The Day Two 22: Offensive skill positions

The most intriguing prospects likely to be available on Day Two of the draft

We are a little over two weeks away from the first night of the draft. Are you giddy? How can you not be? Teams and evaluators are currently finalizing their boards. They’re wargaming — something Jon Ledyard and I have been replicating on a recent run of podcasts.

As I’ve preached throughout the process, there is a confined list of blue-chip, A-plus talent. There is, however, a whole stack of exciting, scheme-specific, B-plus players. The gulf from the 20th player in the class to, say, the 58th is minimal. Most talent evaluators will have somewhere between 16-21 across-the-board first-round grades.

Do you know what that means? Chaos!

When there isn’t a consensus on the top-30ish players overall, and a batch of the top players play non-premier positions, you’re liable for some eyebrow-scorching picks in the top-10 and beyond. Even now, as you read this, as it seems like a consensus is forming around certain position groups, I’m here to tell you: They will be wrong. Opinions on the most valuable positions (quarterback, corner, edge, offensive tackle) are so all over the place that the person who ranks 6th on Outside Evaluator X’s board now could be the sixth pick overall in the draft.

Here is my top-40 board as we head toward the first round:

All 40 will be in first-round consideration. In the week leading up to the draft, I’ll dig into those top prospects and the evaluations, position-by-position.

This week, we’re looking at the most intriguing prospects who will likely be available on Day Two.

Welcome to the Day Two 22: a team of high-upside, maybe-possibly players — some scheme specific. For the purposes of this exercise, we’re ruling out everyone from the above Top 40 board. This is about digging for gold in rounds two and three.

Up first: The offensive skill positions

QB – Hendon Hooker, Tennessee

Hooker has been a late riser in the process, with some prognosticators suggesting he could sneak into the end of the first round, or even rise ahead of Will Levis by the time draft night rolls around. That makes some sense. Hooker is a smart, efficient quarterback. He’s the kind of competitionaholic QB who has worked relentlessly to improve every facet of his game; his load-to-release time is quick and smooth, and improved year-on-year. He does all the little things that add up to wins, and he has enough playmaking chops to get any team excited. His work ethic also just so happens to make him a beloved figure among both players and coaches.

The issues: He is 25-years-old; he played in Josh Heupel’s nonsense, pump-and-dump offense, one with little to no transitive properties to the NFL.

That’s not a knock on Heupel, by the way. If I was running a college program, I’d also embrace a pace-and-space offense with exaggerated receiver splits, and a heavy dose of RPOs. I’d modulate tempos — running from warp speed to slow-mo. And I’d also feature only a handful of concepts dressed up in an equally slender number of ways — most of them being of the you-go-there-I-go-there, one-read-and-go variety. That’s good offense; its impact, everywhere Heupel has been, has been immediate and profound.

Some offenses are expansive. Even if they have foundational components, they’re liable to unfurl one or two new wrinkles every week. Heupel doesn’t work like that. His core philosophy and the crucial concepts have been stress tested… and he runs them… and runs them… and runs them some more.

In some senses, gimmick-laden approach. But it’s hard to argue with the gaudy results.

What is inarguable: It’s not a system that prepares a quarterback for the next level. There were subtle alterations for Hooker — given his experience and skill level — compared to contemporaries who’ve played in Heupel’s system at the college level. Those tweaks pushed the Hooker-Tennessee version a tick closer to the real offense world than the bullshit one Heupel has run in the past. Back in his days with Missouri, Heupel used ‘sleeper’ receivers. In essence, one side of the field one not run routes. The other side would. The defense would drop into coverage, expending energy on every snap. Missouri would target only one side of the field, with those receivers running routes. They would then zoom to the line of scrimmage and target the other side of the field, where the receivers had just been resting. Often, they’d run the exact same concept back-to-back on either side of the field, with the defense trying to keep up with the pace — and to figure out which side of the field housed the sleeper cell.

As pure offense goes, it was nonsense. But it was damn effective. It turned Drew Lock from a bad quarterback with a big arm into a bad quarterback who was selected 42nd overall by the Broncos — and who, stunningly, went on to be wholly unprepared for the pros.

Heupel’s offense isn’t so aesthetically egregious (and strategically ingenious) these days. There are pro concepts within his structure super-spread, split-the-field in half structure. There are pro-throwing windows — and Hooker has shown he can hit them. But it’s still a long, long, long way, in terms of style, communication, and the demands placed on the quarterback both within the working week and on gameday.

It’s not just the RPO, funky play-action designs, either. Everybody runs some version of that these days; it’s just about how far an offense tips along the spectrum. And Hooker has flashed when asked to bounce out of that stuff and to go create some opportunities all on his own. But it’s the design of the offense taken in conjunction with what it asks of the quarterback. Setting projections; adjusting to different concepts week-to-week; working through full-field progressions; the pre-to-post-snap ID process. Even within some super-spread offenses, that stuff is baked in. In Heupel’s world, that’s fluff. The majority is controlled by the staff on the sideline. Reads are predefined. And there’s little change in gameplan-to-gameplan that once a quarterback has mastered the 15 core concepts, they can enter into pre-to-post autopilot mode.

Given the gulf between the Tennessee offense and what’s asked of a quarterback in even the most basic NFL offense, there will be a steep learning curve for Hooker. A team has to decide whether that investment is worth it for a player who could be 27-years-old by the time the light turns on, and who will be pushing up against 30 by the end of his rookie deal.

I like Hooker. His growth is a great story. Were he a plug-and-play, ready-to-go starter, his age wouldn’t be quite the same factor. But with how far he will have to transition from HeupelBall to Pro Football, taking him late on Day One is a stretch. But if there’s a team that’s happy with its veteran quarterback who wants to take a chance on striking gold with a quarterback outside the first round *cough* the Lions *cough*, then betting on Hooker’s intellect, work ethic and release would be a worthwhile gamble. A smart coaching staff with a collection of plus weapons would at least soften the learning curve. But there are precious few spots — Detroit, Minnesota… — where you can find that particular intersection.

RB – Jahmyr Gibbs, Alabama

The battle to be the second running back on the board behind Texas’ Bijan Robinson is a fierce one. If you’re looking for the most complete all-around back, UCLA’s Zach Charbonnet is your guy. If you’re looking for a jolt of electricity, plump for Gibbs.

Now, this is kind of, sort of cheating. Gibbs might sneak into the foot of the first round. And I’m not sure a dynamic playmaker out of Alabama fits with the ethos of the Day Two 22. There is a batch of one-cut-and-go, outside-zone runners who could happily slide into this spot. Every year, there seem to be four-to-five talented backs who wind up going on Day Two and prove to have an immediate impact in the league now that over half the teams are running some variation of the wide-zone-then-boot offense.

There is, once again, a talented cluster of those one-cut-then-explode, wide-zone backs:

DeWayne McBride, UAB

Sean Tucker, Syracuse

Tank Bigsby, Auburn

Zach Evans, Ole Miss

Mo Ibrahim, Minnesota

Travis Dye, USC

Just as teams should take a quarterback every year because of the Year Never Know principle, so, too, should teams running a wide-zone-based system grab a plant-and-fire runner each year late on Day Two or early on Day Three.

But my own personal giddiness around Gibbs has reached a fever pitch that I can no longer put off writing about him.

Gibbs is a pass-catching-first back who offers extreme value as a playmaker out of the backfield and as a matchup weapon in the passing game. Alabama shuffled Gibbs all around the formation, using him as a traditional back, as a receiver out of the backfield, flexed into the slot, and aligned as a perimeter receiver.

As the league has cycled through mini-evolutions over the past decade, embracing different variations of the spread offense, the move tight end has fallen away. What has remained immensely valuable is the moveable running back: someone with the receiving skills to leave the huddle lined up outside as a legitimate receiving threat (not just a catcher, but someone capable of running routes), who can then ‘reload’ back into the formation as a running back. Finding a player who is a threat as a runner on traditional, core running concepts and who can run routes from the backfield, and who is capable of pushing to the perimeter to run an expanded route tree is the secret sauce that all offensive coordinators are looking for – it’s why offensive architects have been so keen to push receivers into the backfield.

Jet motions at-the-snap and movement, in general, fell across the league last year. What has continued to grow, though, is shifting from one formation to another. The volume of ‘reload’ motions — a back setting up out wide and then moving back into the backfield — is on the rise. You typically see this from empty, where the offense starts in an empty set before moving the flexed-out running back back into the backfield — doing so from empty is a bid by the offense to push the defense to reveal its coverage, rotation or pressure pre-snap; often, ‘reloading’ is part of a box-RPO, with the offense spying how many defenders are in the box before deciding to bring the back back in.

If the back is a true threat outside, then he becomes a natural tendency breaker. The offense is able to get all sorts of creative with what it does formationally pre-snap – see the Cowboys, Niners or Packers, who all clowned fools by dancing between different formations by shifting who was in the backfield, and when, pre-snap. From the same grouping, those sides are as liable to take vertical shots targeted to their back (or whoever would wind up in the backfield) as they are slamming the ball inside. A defense is pushed to allocate its resources one way or the other, or having the on-field versatility to adjust on the fly.

If you’re lucky to have two pieces (be it a pair of backs or a wide receiver or Patrick Ricard) who can conceivably exit the huddle in the backfield, then you’re really cooking with gas. Now, you’re able to embrace a wider variety of shifts, prodding and moving pieces continually pre-snap to bleep with the box count and to hunt matchups:

You might, if you’re as dastardly as Andy Reid and Eric Bieniemy, fake a reload motion and turn it into easy buckets in the passing game:

Offensive movement forces defensive communication, the quickest way to miscommunication. Miscommuication leads to easy completions and explosive plays.

A defense must find guys who can line up in multiple spots, or a series of defenders who are comfortable covering whichever dude lines up in front of them — mitigating much of the effect of motioning or shifting. Those creatures don’t grow on trees.

Dalton Kincaid and Luke Musgrave profile as the top ‘move’ weapons in the class, a pair of long-armed, springy tight ends. But Gibbs falls in that category, too. He’s less a pure runner than a moveable weapon — and we should probably evaluate him as such.

As a pure runner, Gibbs has a little more oomph than traditional space weapons, too, which only adds to his value. Defenses will be more prone to ‘buy’ his position in the backfield, whether he lines up their pre-snap or reloads back into the backfield after starting out wide. And a team can always leverage the threat that Gibbs is about to return to the backfield before pushing him to the area he works best: playing out in space.

Alabama’s under Bill O’Brien delighted in getting to four-strong at the snap sets, with four eligibles flooding one side of the field. Rather than exit the huddle in a Quads look, though, O’Brien preferred to use his move piece. He’d align Gibbs to one side of the formation with a trips look the other way – or sometimes sneak Gibbs within the quads. Pre-snap, he’d fake the ‘reload’ into the backfield, only for Gibbs to plant his foot in the ground and go flying out into a great green expanse.

Good coaches find creative ways to attack defenses through formations, motions and shifts. That’s the job. Great players make it possible, though. There’s a reputational advantage with these things, that pushes defenses coordinators and defenders to act in different ways depending on who is doing the moving, to where, and why.

Gibbs is a dynamo in space. He’s a jittery, slippery, explosive runner with the ball in his hands. Alabama leveraged his threat as a receiver to do some pretty things in the motion and shift worlds: they consistently found ways of getting into classic two-back football stuff but through creative presentations by way of motioning or shifting Gibbs from the perimeter or the slot:

But you can forget the fancy stuff, too. Even as a generic check-down option, Gibbs is a spark plug out of the backfield. He forces missed tackles – and turns missed tackles into chunk gains.

Gibbs forced 39 missed tackles on receptions in college, per PFF, averaging 1.83 yards per route run, good for eighth among backs in college football. Gibbs also leads all running backs over the last three seasons with 25 receptions of 15-plus yards and had only two drops from 103 catchable passes in his career.

That’s heady stuff. There might not be a player any team or fan-base will be more excited to draft the Gibbs. The possibilities feel endless. As soon as the card is handed in, the YouTube compilations will be flying, the Twitter cut-ups churning, and the Substack Notes (what a plug!) will be, well, steadily growing. You’ll sit, jaw on the floor, eyes pulsing, wondering how Gibbs isn’t among the handful of most dynamic backs to ever play the position.

The great backs, regardless of body type or skill-set, all have one unifying trait: they gather speed as they climb and cut. There’s no hiccup in their movement. They do not slow down, re-asses or then attack daylight (except, perhaps, for Le’Veon Bell at the peak of his powers, though that was short-lived). They’re constantly moving forwards, even as they bounce and look for openings. Gibbs has it:

The ‘cut’ is not separate from cranking through the gears. They happen in unison:

Take a bad angle, and Gibbs is gone.

It’s not often you find someone who can run a full route tree from the backfield and is capable of moving around the formation as a legitimate receiving threat who can also run between the tackles with a good sense for space and the contours of the defensive front. Gibbs has that feel – and the athleticism to punish defenses with it. Alvin Kamara is probably the closest corollary.

Now, prepare to groan: Gibbs is consistently lost in pass protection. That stuff really matters at the NFL level. It’s how backs get on the field, and why some of the shorter, explosive, backs from the college game fade away before even getting to the pros. Gibbs has the juice and size to be one of the league’s foremost matchup threats in the passing game, but he needs to work on his willingness as a blocker in order to see the field.

At his size — 5-11, 200lbs — Gibbs may never become an every-down, between-the-tackles thumper. But he offers such outsized value in the passing game that in this age of 50 dropbacks per game, teams should be happy to overlook that. They can find a Day Three, undraftable or veteran pickup to do the heavy lifting between the tackles on third-and-short. Finding a back who can break some of the matchup math and tip the scales in the favor of your quarterback in the passing game is more valuable.

WR – Rashee Rice, SMU

Confession time: I’ve spent the last two years rethinking my approach to receiver evaluations. I checked myself into an Evaluator Clinic and secluded myself in a dark room. What followed: Introspection and self-flagellation. Why, oh why, did you like Laquon Treadwell? I went cold turkey. No more JJ Arcega Whiteside’s.

I returned from the darkness having found the light: bank on the guys who get open.

I realized that too much of my focus was being placed on the mechanics of the receiver position. I focused on each individual tree, too often missing the forest. All that matters, in the end, is whether the guy gets open or not. The hows and the whys are somewhat important, depending on the schematic makeup of the offense. But any offense can shapeshift to include a fella who is able to uncover from man-coverage or who consistently finds the soft spots in zones.

So it is with great regret that I report a minor relapse: Rashee Rice has my ears perked.

I wouldn’t consider myself sold on Rice. This whole receiver class oscillates between ‘meh’ and ‘oh, okay, he’s kind of interesting’. Within that context, Rice stands out: He’s an explosive leaper who is a true vertical threat. He isn’t an in-out, twitchy route runner. He doesn’t create as much separation as consistently as you would like. But he has otherworldly body control, and strength at the point of the catch. He can twist and contort in the air even as being dinged by defenders, and he can create throwing angles for quarterbacks that very few players in the league can replicate.

Concerns about his all-around athleticism were obliterated at the Combine. Rice leapt out of the Lucas Oil ceiling, finishing in the 93rd percentile with his ten-yard split, in the 95th percentile in his vertical leap and in the 85th percentile in the broad jump. The upshot: The explosive leaper on tape confirmed his athletic chops when jumping and running in his pajamas. He’s not a sprinter. He’s not swift in and out of breaks. But he’s a rebounder who can stuff a put-back with the best of them.

Good Lawd. That, right there, is the Rice experience. Slow off the snap. Quicker in second-gear than revving up in first. Doesn’t look open. Looks sluggish. Dunks on the corner. Big play.

Getting open can often look like hard work. Rice led the nation in targets and grabs last season, by a decent amount. But almost half of his catches were contested — Rice finished with a 48.5% contested catch rate, per PFF. Rice can be languid in his movements. Routes that should have some snap to them become elongated:

Sometimes, he looks bored with the process, with the details… or tired… or both. Just toss the ball to a spot where only I can go and get it and I’ll bring it down. He finished 2022 with a wince-inducing 8.3% drop rate last season — the majority of which were concentration drops rather than defenders dislodging him at the catch point. Rice had the largest route share of any receiver in the nation last year, playing in SMU’s turbo-charged offense. Perhaps on a more manageable diet, there’s an extra bounce in his step.

Some of his closest athletic comparisons, per Mockdraftable: Nate Burrelson; Brandon Ayiuk; Davante Adams. That feels right, save for Adams. Ayiuk has developed into a true, line-him-up-anywhere, watch-him-get-open, one-on-one star, but he started his career as the ideal second foil whose skills fit within the framework of an offense, rather than him winning independently.

Maybe that’s Rice’s future. This receiver class features a number of 2’s and 3’s. And if you’re taking a #2 or a #3, it’s best to wait until rounds two or three. Rice might be limited, but he brings some upside. He averaged 14 yards per catch last season, despite lacking the top-end speed to be a true homerun threat or a genuine after-the-catch creator.

And he’s not just a vertical menace. Rice is excellent at teasing the threat of verticallity to cut underneath. He loves to sell the vertical stem before attacking back inside or returning to the ball:

So, we have a receiver who doesn’t get open a ton, and when he does, he is prone to dropping the ball. But old habits die hard. There’s something there. Dropping prime Blake Griffin on an offense already blessed with a pair of slippery route runners would be a nice third banana. Building out a receiving room with different body types and skill-sets is what teams are looking for; using Rice as a power-slot, someone who can press vertically from cut split and tight alignments fits with the league’s micro-trend.

Rice won’t be a number-one option at the next level. He won’t be a game-breaker. But he can be a reliable second or third option; someone whose game will be elevated by playing with a better quarterback. Slot him next to an all-around superstar (Justin Jefferson) or a true speedster and Rice can be the ideal two in a one-two tandem. The floor may be limited, but Rice has a particular skill you cannot teach: He can jump over the back of defenders, he can leap in traffic, he can rejig his body while in flight, and he locates the ball. That’s valuable.

WR – AT Perry, Wake Forest

This year’s top receiver prospects are all on the smaller side. Here’s how the class stacks up:

Quentin Johnston, TCU, 6-2, 208lbs

Jaxon Smith-Njigba, Ohio State, 6-1, 196lbs

Jordan Addison, USC, 5-11, 173lbs

Zay Flowers, Boston College, 5-9, 182lbs

Jalin Hyatt, Tennessee, 6-1, 176lbs

Josh Downs, North Carolina, 5-8, 171lbs

Marvin Mimms Jr., Oklahoma, 5-10, 183lbs

Nathaniel Dell, Houston, 5-8, 165lbs

Kayshon Boutte, LSU, 5-11, 195lb

Rashee Rice, 6-0, 204lbs

We’ve got some bowling balls. We’ve got some string beans. Even Quentin Johnston, the thickest, widest, longest, heaviest receiver among the first-round crop, falls into the 76th percentile in height and in the 64th percentile in weight. It’s a light, short class.

Then there are the bigger guys:

Jonathan Mingo, Ole Miss, 6-1, 220lbs

Cedric Tillman, Tennessee, 6-3, 213lbs

AT Perry, Wake Forest, 6-3, 198lbs

With a slender crop of receivers, Mingo, Tillman, and Perry have all seen their stocks inflated throughout the process. Talk of one of the bigger boys climbing into the back-end of the first-round has been rampant for a month.

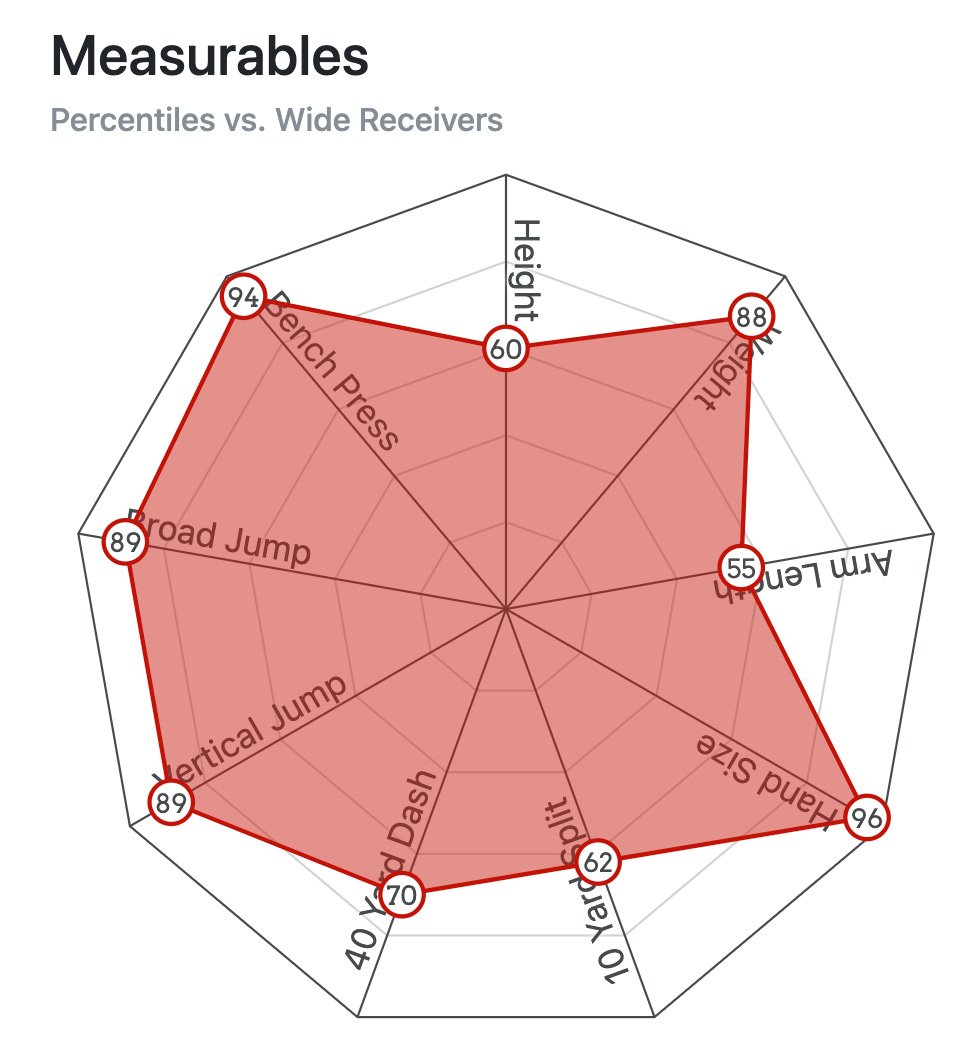

Teams want size and speed. That’s just the way it is. As classic ‘X’ body types go (though those are on the wane), only Mingo, Tillman, and Perry match up. There Mockdraftable spider charts tell the story.

Mingo

Tillman

Perry

Tillman is talented. He also tested as a good-not-great athlete across the board. The apex version of Tillman would be Keenan Allen, a quicker-than-fast perimeter receiver who wins with hops and wiggle. The downside is Amara Darboh or Zach Pascal: A good third or fourth receiver who struggles to consistently uncover from sticky coverage.

Mingo is a long-striding vertical threat who struggles to decelerate and separate late in the route. If he’s not open and burning early, he’s in trouble.

Among the lankier group, Perry stands out. He’s 6-3, 198lbs, which isn’t giant but stands out among this class. Perry has a little more juice. There is the same downside as Tillman: Someone who struggles to consistently separate vs. man-coverage. But he has the bounce to climb over corners. Think DeVante Parker or George Pickens.

Perry is better late in the route. He knows all the little tricks to dislodge covering corners from their spot to create just enough daylight to haul in a target. He’s developed veteran moves before he’s even entered the league. There’s some sloppiness in his get-off and in his route running in general, but there’s a refinement late in the rep that will give him a shot to make an impact early in his career.

Whereas Tillman and Mingo played in differing variations of the super-spread, which limited how much they were pressed at the line of scrimmage, Perry faced a ton of press.

Wake Forest runs a kooky offense, featuring a slow-mesh concept and a battery of RPOs. That, typically, is viewed as a knock on rookie receivers. Life comes easy to them. The scheme gets them open. But that’s. The best way to slow down an RPO-dense attack is to push the quarterback into one of the reads but then have the correct answer for that read. One style: pressing the holy hell out of receivers. Defenses will signal a ‘pass’ read to the quarterback by fitting up against the run early but have their corners beat the crap out of receivers on the perimeter, dislodging them from their spots and throwing off the timing of the ‘P’ in the RPO option.

Perry showed a knack for separating versus press. He was happy to win the hand fight or to use his bulk to lean on corners early in the rep before separating as the ball was on its way. He doesn’t torch corners off the line, but he finds ways to win.

There should be more to come at the next level. Perry has a ridiculous wingspan (6-foot-10) and a deep speed that he should have put to better use in college. Consistency was lacking; sometimes his effort waned. But there’s a talent in there to mold, one with enough nuance to his game and high-end traits that he’s worth betting on among the crop of so-so bigger-bodied receivers in this class.

TE – Sam LaPorta, Iowa

LaPorta was the focal point of a truly awful Iowa passing game. He finished with 18 more receptions than any other Hawkeye weapon in 2021 and 24 more in 2022. Despite that, LaPorta is still raw as a route runner. He’s not a technician; he’s a bulldozer. But LaPorta is electric after the catch. He can break tackles and wriggle by smaller, agile defenders in the open field. It feels like his best football will be in front of him with a competent passing attack.

The issue is how much he will see the field. LaPorta is small by modern tight ends standard. He doesn’t rock anyone in the run game – and he lacks the length to be able to take a more subtle approach to the blocking world. Unless he’s playing fierce, he’s a net-negative in the run-game.

He profiles as almost all those classic Iowa tight ends do: as a functional sixth lineman in the outside zone world who can then go and create magic in the passing game after the catch. And while we often get carried away by the second portion of that sentence it’s the first part that gives the best of the best wide-zone-then-go tight ends their value. LaPorta has to tighten up as an on-the-move-blocker. He doesn’t have to put a dent in the defensive shell in-line. But there needs to be growth, technically, on the move, allowing him to see more snaps and therefore more opportunities to do what he does best: exploit the middle of the field in the passing game.

LaPorta is not someone who will bounce around the formation. He will play on the line. To unlock the obvious receiving potential, he has to become more engaged and violent at the point-of-attack. Some teams will buy into that as a developmental trait; those that do will have LaPorta at the very top of their tight-end boards.

Even as someone who likes Darnell Washington, and who has three tight ends in my top 28 overall, the value in this class is waiting until early in the second round and trying to snag LaPorta rather than chasing similarly one-dimensional tight ends earlier in the proceedings.

TE – Zach Kuntz, Old Dominion

We’re playing out of a 12-personnel grouping here, because this tight end class is more fun than the receiver group — and we’re embracing the Power Spread around these parts.

Kuntz is a fascinating prospect. In years past, he would have been a buzzy name among the draftnik community. This year… nada.

As noted earlier, we’re moving beyond the mini era of move tight ends. A bunch of tight ends still move and bounce around the formation. But they’re typically siloed between two roles, irrespective of the number of alignments — rather than flexing between every conceivable spot in the formation. Some venture into the backfield in spurts. But, aside from Travis Kelce, and no one is really Travis Kelce, there is not a whole lot of ‘Y’ ISO being run in the league these days — a tight end flexing out as an isolated receiver on one side of the formation. Defenses have caught up; they just cannot stop Kelce.

If you look across the league, there is a dearth of flexible tight ends. The league has moved on from that trend. They get receivers to be receivers – and they have the tight end do all the tight end stuff. They are still mismatch weapons over the middle of the field and in creating after the catch, but there’s less movement around the formation from the highs of the Jimmy Graham-Rob Gronkowski era. The idea of taking a ‘move’ tight end sounds fun in theory until it turns out you just have a bigger, slower receiver who offers you nothing when attached to the line of scrimmage.

The purely vertical, receiver-only tight ends are on their way out. It’s why I have reservations about Dalton Kincaid and Luke Musgrave. At a minimum, a receiver-first tight end has to be able to play horizontally — to be a talented blocker on the move splitting across the formation and to be able to make subtle in-out moves in the middle of the field. If you grab that, then you’re in the Mark Andrews, Dallas Goedert world. If you can get a bulldozer off the ball, too, then you have yourself a George Kittle.

Evan Engram is probably the pivot point. He’s more receiver than tight end at this point in his career. It’s not that you cannot have one of those players. It’s just that you have to have a plan — as the Jags did with Engram this season. Maybe you want to be an offense that’s centered around isolating your receiver away from the formation. Maybe that’s the next mini-evolution within the league and you want to be at the forefront. But the mini-revolution appears to be toward the power-spread, incorporating spread principles within a 12-personnel framework. In that world, there’s no time for a receiver-first passenger at tight end.

Dallas Goedert is the aim. Goedert was a one-dimensional prospect who evolved his game in the league. He was a straightline athlete in college. Everything he did was based on verticality: he was a solid in-line blocker when everything matched up; his route tree was almost laughably vertical. Once he got to the pros, Goedert added to this game. He became one of the top move blockers in the league – and proved he could slice across the formation with the best of them, opening up his own game and the Eagles’ offense with him. The Eagles’ ability to bounce between 11 personnel and 12 personnel using the same spread-centric concepts was part of their secret sauce last season. Much of that fell on the shoulders of Goedert. The team’s o-line may make things sing, but Goedert is at least the rhythm section.

That brings us to Zack Kuntz. Kuntz is one of the freakiest athletes in the draft — at any position.

No need to rub your eyes. Yes, you’re reading that right. Kuntz tested in the 90th percentile or above among tight end prospects in height, the 20-yard shuttle, the broad jump, the vertical jump, and in both the 40-yard dash and his ten-yard split. He also tested out in the 80th percentile or above for arm length and hand size.

Like Goedert as a prospect, he’s a small-school, straight-line athlete. At Old Dominion, he bounced all over the formation. He played in the wing. He played in the slot. He played as an isolated receiver. He played as the middleman in trips formations. He played in-line. He played at the foot of a stack. He played at the top of a stack. He shuffled into the backfield. Draw up a spot on the field, and Kuntz aligned there. There were stretches of games where Kuntz was used exclusively as a perimeter receiver.

Kuntz is an explosive down-the-field weapon. When he plants his foot in the ground and drives at the top of his route, he’s able to find an extra gear, exploding away from the coverage (#80):

For a big player, he moves with unusual suddenness. He knows how to modulate tempos, too — how to set up receivers at one pace before pushing to a different speed as he exits his break:

As a receiver, there’s plenty of promise. The vertical stuff is old hat for Kuntz by now. He’s either bigger or quicker than anyone trying to keep up with him. But there are signs under the hood that there’s enough in-out wiggle for him to play more horizontally. For a tall athlete, he’s not stiff. He is snappy out of his breaks. There are wasted movements, his routes can be inefficient, but there’s an innate twitchiness to his game in and out of breaks:

That’s a common sight on tape — Mp4, really. Kuntz slow plays the early portion of his route. He feigns that he’s going to drive down field, before ducking underneath and breaking back toward the middle of the field. He creates separation. Then he waits… and he waits… and he waits some more. The ball should be out, on the body on the break. It’s not.

In college, Kuntz was hamstrung by sloppy quarterback play that lacked a sense of rhythm and timing. It was a see-it-throw-it offense. When Kuntz pressed vertically and was open, he was targeted. When he crafted room underneath with some subtle act of puppetry, the ball either didn’t arrive or it arrived too late. In a timing-based offense, Kuntz could be a weapon at all three levels.

There’s a clear path to Kuntz being a promising receiving tight end. The question is whether he will ever see the field. Kuntz isn’t just net-negative as a blocker. He’s a downright liability. Developing that side is a must. Again, look around the league. Find all the one-dimensional straight-line zoomers who play attached away from the formation down in and down out? *Tumbleweed*. Even the guys you’re thinking about right now only do it in limited snaps — unless it’s a very specific gameplan situation and that gameplan involves Travis Kelce, Patrick Mahomes and Andy Reid.

And those guys who do flex away from the formation as isolated, one-on-one players earn the right by being gifted, willing blockers when they’re playing inside.

Kuntz often looks disoriented in the run game. He lacks the natural in-line power to move anyone. He is so tall that it’s for him to play with the correct leverage. He leaves his stance upright, making it tough for him to time up his feet, hands, eyes, and pad-level. There is a lack of feel for blocking; he’s often using the incorrect technique for the blocking mechanism; you can see him, visually, straining to just get by, to at least be in the right spot and be involved, rather than arriving at the point-of-attack ready to execute the right technique.

You might not have the leverage. You might not have the correct technique. Deigning to try would help. Kuntz would prefer to turn his back and extend his go-go gadget arms rather than aligning to his target and trying to punish a defender for daring to enter his orbit:

That’s not close to good enough. It’s painful to watch. Somewhere, without knowing it, a shiver just went up Geoff Schwartz’s spine. Dante Scarnecchia is ferociously writing a letter to his local representative. That’s the kind of split-flow assignment that would be mandatory for Kuntz — 10-15 times per game — if he landed in a Goedert-like role within a power spread in the NFL.

Kuntz’s mechanics are haphazard. His evolution is going to be a long process. It’s on Kuntz to become something different — to evolve into a player who can fit into the current demands of the league. Dallas Goedert has shown that is possible. A player can work to redefine the flaws in their game which allow them to then show off the parts that come naturally. And late on Day Two (maybe early day three), in a ho-hum draft class, you’re chasing possibilities.

The Day Two 22 – positions and projections:

QB – Henden Hooker, Tennessee – high second round

RB – Jahymr Gibbs, Alabama – high second round

WR – Rashee Rice, SMU – mid-second round

WR – AT Perry, Wake Forest – late second round

TE – Sam LaPorta, Iowa – high second round

TE – Zack Kuntz, Old Dominion – late third round

OT — ??

OG — ??

C — ??

OG — ??

OT — ??