft, has the prototypical weight-weight-speed profile to be a valuable split-out threat. But it’s an awful lot to ask of a rookie to serve as the team’s premier isolation threat.

The Rams’ best receivers – Cooper Kupp and Robert Woods – are excellent precisely because they’re not isolated; their inter-play down the field and their understanding of coverages are what has made the pair so effective.

Adjustments flow in both directions. Find the right balance, and it’s not impossible to imagine Stafford making a Matt Ryan-style MVP run, with the Rams entering December as Super Bowl favorites. But the transition will not be as simple as plugging Stafford into the typical McVay set-up and expecting him to add a bevy of explosive plays, the kind that eluded Jared Goff at the end of his run in Los Angeles.

It will be a push and pull: Stafford working to perfect some of the more sophisticated McVay designs; the coach freeing up his quarterback to play some see-it-hit-it football.

Sometimes things grow stale. The scheme changes and a player becomes lost. Or it doesn’t, and complacency or predictability sets in. Things became stale for Stafford in Detroit. Teaming up with McVay should inspire a rebirth of sorts; the idea of Stafford playing in a system with more motion, shifts, pre-snap goodness, and those traditional McVay quick-game designs is tantalizing. McVay’s side finished 16th and 19th in offensive pass DVOA over the last two seasons. The floor with Stafford should be 10th.

But the floor is boring. It’s the ceiling — the possibilities of Stafford’s efficiency paired with McVay’s explosive designs — that has the staff, players, and fans excited.

The Rams are dreaming big — because they’re always dreaming big. Stafford is the quarterback McVay has been waiting for. But to maximize the team's potential the coach must meet his quarterback halfway.

Synthesize their styles, and the McVay-Stafford pairing could be football nirvana.

Thank you for this. People see one video on the NFL YouTube channel a few years back, and think Stafford can’t read defenses, when he was the one calling plays at the line!