What will a Russell Wilson-Nathaniel Hackett offense look like, exactly?

How will the Broncos' new head coach fuse his own ideas with Wilson's idiosyncratic style?

Once the initial shock of the Russell Wilson-to-Denver trade wore off, one thing jumped to mind: What exactly will a Nathaniel Hackett-Russell Wilson offense look like?

Well, that and some semi-excitement that the attention-seeker-in-chiefs big-day was gazumped by another wantaway quarterback – only this quarterback really wanted away.

Hackett comes from the brightest, most innovative offensive room in the league. Over the span of three years, Matt LaFleur and Aaron Rodgers set to work redefining what a Rodgers-led offense could look like, and in doing so built the most expansive system in the league. They reset the Packers’ passing game, building on top of the second-phase stylings that Mike McCarthy initially introduced but adding a timing element into the second-phase.

McCarthy was one of the first NFL head coaches (or offensive scheme designers in general) to fully embrace the power of the packaged play. He designed sophisticated ways to utilize the second phase of the offense, the area where Rodgers was most impactful: Designing specific second concepts within a route combination once the first had busted. Rather than receivers darting to the traditional landmarks once Rodgers entered the scramble drill – short, medium, long, hit the sideline – the McCarthy’s group built-in second-concepts that could flow more seamlessly from the first.

Still: there was little timing in the offense. It was a feel offense, relying on Rodgers to move and bounce and to read it out properly, and for the receivers to read and bounce at the same speed; there was a ‘second’ play design built-in, so to speak, but one still reliant on see-it-throw-it football. Too often, it devolved into a mess.

The LaFleur and Hackett group brought more order to the orthodoxy. Rather than building in secondary concepts to the jazz portion of the musical, they paired two concepts within the same concept, pairing quick-game concepts to one side of the field with slower developing intermediate and deeper concepts to the other side of the field.

They brought timing to the second phase. Now, Rodgers’ intent would be to attack in quick-game. But if the quick-hitting concept was taken away, when he moved to the opposite side of the field, as he engaged in his tap-dancing mode, the second concept would still be within the timing and flow of the play. The deeper breaking concepts would just be converging as he moved off the quick-game stuff. It would all be a touch more organic.

Whereas others work deep backward – alert the take-off route and then work the underneath if it’s not there based on the pre-snap coverage shell – the Packers worked in the reverse. They wanted to throw the quick-game concept to keep things moving along, but if it wasn’t there – BOOM – Rodgers flowed seamlessly into a deeper-developing concept attacking the other side of the field.

It was creative. It worked. You know the rest: Back-to-back MVPs and all that.

There were tasty side dishes: the 4x1 formations; the fast motions; the volume of motion-at-the-snap; the single-man bubbles; the force-feeding of their star receiver; concealing their star receiver within the play design; a refocusing on the run-game, and a new road map for how it should function.

At root, though, the LaFleur-Hackett-Rodgers doctrine could be distilled to this: Feature our best. If Davante Adams is uncovered, get him the ball. Who cares how it gets there? Pick it up and throw it to him, let him create. Does Rodgers prefer to tap-dance than play on-time and in-rhythm? Then build that tap-dancing into the rhythm and timing of the play — that way everything is repeatable, rather than relying on the wonder and awe of one man.

How much of that was Hackett responsible for? Reports differ. The fairest assessment appears to be that LaFleur and Rodgers generated a bunch of the macro, theoretical, philosophical ideas and Hackett had to find ways to actually, you know, put it into practice

The most likely answer is this: Little to none. That’s extreme – there will be some. But enough to truly move the needle? To point to a new brand of offense, a brand of Hacket-ism? Unlikely.

Still: The idea of Wilson in a such a well-coordinated, second-phase oriented system (that ‘system’ word is important) is enough to make any football lover all sorts of tingly.

And then you remember this: Russell Wilson runs Russell Wilson’s offense. Period.

The messaging out of Wilson in Seattle over the past two-three-five years – as well as that very vocal fan-base – is that the organization needed to get bolder, to do more, to reinvent. There was the #LetRussCook movement. There was a call to move away from the stale brand of match-three defense.

And they did! Pete Carroll didn’t get enough credit last year for burning it all to the ground and attempting to go again with a radical new style of defense, one built on pre-snap movement and two-deep coverage shells – something I covered in greater detail on a podcast with Matty F. Brown that you can listen to here.

On offense, there has been a willingness to change things, too. From the caveman stylings of Brian Schottenheimer and Darrell Bevell, the Seahawks looked to get younger and slicker by bringing in Shane Waldron from the Rams to run the offense last offseason. But any sense of the Seahawks embracing the confuse-and-clobber style that powered the Jared Goff era Rams did not come to fruition. There were nods and winks to some of the Rams’ style – unbalanced lines, the odd 4x1 set, a slight uptick early in the season in motion, and shifting (but notably not at the snap). But in the main, it was the same old, same old.

There are two reasons: a) defenses finding counters to that style of offense (the Seahawks missed on when they wanted to jump into that particular evolutionary cycle); b) Russell Wilson.

At this point, it’s clear there’s not a Seahawks style or a Schottenheimer style or a Waldron style or a Carroll style. It’s Wilson’s style. His unwillingness to throw over the middle of the field took on meme-level proportions last season. Wilson attempted just two passes per game of 10 yards or more over the middle of the field last year. By comparison, Tom Brady averaged seven such attempts a game, Aaron Rodgers averaged five, Patrick Mahomes is averaging four. In fact, among 34 eligible quarterbacks this season, Wilson ranked 29th in the league in the average number of attempts per game he targets beyond ten yards in the middle of the field. 29th! Russell Wilson!

To play in a Russell Wilson offense means to forfeit the middle of the field, which constricts whatever an offense might like to do. There are only so many nifty route combinations — so many play-action quirks — that a coach can build in to attack the same specific parts when his quarterback voids a huge chunk of the field. It wouldn’t have mattered – seemingly – if the Seahawks had brought in the most radical play designer in the league if Wilson was unwilling to adapt and grow his own game.

Wilson likes to pepper the sidelines with short, sharp throws, betting on his ability to hit what are traditionally low-percentage throws at a high clip – by sticking the ball along the sideline on isolation routes, he’s able to limit turnovers, but often at the cost of sacrificing the middle of the field and all the knock-on benefits that come with stretching the defense in multiple ways.

The Seahawks-Wilson offense was been predictable to the point of lethargy: hammer away with the run-game, toast the sidelines, and then uncork some form of slow-developing shot play.

When gunning deep, it’s all about those sloooow developing route concepts, or Wilson moving and creating all by himself. The timing-based second-level stuff? That’s out. The areas where LaFleur, Hackett, and co. helped channel Rodgers’ game later in his career, bringing some order to Rodgers’ brand of chaos, Wilson has no time (or timing) for that. There aren’t carefully oriented second-phase designs. It’s just Wilson taking a deep drop and letting it rip or creating out of structure thanks his own playmaking chops.

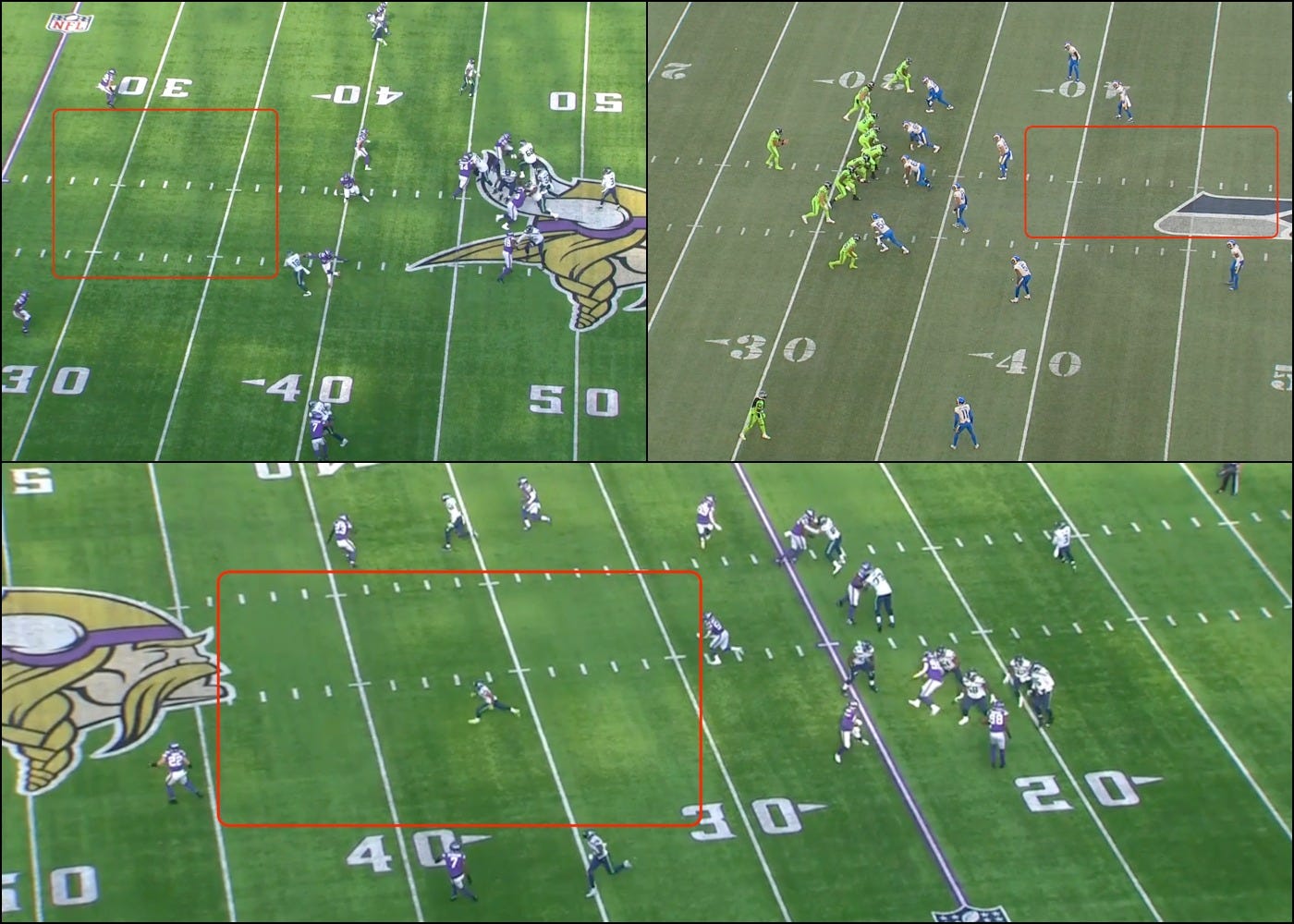

Defenses that have faced Wilson a bunch over the past few years have cottoned on. The Vikings and Rams early in 2021 abandoned the middle of the field, knowing full well that it was better to deploy resources elsewhere. They used Wilson’s worst instincts against himself, fleeing the middle of the field as if it had just coughed in public. Defenses had no interest in burning one of their precious DBs by sliding him into the high-hole when Wilson had no intention of targeting that area anyway.

It worked. Early last year, as Waldron and Wilson were still figuring one another out, there would go some routes, wooshing over the middle of the field, wide open, begging to be hit. Nope. That’s not Wilson’s Way.

This has been a long-running theme to Wilson’s game. It’s why he’s able to limit turnovers. But in playing such a compressed style, defenses are better able to cut off his supply line outside.

There’s some logic to Wilson’s thinking: He just isn’t a great thrower to that area of the field. Call it his height, call it a lack of practice, call it a lack of confidence, call it whatever you want. When he does target that area of the field, the results have been iffy – serving as confirmation bias for a quarterback who could really do without it.

Whenever the Rodgers-LaFleur-Hackett dynamic is discussed, analysts typically fall back on the idea that the coaches ‘made things easier’ for their quarterback. There’s some truth to that – though the real truth is that having Aaron Bleeping Rodgers makes life easy for coaches. One of the overlooked aspects beyond the easy yards they manufactured was addressing Rodgers’ passing radar — and the timing at which he got to certain parts of his passing arsenal.

By the end of the McCarthy era, Rodgers had settled into a similar pattern as Wilson. He took the easy, low percentage stuff outside the numbers. Flick the ball, get on with the game. Deep designs were slow-developing, forcing him to pat the ball and pat the ball. Anything in between was all about his own feel and playmaking chops. He’d bounce out of the quick-hitter, extend and create.

By shifting to the multi-layered approach outlined earlier, LaFleur brought rhythm to a particular area of the field for Rodgers, making him more potent at the second level. And, whaddayaknow, it had a catalyzing impact on every other area of the field: the deep ball was more effective and efficient; quick hitters to the perimeter were that tick easier as defenses looked to cramp the second-level. Suddenly, picking it up and flicking it to Davante Adams on a single-man bubble wasn’t just an efficient play, it was the most efficient play given the pre-snap shell and the matchup — and it was easy.

Can Hackett implement something similar with Wilson, or will the quarterback persist with his own set-up? There’s scope for an interesting mind-meld if the quarterback is, well, up for it. From a skill-set point of view, there’s little to nothing you could ask Rodgers to do that Wilson could not (no duh). But it’s about the want on the part of the former Seattle man. Rodgers embraced evolution; will Wilson?

Compare the two passing maps from Rodgers and Wilson from last season, via the PFF Quarterback Manuel.

First, Rodgers:

Now, Wilson:

Notice the difference? Look at that sea of blue from Wilson directly over the ball, stretching from the line of scrimmage throughout the secondary. And then scan Rdogers’ again. That area, right there, is where he makes hay – and it’s that hay that has the compound effect of opening up everything else.

Rodgers led the league in targets and completions ten-plus yards down the field over the middle of the field last season. Wilson ranked 29th among eligible quarterbacks, a paltry figure by franchise QB standards. He attempted 15 throws of 20-yards or more in the middle of the field, compared to 41 (!) to his left 20-yards downfield and 27 to his right, a total good for fifth in the NFL – and that despite missing playing time.

Wilson’s game has always been built around that deep ball. He takes the easy guff underneath and launches delightful darts down the field to keep the offense chugging along. Last year, however, as defenses vacated the middle to focus on the perimeter, his effectiveness dropped. His adjusted completion percentage (which removes throwaways) ranked 23rd among eligible quarterbacks on throws of 20 yards or more. That put him behind Davis Mills, Tua Tagovailoa, Carson Wentz, and a

fossilized Ben Roethlisberger, hardly a who’s who of Favre-ian gunslingers. And this while 20-yard-plus throws subsumed more of the Wilson offense than ever before:

There is noise in that 2021 figure: it’s a smaller sample size; Wilson’s finger/hand injury had a dramatic impact on his effectiveness over the second half of the season.

Still: As much as the offense needed to adapt and grow heading into last year, so did its pilot. He did not. Wilson then got hurt. Before the Seahawks could blink, the season had slipped away.

And none of this matters! None of it! Because he’s Russell Wilson. And Russell Wilson is freaking awesome! He makes atypical plays typically. He’s crafted himself an offensive ecosystem that makes life unnecessarily hard… and it doesn’t matter; he still torches fools when he’s healthy and is afforded any sort of protection – and when not.

I mean, come on now! That’s a genius at work; it’s a quarterback who breathes momentum into wayward possessions. Over and over and over and over, for a decade now.

Look at those 20-yard-plus figures again. Any notion that Wilson’s deep ball has slipped, that he’s ageing out of that skill, is exaggerated. A whole bunch of those one-year figures is based on environment: the receiving corps a quarterback is working with, the offensive design, how defenses play things. 20-yard attempts were suppressed across the board last season due to defenses shifting en masse to two-deep safety looks pre-snap. And Wilson still posted figures that match up with the majority of his peak years in Seattle.

The idea that he’s slipped there a little is based on comparing 2020 and 2021 to his 2018 season, where he reached supernova levels. To expect a quarterback to repeat 50 percent completion percentage on deep shots, averaging 16.9 yards per attempt with 15 touchdowns to one interception is just unrealistic. That he did that once is bonkers.

The same touch, accuracy, torque that has made him one of the most effective deep-ball throwers of his generation is still all-the-way there:

It’s all so easy for him:

If anything, the issue has been an overreliance on those deep shots at the expense of targeting the intermediate portions of the field. Coaching and effort can only make up so much for a quarterback self-imposing a prison sentence on great chunks of the field.

Hackett might be able to curb some of Wilson’s worst instincts or bring a waft of freshness to the stale Wilson Way. He might not. It probably won’t make a ton of difference. When he is upright and healthy, Wilson is a top-five, create-on-the-go quarterback. And in the era of zone-pressures, creepers, and overloaded looks, as defenses scheme up more free rushers than at any point in league history, a team needs a quarterback who can go and create, who can get a bucket all on their own, no matter the down or distance. Wilson is one of the rare guys you can bank on to do that.

How Wilson looks in a version of the LaFleur-Rodgers offense is a fascinating thought exercise. And yet it will likely prove to be meaningless. Wilson runs what he runs, plays as he plays. All that really matters is that on third-and-medium the Broncos now get to turn to one of the game’s off-script maestros and ask him to ‘go make a play’, and they know he’ll probably make it — and all for the cost of a quartet of draft picks that Denver will soon forget about.

Some other quick thoughts on the deal…

· I thought the Seahawks should have been open to offers from Wilson this summer, but this offer isn’t close to good enough. If you’re going to trade a franchise quarterback, you have to get at least six premier picks or four premier picks and an A-Plus player back. Adding Patrick Surtain Jr. into the deal should have been a redline for Seattle. Shelby Harris and George Fant are fine players; they don’t move the needle on a rebuild. Drew Lock is a throw-in. And for a team with a ropey draft history, save me on the idea they’ll nail all those picks. Four picks sound like a decent amount in the now; once you miss on two it starts to feel awfully thin… all while Wilson is launching bombs in Denver.

· Trading for a franchise quarterback is supposed to hurt. There’s supposed to be pain. A generation of draft picks. Your finest prospect. Something. What in this deal hurts Denver? Unless you fetishize draft picks (and many do), there’s nothing. As best we can tell, all this does is add certainty to the most unpredictable part of the organization. The Broncos were going to sell for in excess of 3 billion whenever the blind auction for its ownership kicks off. That number now feels a little light.

· It’s hard to get away from this: Seattle picked a 71-year-old Pete Carroll to rebuild his defense and lead a wholesale rebuild rather than a 34-year-old quarterback who had led the team to eight top-ten finishes in DVOA. Offensive efficiency is the way to the playoffs in the modern game. The easiest way to establish an efficient offense: have a franchise quarterback. The Seahawks just ripped out the most direct path to the playoffs in favor of a multi-year rebuild headed up by a septuagenarian.

· The Broncos next step is to find a competent right tackle. Making this move allows them to eschew any notion of building for the long-term and to focus on medium-term or year-to-year options. They still have plenty of cap room to work with (close to $20 million). Some of the options that should be on the table: Morgan Moses, who fits in the outside-zone/power hybrid run-system that Hackett ran in Green Bay; Trent Brown, a run-game mauler who can play on the right or left; Joe Noteboom, Andrew Whitworth’s backup in LA is worthy of a look if the Rams do not lock him down before free agency. Noteboom would be a cheap option. Picks are now in short supply, but GM George Patton should still look into the trade market to see if there’s any value out there — he has the means to add a wantaway player for a middling draft pick and then to sign them to a decent extension.