Tears & Beers: How Jackie Smith found himself

What happens when you bleed and sweat and bleed a little more for 214 games, then your world comes crashing down in Game No. 215?

Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from of Ty Dunne’s wonderful book: “The Blood and Guts: How Tight Ends Save Football”. Ty is the best writer/storyteller currently covering pro football. He’s a magical writer; it’s a magical book. In chapter three, Ty talks with Jackie Smith about the tight ends career, legacy, *that* drop, the mindset of the position, and what it means to be defined by your worst professional moment. You can buy your copy of Blood and Guts today at Amazon and everywhere books are sold.

The good times are rolling for Jackie Smith. He’s basically your lovable grandfather from the jump with eighty-two years of stories that twist and turn and always land on a profound point. His vivid memory is rivaled only by a vivacious personality. If Mike Ditka finds his peace at a golf course, cigar in hand, Smith relaxes at a spot like this, Syberg’s restaurant in the St. Louis area, with a twenty-two-ounce beer in hand.

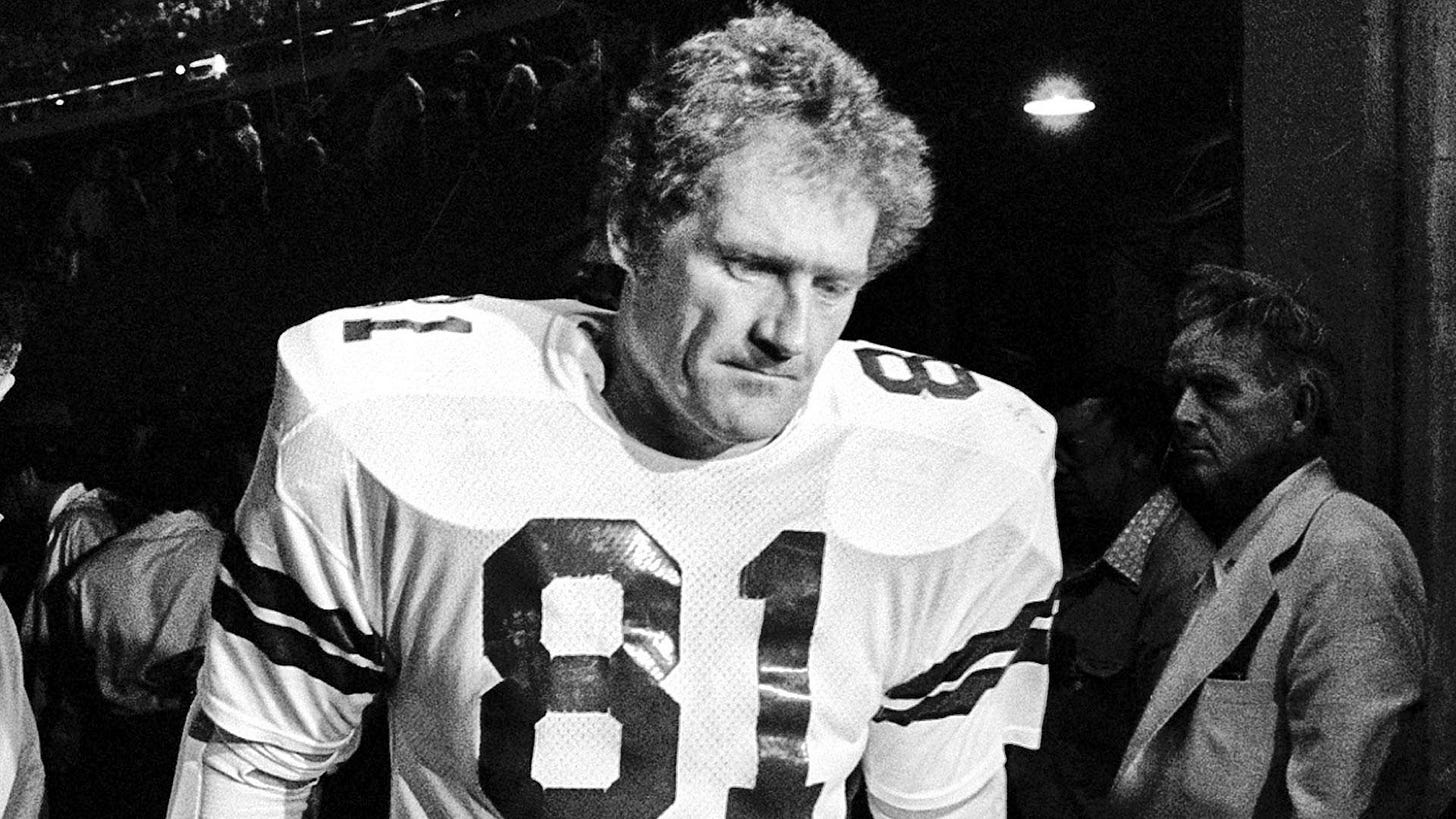

It’s packed. It’s loud. In a perfectly ironed, buttoned-down shirt, the former St. Louis Cardinals great has the sort of gentle eyes and cheeks that are frozen in a thin, permanent smile. What a joy it is for him to detail his rise. Smith was the first tight end to truly emerge out of nowhere — a dirt track in Kentwood, Louisiana — and dominate pro football. He was a bad, bad man who could both run like a gazelle and kick some ass. Yet when everyone hears his name, these aren’t the memories that autoplay. Unless you’re a football diehard who’s at least seventy years old, these memories are forgotten. Chances are, Jackie Smith elicits a totally different moment. A nightmare. At a tabletop nearby, right underneath one of those neon beer signs and televisions that replay Tom Brady highlights on ESPN, sits the elephant in the room. One we cannot ignore. Close friends advise against bringing up the night of January 21, 1979 because they know the pain it brought Smith.

Like Ditka, he dismantled defenses from the tight end position.

Like Ditka, he took a circuitous path to Tom Landry’s Dallas Cowboys in the twilight of his career and, like Ditka, a football was thrown to Jackie Smith in the end zone of a Super Bowl.

The ball arrived, ricocheted off his fingers, and everything changed.

Be it the stakes, the iconic radio call, or the image of his body levitating off the Orange Bowl surface, these scant 5.5 seconds defined the man. And it’s not fair. When Smith retired, no tight end in pro football history had more receiving yards. He was the first of his kind. A star. Yet his legacy was distilled down to one mistake that, in truth, wasn’t fully his mistake. Whereas Ditka overcame his depression to become one of the sport’s most beloved ambassadors of all time, people mostly associate Smith’s name with failure. Imagine if a moment so brief in your profession grew to define your very existence to millions. It wouldn’t matter if you’re volatile by nature or, like Smith, the epitome of southern hospitality. Psychological damage is a guarantee.

So, through a four-hour chat, we ever . . . so . . . gently . . . ease into this subject.

Once Smith is displaced to Super Bowl XIII, he doesn’t hide. He basically orders that elephant an IPA, relives it all, and never breaks that smile.

“I guess they can kill you,” Smith says, “but they can’t eat you. People can look at it how they want to look at it. I did the best I could do. It’s an emotional game for the fans, too. When things like that happen, it’s something to be talked about. The thing that helped me a lot was the attitude I had — I was so lucky to be there. How can you cuss and get upset and be depressed about something that gave your children . . .”

His voice trails off. That tends to happen when his kids come to mind.

Smith reaches into the front pocket and pulls out two sheets of paper held together by a staple. Right here are a collection of typed quotes from one his favorite authors, Ralph Waldo Emerson. For several minutes, Smith is quiet. He reads the prose to himself with pursed lips and striking intensity.

Finally, Smith pauses and recites one quote aloud.

My life is a May game, I will live as I like. I defy your straight-l aced, weary social ways and modes. Blue is the sky, green the fields and groves, fresh the springs, glad the rivers, and hospitable the splendor of sun and star. I will play my game out. And if any shall say me nay, shall come out with swords and staves against me to prick me to death for their fool-ish laws, come and welcome. I will not look grave for such a fool’s matter. I cannot lose my cheer for such trumpery. Life is a May game still.

This is the one that helps most. Asked to interpret what the quote means to him, his voice rises.

“There’s a lot more to life than a freakin’ football game. It’s a wonderful game. But it’s a game. It’s not the essence of life.”

Few have a clue that it took years — no, decades — for Smith to reach this state of serenity. He doesn’t want to sound completely rehabilitated, either. Smith drifted from family. From himself. Only recently, about two years before this chat, did Smith sincerely take his demons head-on. Precisely what drove Smith to such amazing heights in the NFL — his mind — became weaponized against him. More than any other sport, football can define a man. And who Jackie Smith was, to his core, was a man obsessed with outworking everyone.

What happens when you bleed and sweat and bleed a little more for 214 games, then your world comes crashing down in Game No. 215?

Somehow, you must find yourself again.

His rise begins with a tale American as apple pie: a high school crush. At Kentwood High, there were only thirty kids in his class, but one of his pals had a cousin in Baton Rouge who’d visit every so often and, by golly, the tenth grader was smitten. Aware that this girl’s father was Al Moreau, a record-setting high hurdler in the 1930s, Jackie Smith reckoned he’d join the track team to impress her.

He didn’t know the first thing about clearing a hurdle and the school didn’t even have its own functioning track. They’d count one lap around the football field as a quarter mile. Even worse, a leaky water tank would form a huge mudhole near the fourth light pole on this makeshift track — there was no way around it. Training in such slop might sound miserable, but in truth it actually helped the Kentwood track team. Once they competed on an actual track for their meets against other schools, about thirty- four miles south in Hammond, Louisiana, they could fly. “It was like running uphill,” Smith says, “and, all of a sudden, it leveled out.” The crush didn’t last, but his pure love for running sure did. He’d eventually fall for a girl with a white Corvette named Gerri from a town five miles north, too.

Smith won states in the hurdles with one flat-out refusal to lose.

“I was determined,” he says. “It’s a game of arms and legs played mostly from the neck up. Once you have the ability to do something, it’s about how you think about it and how you position it in your mind.”

He played football, too, as a way to stay in shape for track. Five total games, anyways. After riding the pine as a junior — only punting occasionally — Smith got his shot as a “spinner back” in Kentwood’s single wing offense his senior year. Translation: He’d catch the direct snap and usually hand the ball off to somebody else. Then he broke his shoulder in the fifth game. After getting shoved out of bounds, Smith started to lift himself up, and another defender leapt on top of him. That following week, Mom drove him to New Orleans to see a specialist. Smith’s shoulder was so damaged that for six weeks he needed to wear a body cast that wrapped around his entire body and rested on his hips. Sleeping was impossible many nights. His cracked shoulder never did fully heal, either.

No, Smith did not resemble a Ditka-like predator. The track was his home.

Little did Smith know that thinking on his feet at the state track meet would trigger an NFL career.

The meet was held in Natchitoches, Louisiana, at Northwestern State University, the same school that had already offered Smith a partial scholarship. Which was nice. Unfortunately, his family didn’t have the money to split the difference. Dad was a good man, a quiet man, who eventually worked hard enough as a welder to open up his own shop thirty miles from Kentwood, but Smith knew his only realistic shot at attending college was a full ride. After taking first in the hurdles, he was greeted by Northwestern State’s track coach, Walter Ledet, near the finish line. The two went for a short walk, with Ledet reiterating how much he’d love for Smith to join his squad. Smith saw an opening. He informed Ledet that Southeastern Louisiana in Hammond had contacted him, too. It wasn’t a lie. Southeastern did call him and South-eastern was much closer to home, too. The statement was simply marinated with a microscopic drip of embellishment and a pinch of urgency.

The maneuver worked. Soon after, Ledet called Smith to say the university could grant him a full scholarship under one condition. He also needed to play for the school’s football team and could not quit.

He didn’t think twice and, to this day, the counterfactual still confounds him. He’s still not sure where his life would’ve floated without this offer.

Of course, the last time Smith had played football, he ended up in a hospital bed. For whatever reason, Smith wasn’t afraid one bit. “I would just move it along.” In college, he served as the team’s punter and caught a pass once every blue moon. In 1960, Smith had 10 catches for 129 yards. In 1961, he had 9 for 95. The school doesn’t even know how many passes he caught in ’62, only that the team’s leader had 13. The Demons, indeed, were a run-first operation. Playing in the NFL wasn’t a speck of a dream in his mind. Little did Smith know that St. Louis Cardinals trainer Jack Rockwell stopped by campus one spring. Rock-well watched the spring game and, Smith thinks, saw him sprinting around the track, too. The 1963 NFL draft arrived and, as the seconds ticked down at number 129 overall in the tenth round, the Cardinals couldn’t decide who to take. That’s when one person in the room blurted out, “Ah, hell, just take that redheaded kid from Louisiana.”

Smith got the call. Smith couldn’t believe it. He thought St. Louis made a mistake. Once he realized this was real life, one thought crossed his mind: “If they’re crazy enough to draft me, I’m crazy enough to make this damn team.”

The only person Smith knew with any pro football ties just so happened to be one of the best flankers in the sport. Charlie Hennigan was tearing up the new American Football League and had a background similar to Smith. After originally attending Louisiana State University on a track scholarship, Hennigan transferred to Northwestern State and wasn’t thinking of pro football as much of a career, either. He went undrafted in 1960 and became a high school biology teacher. The Houston Oilers got around to signing Hennigan and he was an instant sensation. In 1961, he caught 82 passes for 1,746 yards (21.3 yards average) with 12 touchdowns. Thus, Smith had a hunch Hennigan — “a running machine, a godsend” — could supply a few pointers. With his newlywed wife, he headed to tiny Arcadia, Louisiana, to work out with him. This was where forty or so kids attended Hennigan’s football camp at an old schoolhouse and Smith convinced him to carve out some one-on-one time on the field.

There were no hotels out in the boondocks, so Smith knocked on the door of a woman who lived across the street and begged her to let him and Gerri sleep on a bed inside her screened-in back porch. For two weeks, Hennigan then supplied Smith the cheat codes needed to dominate pro football. Defensive schemes were elementary through the ’60s. Almost all teams ran man to man, so Hennigan meticulously broke down the footwork it took to leave a defender in the dust.

No doubt about it. These two weeks are the number one reason Smith even made the Cardinals team as a rookie.

Here, at Syberg’s, he jolts off his chair to demonstrate. Right away, Smith learned to never curve his routes. To, instead, explode — “Boom! Boom!” he says — out every single cut. The best way to do this was by throwing his legs and arms one direction at the same time. Inside this packed restaurant of patrons in their twenties, thirties, forties, this eighty-two-year-old pumps his arms like he’s back at Busch Memorial Stadium. “You have to be able to stop,” he explains, “and then give everything you can going the direction you want to go.” So engrossed in reliving the origins of his football career, Smith still hasn’t touched his beer. Part of me thinks he might even knock the glass over reliving this breakthrough.

Two middle-aged men who work at a bank in St. Louis spot Smith from across the room and visit for a few minutes. When they hear Smith is chatting for a book on the tight end position, they bust his balls.

“You’ll get some good information,” one jokes, “once you get through all the bullshit.”

“Believe it or not,” says Smith, “they’re friends of mine.”

He laughs and picks up where he left off. The Cardinals decided to plug Smith in at tight end, where his set of skills was foreign to a burgeoning position. Whereas Ditka and Mackey were more apt to catch a short pass and steamroll a defender, Smith used his speed. He burnt that same defender down the field. In Week 5 of that 1963 season, Smith put the Cardinals on his back in a 24-23 win over the Pittsburgh Steelers with 212 yards and 2 scores on 9 receptions. Year to year, his role steadily expanded from 445 yards as a rookie . . . to 657 in Year 2 . . . to 648 in Year 3 . . . to 810 in Year 4 . . . to a record- setting Year 5. That season, Smith caught 56 passes for 1,205 yards (21.5 yards average) with 9 touchdowns. Only two players in the entire league had more receiving yards. With most defenses trained to expect the tight end to run five yards and turn around for the ball, Smith would often sprint directly at the safety twenty yards downfield and turn in to the post or out to the flag. The Cardinals threw deep. Often. “A bad habit, I guess,” jokes Smith.

Central to his success was a work ethic. No X’s and O’s, rather an old-fashioned motor. As a 205-pound rookie, Smith told himself he’d either need to pack on muscle or carry a gun on the field. Each off-season, he traveled to Baton Rouge to train with Alvin Roy, a man ahead of his time who helped Smith put on fifteen pounds without sacrificing his torrid speed. Roy became pro football’s first full-fledged strength and conditioning coach in 1963, helping the San Diego Chargers win an AFL Championship, before winning Super Bowl titles with the Kansas City Chiefs (1970) and Dallas Cowboys (1976). He’s now in the Strength and Conditioning Hall of Fame for sculpting human beings like this. The chiseled, 225-pound Smith maintained 4.5 speed in making five straight Pro Bowls from ’66 to ’70. Remarkably, his career average of 16.5 yards per reception remains a tight end record and is more than a full five yards better than the position’s all-time receiving leader, Tony Gonzalez.

One day, Smith was hanging out with two of his best pals on the team — offensive tackle Dan Dierdorf and linebacker Tim Kearney — when Dierdorf asked Smith if he ever got tired on a football field. Kearney immediately began to laugh. “Of course he did!” he said. Unfazed, Dierdorf told him to let Smith answer the frickin’ question. Smith kept thinking, and thinking, and, no, he couldn’t remember one instance. He was dead serious. After working out all off- season long before one season in the late ’70s, Kearney wanted to test his endurance against Smith. He was ten years younger than the aging tight end and figured he could take him. Without warning, he asked Smith to go for a run. Smith grabbed his shoes. And mile to mile, as Kearney breathed heavily like a dying fish, unable to talk, he couldn’t believe how Smith tried to carry normal conversations in a normal voice. After five miles, Smith asked if he wanted to kick this run “in the ass.” Kearney declined.

“I said, ‘I’m good,’” Kearney recalls. “I put my hands on my knees and go, ‘Jesus, Mary, and Joseph. Look at this guy. Ten years older than me and he’s running me into the ground.’”

That was Jackie Smith’s secret. Late in games, when most everyone else got tired, his speed would not wane. Dallas Cowboys safety Cliff Harris, a six-time Pro Bowler, believes Smith was the first wide receiver type playing tight end.

“Oh my gosh, he was fast,” he says. “He was big and tall and lean and muscular and fast.”

In real time, Smith had zero clue he was defining a position. He never imagined what a tight end would resemble twenty years down the road. He was grateful, only grateful, repeating his favorite line here: “Can you imagine how lucky I was?” A day prior to this lunch, Smith filmed a TV commercial where the director asked if he’d refer to himself as a Hall of Famer. He couldn’t do it. Felt too awkward, too conceited, too . . . not him. He always lived by an old saying: “When you’re green you’re growing and when you’re ripe, you’re dead.” He never wanted to think he had arrived.

Most remarkable was that all factors seemed to be working against Smith in St. Louis.

The team mostly stunk. Even when they started winning with new head coach Don Coryell, in 1973, one of the game’s greatest innovators ever wasn’t yet experimenting with the tight end. Smith stayed in a three- point stance next to the tackle. The most he ever split out was three yards, and it wasn’t even to run routes. If Smith strayed off the line it was because he needed to block a linebacker on a sweep play. Thinking back, damn, he wishes he was able to split five, ten, fifteen yards outside to test this speed against linebackers in open acreage. Unfortunately, nobody was doing that through the ’70s. Back then, Kearney would clothesline opposing tight ends. He cannot imagine what Smith would’ve done if he didn’t have to deal with a linebacker. “They would’ve had to outlaw him,” he says.

In practice, linebacker Bill Koman hit Smith so many times that Smith started to think it was normal to look out of his earhole. He learned quickly that if he could avoid Koman’s kill shot, he could toast any linebacker downfield. As a result, few even had a chance to clothes-line him. God help them if they did. Dynamite pass- catching ability never came at the expense of renegade toughness. Judging by his name and take-no-prisoners game, running back Terry Metcalf jokes that he always thought Smith was African American before they became teammates. His best memories are Smith accidentally tackling him (“He was coming down to help and, ‘Pow!’”) and the time Smith ran through what felt like the entire Cowboys defense for a TD. This locker room was full of the most hostile players in the sport, mind you. In 1977 alone, right guard Conrad Dobler was named “Pro Football’s Dirtiest Player” by Sports Illustrated, and left guard Bob Young competed in the World’s Strongest Man Competition.

But the one player everyone knew to never mess with, Kearney says, was Jackie Smith.

Especially opponents.

Once, a defensive back for the Washington Redskins punched Metcalf and . . . Smith snapped. He didn’t give a damn that he was in street clothes, on the bench, out with an injury. Smith immediately ran onto the field to attack the perpetrator. Officials ordered Smith to get the hell off the field, thinking this was some crazed fan. Once they realized it was perennial Pro Bowler Jackie Smith, they made Smith sit in a special seat up against the stands far, far away from the bench. Thinking back, Metcalf chuckles. Cheap shots always did “raise the hair on his neck.” Smith was the team’s protector. In the midst of this particular melee, Smith made a mental note of that Redskin player’s number to one day get his sweet revenge. One year later, he thought the moment had arrived. He visited his mother in Jackson, Mississippi, and couldn’t believe it when she said a Redskin player had just moved in one block away.

“Really?” said Smith, tensing up. “Did he tell you what number he is?”

He hadn’t. But Mom did say the player wanted to see Smith.

His jaw nearly hit the floor. Right then, Smith told himself that Jesus Christ himself must’ve delivered him this opportunity at vengeance. “Divine providence!” he thought. “I can get my shot in.” Smith walked right to the player’s front door with a clenched fist behind his back. He knocked, the player opened, the player was extremely friendly.

“Hi, Jackie!”

Smith ignored him. His blood was boiling. “What’s your number?” he asked.

The player told him. It was somebody else. Smith unclenched that fist.

“Nice to meet you!” he said warmly, extending a handshake. The two had themselves a fantastic visit, and Smith returned to his mom.

Then there was Harris, the Cowboys safety. One game, he tried tugging and pulling Smith’s jersey to get inside his head. Nothing abnormal. Nothing he hadn’t tried with any other player. But, no, Smith was not having this. Irate, he looked Harris squarely in the eyes and said to meet him in the parking lot after the game. He was not bluffing.

No wonder he loved challenging the most cannibalistic linebackers of his era. He’d get his bell rung by Green Bay’s Ray Nitschke and Chicago’s Dick Butkus and return for seconds. His primary foil was Butkus, a man who never referred to Smith by name — only “punk.” One game, Smith had enough of his shit and got a good shot in, but unfortunately, Butkus had the last word. He kicked Smith, crushed his facemask in, sent him to the sideline. Like Ditka, this tight end bonded with his enemies off the field, too. When Smith visited the Packers Hall of Fame in Green Bay, Wisconsin, he remembers Nitschke grabbing one of his sons and plopping him right on his knee. It was a different time.

“Back then, they didn’t care what happened,” Smith says. “They just asked me, ‘Do you know where we’re playing?’ And, ‘How many fingers do I have up?’ And that’s it. ‘Go back in. You’re good to go!’ It’s not that I could block ’em or hit ’em or hurt him or anything. But going against people like that? What an honor.”

The beatings added up. Against one team — he cannot remember who — Smith caught a pass and didn’t wake up until he was on the bus heading to the airport. It was horrifying. He had no recollection of getting dressed or walking onto the bus. Only his momentum carrying him out of bounds and everything going black. He did the math and figured he was out cold for an hour and a half. “What the hell?” thought Smith when he came to. He reenacts the scene here with wide eyes darting to his left and right. “I didn’t want to say anything. I sat there and said, ‘How did we get here?’” From what he was told, an opposing player who was already on the sideline hit him.

The field they shared with the Cardinals baseball team at Busch Stadium was terrible, too. Once, a torrential downpour before kickoff against the New York Giants rendered the infield swath of the football field a total mudpit. Players all resembled mud zombies. Running a ten-yard pattern felt like running the mile because the weight of the mud on Smith’s uniform was unbearable. Of course, this was paradise compared to the AstroTurf installed in 1970. The padding, if you could even call it that, laid underneath the turf was designed for a baseball team so the ball would bounce high off it. “That didn’t mean our ass bounced off it!” Smith kids. He started wearing cleats with steel tips to keep his footing even if that meant gouging an opponent’s flesh. Hey, it was survival of the fittest out there.

And after fifteen seasons, it was time. He retired.

The end of his Cardinals tenure was marred by a spinal injury that would make his arm go numb on contact. When he initially injured his neck, he couldn’t walk. Teammates helped him off the field. “Like it paralyzed me,” Smith says. “That was the first time anybody helped me off the field.” The final blow, in 1977, was when the arch in his foot was flattened. He still gets on running back Jim Otis’s ass for that one every time he sees him here in St. Louis. Otis — “the king of cutback,” as Smith called him— changed direction (yet again) and stepped right on his foot. Smith was done . . . or so he thought. Right before the ’78 season, Cardinals coach Bud Wilkinson asked the thirty- eight-year-old if he wanted to return. The tight end underwent a physical and — after a week of silence — called the team himself for the results. That’s when he claims the Cardinals told him he had failed the physical and that one more hit could leave him paralyzed. Part of Smith later wondered if Cardinals owner Bill Bidwell simply didn’t want him back. To this day, his relationship with the team is strained. He’s still emotional about it, too, banging the table with his fist as he relives painful memories. Smith is the team’s only Pro Football Hall of Famer whose name isn’t in its Ring of Honor.

The ’78 season began. Then, exactly as he did nine years prior, Tom Landry picked up the phone to call an aging tight end great. Thinking this was a prank, Smith first hung up.

When Landry called back, the Dallas Cowboys coach asked if Smith was in shape and convinced him to head south to see the Cowboys’ doctor. He coveted his leadership and knew that Smith — like Ditka — would bring something extra to his locker room. This was also a golden opportunity for Smith to pursue the one accolade that eluded him all those years in St. Louis: a Super Bowl ring. The Cowboys were the defending champs and had spent most of the decade serving as big brother to the Cardinals in the NFC East. Smith had played in all of two playoff games, catching one pass in each contest. Landry told Smith not to worry about his neck. So he didn’t. He headed south, met with a team doctor, and estimates the physical took all of fifteen minutes. In fact, it hardly felt like a physical at all. When Smith informed this doctor that the Cardinals’ doctor thought one hit could paralyze him, he waved it off.

Only later did Smith learn that this doctor was in a hurry because he was also a farmer and had to get a load of cattle off to an auction.

“So,” says Smith, chuckling, “he rushed me right through the whole deal.”

He’s glad. This was the most fulfilling season of his career.

The same players who had been trying to take him out for years embraced Smith with open arms.

That Monday, walking to the training room, Harris peered into the locker room and couldn’t believe his eyes. “Cliff!” yelled Smith, with a warm handshake. “I’m on your team now!”

“Oh, thank goodness,” Harris replied. “I thought you were here to whoop my ass.”

When Smith ran into Lee Roy Jordan, the longtime linebacker reached into his mouth and pulled out two partial dentures. “I always wanted to show these to you,” he told Smith. “They’re compliments of you.” Jordan had since retired. But apparently in a long-ago Cowboys- Cardinals bloodbath, a different linebacker (Jerry Tubbs) gave Smith a cheap shot, and Smith sought revenge. On a sweep play shortly after, instead of blocking the safety as assigned, Smith waited back for Tubbs. He saw a silver helmet, threw a forearm and, whoops, wrong guy. The blow knocked Jordan’s two front teeth out.

They laughed it off.

Smith fawns over the unflinching head coach in the fedora, just like Ditka. There were no pregame speeches sending players through the nearest wall. The motivation came in wanting to execute Landry’s brilliant game plans. They were so specific, so detailed, that nobody wanted to let him down. What impressed Smith most was Landry’s knack for identifying an individual player’s weaknesses and attacking. He’d explain to everyone why exactly the Cowboys were going to run ten specific plays, detailing how one set up the other. His demeanor was stoic, but his schemes? Cold-blooded.

“That’s what made him so extraordinary,” Smith says. “The players didn’t mess around. They wanted to make sure they didn’t miss anything or they didn’t upset him about anything. They didn’t actually say that, but you could tell by their actions.”

This was the same year the Cowboys earned their “America’s Team” nickname from the legendary narrator John Facenda. Even though he caught exactly zero passes in twelve regular-season games, Smith’s value to this 12-4 team was undeniable. Harris could tell this was a player willing to do anything for a championship. He could still run a 4.6 but his role, now, was to block. And lead. And stand up for his guys. One night in the middle of the season, Charlie Waters had a party at his house, and Harris couldn’t believe that one person at the party was flirting with his girlfriend. It wasn’t a player. Smith had no clue who this was, either, and it did not matter. He beelined in that direction, grabbed ahold of this joker by the collar, and held him straight into the sky. “Hey! Don’t you mess with Cliff Harris’s girl!”

In the playoffs, against the Atlanta Falcons, Smith had arguably the best catch of the day. His two- yard touchdown reception tied the game up, 20-20, in the fourth quarter and was anything but easy. In for a concussed Roger Staubach, back-up Danny White rolled right and flicked it to Smith, who deftly boxed out a defender along the goal line and tapped his toes down before absorbing a hard hit to the midsection. The Cowboys won, 27-20.

Sensing that this conversation is inching closer to his nightmare when I bring this touchdown up, Smith redirects to other topics. He praises Landry. He goes off on chicken wings of all things. After we order another round of beers, Smith asks the waitress if any of the Sybergs are around because they once tried to swipe his world-famous chicken wing recipe. Smith originally plucked the recipe from a teammate, Irv Goode, and used it at his own restaurant, Jackie’s Place. Now, Smith can always tell when any restaurant is half-assing wings. There’s a top-secret ingredient, he notes, that most cooks neglect.

“I still have the recipe,” he says. “Something was written where I was given credit for bringing the buffalo chicken wings to the Midwest. My name was in there! I said, ‘I’ve got it made now!’”

If only this was how everyone remembered him.

In the NFC Championship, the Cowboys pummeled the Los Angeles Rams, 28-0, to tee up a Super Bowl showdown with their dreaded rival, the Steelers.

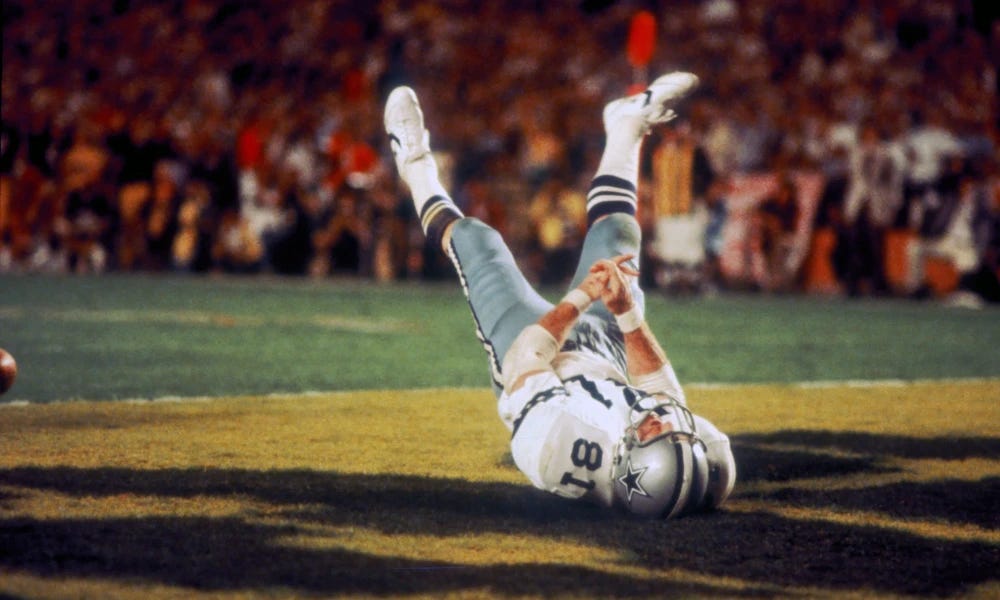

Smith is ready. He’ll discuss the drop now.

“I’ve never said this to anybody,” he begins. “I’ve never talked about it.”

So many of Jackie Smith’s closest friends — Kearney and Harris, included — have never dared to bring this play up to their pal. They know how much it has haunted him. In truth, the devastation at the Orange Bowl in real-time spoke for itself. The reactions of all parties involved may be the reason why a play that occurred with two minutes and forty-six seconds remaining in the third quarter, not even the fourth, still resonates today.

On the Cowboys’ radio broadcast, play-by-play man Verne Lundquist famously stated, “Bless his heart! He’s got to be the sickest man in America!” On the NBC national broadcast, Curt Gowdy shouted, “He dropped it! Drop! Jackie Smith! He’s a great human-interest story: Fifteen years with the Cardinals, it’s the first time he ever had a chance to go to the Super Bowl. And he let a sure touchdown pass get away.” On the field, it was worse. The ever- emotionless Landry threw his hands up in dismay. Quarterback Roger Staubach threw his head back in disbelief. And, of course, there was Smith. He clenched his fists and kicked his legs into the air.

This was how everyone at home consumed the play. In reality, the details that went into this moment and game have been mostly ignored over time.

Start with the play call. On third-and-three from the Steelers’ 10-yard line — with the Cowboys trailing 21-14 — Landry sent “47 QB Pass Y Corner” into Staubach. The quarterback called timeout because this didn’t make sense. This was a goal- line play, one Dallas had implemented all but one week before. Why would Dallas call it at all, in the Super Bowl, let alone from the 10? Not once did the Cowboys practice “47 QB Pass Y Corner” this far from the goal line. Landry instructed his quarterback to run the play anyway. The design sent two receivers to the pylons. Running back Tony Dorsett motioned left to right before the snap and dripped into the flat. And Smith? He was the fourth option, instructed to go to the back of the end zone and wait. Staubach later told Sports Illustrated that the Cowboys should’ve never called the play. “We can blame what happened,” he said, “on Coach Landry.”

Nonetheless, the play did scheme a player wide open.

After Staubach faked a handoff to running back Scott Laidlaw, linebacker Jack Lambert stormed in on a blitz and Laidlaw stoned him. That gave Staubach ample time to locate Smith in the end zone.

With those tenders polished off, Smith begins by explaining that he needed to block his man off the line a second longer to sell the run fake. This was a goal-line play call, after all. Smith released, stripped through the line, and never saw Staubach release the ball. For fifteen years, that was something he always looked for on plays like this. If he could’ve seen how the football was leaving the quarterback’s hand, Smith knows he would’ve made the same adjustment as Staubach. The quarterback later told Smith that he was shocked to see him so wide open, so he tried softly floating it to him. He took a few RPMs off this pass.

Once Smith realized this? It was too late. He hit the brakes, slipped, and dropped the ball.

“He told me later, ‘You were so damn wide open, I wanted to make sure I got the ball to you,’” Smith says. “So, it wasn’t like a regular pass he’d throw to me. He didn’t throw the ball as hard. In other words, if there was somebody (covering) me, he would’ve zipped it in there to get through. But I was so wide open. That being the case, I had to stop, and it was behind me because it was a little bit lofty. When I had to put the foot down to get back to get it, I didn’t get back far enough.

“It’s as simple as that.”

Everlasting, too. It didn’t matter that Staubach threw an interception at the end of the first half, with Dallas driving, and the Steelers quickly drove to score a touchdown of their own. Nor did it matter that Randy White fumbled a kickoff return in the fourth quarter or that the NFL’s No. 2-ranked defense allowed Pittsburgh’s Terry Bradshaw to throw for 318 yards and 4 touchdowns on only 17 completions. Nor did it matter that both Harris and White lament their own gaffes to each other still to this day and that Harris tried telling Smith the entire team lost that night in Miami. In the locker room afterward, Smith answered questions from reporters for forty- five minutes. “I hope it won’t haunt me,” he said then, “but it probably will.” He was proven correct.

Here, his words slow to a crawl. Asked how he coped with the drop over the following days, weeks, months, a man who could literally talk all day clams up. He forces a slight chuckle.

“They were different. For a while. It was, it was . . .”

Another long pause.

“. . . different.”

That night at the Orange Bowl should’ve been the crowning achievement he deserved. Instead, here is what “different” entailed. Strangers called the family’s house to inform Smith he blew the game. One angry caller who phoned the Häagen-Dazs store Smith opened in St. Louis was especially malicious. This person, Sports Illustrated explained, told Smith the drop cost him $20,000. All four of his kids were ridiculed at their high school and college sporting events. His daughter, Angie, was walking back to her car after one race in track when someone mocked her about the dropped pass. She proceeded to beat the hell out of the kid.

Catch that pass and he’s a conquering hero. Instead, this became everyday life. A game he grew to love suddenly was bringing him nothing but an avalanche of negativity. The best way to cope—the only way— was to remember the good football provided his entire family. When he fielded all those questions in the losing locker room, fourteen- year- old son Darrell was at his side. Dad clung dearly to the fact that playing in the NFL for sixteen seasons afforded his kids so many opportunities.

An optimistic man to his core, he is beyond proud of them all.

He chokes up thinking about the lives that Sheri has saved as the principal at Danforth Elementary, a school full of kids from impoverished backgrounds that desperately need guidance. She possesses the innate ability to either “kick them in the ass or love ’em,” he says. “The kids love her. They go from one classroom to the other. They’ll get out of line, run in, give her a hug, then run back out. She’s touched them all because of the way she is.” Both his sons, Greg and Darrell, are in sales. Darrell went to Arkansas and Greg to Dartmouth, and he cannot stop thinking about the trip he has planned with Darrell this month to head back to Louisiana. They’re going for Jackie’s birthday, and you better believe they’re ready to hit up all the Cajun music and food joints possible.

His other daughter, Angie, was a phenomenal athlete just like him. Tall, strong, with a stride to leave all in the dust. Now retired, she’s excited about a property she purchased way out in the country.

Altogether, Smith now has fourteen beautiful grandkids, too.

“Playing a football game, for God’s sake,” he says, voice raised. “Look at what it’s given us!”

All the blowback was worth it. He can live with how people treated him because, hey, he could’ve been hauling pulpwood for a living.

“I have nothing — nothing — to complain about,” he says. “No regrets at all . . . I knew how important it was for our family. It’s paid off. And they’re doing well because we did this. I don’t give a shit about anything else, when it comes to how it affected me. That’s the biggest blessing. That being the case, it was worth that. If I had to go through that deal to have the family life we do and for those kids to be as successful as they are, and people like to see me and talk about football? I feel so lucky.”

Physically, he’s no doubt in the top percentile of players from his era. That shoulder he injured back in high school finally quit on him about twelve years ago, and Smith needed it replaced. Soon after, he jokes, the other shoulder got jealous. He needed to replace that one, too. Otherwise, he’s felt phenomenal. Getting into the Pro Football Hall of Fame sixteen years after retiring was validating. The first phone call he received when the news broke was from Mackey, a gesture he still treasures. He’s wearing his enormous Hall ring today. Nobody can ever take this away from him even if no player’s legacy in this hallowed ground has been so drastically warped.

Yet, the scars from that night never healed.

A passion that filled Smith up with so much joy was now hammering him with despair and he became distant. He refused to address the man in the mirror directly and never wrote a book or spilled his guts on national TV as a form of a catharsis. There’s still no relationship with the Cardinals, either. He believes it all stems from an interview he did with the Dallas media upon signing, when he simply explained what transpired. Worst of all? He never opened up to family like he should have. He allowed the drop to hijack the relationships with the same people he loves so dearly. An Emerson quote may keep him on track today, but for too long Smith admits he was “wandering around” mentally. He felt sorry for himself and flat-out ignored what’s most meaningful in life. It wasn’t until 2020, into his eighties, that Smith looked deep within and told himself, “You’re one stupid son of a bitch.”

“I was making excuses because of the Super Bowl and all that bullshit. Maybe I was trying to find something to help me forget about stuff that was going on in my mind. Because what happens is you condition yourself for that, to do what you need to get done. And when you do that, you take away from a lot of other things. And a lot of those other things are your family. Quite frankly, they’re not going to be able to understand. They just can’t imagine that a mind can be so . . . almost . . . a different mind. They can’t imagine how that can change. You have to pay the price for things you didn’t do. The ways you didn’t think. The affection you didn’t show.

“You’re trying to look at other things and trying to say other things are important. ‘This is the way I should think about it.’ And while you were doing that, you’re ignoring your family.”

A tear rolls down his cheek. With one deep breath, it’s as if Jackie Smith is releasing a burden.

“I know what I did and what I didn’t do.”

Seconds later, his phone rings. Check that. His ringtone is actually a hilarious duck quacking at full blast.

It’s Angie calling for the third time today. Something as simple as seeing her name appear on his phone is what Smith lives for now. The phone quacks again and he’s stunned to see the name on the screen. It’s a friend Smith actually thought was dead. He answers. “It can’t be. It could be. It is!” he says to the caller, overwhelmed with joy. “What are you doing, nutcase?” Smith jokes that he’s sitting down with some-one for a book, telling lies about how good a guy he is and that he could use some help. “Get your ass on over here!” He laughs and the two agree to meet up at two o’clock the next day. “Love you,” says Smith, before hanging up.

Phone calls like these mean the world now. Especially with so many loved ones passing away.

Koman, the linebacker who hardened him, died in 2019. Former Cardinals quarterback Tim Van Galder died of cancer just a few weeks before this chat. Through Mackey’s “88 Plan,” Smith has been helping Van Galder’s family transition. As so many teammates and opponents die, here’s one of that generation’s best tight ends just now experiencing an awakening. Whereas a phone call from Tom Landry boomeranged Mike Ditka into football immortality, Smith spiraled into a darkness that took decades to escape.

Finally, he’s genuinely happy. Relationships with loved ones are closer than ever.

Kearney knows he can call Smith any day, anytime, to grab some beers. (“As good of a football player as he is, he’s an even better friend. He’ll do anything for you.”) Metcalf lives in Seattle now, but it meant so much to see his old protector at his induction into the St. Louis Sports Hall of Fame. (“He was a humble man. When he put the uniform on, that humbleness became very, very aggressive in trying to accomplish what he needed to. He had a big heart. Jackie loved people.”) Harris lives in Dallas but has made a point to visit his old friend in St. Louis. In Smith’s office, he spotted the image that everyone should think of when they hear Jackie Smith. Blown up as a poster, it’s a completely horizontal Harris, getting spun around, trying to tackle Smith downfield. That’s who Smith really was, he says. The two still talk regularly.

Nothing will ever again detract from family. The older Jackie Smith gets, the more this reality dawns on him. He stays busy, but never too busy. For years, Smith ran his restaurant, sold fishing shows, sang the national anthem at sporting events. Now his labor of love is building a Vietnam War memorial eighty miles south of St. Louis in Perryville. Now, whenever his plate gets too full, he pulls something off it. He reprioritizes. As for his legacy? How he wants everyone to perceive him as a player? He hopes folks remember him as a nice guy. That’s about it. He’s not concerned about what others think because he reclaimed his identity on his terms. Smith doesn’t even like the suggestion that he “persevered” because that insinuates that he was doing something he didn’t enjoy. And he sure enjoyed being an NFL tight end. At the heart of the position, he loved the idea of answering to one person: himself. That was how this whole wild journey began in Kentwood and why he worked so hard to make the team with Hennigan and trained harder than anyone else every off-season.

“To keep fooling their ass,” he kids. “Nobody liked to work out with me because I liked to work.”

It was never the drop that made him emotional. The drop, given all those variables, he can live with. What makes him emotional is how he allowed that play to steer him away from the people he loved. He needed to rediscover the person he’s been all along. That’s a man who’ll reach out to one of his children just because and a man who’s still working out like he’s trying to make an NFL team. Perhaps the best proof that Smith is a man at peace can be found in a gym where he still throws dumbbells around and climbs a StairMaster with a purpose because he never wants to just “look pretty” on a machine. What good is that? If he’s going to sweat, he must sweat. He’s still leaving friends in the dust on runs, all at the ripe age of eighty-two.

It’s psychological more than physical. Working out forces Smith to once again answer to himself. He views each run, each lift, as a way to pay a price for all the blessings that have come his way.

“I have to feel like I deserve what I’m getting,” Smith says. “I’ve got to be content with myself.”

OK, so he’s not knocking teeth out. He is finding that edge within all over again.

“I would’ve hated if I would’ve had the opportunity to play and do something for the family, like that, and then I didn’t make it. If I would’ve gone through the process of trying to make the team and slacked off a little bit or took shortcuts or done things I shouldn’t be doing. I didn’t want to be released from the opportunity and say, ‘If I would’ve had a different way of looking at it’ and ‘If I would’ve tried a little bit harder.’ To me, that’s why people kill themselves.”

His legacy can be found within the very soul of the sport and has nothing to do with those 5.5 seconds. So many tight ends who followed Smith have emerged from the strangest locales. Cornfields in Iowa. Group homes in North Carolina. The roofs of houses in sweltering summer heat and, why not, a bar fight or two. Smith was the first to truly prove that relentless tenacity can overcome all circumstances. That’s the lifeblood of this position. So, heck yeah, he wakes up with a smile every single morning. He asks to see pictures of my two kids and lights up at the shot of a two-year-old Ella posing. “She’s sassy!” he says cheerfully. With that, Smith starts tapping away on his phone to show off pictures of his family. Initially, he’s seeking one specific shot until, for a good ten minutes straight, he cannot stop scrolling and scrolling and sheds a tear for all the right reasons.

Moments later, he doesn’t want to hear about any visitor of his traveling via Lyft or Uber. He invites me into his trusty black Pilot — the “sled,” he calls it — and takes off. There’s more than 246,000 miles on this vehicle and he fully intends to run it into the ground. As we drive around St. Louis, Smith explains how difficult it was for this city to lose its football team a few years back. Fans were quite emotional.

He pauses. He appears to be thinking about everything that happened in his life after January 21, 1979, once more, but this time he lets the words hang in the air.

Big plans are set for Wednesday. He’ll see that long-lost buddy, stop by his daughter’s school to say hello, and, of course, make sure he’s cherishing every second.

“The Blood and Guts: How Tight Ends Save Football” is out now. Buy your copy today at Amazon and everywhere books are sold.

©2022 Tyler Dunne and reprinted by permission from Twelve Books/Hachette Book Group.