The art of play sequencing -- and how Sean Payton rediscovered his mojo

The Broncos broke with tendencies to set the Packers up and drill them over the head

There are so many explosive, layered story lines to this NFL season: Drake Maye’s growth; Ben Johnson’s transformation of the Bears; the end of the Chiefs’ dynasty; Philip Rivers’ return; Mike Tomlin staving off the executioner for another year; and so much more.

But don’t overlook the most impactful, habit-altering development of the late season: Sean Payton has rediscovered his fastball.

The Broncos are 12-2, sitting as the No.1 seed in the AFC. They have one of the two-best defenses in football, and comfortably the most adaptable. But over time, Payton’s offense has slowly risen to match the playoff standard. For much of the year, the Broncos’ offense has been rickety. But since Week 8, Denver ranks 8th in offensive EPA/Play, 9th in rushing success rate, and 7th in dropback EPA/Play, despite the explosive plays drying up. For all the (fair) doubts about Bo Nix and the team’s lack of blue-chip talent, that’s a solid enough postseason formula.

The secret sauce to Payton’s success has long been his dedication to his protection plan. Keep the pocket solid, the idea goes, and everything else will slot into place. For all the talk about his bomb’s away passing attacks in New Orleans, it’s Payton’s commitment to keeping a solid pocket that has allowed his offense to sing for two decades.

Few are as detailed in their protections week-to-week as the Broncos coach, adding in fresh wrinkles to offset the tendencies of a defense. All coaches have a core cache of protections against specific fronts, defensive looks, or individual personnel. Where Payton separates himself is the sheer volume of specific protections he installs and his willingness to wholesale shift how he addresses defensive looks gameplan-to-gameplan. Some coaches will (understandably) bank on their base protections to carry them through (the Shanahan tree). It allows the players to rep the same looks over and over again to master what they’re doing. It also gives both the play-caller and quarterback the knowledge of where the weak points are in a certain protection against certain looks, with built-in answers to offset those weaknesses. Payton, though, jolts in the opposite direction. He wants every conceivable answer on the menu against every look.

In the most recent Payton playbook I have access to (his final season with the Saints), some 300-odd pages are dedicated solely to protections, roughly half the length of a typical NFL playbook.

Yet when you zoom out from the intricacies of the protection plan, you get to the base passing game. And for a guy who has roasted the league with some of its greatest ever passing attacks — the thing Payton is famous for — he is as doctrinaire as they come. Everyone has staples, but nobody rattles off the same stuff irrespective of the opponent more than Payton. Before any Broncos game, you can play Payton Bingo: write down the handful of concepts you know he wants to hit, and you can stamp them off before the middle of the second quarter.

Sure, Payton has evolved over time. In Denver, he has adapted his traditional ideas to suit Nix, embracing RPOs and shrinking the field by formation rather than expanding it. But the same cluster of concepts makes up the fabric of the passing game. Payton is not known for wholesale adjustments based on his opponent.

On Sunday, though, Payton broke with a lifetime of tendencies. It was probably his best individual gameplan since he rocked up in Denver — and it didn’t hurt that Nix had the performance of his life against a tasty Packers defense.

Payton broke his typical structure and layered play on top of play to punish the Packers. In doing so, he also showed the difference between being a game planner, play designer, situational play caller, and play sequencer. Being good at all four is tough. Being great is reserved only for the best. It’s why those roles are increasingly splintered between different members of the staff — and why some fail when they move from designer to the designated play-caller. But Payton put on a clinic against the Packers. Finally, it looked like his mojo was back.

(Sidebar: Every time I write or talk about Payton’s offense positively, it falls off a cliff. But what Payton put down on Sunday was too cool not to discuss. So, sorry in advance, Broncos fans.)

One of the most important building blocks for any modern offense is the idea of ‘layering’ one concept on top of another.

Layering is as it sounds: stacking one brick on top of another. It means adding fresh dimensions to an idea, a formation, a motion, a movement, a whatever, that builds on top of its base construct. Layering is often used as a synonym for pay-off plays. A coach carefully, artfully, builds in a tendency before breaking their own tendency for a big, explosive, chunk play. Jet-give. Jet-give. Jet-give. Jet-give. Reverse!

Lane Kiffin is the master at building towards payoff plays. But there are other, more subtle ways a coaching staff can layer their offense. For most coaches, adding layers is simply about not tipping what’s about come — breaking a tendency before it can truly gather steam, and a defense can get a read on what’s coming through formation or specific alignments.

At root, layering is about keeping the defense off balance. About asking linebackers to shuffle their feet, rather than triggering and firing one way or the other. About having the safeties creep down or shuffle back, not knowing if their eyes are lying to them one way or the other.

The best layer-ers (Matt LaFleur, Liam Coen) tie their run-game to their play-action game to their dropback attack — with RPOs built off those same structures. Tying the three together — having the action look, feel, sound like a run play — is what keeps the defense guessing or overplaying their hand in the worst possible moment.

Payton is not a typical layerer. He runs his stuff. He calls based on down, distance, and situation. But, good GOD, did he crush that notion on Sunday.

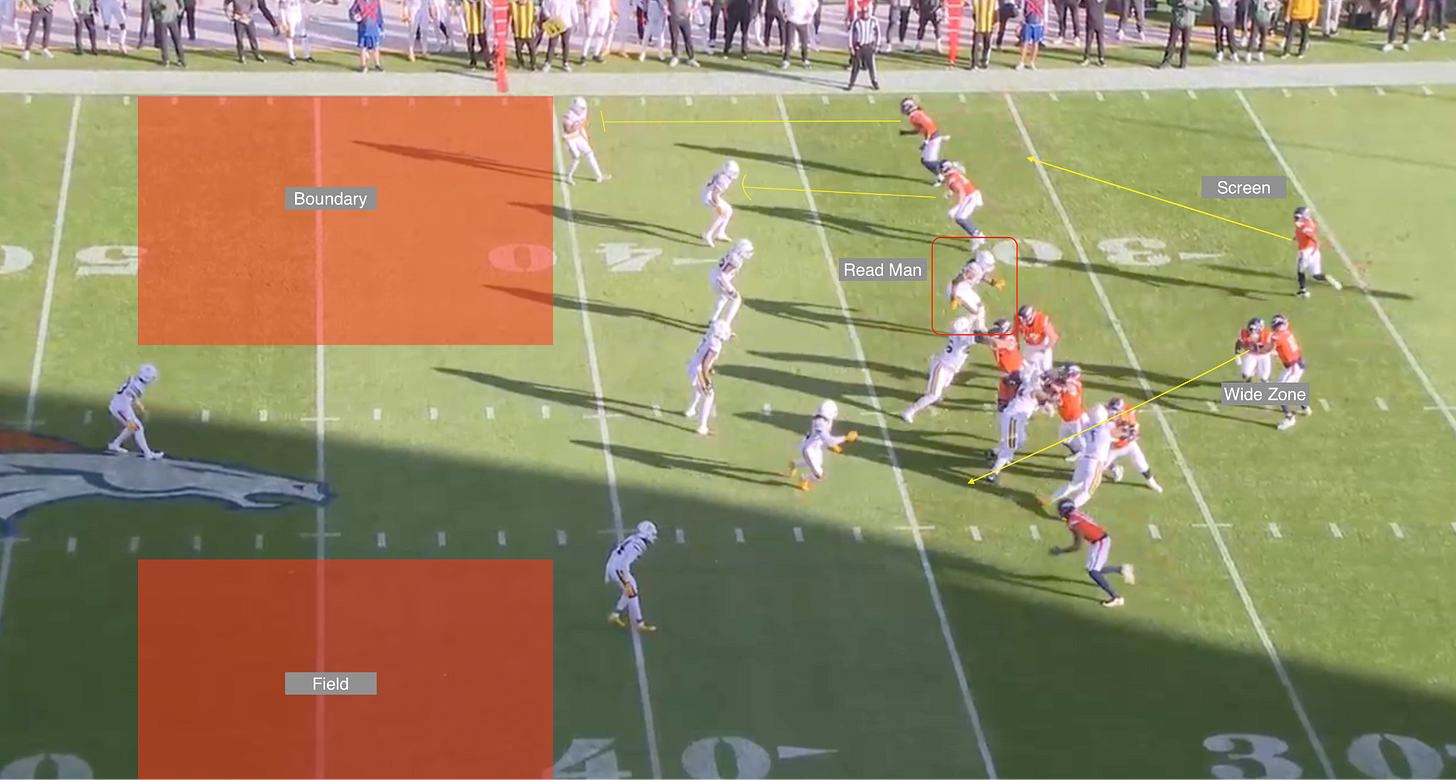

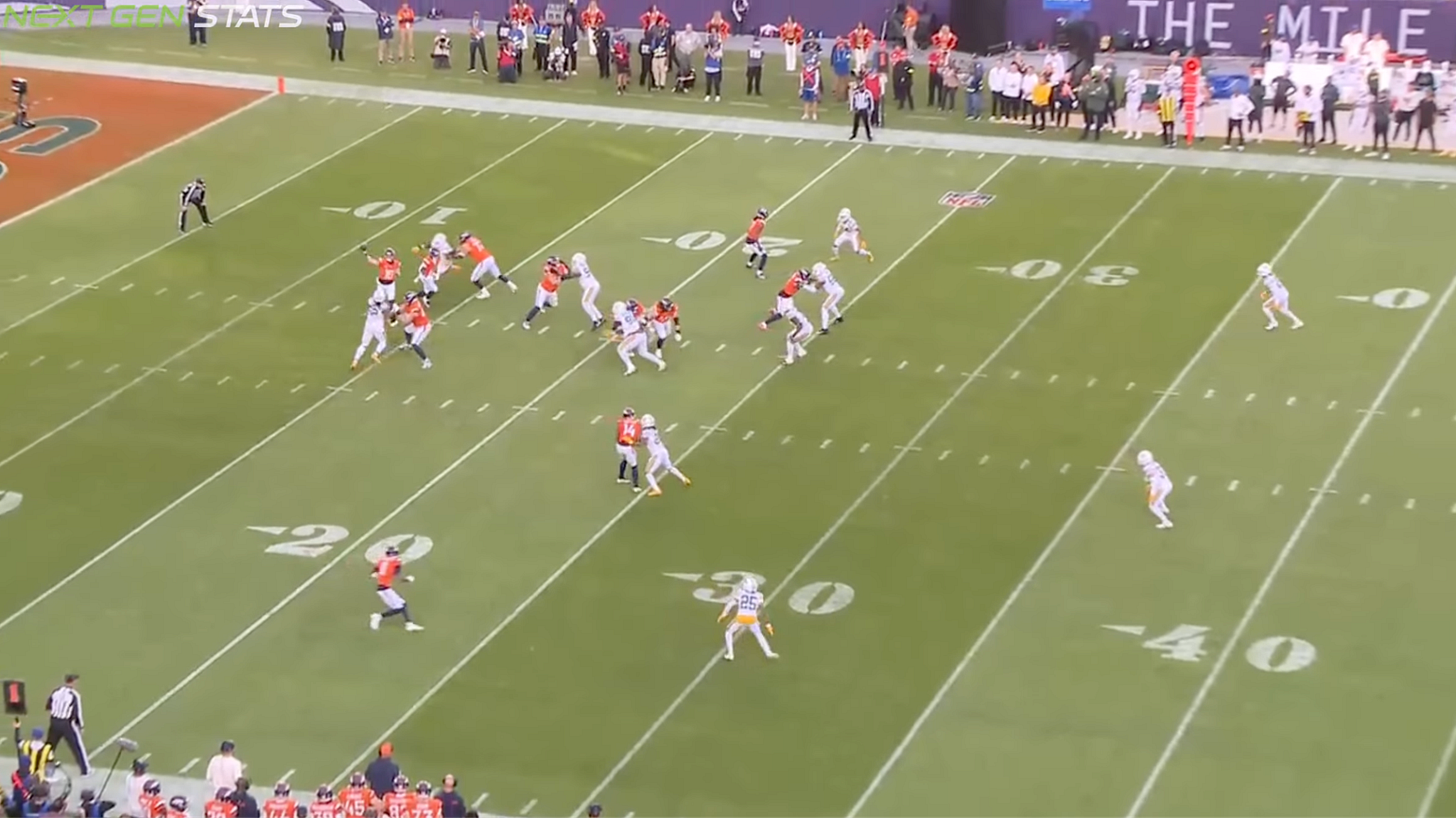

The Broncos built their attack by using formations into the boundary. When the ball is spotted on a hashmark, you have a field side (the wide side of the field) and a boundary side (the short side of the field). Below, the ball is spotted on the left hash, making the right side the field side and the left the boundary.

Planting the bulk of your eligibles into the short side of the field is knownas Formation Into The Boundary, or “FIB” in coaching parlance. It is not a staple in the NFL. The league average for FIB this year is just 6%. The Broncos run FIB at just a 4% clip. On Sunday, though, the Broncos ran with a formation into the boundary on 24% (!) of their plays, the fourth-largest volume of any offense in a single game this season.

Given the tightness of the hashmarks in the NFL compared to college, FIB is not a go-to. It’s usually the preservation of the spread-option world. It doesn’t help with a true, multi-progression passing game either, the bread and butter of the professional dropback world. With wider hashes in college, the space created by FIB adds extra strain to a defense. When an offense plants the bulk of their weapons into the short side and extends a player outside the numbers to the field at the college level, it’s a loooooot of grass to cover. In the NFL, it isn’t quite as hazardous — and the league doesn’t need to rely on anything that can be viewed as a gimmick.

And when Payton has dabbled with FIB in the past, it’s been to rip off the typical FIB concepts you will see at all levels: the quarterback run game, or varying screens. But on Sunday, Payton hit on something different. He used FIB to push and probe the Packers, to gather intel, and then set up chunk shots on crucial downs. He forced the Packers into specific looks so that he could rip them apart for touchdowns.

Layering starts with that first brick. Coaches approach their opening couple of drives or their game script differently. Payton is from the old school, those who adopt the approach of the Stasi. He runs out every array of personnel grouping, motion, shift, and formation to gather intelligence on the defense. Coaches spend those sleepless nights, missing those dance recitals, to find tendencies and tells from the defense. The opening script is used to confirm that information: Is the defense playing as we thought? What about against this look? How about this shift? Are they matching big personnel with big personnel? Are they adjusting how we anticipated? Are they trying something new because they know our tendencies? Have they switched things up based on their own personnel, our personnel, or because they’ve struggled with it in the past? You may have studied for the test, but the answers could change come gameday.

One thing that separates the best pay-off play-callers is their knowledge of the defensive rules. They spend hours breaking down a defense to understand how a defense wants to play against particular formations, route concepts, or pre-snap movement (a motion or shift). The best then take those rules and beat a defense with them. They will set up in one look, then move into another, forcing the defense to check into the specific coverage rules… and then the offense will have a coverage-beater dialled up to attack those very rules.

That early-game choreography is about checking whether your pre-game study of those defensive rules is accurate, or how the defense has decided to adjust. You plant something down, note it for later, then return to shatter the rules when needed most.

Let’s go back to Payton. His spread passing game is built around 3x1 or 3x2 sets. He plants three receivers to the field, using all the available grass to stress the defense. It’s also an isolation-based attack, with routes rarely intersecting. The idea is to uncover the coverage through formation and tendencies, giving Nix a clear picture of where he should go with the ball at the snap and drawing up predeterimed, one-on-one matchups against lesser corners – typically outside the numbers. And that’s precisely the weakspot for the Packers defense: cornerbacks Carrington Valentine and Keisan Nixon.

Put yourself in his shoes. Payton knows he has to find a way through formation and movement to isolate and attack those corners. He also needs to know the right time to pull those levers for maximum impact.

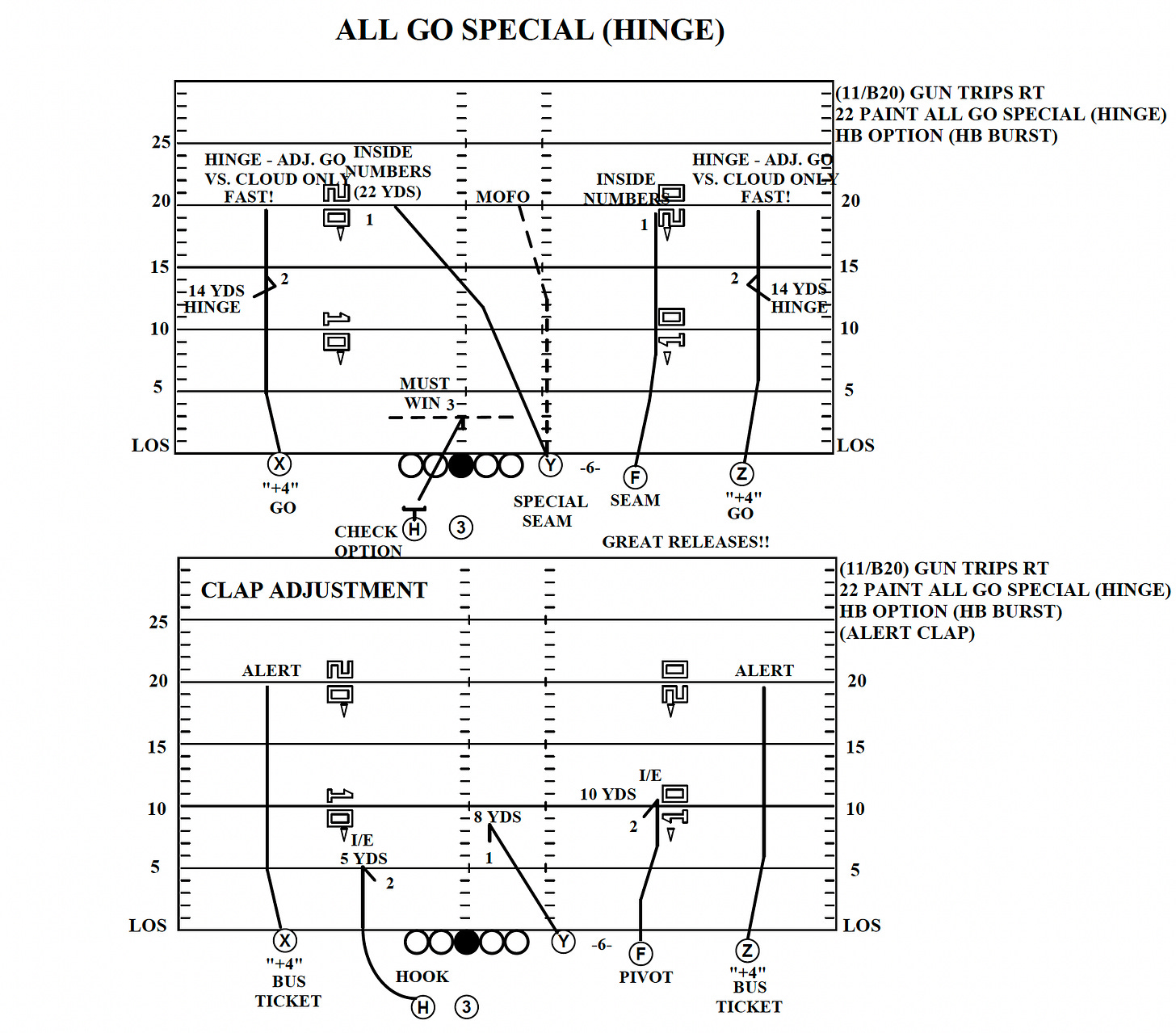

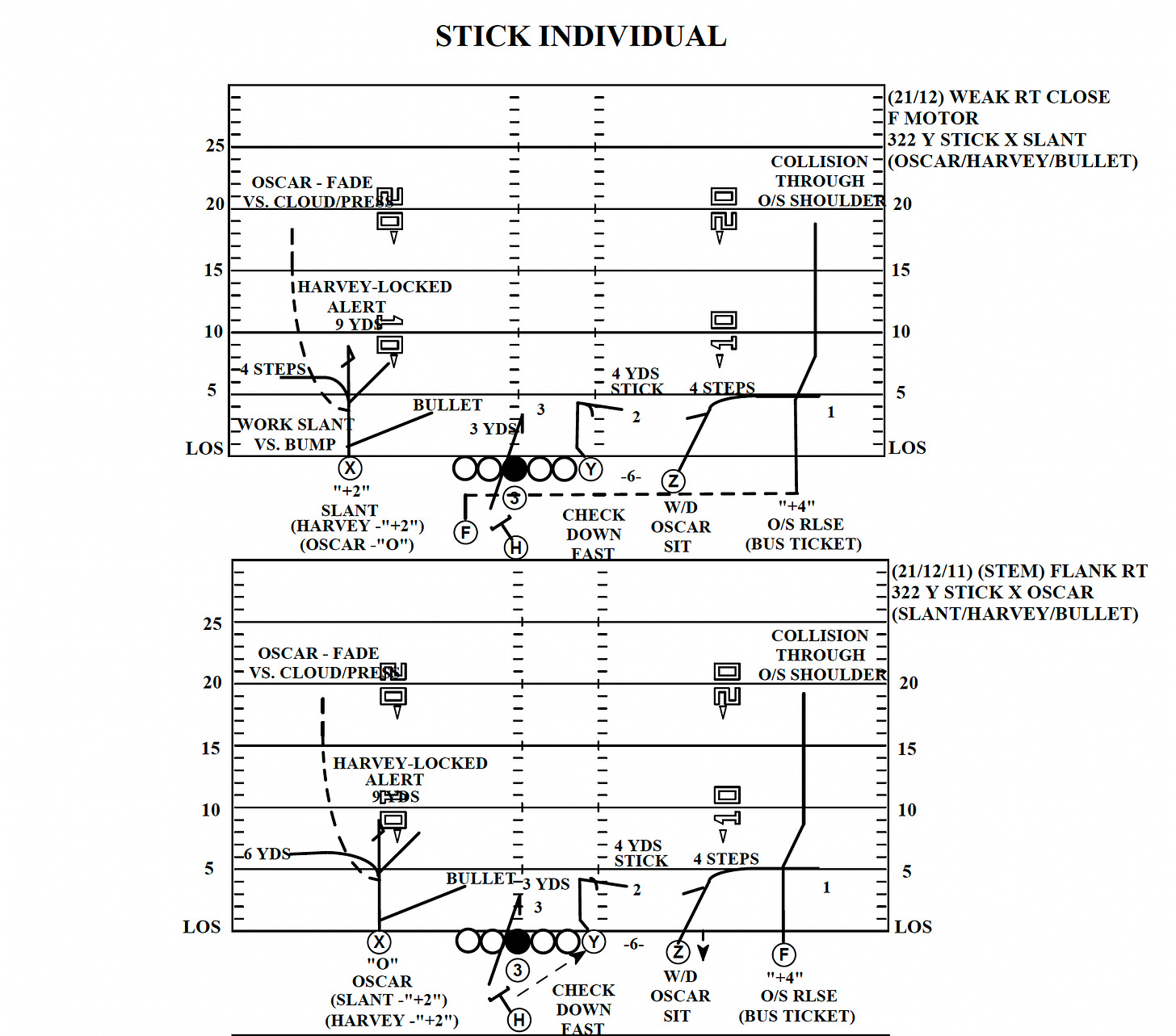

Here is a play from the opening drive of the Packers game. The ball is on the right hash. The Broncos open with a 2x2 receiver stack, motioning into 3x1 at the snap. The formation moves from a balanced (receiver) set to 3x1 into the boundary.

It’s classic pace-and-space, spread-option football. There’s an orbit motion drawing eyes and numbers to the boundary side. From there, it’s an RPO. To that boundary side, it’s a screen. To the field, it’s wide-zone. Nix reads the end-man on the line of scrimmage. If Rashan Gary crashes, Nix will throw the ball out to the perimeter for the screen, putting a running back one-on-one in space on a linebacker with blocking in front. If Gary sits, he can hand the ball off to the running back, attacking the wide side of the field, with the Packers down one in the run fit.

Gary sits, so Nix hands the ball off, and the Broncos rip off a solid early gain.

But there’s more going on under the hood. This is Payton’s first snap of FIB — and comes through motion rather than lining up in it out of the huddle. And he opts for one of the Broncos’ staples, an easy RPO where the quarterback cannot be wrong. But Payton is also looking to gather intel. He wants to know how the Packers will choose to address FIB: will they stick to their typical rules, or do they have a Broncos-specific plan?

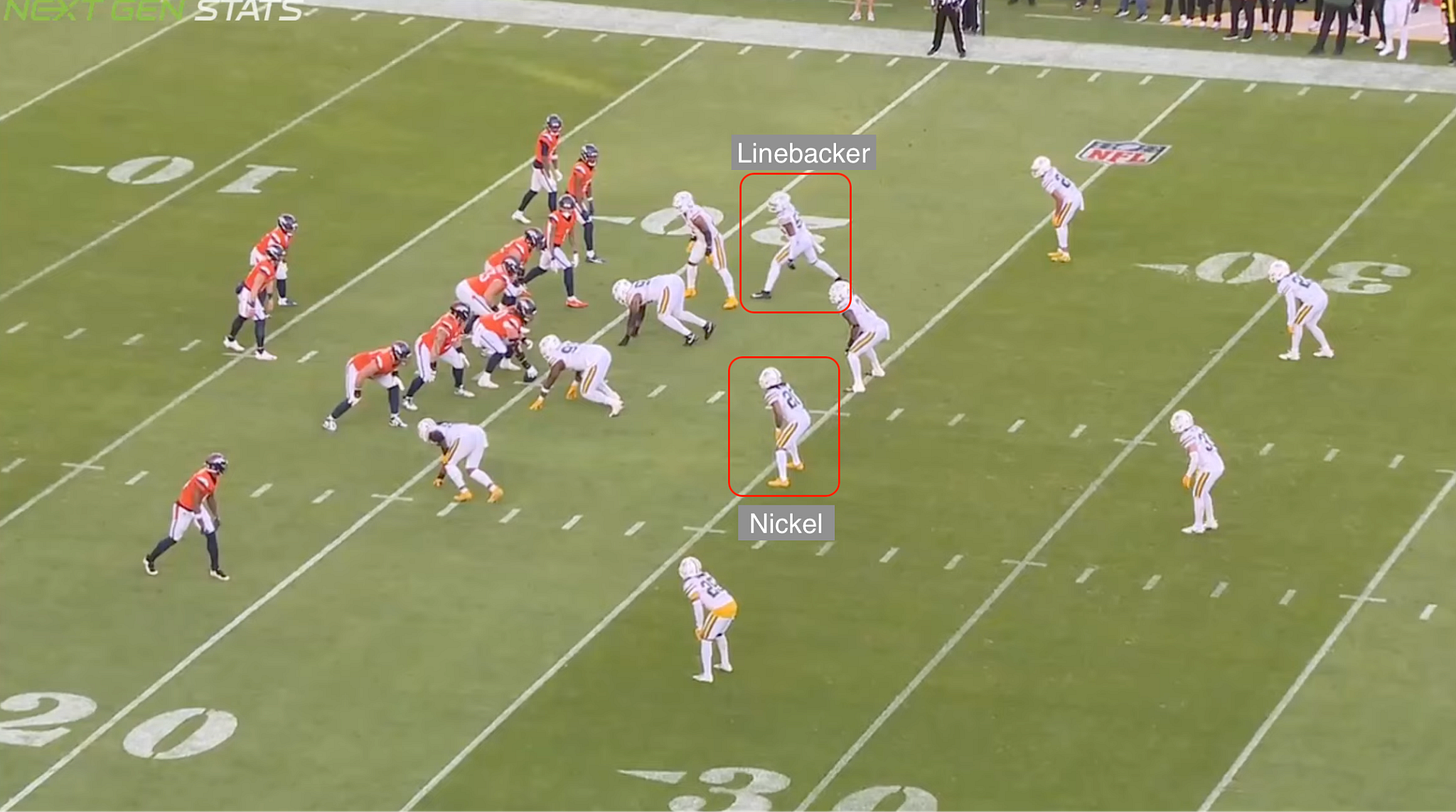

Meaning: Where is the nickel? Do the Packers choose to travel their nickel with the strength of the formation, or do they keep their nickel to the field side and have their linebacker slide over to cover the strength of the formation into the boundary?

Payton has watched the Carolina game, where the Packers faced the most FIB they had before Sunday. He thinks he knows. But he’s on the hunt for information.

As it plays out, you see Green Bay’s choice. They keep nickel defender Javon Bullard to the field side, leaving him in the box as the weakside linebacker to take on the run game, with the linebacker sliding out to the boundary to pick up the #3 receiver (the running back). That’s house money for Payton, who is able to get a lineman up to the second-level cleanly to take on a nickel corner one-on-one. That’s good offense!

So Payton comes back to it later. It’s the same idea: a wide-zone RPO with an attached screen. Again, the Broncos are looking for easy yards while hunting for information on the nickel corner and the linebacker.

Same result. The Packers seem unsure what to do with their nickel and linebacker. Bullard is late to get over. Nix triggers to the screen. The Broncos pick up another solid gain, saved from being more only by Xavier McKinney doing Xavier McKinney stuff on the perimeter.

The first layer is set. Payton has motioned to look and gathered what he needs. Now, he wants to stress test his idea with the dropback game rather than with an RPO. And he wants to do it from a preset formation into the boundary rather than motioning to the thing at the snap.

Pre-snap, the Broncos exit the huddle in a 4x1 formation with the strength to the short side of the field. Again, keep your eyes peeled for the relationship between the nickel and the linebacker (apex defender). How do the Packers want to address FIB? Here’s the answer:

The Nickel is in the box, playing as the weakside linebacker. At the top of the screen, the linebacker is walked out over the cluster of the three receivers, standing on top of the #2 receiver. You can see throughout the rep – from the exit of the huddle up until the ball is snapped – how much the Packers’ defenders are communicating. What did we say this week about FIB? This is a little different. What are our rules? Who has who? What coverage are we playing?

Getting into atypical formations will ordinarily trigger an automatic check for a defense (zone). But there are specific coverage rules within those checks, based on who is lined up where and whether or not the defense wants to play spot-drop zone (keeping vision on the ball) or a match zone (converting into man-coverage depending on the distribution of the routes)

Green Bay comes out in its typical quarters look: two deep safeties with both perimeter corners off the ball at depth. Every Broncos receiver is tight to the formation in a condensed set. It’s giving man-beater vibes. At the bottom of the screen, you can see the cushion that the formation gives to the isolated, single receiver.

At the snap, the Broncos motion. They move the outermost receiver in the cluster and move him over to the isolated side, making him the outermost receiver on the opposite side of the formation. It’s a hinge for the inside receiver and a short curl for the outside guy, eating up all that free grass. The Packers move into a quarter-quarter-half shell, with a giant cushion out to the field. Against man, that #1 receiver to the field can cut inside and slip underneath a screen. Against zone, he sits down and plays one-on-one football in space. Easy yards for Denver. More intel for Payton: the Packers want to play in zone, and the nickel isn’t traveling.

(For now, let’s ignore the illegal downfield blocking from a Broncos receiver)

That’s layer two: quick game out of FIB.

Now, Payton starts to really have fun. He has gathered what he wants early in the down-and-distance, in his own territory. When he crosses the field and gets near the redzone, it’s pay-off time.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Read Optional to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.