Which Bill O’Brien did Bill Belichick hire?

O'Brien returned to New England this offseason, but was he brought back for a 2011 redux or to push the Patriots into the future?

Bill Belichick is a mad social scientist with a coaching whistle. Last season's experiment was a dud. Former defensive czar Matt Patricia was brought in to run the offense. Joe Judge, special teams whizz, was drafted in to coach the quarterbacks. An offense that had predominantly been based on gap scheme and north-south runs transitioned into a horizontal, one-cut-and-go, wide-zone-oriented group. At exactly the time that defenses were playing catch-up to the wide-zone rejuvenation and the chief architects of its rebirth had ditched the practice themselves in pursuit of the Belichick ideal of 2021, Belichick pushed the other way. It was weird. It was a failure.

In the career arc of the greatest to ever do it, it was an inexplicable oversight. Coaching is about more than having a binder full of plays. With Patricia at the helm of the offense, the culture and harmony was off from the off. “This is a joke,” was a common refrain heard echoing around the building after practices, sources told The Read Optional. The quarterback, skill position groups, offensive line, and defensive cohort all took digs. Mac Jones spent so much of the year shaking his head it’s a wonder it is still attached to his neck. A feisty competitor, Jones slipped from pushy to grumpy; coaches were pissed. “It was bleak,” an offensive assistant, who has since moved on, told The Read Optional this summer.

The move to a wide-zone-centered run game was part of a broader shift, a change in the overall operation of the offense. As own goals go, few have been more corrosive. The Pats averaged 3.3 yards per carry on wide-zone concepts, ranking 29th in the league, per Sports Info Solutions. They finished with a whine-inducing hit-at-the-line rate of 52.4%, a pathetic return for a side looking to redefine their ground game. They finished 31st in EPA on such concepts, ahead only of the Giants.

Switch that to gap-scheme runs, the bedrock of the run-game pre-Patricia, and things were radically different. The Pats averaged 5.3 yards per attempt on runs with a predefined end-point, the sixth-fattest mark in the league. They finished 15th in EPA per play, a middling return but significantly better than on their kick-and-go concepts. Gap scheme concepts were profitable; wide-zone concepts vaporized the offense.

The move to a different kind of offense made some sense, but it felt like the master was playing catch-up rather than forging a new path. The Patriots had a lot of the best practice stuff in their arsenal last year, they just too often ran it at the wrong time or were too sloppy in the details to be able to execute. They were completely overwhelmed versus good defenses. They looked slow.

All the little things that can be lost when discussing ideals and the big-picture stuff knee-capped a side with just enough fire-power to be league average group: spacing in the redzone, issues getting tight ends off the line, iffy blocking mechanics, busting rudimentary play designs.

Worse: Any sense of Mac Jones’ development was torpedoed. Jones looked insecure. He’d second-guess the play design at the top of his drop, even with receivers open and ready to be hit in-rhythm.

There is some Derek Carr-like ugliness to Jones’ game: the toes-y-ness, stopping his feet at the top of his drop, the heel clicks. All lead to inconsistency and inaccuracy, particularly the intermediate portion of the field.

As the season progressed, Jones got worse. Through the first half of the season, he ranked 19th in RBSDM’s EPA+CPOE composite, which measures the value of a play and how much the quarterback can be deemed responsible for the value. Teething pains, perhaps. Adjusting to the new system, maybe. Or not. In the second half of the season, as things disintegrated around him, Jones sank to 25th in the CPOE+EPA composite.

Belichick continues to insist the Patriots will persist with the changes – this was about restructuring The Patriot Way as opposed to a one-year whim. He kept things in the family, as he’s wont to do, turning to Bill O’Brien, architect of the Patriots’ league-warping 2011 offense.

It smacked of typical Belichick-ese, turning to a coaching retread he has a long-term relationship with. But the Bill O’Brien of yesteryear is not the Bill O’Brien of today. So did Belichick rekindle the relationship with O’Brien to revert back to a Brady era model — a tempo-based passing game featuring heavy personnel groupings married with spread principles — or does he want the new, updated O’Brien model, the post-Alabama O’Brien, the O’Brien 5.0?

O’Brien is charged with three things: Building a cohesive scheme that maximizes his young quarterback; elevating all the little things – the day-to-day coaching – that fell short and undercut the offense a year ago; re-establishing trust with a group still dealing with the hangover of 2022. O’Brien is known for the first two – not so much the latter. O’Brien’s shock-and-awe style of coaching will not be for everyone. It should mesh with Jones. He brings instant credibility, and has the teaching chops to dive into any aspect of his offensive philosophy with precision. Belichick did not move from a 100mph man to a zen-like philosophizer. He went from one asshole to another, only this one has the clout to earn buy-in from his players.

Patricia’s strange brew of braggadocio, inspiration and insecurity was never going to work for a team looking to refresh the main target point of its run-game, and the play-action shots that flow from it. Patricia is distant and cranky. O’Brien is an in-your-jersey crank.

Grumblings that Belichick wants to continue the trajectory of 2022 do not match up with league-wide trends, or the architect he’s installed to run things moving forward.

How the Patriots adapt to O’Brien ball – and how O’Brien adapts to his roster and the quarterback he inherits – looms as a pivot point for the AFC’s division of death.

When O’Brien strolled into his office in Tuscaloosa in 2021, he was greeted by something odd: A playbook.

Coaching at Alabama is different these days. With the constant churn of rosters and coaches and analysts and assistants and support staff at all levels, Saban chose to alter his philosophy. Brain drain is real and so, to offset the annual turnover, Saban set about building an organizing principle that would exist from staff to staff. Just as on the defensive side of the ball, where the guru of all that is right and good about modern defensive strategy, Saban no longer allows a coordinator to bring his ideals and principles to the building. It’s not the Mike Locksley way or the Bill O’Brien way. It’s the Alabama way.

Nowadays, Saban hands the Alabama playbook to his new offensive assistant. They’re allowed some input, sure. And they’re given autonomy over play-calling, though with Saban always listening in and ready and willing to change things when he so desires. Roughly 70% of the Alabama playbook is static — or, rather, it moves at Saban’s pace. New coordinators are allowed to install 30 or so percent of their own ideas or concept, and they’re given free rein to push the offense in whatever direction they so desire from the principles outlined within the ‘book. Want to be a 12-personnel-dense side? Call our 12 personnel stuff. Want to lead with empty sets? Take your pick from our fine selection of vintages, Mr. O’Brien.

Saban’s transition dates back to the days of Lane Kiffin, who installed a modern pace-and-space system and all of its option and RPO goodness. "It used to be that good defense beats good offense. Good defense doesn't beat good offense anymore,” Saban said in 2020. “It used to be, if you had a good defense, other people weren't going to score. I'm telling you, it ain't that way anymore." It was a philosophical transition that filtered throughout the program – the structure, recruiting tactics, practice habits, and the new specifics of the X’s & O’s.

Steve Sarkisian built on those principles in 2020. Beyond Kiffin’s foundation, Sarkisian instilled an ideal that continues today: wide receivers should never, ever be returning to the football, unless it’s an RPO design. Sarkisian (and Saban) knew they had the best athletes in the country. And so they didn’t want to concede ground to lesser players by forcing their receivers to catch the ball at a standstill. Concepts and routes were designed to allow receivers to always catch the ball on the move. They did. It worked. Points, trophies, national championships, Heisman trophies and a gaudy number of first-round picks followed.

Adding the RPOs and quarterback options was easy work. Every team from high school to college to the pros features some form of RPO (pre or post-snap), RSO, or quarterback option within their book. To amplify things, Saban, Kiffin, and Sarkisian embraced the deep-breaking options that first rediscovered popularity among the spread cohort of the Art Briles tree — and that Shaun McVay brought to the pros to club everyone over the head.

“Attack Daylight” became the mantra that filtered through every aspect of the offense. “Run to open space” isn’t the most profound of theories, but there is value in embracing the obvious. In college and then the NFL, it has proven revolutionary.

From the final days of the ground-and-pound era, where it felt like Saban could fall into the trap of being a dinosaur swimming against the spread-option revolution, Alabama moved to the vanguard of modern pro offense, using all the best practice spread-option work only with the finest players the country has to offer. They had a schematic and personnel advantage. Huzzah!

It remains the foundation of the ‘Bama book, and was at odds with the every-yard-is-impossible-to-muster pro mindset that O’Brien has had to deal with at every spot save for a stint as Penn State head coach. Rather than teaching (at least right away), he had some learning to do.

O’Brien has lived in the spread world before. At Penn State, he embraced the spread-option game. In the pros, he constructed an option-based system, at times, to help elevate Deshaun Watson. Wherever he’s been, he’s topped the charts in his usage of empty sets. But Alabama was a little different. This wasn’t one or two pieces of the puzzle. The spread-option and deep-breaking option world is the whole damn pie.

How much of The New will O’Brien pair with The Old in New England?

Mac Jones will be hoping for plenty. The early signs are encouraging. “The most interesting facet of O’Brien’s leadership? According to several people close to the situation, he has been implementing pieces of his system from the University of Alabama more than recycling Patriots playbooks of years past,” Jeff Howe reported in The Athletic.

It remains an oddity that Belichick – all-seeing, all-knowing – has staunchly refused to embrace RPOs with Jones. The Brady-backed Patriots were running RPOs before it was cool. Belichick was one of the first NFL coaches to truly nuzzle up to the spread in all its glory – doing so with O’Brien riding in the sidecar. But when Jones arrived from The Alabama Way, Belichick continued to press forward with the Brady-McDaniels version of the spread, all while ripping out the tempo (he was a young quarterback after all), before he set about tearing up large chunks of the classic Patriots style and trying to shapeshift the offense over the course of an offseason with a defense-first coach and special teams coach piloting the way.

Back in his Alabama days, Jones had two elite traits: Playing as the trigger man on RPOs; driving the ball down the field. He operated quickly, both on quick-hitting RPOs and in reading out the shape of the defense and the geometry of his receivers on those deep-breaking options.

The Patriots have installed precisely zero of those core concepts into their offense with Jones at the helm – beyond the rudimentary adjustments-vs-coverage that are featured in every side’s playbook.

In Jones’ time in New England, they have run precisely two (!) downfield RPOs. Even Patricia, who tried to add some optionality to the offense, preferred the bubble-screen tag variety rather than the downfield basics, typically to put a backside stretch on the defense away from the targeted run side. It was an addendum, a break glass option, something to boost the potency of the run game, not to feature Jones as a downfield bomber.

Any notion that NFL teams are ‘limited’ in what they can do down the field on RPOs because of the differing rules from college to the pros has been disproven by Sark in Atlanta, the Eagles of Steichen and Hurts, the Chiefs of Reid and Mahomes, and others. There are limitations, and vertical RPOs are more of a layering device for an NFL offense than they are the kill-shot that they are in the college ranks, but they’re still a core element of any well-rounded pro offense.

Jones isn’t just comfortable in the read-and-fire world. He thrives. Jones operating in a point guard role is Jones at his best. Jones finished with the highest passer rating and on-target percentage among any quarterback in the Power Five during his last year in school. He led all Power Five QBs in EPA/play:

Jones finished with an eye-watering 27.6% explosive play rate on 87 RPO dropbacks. He racked up 10.6 yards per attempt and 10 touchdowns with no interceptions.

And these weren’t basic dump-offs to a marauding Devonta Smith – okay, some were simple flips to a marauding Devonta Smith. These were intricate designs designed to drive the ball down the field off an option read – often paired with deeper breaking options or pre-snap reads for the receivers.

Alabama paired a post-snap quarterback read – typically a second or third-level read – with as many as eleven (!!!) options: the running back handoff; a quarterback keeper; a horizontal screen to place a perimeter stretch of the defense; two or three-way goes for receivers to ‘attack daylight’ as they saw fit based on the coverage shell.

Jones feasted. He could generate a ton of torque to anywhere on the field without having to adjust his feet – his slingshot, hip-forward delivery is what had so many teams intrigued in the draft. Alabama could call the same play for an entire series with widely varying route distributions.

Running that with Alabama’s supporting cast is easier than not, but it is not easy. And isn’t the whole point of coaching to make things easier where possible, to maximize your players’ strengths and put them in the best spot to succeed?

That’s all the more important when you’re operating with a quarterback who is no off-script savant and must play within the flow of the offense rather than generating offense by himself. The Patriots, thus far, have run the other way when it comes to their third-year QB, pushing towards a style that has eliminated a trait that made him a success in the first place.

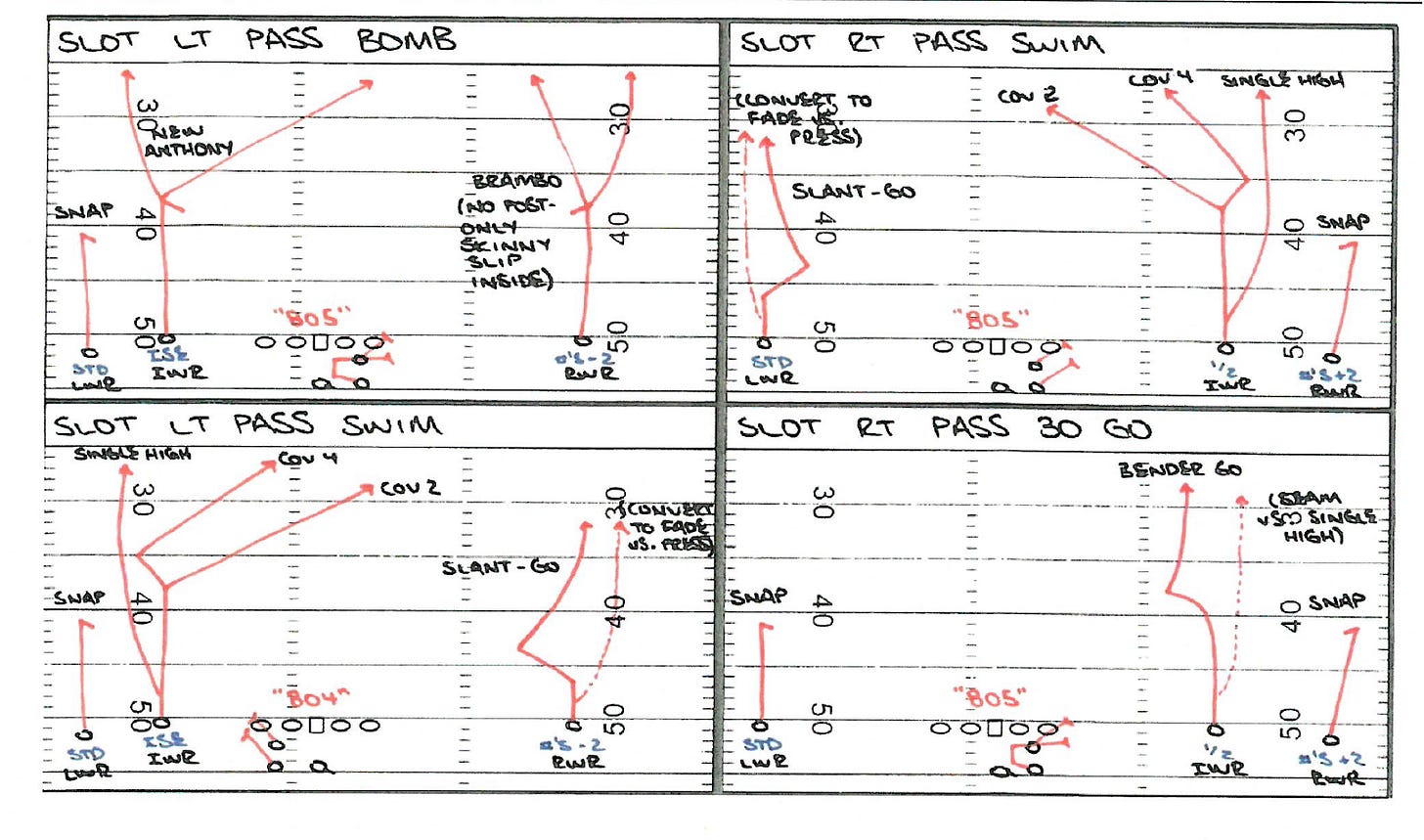

O’Brien arrives with a new-found set of concepts Jones has already mastered. At Alabama, the coach indulged in the Kiffin-Sark model. He delighted in the strain vertical RPOs could put on a defense to amplify Bryce Young and aid the run game:

He used access RPOs, simple pick-and-flick-it strands based on the depth and leverage of a single defender. If they give you access to a portion of the field, you best go ahead and take it.

He understood the raw mechanics beyond the theory, leaning into pistol sets that could disguise the path of the running back-quarterback exchange (and the target point for the back) while also keeping the quarterback’s arm angle clean, allowing Bryce Young to drop his arm to get creative working around defenders.

That can seem like small stuff, like a given. It’s not. Those are the little things that can make an offense sing – the little details that were missing in New England last season beyond the big picture stuff. It was O’Brien’s latest addition to the Alabama Way. Previously, Kiffin and Sarkisian had preferred same-side run designs to work as a counter to their own tendencies. The Pistol builds in natural tendency breakers while also cleaning up some of the sludgy arm and footwork that can come with some RPOs based on the position of the back and the QB-RB exchange.

RPOs under O’Brien weren’t quite as effective as in the glory days of Kiffin and Sark, but that had little to do with the specifics of the X’s & O’s and more so to do with personnel on offense – quarterback aside.

O’Brien showed he got it, and would champion the cause. Ditto for those deep-breaking options, which still form the foundation of Alabama’s passing game. Three-way goes from the slot and coverage adjustments have long-formed part of O’Brien’s attack, and were at their most effective in New England with Brady et al. but working at Alabama pushed O’Brien into adopting even more sophisticated and devious tactics.

They’re the same concepts Jones punished defenses with while in school.

Making those reads in real-time is football’s highest art. It requires a second-by-second mapping of 21 other humans in motion – and the brainpower to think one step ahead of them. Oh, and to do so while in sync with your receiving corps, and hoping they don’t chase the same patch of grass – and adjusting if they do.

Whatever ‘it’ is, Jones has it. O’Brien will have to figure out if he has the receiving corps to match. The mechanics and rhythm of deep-breaking options are tricky to teach and tough for some players to internalize. Not all players can navigate the gray, they prefer the exact timetable of an A-to-B route. In college, one or two options can bust so long as someone finds space. It doesn’t work like that in the pros. But if the goal is to emphasize what Jones does right and minimize where he struggles, then…

Jones remains a talented deep-ball thrower, though has often lacked the tools around him – both the players and the scheme – to be able to take advantage. He shows great touch down the field. Last season, as things came unstuck, as he lapsed into dumb turnovers and fretful decisions vs. the blitz, he continued to make headway when bombing away, without putting the ball in harm’s way. Jones finished with a 2.8% turnover-worthy play rate on 15.2% of his dropbacks last season, per PFF. That’s a volume-to-TWP rate matched only by those who were allergic to the deep ball in 2022… and Jalen Hurts, who ascended from a talented deep thrower to a demi-God last year. Hurts finished with a 2.5% TWP rate on deep shots, with a 20-plus yard throw subsuming some 13% of his dropbacks. Deep shots made up 15.2% (!) of Jones’ dropbacks last season, the fifth-fattest mark among all eligible QBs.

He threw with decisiveness and precision down the field, both lacking when working to other areas.

Finding ways to continue to unlock Jones as a deep-shot artist will sit at the top of O’Brien’s to-do list. Pampering the quarterback with vertical RPOs and deep-breaking options will help spring easy completions and explosives, both hard to come by last season. But O’Brien will default to his favorite answer of all: Get to empty.

There is no stronger evangelist for empty sets than O’Brien. The Empty Theory, as it’s dubbed, is about getting the offense into a form of matchup ball. Regardless of personnel or formation, the quarterback is able to survey the field pre-snap and identify a one-on-one matchup that he likes.

There are a whole host of benefits to jumping into empty:

The defense is typically static at the snap

It limits how much a defense can move and rotate on the back end

Defenses typically default to a coverage tendency, particularly if an offense motions or shifts to empty, something an advanced staff can scout – it’s usually straight man-coverage or some form of match-quarters coverage.

It reduces the kind of blitz and pressure paths a defense can run

An offense can swamp or overload two-deep coverages early in the rep

All five eligibles can get out in the pattern quickly

It allows the offense to stretch the field horizontally with clean spacing

The main downsides: there is no hiding place for the quarterback; unless you have a mobile quarterback, there are none of the benefits of play-action.

Empty sets are on the rise across all of football as coaches look to use mobile quarterbacks (most notably Jalen Hurts and the Eagles) to hammer teams with the QB-run from empty before taking advantage in the dropback game.

No coach preaches the gospel of empty sets and ‘match up’ football more effusively than Bill O’Brien. Spreading the field pre-snap and hunting one-on-one shots rather than bothering with the intricacies of play design is at the heart of all things O’Brien-ism. 15 percent of Bryce Young’s dropbacks under O’Brien at Alabama came in empty, with the coach pairing his vintage concepts with some of Alabama’s new-fangled deep-breaking option designs.

Jones has proven to be a capable operator from empty when given the chance. He finished 23rd in EPA per play among eligible quarterbacks last season, but the underlying figures were strong. He ranked third in pressure rate, ninth in sack rate, second in adjusted net yards per attempt, fifth in on-target rate, and finished with a 125.6 quarterback rating, good for second in the league.

Again, the design of the offense was lacking. Patricia and Co. used empty sets to help march the ball down the field, as part of a quick-rhythm attack. O’Brien uses empty sets to get to everything, including getting the ball vertical — in a hurry.

O’Brien delights in pairing empty sets with tempo, a style that bamboozled opponents during his first go-around with the Patriots. It’s here that O’Brien’s marriage of what he does best with The Alabama Way was at its strongest: the coach was able to get into and stay in empty without needing to huddle because he could call only a handful of plays that, due to all the optionality of the routes, could unfurl as if 20 individual designs. On one drive against LSU last season, O’Brien’s Alabama ran eight consecutive plays from empty without huddling.

Tempo all-but evaporated from the Patriots' offense last season. They ran only 37 snaps in the no-huddle last season on dropbacks when trailing or leading by a score, but were the fourth-most effective offense in such situations in the league. Only in desperation mode did they truly begin to ramp up the pace of things, running half the number of no-huddle snaps as the likes of the Bills, Giants, and Bucs, who crushed sides with tempo-centric attacks in even-ish game states. There’s a lot of meat left on that bone.

Tempo isn’t exclusively about going fast. It’s about modulating things, keeping defenses guessing. When the Brady-O’Brien offense was really, really rolling, they majored in catching defenses in compromised personnel groupings or situations and rattling through the gears before the defense could correct problems. They would increase the tempo of their play and the play-calling. Once they knew they had a defense in the grouping they wanted, they’d rattle through a double act: a quick-hitting strike, a race to the line, and then hit their shot play.

It was the same at Alabama, though rather than requiring the quarterback to call another player or orchestrate proceedings from the line of scrimmage, he could simply dial up the same play and bank on one of those deeper breaking options to find space. O’Brien has a strong in-game antenna. He will pick on weak spots until they gush blood.

Getting into empty can help innoculate Jones from his aversion to the blitz, too. Jones was one of the worst quarterbacks in football last year versus extra pressure.

Beating the blitz isn’t difficult for good quarterbacks. When the opposition sends an extra defender, that leaves a receiver open – or it means single coverage across the board. Defenses rarely blitz the best of the best because they understand the likes of Burrow, Prescott, and Mahomes can decode and find an open target easily.

There were structural issues that dinged the quarterback last season – obvious tendencies; blitzes vs. specific looks that gave him little to no shot; a struggling offensive line; receivers unable to separate early in the route – but Jones should take the brunt of the blame.

That is unacceptable from a professional quarterback. The Bengals (Loudini!) walk one defensive back down to the end of the line of scrimmage to create a late five-man wall, with the DB lined up across from an attached tight end. They tagged that with a slot blitz. It was a wicked design, one that put the Patriots’ running back in a two-man bind. But the sack was on Jones. He altered the protection away from the late lurker, but engaged in a passive play-fake rather than scanning to confirm the roaming DB was indeed in man-coverage. He never scanned for the slot blitzer. Replacing the blitzer – chucking the ball behind the blitzers head – is the most elementary of quarterback tactics.

Getting into empty sets limits a defense’s blitz/zone-pressure portfolio. Moving to an empty-heavy style will shift some of the identification burden from Jones and offer him easier outs when defenses do send pressure.

It’s a balancing act. Last year’s Pats team failed to find a symbiosis between its ground attack and Jones operating as a point-and-shoot thrower from the gun. The run game suffered on plays based out of the gun – and they struggled to sell play-action actions as well. The Patriots finished 32nd in EPA per play on runs from the gun last season, a figure that bounced to 19th when the run game operated from under center.

Playing from the gun is Jones’ natural habitat. He looks more comfortable, though found success last season on deep play-action shots when working from under center. He isn’t a natural boot-action quarterback, and struggled to adapt to the changing contours of defenses once he’d turned his back to the field.

Sliding Jones into more of an empty/RPO-heavy system will ding the run-game. Everything is a trade-off. On balance, promoting the strengths of your quarterback over the steadiness of a run game is a deal worth making.

Finding a balance between Jones’ preferred space and what works best is what coaching and play-sequencing is all about. There are ways for O’Brien to scheme more easy wins, to keep the offense advancing, while not curtailing some of the best practice under center work that was such a success for the team last year – both in the passing game and denting the defense with the run. Hitting on the correct alchemy will be different opponent-to-opponent, but both must form the foundation of a modern ‘pro’ offense – and O’Brien and Jones, given their particular circumstances and skills, should be at the forefront of the latest movement.

Adjustments flow in both directions. Jones will have to continue to evolve his game, but it’s incumbent on the organization to put their quarterback in spots where he can thrive. Planting him in a wide-zone-then-boot style offense was tantamount to asking a labrador to make an old fashioned.

The pressure has been amped up on Jones. Belichick was, umm, less than bullish about his quarterback over the span of the offseason, though the Patriots steadfastly refused to get involved in this year’s quarterback carousel. He will enter the season as the team’s starter with a coach and play-caller who has spent a couple of years at a Modern Offense finishing school.

If anyone can find a way to balance the New England way of old with Alabama’s football of the future, it should be O’Brien.

The margins between a disastrous offense and a passable offense are slim. Bill O’Brien’s job is to keep the Patriots’ offense afloat so that the team’s all-world defense can close out close wins. There are merits in trying to re-run the style of 2011. That’s, probably, Belichick in his comfort zone: marrying some of the old with the new. But to give both O’Brien and Jones the best opportunity to succeed, embracing the deep-breaking option, RPO-heavy, run-the-offense-from-empty style that O’Brien piloted at Alabama is Belichick’s best bet.

Great read Ollie! Asking a labrador to make an Old Fashioned is hilarious!!

I noticed the Giants came up (somewhat randomly) in a couple of places - not sure if you dug that deep in, but I'd love to read something on what the Daboll-Kafka thing was/is, where it's going. I don't think I've seen any good in-depth analysis of that one. Cheers!