This is Robert Saleh's moment

The Jets are all-in. Can they microwave a championship?

All the preseason focus for the Jets is on Aaron Rodgers and a re-fashioned offense led by the, umm, austere stylings of Nathaniel Hackett.

That’s the way these things go. Rodgers was the biggest acquisition of the offseason. A beleaguered, famous franchise. A game-changing trade. A veteran, star quarterback who’s supposed to help put a young, talented roster over the hump.

Got it.

There’s pressure on the Jets — for the first time in a long time. There’s pressure on Rodgers — a chance to show it was all those silly folks in Green Bay’s fault for past failings, not his. Rodgers has been on his best behavior so far — and will continue to do so until the bullets start flying. He’s in legacy burnishing mode.

There’s pressure on Hackett. Back in the Green Bay days, he served as middle management between Matt LaFleur and Rodgers. LaFleur wanted to do things one way; Rodgers another. Hackett’s job was to find compromise, and he did so to great success. What does that partnership look like with LaFleur out of the equation?

There’s pressure, most of all, on Robert Saleh. The success or failure of the Jets’ title bid will not live with Rodgers (no matter the national fanfare) but with the team’s head coach. Saleh has proven his credentials as a defensive architect, but what about as a program builder? What about running a building? And not just any old building, a championship building. And what about running a championship building with a cantankerous 40-year-old at quarterback and an organization that has loserdom coursing through every inch of its veins?

So far, so good. Saleh’s rah-rah style has buy-in from all the key players. He’s been ruthless, too. He axed his buddy Mike LaFleur to help clear the way for Hackett and Rodgers to rekindle their partnership. It was the first decision of many over the next six months that will tilt the balance of the Jets’ title bid.

And what about his defense? Saleh has to devise six gameplans against the NFL’s division of death: the Bills, Dolphins, and Patriots. He’ll face Justin Herbert and Kellen Moore, Patrick Mahomes and Andy Reid, Jalen Hurts and Nick Sirianni, Dak Prescott and Mike McCarthy and Deshaun Watson and Kevin Stefanski.

On the whole, the Jets’ defense will face ten games against offenses that finished in the top-10 in EPA/play last season – and a couple with the potential to gatecrash that group this season.

There aren’t many bells and whistles to Saleh’s scheme. His excellence as a coach is less about wonky play designs and more about his week-to-week game planning. He sticks to what his side does best, while exposing holes in the opposing offense’s makeup. He finds weaknesses and attacks them… and attacks them… and attacks them some more.

Once he’s hit on what works, he doesn’t overthink things. He doubles down. There’s no let-up. He’s not showing off his schematic acumen down in and down out. He’s running what works, to the point of exhaustion. That’s smart coaching.

Saleh wants to play with four down linemen, rarely blitz, and to sink back into only a handful of coverages. He’s betting on players, not plays; he relies on a core group of concepts dressed up in a couple of different ways, and trusts players to react intuitively in coverage.

Having Sauce Gardner on the back end is a cheat code for such a system. But, well, he does have Sauce Gardner.

It’s hard to overstate the value of Gardner. It’s harder, still, to exaggerate the value of Gardner within Saleh’s specific system. The Jets are dropping seven into coverage over and over again. Gardner allows Saleh to lock off one part of the field. Pair that without the need to blitz, and suddenly you’re cheating two extra players into coverage.

It’s upfront where things take flight. The Jets will deploy a cavalcade of snarling, savvy pass-rushers who play with maniacal effort.

I mean, look at this thing:

Quinnen Williams

Carl Lawson

John Franklin-Myers

Will McDonald IV

Jermaine Johnson

Michael Clemons

Solomon Thomas

Bryce Huff

Yeesh. The Jets have Al Woods and Quinton Jefferson to help snuff out gaps on running downs, and then roll eight deep with pass-rushers of every conceivable style: outside swoopers, out-to-in crunchers, inside maulers, two-way threats. It’s a conveyor belt of get-off pass-rushers. Hand any coach a couple of those guys and they’d be giddy.

Saleh has always run with NASCAR substitutions, rolling pass-rushers on and off the field to make sure everyone is a full-go in every situation. But even his most thorough Niners groups didn’t roll quite this deep. Forget aphorisms on the mirror or Red Bull or getting sunlight on your balls (a real, actual practice that some buffoons – some of my acquaintances included – are embracing) to give a spike of energy. It should only take a glance at his pass-rush depth chart to give Saleh a bolt of electricity in the morning.

Stopping the run from an even front with four strung-out linemen is no mean feat. It takes the collective, and outstanding individual players who can make atypical plays at a typical rate.

The Jets stick to their base no matter how compressed the offensive formation. Two tight ends bunched on the line of scrimmage? No problem. Bringing in extra linemen to attack with a jumbo package? Whatever. A condensed set with everyone packed around the box? We run what we.

It's a style that lends itself to closing down wide-zone-then-boot-oriented offenses, so long as your defense can hang in against the run from those wider four-down looks. Last year, the Jets did. They conceded just 4.7 yards per carry from lighter boxes. In six-man boxes, in their classic 4-2-5 look, they ranked comfortably above a bunch of groups playing out of 5-1 looks or 5-2 looks, who had an extra hat in the run fit early.

Being able to keep your head above water vs. the run in those even looks has an obvious knock-on effect: you’re able to keep an extra guy back in coverage, and get to all the funky two-deep-then-rotate coverage looks that help slow play-action shots.

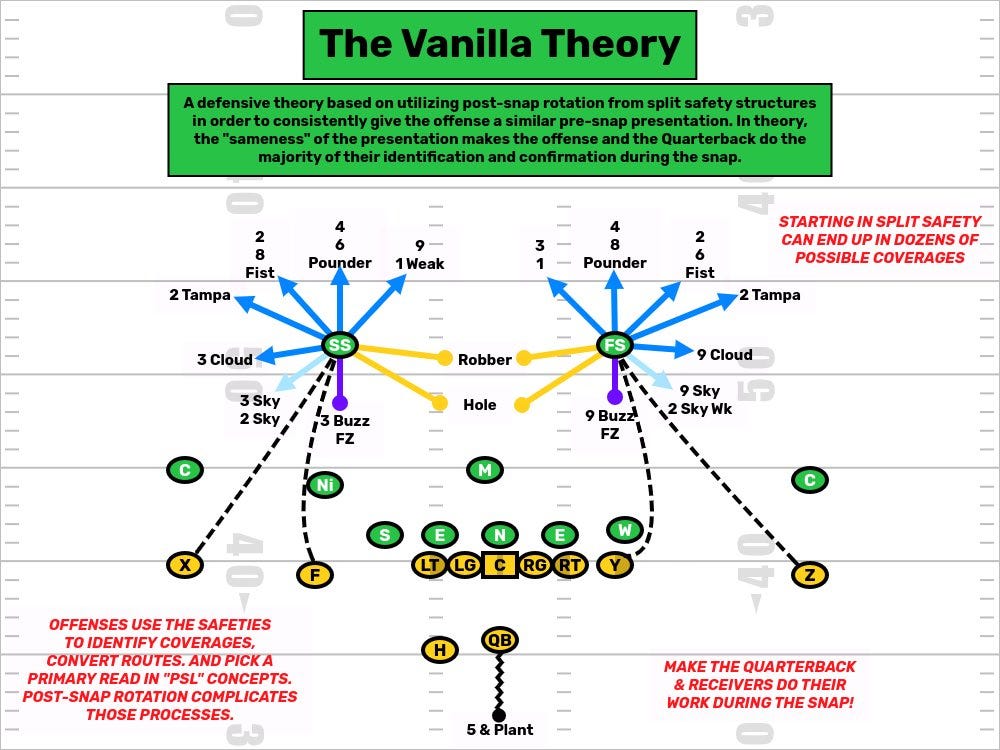

That’s the secret sauce (pun kind of intended) that all defenses are looking for in the Fangio Era. How are you able to keep two safeties deep at the snap so that they can then rotate, put different contours in the defensive shell, and throw off the most potent, efficient way of moving the ball down the field in chunks: play-action.

Saleh’s defense doesn’t need to be dominant from such looks – though they were! – they just have to keep their head above water in order to limit the effectiveness of play-action.

The Jets coughed up just 6.3 yards per coverage snap vs. play-action – thanks, in part, to the excellence of their corners in man-coverage, and thanks, largely to their ability (and comfortability) defending the run from a four-down front.

Slowing the run from four-down fronts serves as the appetizer for the pass-rush.

Saleh is the Grand Marshall of the single-mugging parade, leveraging the deployment of a linebacker to make life easier for the wolves up front to go hunt. Last season, the Jets averaged 2.2 sacks per game with a four-man rush, the second-highest figure in the league. If they don’t match or better that this season, Saleh might think about walking away from this thing altogether. Last year’s unit finished with a 34.1% pressure rate from a four-man rush, well above the championship-level threshold. And they did so without an overly sophisticated style. It’s a group built on stunts, twists, and line movement – and the threat of those out-to-in movements opening up room on the perimeter.

The Jets’ rush plan and coverage are in perfect sync; they’re built front-to-back, the style of pass-rush plan informing the coverage.

Rolling out a steady trove of people destroyers helps. In Williams, Lawson, Franklin-Myers (who was out of his mind last season), Johnson, Clemons, McDonald, Thomas, and Huff they have dominant one-on-one pass-rushers.

The Jets had three players finish in the top-26 of Brandon Thorn’s True Pressure Rate. All three finished in the top-20 in Thorn’s pressure quality ratio: Williams (6th), Lawson (7th), Franklin-Myers (20th). No other team comes close to having more than two crack the top-20 – not even the Cowboys or Eagles. And Saleh will have two other pogo-stick artists flying off the edge this year: second-year man Jermaine Johnson and rookie Will McDonald. Cycling out from your pressure experts to two first-round draft picks is flat-out unfair. McDonald has the potential to be the most impactful rookie in terms of tipping the championship odds, even as a rotational rusher.

This is a front that functions on players, not plays. But Saleh lives out of overloaded fronts and single-mugger sets to help create havoc.

Overloads are as they sound: The defense allocates more rushers to one side of the formation than the other. They run a topsy-turvey front: three down linemen (sometimes more) to one side with a solo lineman to the other.

Saleh likes to toggle between a ‘best on the same side’ style and isolating Carl Lawson — his best edge-rusher — as the player opposite the loaded side of the formation. From there, the fun begins. CJ Mosley (the Jets’ best and most versatile linebacker) will align next to the isolated pass-rusher, mugging one of the interior gaps. That puts the o-line in a bind: do they slide away from the Jets’ most dangerous rusher or commit resources to the side away from the overload? It’s difficult. The Jets having oh-so-many high-level pass-rushers makes it a damn near impossible question.

The single-mugging stuff (more on that later) makes life easier. But the Jets mashed fools from such overloaded looks without having to walk down a linebacker.

Below, the Browns have six potential protectors in the box vs. an overloaded front without the mugger. It’s six vs. four. The Browns should have the numbers and resources to block it up. They opt to slide: the left side fanning man-to-man while the right side of the line waits for things to unfold before picking up their assignments. The Jets have Jacob Martin isolated and their best to the overload side. It's a win pre-snap: they’re getting their best pass-rushers schemed up one-on-ones while a rotational rusher occupies two sets of eyes and arms through alignment. At the snap, it’s a wrap.

The Jets’ front brutalized offensive lines all season long from basic overloads without adding a fifth defender into the discussion.

It’s simple. It’s effective. Saleh used a formational quirk to get favorable matchups in pass protection – the flavor can change week-to-week depending on the opponents and the lineman (or linemen) he wants to isolate. Then he trusted his All-Pro players to do All-Pro things. The result: Carnage.

Where Saleh and the Jets really make their hay, though, is in split fronts. The old-style split-front – think of the Broncos during their Super Bowl run – features two wide-9 techniques (outside the shoulders of the tackle) and two three-techniques (outside the shoulders of the guards) with the spaces on either side of the center vacated.

It's a vintage look for letting loose all the stunts, twists and games that stock NFL playbooks. The center is uncovered. There’s more space to dive-bomb from inside to outside. The center can, at times, feel helpless, waiting for all to reveal itself before he shuffles across to help out one of his guards on an exchange.

Saleh has tagged his split fronts with his beloved single-mugger to mess with the offensive protection. Whether it’s a head-up linebacker over the center (the old Mike Vrabel style) or a mugged defending helping to overload one side of the formation, the goal is the same: to force the offensive line to set itself in a 5-0/man-to-man protection before igniting the dynamite.

So much of modern pass-rush plans fall under a basic premise: use the formation and alignment of the front to dictate the protection (typically man-to-man), remove the guesswork, and then you can attack it.

There are three ways for a defense to get after an offense: Cold, Warm, or Hot Pressures.

They are self-explanatory: A cold pressure is an organic pass-rush, a four (or three) man rush with the defensive line mixing and matching between straight-ahead rushes, stunts, and twists.

A warm pressure means to run a five-across front – be it with five down linemen or mugging one (or more) of the gaps with a linebacker or safety – to force the offense to block with a man-to-man (5-0) blocking scheme. From there, the defense can create matchup chaos. If the defensive line knows you’re blocking man-to-man, their goal is to get the offensive lineman onto different levels in their pass-sets rather than building one solid wall, which ostensibly forces the line to pick itself and opens clean lanes for the rush to come looping home.

Again, the Jets set the protection for the Bills through their formation and alignment. CJ Mosley walks down into the vacated A-Gap, moving from head-up to the right side (from the defensive view) of the center, turning a split-front into a pseudo-overload: three potential rushers to one side, two to the other. Will Mosley drop or blitz?

It doesn’t really matter. The goal is to force the Bills to check to 5-0 protection, to get all those down linemen one-on-one rushes across the board. Mosley’s movement forces the check. At the snap, the Jets have lift-off: Mosley drops, the center goes hunting for work. The Jets are stone-walled on the right side, the Bills exchange it will and are able to stay on one level. The left guard is able to stay out in front. On balance, it’s a win for the offensive line: the Jets weren’t able to fracture the line and plant it on different levels. No bother. It’s one-on-one. Everyone has to win: Bryce Huff comes flying in off the edge, beating Spencer Brown out of his stance. He forces Josh Allen to move up in the pocket to try to evade the rush, right into a parade of bodies looping around. The Jets close.

One way offenses have hit on to counter two-deep defensive shells is to shift into more empty sets, with no one lined up in the backfield. Removing a potential sixth (or seventh) blocker from the protection has made it easier for savvy defenses to manipulate and then attack the protection – the Jets were the second-stingiest defense in the league last season vs. empty formations.

A hot pressure means to bring a fifth or sixth (or seventh!) rusher to the mix. The Jets get to their spicier designs from the same base looks: an overloaded front with the single mugger to the isolated side; or the mugger head-up between the split front. But they major in cold and warm pressures.

You’ve heard it before, but defensive football (schematically) is about adding extra beats to the quarterback’s decision-making process so that pressure can come screaming home – or the quarterback is forced into a mistake. The Jets don’t allow any beats. The pass-rush is too ferocious – and there’s an extra piece back in coverage.

None of this is rocket science. But it’s about timing and execution – and Saleh’s groups always deliver.

The Jets don’t run a diverse set of pressure paths because they don’t need to. But Saleh continues to find subtle ways to tweak things week-to-week to create pressure with four, and to draw up sacks when he tags an extra rusher into the fold. It sounds basic to say a game boils down to whether one team can block the other. But so often that’s the reality.

Dominating out of cold and warm looks only amplifies the times a side decides to bring some heat. When the Jets do bring pressure — a counter to the typical four-man rushes – they’re more liable to hit. When the single mugger is inserted in the five-man pressure, it sows doubt in the offensive line’s mind that he could come every time.

The slightest alterations raise the impact level: A coffee house blitz (a mugger bluffing like they’re dropping and then blitzing); a read-blitz (the mugger reading a lineman before deciding whether to blitz or not).

It’s a simplistic base with enough variance that it bleeps with any given team’s protection schemes. Either you set the protection wrong, miss the blitzer, or sink into the protection the defense wants you to drop into.

And the Jets are liable to bring the mugger late in the count, opening in one look before walking a linebacker down right before the snap, with the same menu available to the defense and less time for the offensive line to communicate or adjust.

To make it simple: it’s charted as a four-man rush but has all the makings (and impacts) of a five-man rush thanks to the pre-snap alignment. Good luck!

When the Jets did add a fifth or sixth rusher to the mix last season, it was a genuine change-up. In 2022, their pressure rate climbed to 48.9% when sending pressure. The team only blitzed on 14.9% of their snaps, the lowest mark in the NFL. But their blitz effectiveness ranked second in the league — and that effectiveness was thanks to the set-up of the non-blitz looks, if you follow. Yes, there is a test at the end of this…

It's tough to deal with. Teams have no idea how to systematically solve such looks – because there isn’t really an innate solution; it comes down to your dudes out-executing theirs. Communication, smarts, chemistry, and talent are the only solutions. And sometimes even that is not enough. From there, it becomes a battle of quarterback vs. coverage – and a seven-man coverage shell at that.

Where some have made the trade-off of an overwhelming down-four with a flaky secondary, the Jets are loaded across the board. How do you win concept vs. coverage, even as the savviest operator, when Sauce Gardener is eliminating one side of the field? What about when DJ Reed, captain of the “Why Don’t We Talk About This Guy More?” All-Star team, is playing picture-perfect press-and-trail coverage on the other side of the field? What about when Michael Carter is beating the ever-loving shit out of everyone across from him in the slot (few demolish the ‘point’ of bunched formations as well as Carter)? What about when Saleh rolls or disguises his coverage?

There are no easy answers. You don’t need many fingers to count the number of guys you’re worried about dicing up a seven-man shell from the pocket and are capable of creating magic when escaping from the pocket: Patrick Mahomes; Jalen Hurts; Joe Burrow; Josh Allen; Justin Herbert; Lamar Jackson. That’s it – that’s the whole list (Trevor Lawrence, Geno Smith, and Dak Prescott could leap into that profile, but their games are slightly different).

The Jets were particularly effective at taking away quick-breaking pass concepts last season. They finished 2nd in EPA against zero, one, and three-step drops from the quarterback. Gardner, Reed, and Carter offered lockdown coverage, the rest of the group pushed depth into the defense, and the pass-rush teed off. On five and seven-step drops, where things can get more frenetic and quarterbacks are more liable to create off-script, they ranked 18th in EPA/play.

It's an ideal playoff profile – the kind that has helped fuel the Niners’ deep playoff charges. Few defenses did a better job of layering their coverage than the Jets last year – adding as many layers and different depths to the coverage as possible. Blending a well-layered back end with a ferocious four-man rush is the championship key. Quarterbacks must be perfect. Or Superhuman. Or Patrick Mahomes.

If not the best defense in the NFL, the Jets should be as near as makes no difference. They already have a championship defensive profile — they can win with a four-man rush; they can hang in man-free coverage on third-downs; they have enough creativity on their staff to scheme up pressures and turnovers — and they’ve added more depth throughout their two-deep.

That’s a nice starting point for a side looking to microwave a title.

Still: Jumping from bottom-feeder to winner-of-it-all is a chasm that no team in recent memory has straddled within 12 months without Tom Brady at the helm of the offense.

Making that kind of leap has less to do with the general talent level or the X’s & O’s than the day-to-day management. Saleh can run a defense with the best of them. How will he go about engineering a championship culture?

Culture is a nebulous term. It’s hard to describe; a kind of know-it-when-you-see-it phenomenon. And it’s often retrofitted to the winners. Did the Warriors have a great culture on their way to back-to-back titles with Kevin Durant? The old culture was still lingering there, under the surface, but two of the team’s stars had a visceral dislike for one another on the daily. They just so happened to have the most gifted starting five in the history of the sport.

A team is a living organism. It grows and develops, suffers setbacks and has to overcome obstacles. The Jets have the talent to make a deep postseason run. On defense, at least, they have the style and the staff. Saleh’s season (and job status) will come down to his handle on the team. How does he cope when the team loses back-to-back games? What about when Sir Moans A Lot takes a snipe at a teammate, on the field or through the media? How does he deliver an us-against-the-world message to a locker room with championship expectations? How does he keep a young roster grounded when they win four on the spin? What if one of the vaunted young pups takes a step back? What if there are early struggles on offense, or his defense falters out of the gate? Does he pivot or stay the course? For a young head coach, it’s a lot.

The Rodgers-led Jets have drawn comparisons to Tom Brady’s final sojourn in Tampa Bay. Brady microwaved a championship culture in Tampa. He brought a gang of his old friends and help turn Loserville into a title town in 12 months. On the loooong list of Brady’s achievements, that’s pretty bleeping high.

But Rodgers is different. It’s all rainbows and sunshine right now. Let’s see where things are at in November or if things get off to a sludgy start.

Then there’s Saleh. Brady arrived in Tampa with Bruce Arians, a long-tenured coach who had piloted late postseason bids in Arizona and had been around a perennial championship culture in Pittsburgh. Saleh has some playoff experience dating back to his time in San Francisco, but he isn’t quite as steeped in experience as Arians.

What is a championship culture? “It’s about building a culture of accountability to each other,” Arians told The Athletic after guiding the Bucs to the Super Bowl. “If you can’t trust anyone, you can’t look yourself in the mirror and make the right decision. You have to be loyal to the cause — the championship.”

That’s a lot of words without saying much. How about this? “Our team worked extremely hard, but we had a tendency to beat ourselves,” Arians continued. “Penalties, bad plays costing you. Finding ways to lose instead of finding ways to win. … Adding Tom Brady this year changed that. We set the culture to another level.”

That’s more practical. “One guy can make a big difference,” Arians said. “With Tom Brady coming in, the way he comes to work, every single day he takes care of himself, the way he prepares, his intensity. The attention to detail. It’s like having another coach on the field. I tried to get a guy pumping his arms coming out of his breaks at receiver, I had been telling him for a month. Tom said the same thing, “Pump your arms,” and he goes, “OK, Tom.”

Does Rodgers have the same elder statesman status in New York? Does Saleh recognize when to pull back, to let the players rule, and when to press the pedal down?

Warriors’ head coach Steve Kerr was around for Michael Jordan’s Bulls’ dynasty before leading the Warriors on their own dynastic run. He talks consistently about culture flowing from the top — not from ownership to front office to coach, but the team’s star player to everyone else in the building.

“The players have to be accepting of coaching, accepting of partnership,” Kerr told The Athletic in 2021. “Michael Jordan really respected Phil. Maybe it was because he played for Dean Smith and recognized the power of a great coach. Phil recognized the power of an alliance between them and had a great respect. Tim Duncan was to ‘Pop’ what Steph Curry is for me. It’s an amazing, generational talent who also happens to be unbelievably humble and amenable to coaching and, if necessary, criticism. Those players in many cases determine whether that culture is going to form, whether they’re really going to allow the coach to implement things he’s looking to do.”

Will Rodgers live the Brady-Jordan-Curry lifestyle in New York? Has he had a personality transplant? And if not, how will Saleh navigate those murky waters?

It’s rare to find a young coach who has jumped so many rungs of the championship ladder in one go. Leaping from fun-upstart to win-or-bust is a chasm that’s tricky for even the most decorated coaches to traverse. Arians made the leap thanks to the Greatest To Ever Do It and a veteran staff. He also did so at 68 years old. Sean McVay, the youngest coach to guide a team to a title, needed a second crack to get the job done — his first side was a purer version of McVay Ball, and the second, the championship one, was more of a compromise.

Look at the list of the last 14 Super Bowl-winning head coaches:

Andy Reid

Sean McVay

Bruce Arians

Andy Reid

Bill Belichick

Doug Pederson

Bill Belichick

Gary Kubiak

Bill Belichick

Pete Carroll

John Harbaugh

Tom Coughlin

Those coaches fall into four camps:

1) Coaches who had been there before as head honchos, either winning or losing (Andy Reid; Sean McVay; Bill Belichick; Tom Coughlin)

2) Second time head coaches with bags of experience (Pete Carroll; Gary Kubiak; Bruce Arians)

3) Coaches whose win was the end product of a team’s traditional cycle: getting close, losing, then coming back to win (John Harbaugh)

4) Doug Pederson

To win it all, Saleh will have to buck a trend. He doesn’t have the time to build in the traditional cycle, to get close and then lose. He doesn’t have the experience of Pete Carroll or Bruce Arians or Gary Kubiak. Any mistakes will be amplified. There can be no learning on the job.

The Jets don’t have the luxury of getting close, reloading, and going again. They’re operating on different timeline. Rodgers may be committed for two years… but who knows? And who knows what that second season will look like for a quarterback who will be 41 years old?

Any hope for a Jets championship will fall on Saleh’s shoulders. Defensively, the Jets should top the charts. They have the players, the scheme, and a warlock of a game planner. Forget about the Hackett-Rodgers dynamic on offense. Even Mr. Blobby could get an Aaron Rodgers offense to sing well enough to keep the team in games. Hackett and Rodgers as a pair might cap the ceiling of what the Jets are able to do, but whether they fall on their face will be more to do with the leadership from on high – does Saleh probe and ask the right questions? Does he enforce things? Does he demand change when change is needed, or leave it to the buddy cop duo to figure everything out on that side of the ball? Does he assert authority over a figure whose every waking second seems wrapped up in the idea that he’s pushing back against structure?

If things aren’t working, does Saleh have the clout to pivot on the fly, and does he have the buy-in from his quarterback and locker room to do so, as Gary Kubiak did with Peyton Manning on the way to the Broncos’ last title?

It’s Saleh’s time. In a loaded conference, having one of the top defensive authors might tip the scales for the Jets. Rodgers will inevitably get the bulk of the credit. In a First Take landscape, that’s how these things go. But if the Jets are to win it all, it’s on Saleh’s shoulders. Can he keep the train on the tracks off the field and continue to roll out a defensive freight train on it?