The gameplan that will define the Super Bowl

Here comes Spags!

How do you go about trying to solve a problem like the Eagles' offense?

There is no other offense in the NFL built quite like Philly’s. They can maul people with the run, pity-patter their way down the field with a rhythmic passing game, or smoke fools with shot plays over the head. And then there’s all the optionality – the pre-snap packaged plays, the RPOs, and the RSOs. Try to slow one avenue, and they’ll puncture you with the other.

All aspects of the offense amplify one another. Put the entire Eagles cocktail together and opposing DCs are left in an impossible bind.

As he heads into Sunday, Big Game Spags and his Chiefs’ defense face a bunch of questions: Do they try to contain Jalen Hurts in the pocket or try to force him out? How much should they blitz? If they do blitz, what paths should they take? Should they blitz or pressure? Can the rookies hold up on the back end enough to be able to pressure? Should they play with three safeties on the field to add extra speed(as they did vs. Cincinnati in the AFC title game) or play with more mass up front? Should they run what they’ve run all season or get wonky against one of the league’s more idiosyncratic offenses?

Most important of all: how the bleep do they slow down the Eagles’ run game and the RPOs that flow from those core rushing concepts?

The Eagles' offense is an amorphous beast. They can twist and contort to whatever is needed on a week-to-week or drive-to-drive basis: They throw on early downs and then punish teams with the run on later downs. They throw to get ahead and then close the deal out with a grinding run game. But those early downs passing concepts are all built out of the threat of the run – RPOs, play-action and dropback concepts that feature one of the oh-so-fearful run actions that the Eagles seem to churn out at a 1,000-yard-per-carry clip.

Defending the Eagles' running and option game requires a defense to either allocate extra resources (leaving them exposed on the back end) or to align in specific ways that play into the hands of Philly’s passing game.

They strain a defense to its mental breaking point before the ball has been snapped, and then drive them off the ball with glee. Only when watching the Eagles is THIS common:

I mean, what are we even doing here? You can almost hear Jeff Stoutland twisting his mustache and snickering as his group carves open another canyon.

Some offensive lines win by hammering a front off the ball. Some win through angles and leverage. Some are aided by the scheme, option designs freezing defenders and buying a beat, space, or allowing a group to overload one side of the formation. The Eagles have mastered all three.

Philly can win in any way. But it’s the distinctive RPO and run-option packages that serve as the foundation for all that is right and good about an offense that has proven to be the most difficult offense to gameplan for in the league.

Here’s the issue that has plagued opposing DCs all season: The correct structural solution to the problems presented by the Eagles' generic, base concepts exposes the defense against the team’s more sophisticated option designs – or leaves them having to play one-on-one on the back end in coverage… against AJ Brown, DeVonta Smith, Dallas Goedert and on and on. Neither is a good idea.

Take the most universal of option designs: A vintage inside-zone read. You know the one: the quarterback reads the end man on the line of scrimmage, and if the defender crashes, the quarterback keeps the ball and takes off. If the defender surfs it, sitting down in his spot, the QB hands the ball off for an inside zone run. There’s nothing to it. Every team, on every continent, has it as a day-one install.

Defending it is fairly rudimentary, too. The point of the play is to target the B-Gaps. A defense closes those bubbles by clogging the interior of the line pre-snap – using an interior three in a Bear front or running a hybridized front featuring a 2i away from the back – or fast-fitting at the snap with a quick plugger attacking the vacated spot. To muddy the ‘option’ read at the second level, a defense can exchange gaps in the run fit, an edge defender crashing inside while a defender lined up across from an interior gap scrapes to the outside. Things get fuzzy for the quarterback as they try to figure out whether to keep the ball or hand it off. The end is crashing, I’m going to keep it. Oh bleep, there’s the linebacker flowing around the edge.

It might not work. Your players might get beat. The rest of the line might get blasted to the moon. But, for the coach, there’s a logical, structural solution to the problem. Job done.

Not against the Eagles. Align with your 2i against Philly’s front in the hope of bouncing an interior run, and they’ll pin you with Landon Dickerson and fold Kelce around – Kelce can then skip then kick out the exchanging linebacker.

The wonder of Philly’s power-spread – the beauty of being able to pull all five linemen individually (or as part of a collective) is that there are always solutions to pre-snap structural issues. All options are available at all times – and with Hurts a threat to run, they’re able to pinch an extra gap, either forcing the defense to push an extra defender in the box or conceding grass to the top run game in the league.

Oof.

Oh, and that’s before you get to the horizontal RPOs and the vertical RPOs, which put an extra stretch (physically and mentally on the defense).

There’s no better example than the Eagles’ slide RPO package. They’ve dunked all over the league this season with a fairly rudimentary slide-based RPO run from the wing. The core mechanics are pretty basic: Jalen Hurts reads the end man on the line of scrimmage (EMOL); the wing player slides across the formation at the snap; if the EMOL runs with the wing player, Hurts has a two-way option, to either give the ball to the dive back or to take off as a runner himself; if the EMOL plays the quarterback, Hurts flips the ball to the wing receiver charging into space on the move.

It’s a three-way option that achieves three things: It options the most dangerous pass-rusher on the opposing defense, neutering the defense's best path to a negative play; it puts the ball in Hurts’ hand with a two-way go in short-yardage situations, to throw the ball or to use his legs; it gets the receiver catching the ball on the move to the perimeter.

Indecision is death for a defense. Fixate on every option, and you end up guarding none. Philly put Micah Parsons – the apex of the apex defenders – in a blender by consistently optioning him on first-level RPO reads, forcing him to pat his feet or shuffle quickly to match the slide route rather than barreling toward the backfield. It’s a concept that consistently eliminates the defense's biggest difference-maker. On neutral downs, that wouldn’t be the end of the world. Need a yard or two, though, and it makes all the difference.

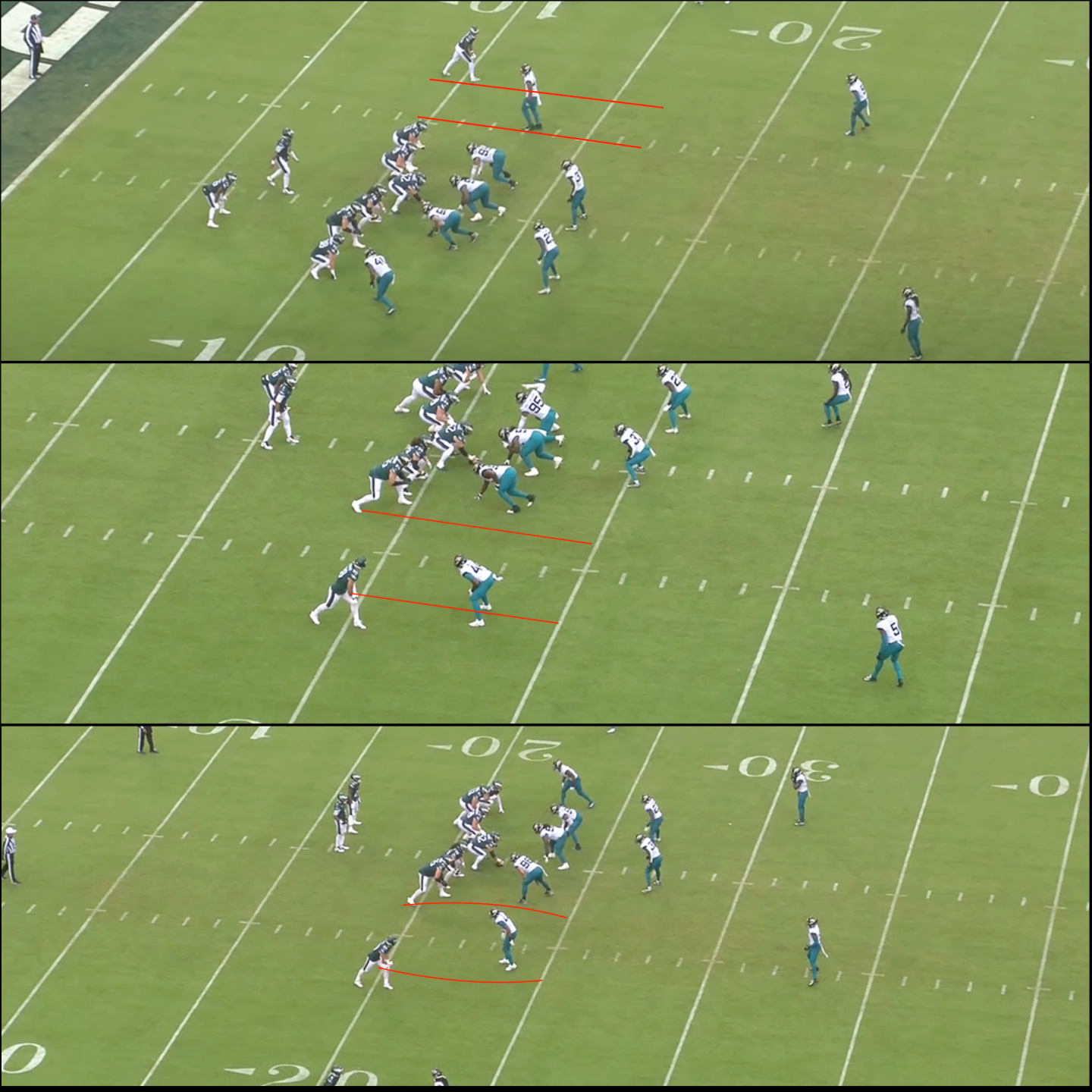

Nick Sirianni and Shane Steichen have iterated on the base concept all season. After launching the concept in an 11-personnel form, with AJ Brown rolling into the wing spot, typically on some kind of motion, they’ve added it into their 12-personnel package. If you thought there was no stopping it before, conceptually, watch this:

Have you stopped giggling yet? I haven’t. How do Sirianni and Steichen resist the urge to call this every bleeping down?

That’s the give to the dive man. Goedert’s movement forces communication among the defense and draws a corner into the center of the line of scrimmage, leaving a tidy surface for the left side of the Eagles’ line to barrel over the front. The running back walked in untouched.

The second option: The flip to Goedert on the slide route. The initial action and read freezes three defenders: The deepest corner, a safety walked down in the box, and the EMOL.

Freeze that and you can see the walk-in touchdown before Hurts has even committed to letting the ball go – you could talk yourself into two of the three options scoring on that same design at any given time.

Hurts pulls the ball. The end-man freezes. Hurts flips it to the slide route. Touchdown.

What do you do as a defense? Blitz the wing? Overload the weakside, as the Giants tried? Commit three guys to the backfield – one to tag Hurts, one the slide, one the back? That leaves AJ Brown and Devonta Smith one-on-one up top, in a stacked formation that allows them to effortlessly pick the man coverage… and that is not good.

That are no easy answers. Scratch that. There are no answers.

The smashmouth-spread — running spread concepts from heavy personnel groupings and ‘heavy’ concepts (gap-oriented runs) from slender personnel groupings — is the ideal modern offense. What Nick Sirianni, Shane Steichen, and Jalen Hurts have constructed this year is bordering on offensive nirvana.

Trying to dial or a recipe that contains all that is… well… tough. The Eagles rank 3rd in EPA per play, 1st in rush EPA, and first in my totally fictitious coach-yelling-what-the-fuck-are-we-going-to-do-to-the-sky metric.

Some offenses present a challenge because they’re so overwhelmingly talented; others because they’re schematically flawless, with counters built into any potential defensive counter. The Eagles have married the two and bludgeoned all in the way.

The only area they’ve struggled all season is in third-and-long. But that requires, you know, a team to win on early downs to force the Eagles out of easy-conversion range. And that requires solving the impossible run-down riddle.

Canvas through the tape of how defenses have set up against the Eagles this season and you can be forgiven for slamming the laptop shut and tossing it into the ocean. Everyone has struggled vs. Philly’s brand of organized disorder. The only time they’ve driven into a ditch is when they’ve coughed up turnovers. Otherwise, they’ve been a relentless machine.

The roots of the Eagles’ offense can be found in all the fun-and-games that the Big 12 has run over the past two decades. Nick Sirianni and his staff dress up their concepts in all-manner of ways, using as much formational diversity as any offense in the league. But the concepts – the post-snap picture of where the players wind up on the field – remain the same.

The best way for a defense to counter the Chiefs’ Big 12, pace-and-space approach by running – shock, horror – Big 12 style defenses, at least at the second and third level. In that way, the structure is right. The process is good, even if the outcome can often remain the same: They get clubbed over the head. Spagnuolo confirmed this week he has spent time with Urban Meyer as well as the staffs at Kentucky and Alabama to try to figure out the best way to approach defending gap-oriented option football.

Perhaps the best blueprint was the Jaguars' outing in Week Four. The Jags were creative with moving and stemming their front pre-snap to blur the give-keep read for Hurts:

They messed with the box count, aligning with a lightened box pre-snap to before creeping an extra defender into the box at the snap. Hurts took the pre-snap bait and ran the ball into a congested box.

It was a shrewd plan from Jags DC Mike Caldwell: Make the box count murky the read, tempt the Eagles to run, and then fast fit to a five-man front, while maintaining a two-deep safety shell to to try to put a lid on any explosive shots down the field.

Caldwell used Travon Walker and Josh Allen as box-in, box-out defenders to blur the pre-snap picture for Hurts.

Using a half-in, half-out box defender, known in coach parlance as an ‘Apex’ cover down. A ‘cover down’ refers to the relationship between the defense’s overhang defender (the player on the edge of the defensive formation, typically) and the slot (or inside) receiver.

The most used cover down for a quarters-based defense is the apex – a defender aligned in the corridor between the tackle and the slot receiever. The linebacker or safety or whoever is the overhang splits the difference between the inside receiver and the line of scrimmage, lining up riggggghtttt on the outskirts of the box. He’s kind of in the box, he’s kind of not, which makes it tricky for the offensive line and the quarterback is trying to figure out who should be blocking who in the run-game – and whether or not (in pre-snap RPOs), they should check to the run or pass.

Aligning in such a way is designed to force the ball to the perimeter. The defense wants the offense to push the ball outside, to quick trigger throws to the perimeter on screens and stop routes. From there, it comes down to blocking and tackling in space. And it forces an offense to play laterally rather than vertically.

Against the Eagles, it also allows a big body to get body presence on any quick, in-breaking RPOs — to disrupt the timing of the pass element. The majority of the Eagles’ RPO attack (like all RPOs) are centered around the slant, glance and snag routes. They’re boom-boom plays: either the run hits or the ball is out ASA-and-P to a receiver running a quick in-breaker with oodles of grass ahead. Adding doubt — adding beats — represents a win for the defense.

Planting a defender in that corridor both messes with the pre-snap read and sinks someone right on the in-breaking landmark, forcing the offense to either take push the ball to the perimeter, to run deeper-breaking options (which add more time), or to shift the plan of attack altogether.

It was effective. Allen and Walker would consistently align in the Apex spot before strolling up to the line at the snap – on some snaps they stayed put; on others they crept. At all times, they impact the quick-fire RPOs that make up a bulk of the Eagles’ offense. When you’re outmanned in terms of talent, the best a DC can do is limit the opponents' playbook – or to push them out of their comfort zone.

Hurts struggled with his at-the-snap read. Is that guy in the box or not? Is he in the run fit or will the defense jump into some kind of funky rotation post-snap? If Hurts reads him and then someone descends into the low hole and the quarterback pulls the ball to chuck the glance/slant pass, then he’s in trouble. The quick-game, inside-zone tagged with an RPO, was largely ditched against such looks.

A defense can live in that look as long as they’re willing to blend a bunch of different coverage principles on the back end – quarters, two-read, robbing the post, etc. They must present a different picture with their safety rotations so as to not get the apex defender caught out flat-footed if the offense gets a read on what the defender is doing.

Stick in the split-safety, match quarters look, though (as the Jags did) and you’re asking for trouble. Aligning with two-deep safety and creeping the overhang into the box late puts a safety one-on-one with a slot receiver 15-odd yards off the ball in pseudo-man-to-man coverage. Against the Eagles, that could be AJ Brown or DeVonta Smith. Gulp.

Hurts consistently read it out as a ‘give’, leading his back headlong into a wall

Capping the slot is difficult at the best of times. There are more route combinations available inside, and they’re higher percentage throws – and teams are more consistently planting their best playmaker in the most valuable slot. Trying to slow that down without getting a bump at the line of scrimmage with a safety 15 yards off the ball is an ask at the best of times.

Plant a safety one-on-one with Brown down the field with all that grass ahead of him and, well, good luck with that. For the Chiefs to get by, their safeties, Justin Reid, Juan Thornhill, and Bryan Cook will have to have the game of their lives.

(Cook has a chance to be the crucial difference-maker on Sunday. He’s an outstanding read-and-react player, one who can trigger and close in a hurry; he can get cooked in space, but he’s a playmaker on the ball – the Chiefs should stick with their three-safety usage to get Cook on the field and to keep one of their cement footed linebackers off the field)

It’s a question of picking your conflict point. RPOs are about – say it with me – conflicting defenders. By aligning with the apex overhang, the Chiefs can opt to shift the target from their linebackers to their safeties. It’s a risk, but in the aggregate, it’s a risk worth taking.

Messing with the box and crafting one-on-ones vs. the option-game is likely the Chiefs' best shot at pushing the Eagles into third-and-long, which is their only real shot to win the thing on Sunday (even if it’s just to tee up one or two game-altering plays).

It’s one of the few ways that the Spags can dictate the terms to the option world rather than having his group read and react.

The other alternative: blitz the holy hell out of the backfield. The Niners gambled against the Eagles in the NFC Championship by sending all sorts of heat on early downs.

Outside of a whacky scheme, defending a good play design comes down to having a great defensive player along the line of scrimmage. Philly did an outstanding job of eliminating Nick Bosa from the game early on by consistently making him the conflict defender – or making him feel like the conflicted defender early in the rep. They optioned him. They trapped him. They cracked him. (and they ran some tackle overload his way just for good measure). They froze him or crunched him, rather than just having Lane Johnson try to drive him off the ball down in and down out.

One of the top ways to slow down a star get-off-and-go defender is to option them, to force them to stop and think rather than shooting upfield. Freeze a super-duper star pass-rusher, get them patting their feet rather than charging toward the backfield, and that, alone, represents a win for the offense.

The Eagles have form for it. They limited Nick Bosa’s impact (who was admittedly banged up) by consistently optioning him in the run game.

The Niners tried to counter by stunting Bosa in order try to obscure the read for Hurts. And while that brought some success vs. the pass, Philly gobbled it up in the run game.

What was effective: Blitzing. Demeco Ryans gambled against the Eagles’ early-down looks and sent a ton of pressure from deep, trying to overload the backfield exchange. It was a gamble. But it worked.

The Eagles popped some huge runs as they out-gapped themselves but they were also able to limit an otherwise domineering attack by selling out with pressure from depth.

Spags is an all-blitz, all-the-damn-time kind of coach. Running cooky, quirky rotations with all kinds of movement – safeties rolling down then dropping out; linebackers zooming here, there and everywhere – has become his brand. By trying to create chaos at the second level and with different disguises on rotations on the back end, perhaps he can bait Jalen Hurts into a couple of back-breaking turnovers, which might be enough to tip the Chiefs over the top.

Stemming, moving, mugging-then-bouncing, apexing-then-walking, and blitzing-from-depth have proven to be the only schematic tools a DC can use to junk up the Eagles’ free-rolling offense. They aren’t cure-alls, but taken together they’re the best shot at creating the kind of havoc that could tilt the game in the Chiefs’ favor.

If anyone can deliver the right gameplan in the biggest spot, it’s Spagnuolo.