Why the Pistol will be back en vogue

What's old is new again

Editor’s note: I wrote this piece on the anatomy of the Pistol formation in 2022. I was trying to project where the top offensive minds would try to evolve their offenses to approach the changing defensive world that was being thrown in their face. A couple of years later, the Pistol rate is up across the NFL. Two years ago, the average Pistol rate in the NFL was 3%.; five teams had a pistol rate over 5%; only two teams were at over 10%. In 2024, the average rate is 7%; 15 teams (!) are up over 5%, with eight (!!) up over 10%. I’ll check back in on the rates at the end of the season — 31 October, 2024.

If this newsletter has been about anything over the last 12 months, it’s been the ongoing turf war between the wide-zone-then-boot offenses and the two-becomes-one, rotating defenses.

For four years, offenses across the league paired the typical wide-zone structure with condensed splits, deep overs and crossers, and deep-breaking option routes, building on the you-go-here-I-go-there style that was synonymous with the spread and filtering it through the prism of the most proficient run-game in the modern era of the league.

Fun was had by all.

In 2021, defenses fought back.

One of the ruling conversations of the 2021 season was about two-deep defenses. Was that Patrick Mahomes’ kryptonite?!??! Shouty TV personalities certainly seemed to agree so. I mean, just look at the numbers, numpty – of course, the fact that any quarterback’s production declines in the passing game when there are, you know, more defenders covering more space seemed to go consistently uncommented on.

But there was some truth within the discussion. Defenses did shift, en masse, to more two-deep safety sets – an act of survival as much as anything else. And yet, as detailed over the course of last season, more so than sitting in the traditional trapping of a split-safety defense (Cover-2/4/6) it was about starting in a two-deep structure and then rolling to a single-high structure. In short, starting with two deep safeties before moving to a single deep safety.

(Through matching — a hybrid of man/zone coverage — out of Cover 4, ‘quarters match,’ is as prominent as ever before.)

Defensive football has taken on a similar philosophy to that on the offensive side of the ball. Sure, the offense has the luxury of knowing the play-call, but that doesn’t mean that a defense cannot force the terms of engagement. Nor does it mean a defense should be static. In the spread-era (whether a true spread or a traditional offense inspired by spread principles), static is predictable. And predictable is death.

You know the deal. It’s about changing the pre- to post-snap picture. Offenses get pre-snap motions and shifts. That’s what allows them to create confusion and chaos on defense. Movement forces communication. And, by forcing communication, you wind up with miscommunication.

Rolling on defense is the defensive equivalent. As the wide-zone-then-boot systems came to hold a monopoly on the league, one thing stood out above all: Offenses used the ‘boot’ portion to detonate explosives. In the olden times, a boot design fell under the concept of the ‘waggle’, a short-yardage, chain-moving play. Not anymore. No. If an offense is going to go through the hassle of the play-fake, of shifting the launch point, of baiting the linebackers, of forcing a safety to hesitate, of tempting the other safety up into the box, you best believe they’re taking a deep shot.

How do you slow quick-trigger quarterbacks spinning out of the fake exchange and slinging the ball to the streaking deep over route? You add extra levels into the defense. You change the picture. You line up one way when the quarterback is facing you and then shapeshift when he turns his back.

I detailed a year ago how defenses were looking to counter the boot shots. Mostly: Playing match-quarters coverage, sinking into ever-increasing shells, and focusing on ‘greenlighting’ the quarterback, even when he was handing the ball off and not faking it.

Yet, while that basic premise held true throughout the season, the most effective part of the defensive fightback was changing the pre- to post-snap picture. It was not about the specific coverage (though six-weak was typically the call of choice) but about defensive coordinators shifting their mindsets. A single-high coach could still get to their entire coverage menu. But, rather than getting to the same shell through a static look, better to roll one of the safeties, to get players playing ‘top down’ and to use the offensive design against itself.

It's pretty simple: As the quarterback turns his back to carry out a play-fake, he cannot see what’s going on behind him. As the quarterback turns around to scan-then-fire, the shell he saw at the snap is different from the one he sees after he’s carried out his fake. Extra beats to the decision-making process give pass-rushers a better chance of getting to him, forcing the quarterback to speed up his clock, and forcing mistakes.

(Add that to the volume of zone-pressures and creepers, which use the same mindset, and it’s easy to see why offenses fell away last year)

It worked. Expected Points Added (EPA) -- the best measure of play and drive value -- fell across the league. The top overall team in EPA, the Bucs, hit a four-year low for a side in the top spot. The average of the top ten hit a similar low. The team that finished tenth in the league (the Patriots) fell some way short of the team that finished tenth the year before (the Browns).

The middle class was fairly stable, but the top end of the league bottomed out. Defenses won the latest battle of the schematic trends. It’s over to the offensive side of the ball to find the next frontier.

Some of the top offensive minds were already preparing for the Beyond Times. I’ve talked ad nauseam about the different ways Kyle Shanahan, Sean McVay and Matt LaFleur looked to address the problem before it even became a problem, to differing degrees of success.

They each looked to different, broad solutions, though there was some crossover in the macro sense. One crucial change: an uptick in empty formations. Getting into five-wide sets allowed offenses to still overload portions of the field even with an extra man in coverage – it’s why teams across the league started to dabble with 4x1, quads formations. But consistently jumping into empty has its downsides. Obviously.

For one: you’re wholly reliant on your quarterback. Not every quarterback is good enough to carry the team on their back in empty. Some who are good enough to make all the throws aren’t the kind who can play point-guard from the pocket with five wide drive in and drive out. Plus, it puts extra pressure on the o-line, who don’t have the luxury of extra help.

As we head into 2022 and more defenses look to replicate the two-becomes-one model, non-Shanahan-McVay-inspired offenses will look for answers of their own – answers beyond sticking the quarterback in empty. Answers that allow an offense to have one concept flow into the other seamlessly, rather than the staccato mix of bouncing from their preferred wide-zone setup into empty formations.

So, what’s next?

How will offenses counter the counter?

The answer (maybe): The pistol.

The difficulty is pairing those traditional wide-zone and boot-action principles with the kind of shotgun-based, jump-to-empty attack that sides have settled on to try to ward off the new style of defense. The component parts of the run-game aren’t as effective out of the gun as they are run from under center.

The happy middle ground: the pistol. In the typical shotgun formation, the running back is offset. They sit in the sidecar, stood beside the quarterback. It changes things. Normally, the back will cross the face of the quarterback to gather the ball. This has its advantages: on play-action attempts, the quarterback can keep his vision downfield; it opens up an RPO world that’s all-but unavailable from under center.

But there are downsides. A run-game can be predictable, with the defense taking its cues from the placement of the back — cough *the Bengals* cough. The timing of the designs are specific and there’s a limited number of options from any given look from the offset gun, no matter how fancy the window dressing. Plus, the initial movement of the play is horizontal rather than forwards.

Some teams try to counter issues by embracing the same-side run. As noted, a back typically crosses the face of the quarterback on run designs from the offset gun. He meets the quarterback where he’s at, with the quarterback sliding the ball into his gut before the running back moves on to execute what’s ahead of him. Whether that’s inside-zone, outside-zone, counter, whatever, that initial snapshot is the same. Over time, a team develops tendencies. The same-side run is designed to break those.

As opposed to the running back meeting the quarterback, the roles are reversed. The back waits in the sidecar. The quarterback gathers the ball. The two do not meet at the mesh point. Instead, the quarterback takes the ball, shuffles to their side, and slams it into the chest of the back, similar to the ball-handling mechanics of a draw play — only hitting quickly at the snap.

It’s a nice change-up. It makes it tough for the defense to get a beat on the play design through the alignment of the back alone. The Chiefs have used same-side runs as a frequent tendency breaker throughout the Mahomes era to serve as an auxiliary to their zone-based run-game. More than that: it allows the run-game to attack different target points across the line of scrimmage rather than focusing primarily on the frontside B-Gap to C-Gap -- with a cutback lane tacked on. Widen the target area, and there’s more for the defense to cover. Force them to cover the width of the line of scrimmage, to spread their forces thinner, and there’s more of a chance of puncturing the defensive wall.

But the same side style has its restrictions. It helps break tendencies, but the rhythm and dynamics of the actions are different. Everything’s a little herky-jerky.

Add to that, running play-action off those initial actions is funky; the quarterback’s and running back’s feet are often close to colliding; it takes a lot of work to figure out the dance, work that could better be allocated elsewhere. Any turn-the-back play-fake is exaggerated, taking extra steps (extra beats), and doesn’t address the crucial issue: The quarterback is blind while the defense moves. Same side runs solve one problem, but they don’t solve the problem.

The pistol can help. For the uninitiated, the pistol takes the best of the under center and shotgun worlds and attempts to weld them together. The running back stands directly behind the quarterback in the shotgun, offering a similar pre-snap snapshot to a back being behind the QB under center.

You might remember Colin Kaepernick streaking through the Packers’ defense thanks to some pistol work, or Gary Kubiak and Peyton Manning marrying their two divergent styles during Manning’s final days in Denver.

The formation is naturally balanced – though some coaches like to use the offset gun to dictate the strongside of the defense. In the pistol, there is no concern about tipping plays through the back’s alignment. In fact, in the pistol, it’s the offense that gets to commission some reconnaissance. The team can take its back from behind the quarterback and shuffle him into one of the sidecar positions – left or right – prior to the snap to gather intel on the defense. Moving the back from a balanced look to an unbalanced look forces the defense to alter its front. It forces them to make a choice. To reveal vital intel that could pay off later in the game. To communicate – to possibly miscommunicate.

In the offset gun, a running back might flip from one side to the other to purposefully re-align the formation (or to get the back to a better spot for pass protection), but a team never walks the back back from the gun to the slot behind the quarterback.

That’s a small addendum. It’s the big picture stuff that is the reason teams will dust off the playbooks of circa 2015. Everyone dabbles with the look these days. It features somewhere in almost all playbooks. But as teams shift to an ever-increasing number of two-deep shells, pistol-as-base is likely to see a surge across the league.

If you, as an offense, want to force a defense out of those pesky two looks, you have to run the ball. If you want them to stay static, to drop an extra man in the box, you have to run the ball. You don’t have to run it at a dramatic clip, but you have to punish the defense when you do. And if that defense refuses to budge. If it refuses to spin a safety down or cram an extra defender in the box, you need to assemble a vertical offense – one that focuses on the run hitting downhill and flows organically into play-action shots.

Kubiak and Manning already figured this out. They were able to meld Manning’s spread passing concepts (condense-to-spread, tight splits, McVay-type stuff) with Kubiak’s wide-zone-based run scheme. They did so by moving to the pistol.

Why?

The pistol gets the back flowing downhill, not pressing laterally.

There is more diversity in the run-game – the back can go left or right (which sounds small but is crucial).

It’s easier for sides to run gap-scheme designs from an evened-out formation – from under center or the pistol – than with a lopsided shotgun formation – and there’s a larger wine list.

Everything hits a touch quicker.

Those quicker hitting designs look the same, rather than bouncing from a typical zone-from-the-gun run into a form of sprint-out play-action

The quarterback can be more creative with the fake, faking frontside or backside rather than being committed by the alignment of the back.

The defense stays in front of the quarterback.

Let’s start with that first point.

Running from the pistol is a downhill game. The runs strike vertically. In a world of two-deep safeties – moving or not – with defenses in purposeful light boxes, why string the run game out? Why wait and sift and bounce? Why delay things? Get up to the line, thump the ball down the hill, and move on. If a defense is going to purposefully lighten one area of the field or string itself out, good offenses will attack that as quickly as possible.

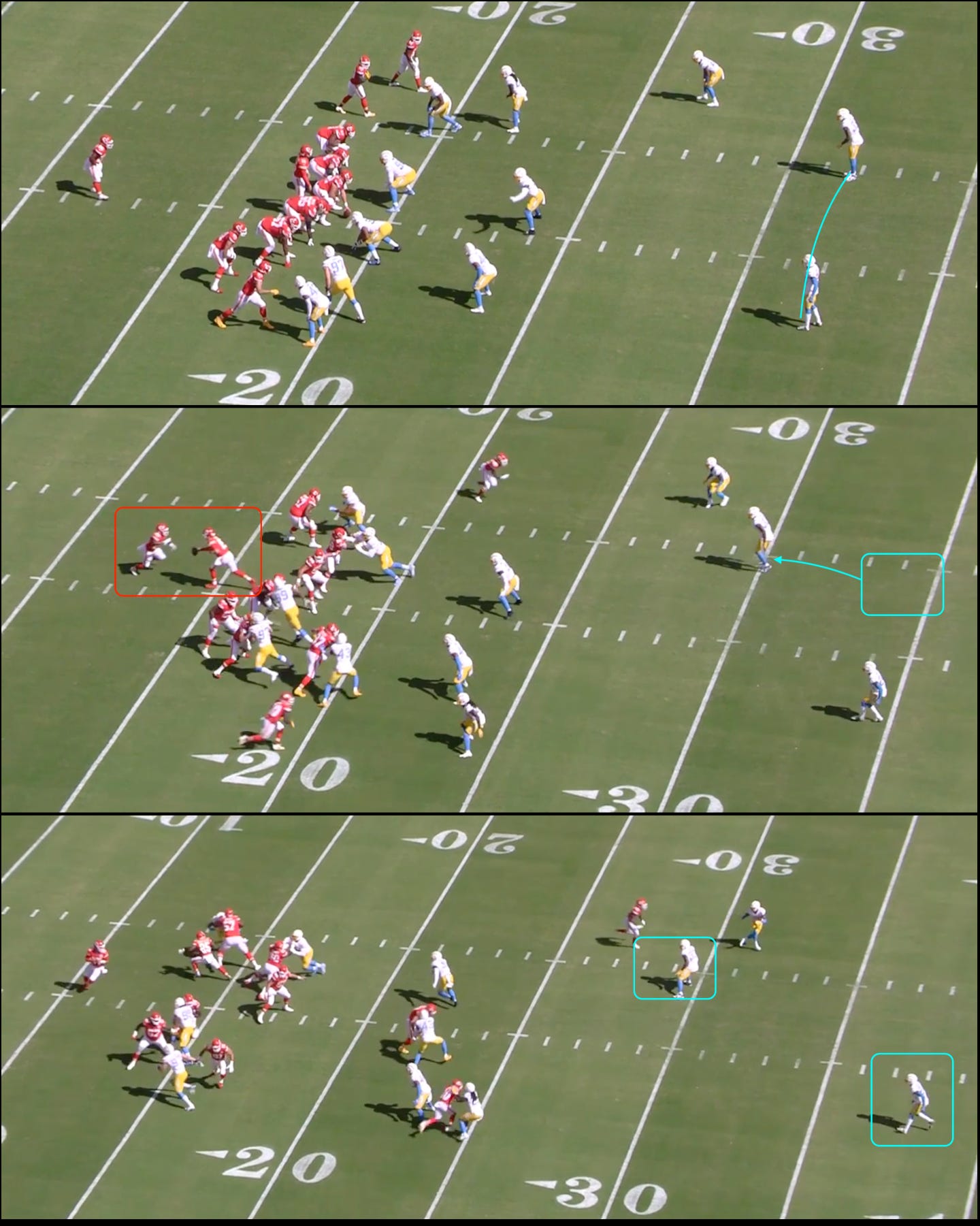

Just look at the path of these ball carriers, all running the same wide-zone/stretch design. One is from under center. The other, the pistol. The other, the offset gun.

Here’s a snapshot of the initial movements of all three:

Look at the target points. Look at the path. Can you distinguish between the bottom two?

For those struggling: The middle is the pistol; the bottom play was run from under center. Look at the verticality of the path of both compared to the top shot, where the running back must drive laterally, gather the ball across the quarterback, and then look to plant and fire upfield. The other two shots see the running back gather the ball while he’s rolling downhill. They’re trying to achieve the same thing. To read it out bend-bang-bounce. But the pathways are different because of the structure of the play design from under center (and in the pistol) to gathering the ball in the offset gun.

Against intentionally lightened boxes, do you want to move sideways at the snap or push the ball to where the defense is thin?

The benefit of the gun: The quarterback's vision remains downfield. There is a key distinction here between the final two designs, though: From the pistol, it’s a choice. A team can vary its quarterback’s vision on zone plays or boot-action attempts that flow from those looks.

From under center, they’re forced to turn their back to the defense. From the pistol, a side can bounce between the two styles – a forward-facing look on one snap; a turn-the-back variant on the next – from the same pre-snap shot and with the same design. The same play, two different feels. It doesn’t require shuffling from one formation to the other, which allows the defense to change their approach.

The brilliance of those Manning-Kubiak sides was how varied their run-game was – zone, gap, you name it, they ran it – from the same subset of formations, and all with quarterback movement flowing off them if needed (and Manning’s creaking legs could manage it). They didn’t tip anything through alignment. And if defenses presented a prior to the snap weakness, Manning was able to flip to the correct play without having to move his back, which would dictate a response from the defense.

Manning and Kubiak solved the riddle eight years ago. What’s old is new. Now, plug in Aaron Rodgers in place of a fossilized Manning. Or Matt Stafford. Or Trey Lance.

Teams in the college ranks have been shifting to a pistol-based approach in order to mirror some of the NFL’s turn-and-boot, deep-option concepts without having to go under center – which would require a ton of work. A bunch have even removed the ‘read’ element that was, at one point, considered essential when running the ball from the pistol – the concepts that powered Kaepernick and the 49ers and Robert Griffin III and Washington. College coaches realized that reading all the damn time was inessential. What was essential was to read some of the time, and to keep the rest looking the same, mirroring the effect without having to expose the quarterback in the run-game or relying on a quarterback to read it out correctly on-the-fly every time.

Ah, but if you can tack on the read element, you up the ante.

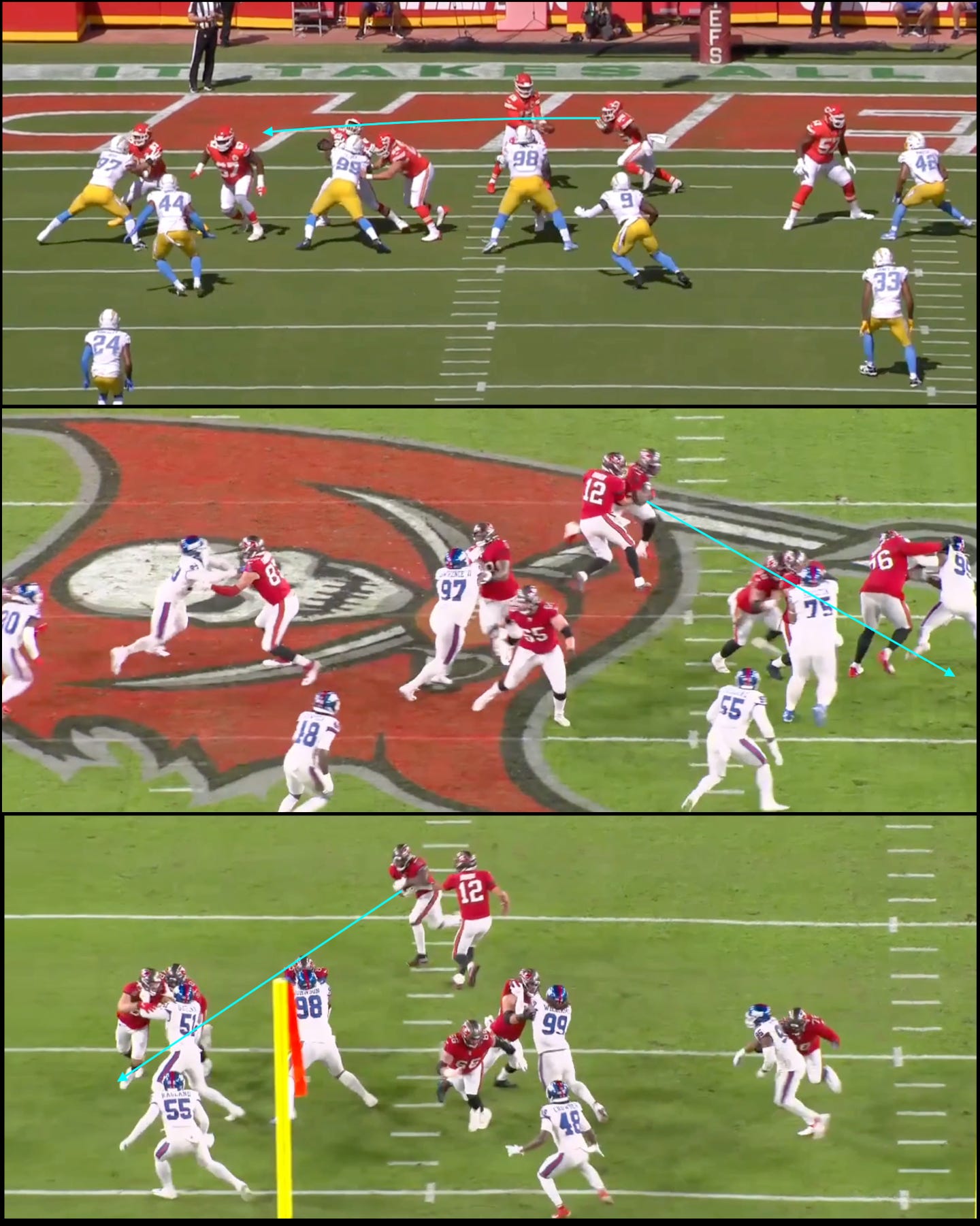

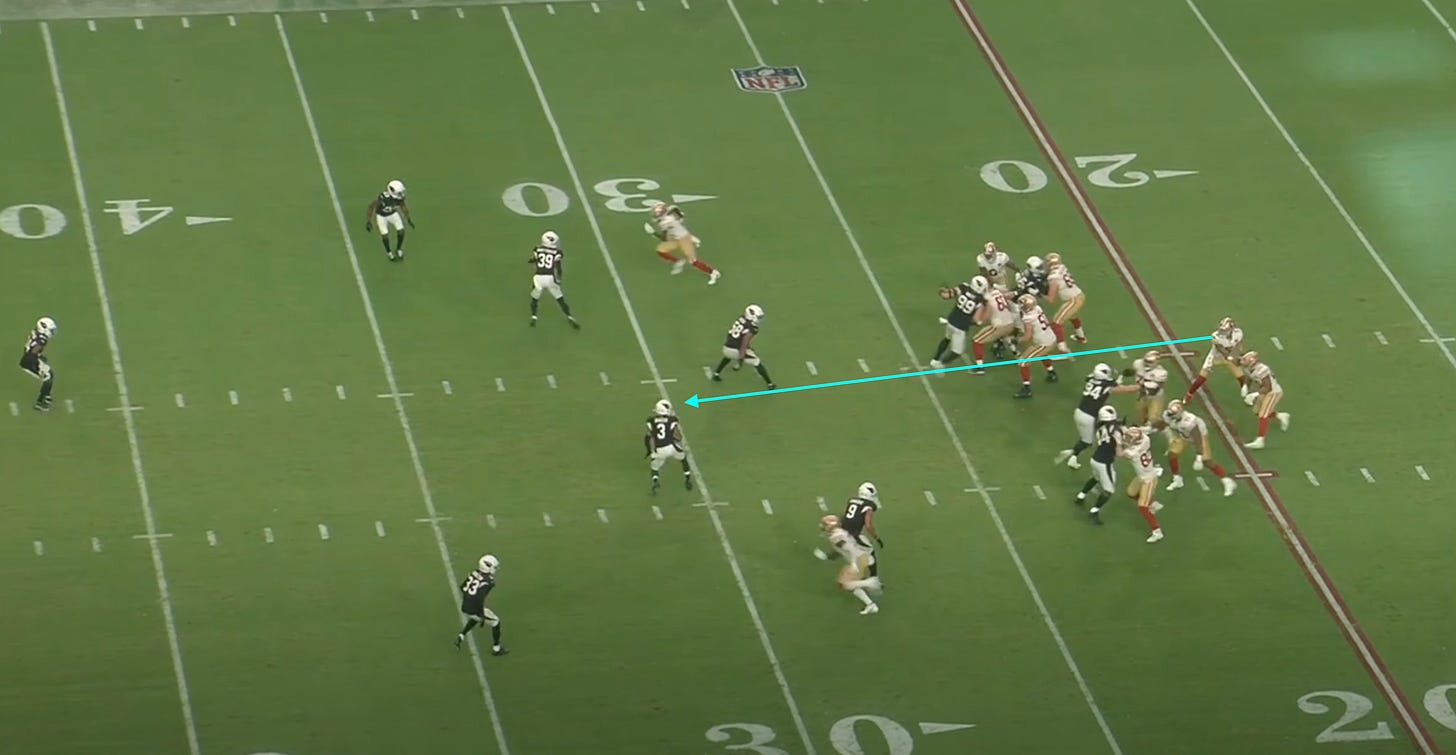

It only needs to be small doses. Lance’s first start for the Niners vs. the Cardinals signaled where Shanahan is likely to take his team in 2022. By jumping into the pistol and consistently reading the end man on the line of scrimmage, the Niners created havoc in the run game. Shanahan played a Greatest Hits of Greg Roman’s designs in Baltimore (which he created in San Francisco with Kaepernick). The results were immediate and dramatic:

Look at that! The threat of the quarterback run changes the dynamic, even if the quarterback isn’t pulling the ball. Shanahan did a crafty job throughout the game of muddying up the mesh-point. He disguised the quarterback-running back transfer. He used motion and movement to flash a player across the face of the quarterback at the snap to conceal the ball. It had a two-fold effect: Hiding the ball so that the Cardinals couldn’t track the initial path of the back; and set up play-action disguises for later in the game.

If that wasn’t dastardly enough, the Niners had a 6-4, 230lbs power-runner at quarterback who drew the bulk of the attention of the defense. Arizona was worried about Lance pulling the ball. It didn’t matter that they’d clubbed the Niners line for most of the day up front; they still panicked about what would happen if Lance tried to skirt around the edge. Re-watch the video above. Lance accounted for two defenders: Isaiah Simmons, lined up on the edge, sat down as the read man; Zach Hicks, playing off the ball, scrapped over the top in a bad to meet Lance at the point of attack.

Nope. There goes the back shooting out the other way, and a kick-out block wrapping around from the backside to mop up the end-man. That is pretty, pretty stuff.

But what really stood out was how Shanahan was able to get to all of his staple concepts without ever tipping his hand with the positioning of his back. The toss plays. The sweeps. Wide zone. All of his zone-based staples were there, from a fresh perspective.

Add those to a bundle with a series of quarterback options, an uptick in quarterback-power designs, general gap-scheme runs (counter, pin-pull, power), and some nifty hesitation blocks, and you’re no longer playing roulette. You’re playing blackjack. And your quarterback is a card counter.

How do you begin to try to solve that? The answer: You probably don’t. Just look at Lamar Jackson and the Ravens when their offense is healthy and humming. One of the only approaches: getting an extra body in the box. Then, hey presto, you’re back to facing all of those static, single-high defenses that Shanahan was put on Planet Earth to toast.

It’s all full circle, really. Shanahan first rose to prominence out from under the shadow of his pioneering father by building the ideal ecosystem for Robert Griffin III. He, too, paired the wide-zone base with a new flavor of option football based out of the pistol. That was only scratching the surface. What Greg Roman and Lamar Jackson have done since then has pushed the envelope on pistol-based football in the NFL – and Shanahan embraced a number of those designs with Lance in spot-starting duty last season.

But what Shanahan did do with RGIII which remains relevant to 2022 was neatly tie the run and the pass from the same looks.

Remember the start of this screed? If we’re worried about defenses morphing and moving while the quarterback is turned, what can we do? Keep the QBs eyes down the field! How can we do that while maintaining a vertical run presence? The pistol!

That’s one of two elements – but the most important. Hanging in the pistol allows the quarterback to maintain the threat of play-action, to stick the ball in the belly of a vertical runner, while also keeping their eyes downfield. Moving on the back-end? No problem. I spy a safety drifting into the robber spot.

It was notable in Lance’s first start how much of the play-action game Shanahan wanted to get to via looks that allowed Lance to keep his eyes fixed on the quarterback. When he switched it up in Week 17 vs. a hapless Texans’ side, Lance’s numbers popped, but his vision off play-action was poorer. He missed open shots. He ditched the reads of the system if he didn’t like his initial impression. By flipping that back to a PA-from-the-pistol setup, the young quarterback is able to keep his eyes clean, focused all the time on the movement of the safeties.

The Cardinals are one of the league’s most rotation-happy defenses. Lance was able to keep a clear vision of exactly who was rolling or moving and to where.

The Bucs and Tom Brady ran a similar style as the season drew to a close last year. They moved away from some of their quicker-hitting RPOs that Brady had previously run out of the pistol — similar to Manning — and instead moved towards taking play-action shots with his vision kept clean down the field as the defense moved on the back-end.

Weaponizing play-action from the pistol could be a game-changer for traditional dropback quarterbacks vs. moving defensive schemes.

After the initial boom and bluster of the Griffin-Kaepernick years, the pistol has rescinded from league-wide view. It’s hung around in spurts, used by specific coaches for specific solutions: Manning and Kubiak; Jackson and Roman.

The changing structures of defenses writ large will force different offenses to find different solutions, based on their personnel more so than a singular philosophical shift. But scheme work is more fashion than style. There will be an offensive trend or two – see: 4x1 formations – that ignites the imaginations of offensive architects across the league – a trend or two that all dabble with.

Moving to the pistol as a base formation is not a solve-all. Some coaches like to point out that it’s a balanced system that’s the jack of all trades and master of none. Better to lean into what you do best, which is typically a result of the skill-set of your players, than to seek balance for balance sake, the detractors like to point out. That’s valid.

So, too, is the fact that it’s harder to include the back in the passing game, which could be a no-no for a number of coaches who know they need to get five out in the route in 2022. Standing in the pistol makes it tougher on backs in protection. They don’t always have a defined job; there’s more scanning and it’s harder to scan because they’re planted behind the QB. And there isn’t the built-in leverage advantage that comes with being to one side of the quarterback, allowing a running back to beat an off-ball linebacker to the perimeter for the QB’s checkdown.

That is all true. But given the mini-evolution of defenses over the past 24 months, there are more answers to shifting towards a pistol-as-base offense than concerns.

As mentioned on a recent podcast with Doug Farrar, the Chiefs could solve a number of their broader issues – tying the run to the pass; running the ball more; diversifying their approach; ditching some of the zone-based RPOs – by upping their usage of the pistol.

But it won’t just be the Chiefs. Kyle Shanahan and the Niners have already committed to the shift. Aaron Rodgers has worn the pistol like a comfy blanket whenever he’s had a rough (by his standards) patch. With the team looking for a new-ish style with Davante Adams out the door, it could be welcomed back into the fold. The Titans are sure to incorporate some elements of their own if the day comes when they want/have to chuck Malik Willis on the field. The Ravens remain the pistol’s most ardent supporter, which is partly why I’m so high on the team heading into the season – they already have the built-in infrastructure to tackle what defenses want to throw at them.

No schematic tweak or switch is a fix-all. It’s about finding small, incremental wins. Last year, the game swung back towards the defense – the defense found those wins. Now it's over to the offenses to find answers. Reasonable minds can disagree on the best path forwards. Shifting the wide-zone-then-boot of it all from under center, the pistol is not the answer, but it’s an answer. An answer that can help unlock a wider approach that might just be the antidote to the league’s new style of defense.