Who do the Titans want to be?

Benching Malik Willis makes sense in the short-term. But who do the Titans want to be on offense in the long-term?

Perhaps no team faces a more interesting couple of months than the Titans. They could be division champions again next week. They could miss the playoffs. Ryan Tannehill is on IR; Joshua Dobbs is starting; the face of their franchise is battling an injury, and facing whispers that it's all coming to an end soon; the architect of their recent division-winning run, Mike Vrabel, is at a crossroads.

A culture war? Too hyperbolic. A crisis of faith? Too sophomoric. Confusion? Maybe too angsty. But there’s a fascinating dilemma bubbling below the surface in Tennessee: who, exactly, do the Titans want to be in Week 18 and beyond?

We’re talking offense here. The Titans turned the reins over to Malik Willis after Ryan Tannehill sustained an injury, only to bench the rookie ahead of Thursday night’s game vs. the Cowboys in favor of Dobbs, a player who joined eight days before and had never started a pro game. It felt like a more consequential decision than that of a rookie being in over his head: The Titans can get out of Tannehill’s contract pain-free this offseason, and given the state of the current roster and the pain of the last 12 months (another playoff exit; trading AJ Brown; issues along the offensive line; firing Jon Robinson; Henry aging) now feels like the right time for Titans to move on, to look for something new.

That, in the abstract, makes sense. It’s the right thing to do. But to move on to what, exactly? Not the player. You can debate the specifics of Willis versus Jimmy Garoppolo versus Derek Carr versus Intriguing Draft Prospect X. But to what style of quarterback — and what style of offense?

Sitting Willis for the short (and long) term was the correct decision. He was always going to be a long-term developmental prospect. But even developmental guys have to show something – some degree of core competency – sixteen weeks into their rookie season. If you cannot line up and execute the base offense by the end of your rookie season, you’re in trouble.

Willis’ playing time has been fractured this season. He came in and out of the lineup whenever Tannehill was hurt, and so wasn’t given five sustained weeks to learn and grow while the bullets were flying. But what we have seen has been (almost) a representative sample for a rookie… and it’s made grim viewing. It’s been 200-plus snaps of manic quarterback play.

Tennessee’s development plan with Willis was interesting from the off. Rather than race to the RPO, option-based world that Willis majored in at Liberty, they told him to get with the times, kid. They placed tight restrictions on his use of his legs in preseason and throughout practice. They wanted him to spend year one figuring out some of the nuances of the game: operating the game from the line; playing on time and in rhythm; the repetition of his footwork and his release; tying his footwork to his eyes; mastering full-field reads and a multi-progression passing game. Embracing the complexities of pro football early rather than riding the RPO/option train early on and trying to figure that stuff out in year three or four was the plan.

The end goal, one assumes, would be to drop Willis into an augmented version of the Titans’ traditional wide-zone-then-boot system, one heavy on turn-the-back play-action and deep-breaking options that rely on the timing, footwork, and anticipation (which is tied to the other two component parts) of the quarterback. Fail within that structure, and Willis would have the athleticism and arm talent to take off and create magic on his own. Blend that with the RPO elements and pace-and-space football that are innate to Willis’ game and you start to encroach on Eagles’ territory, which is something approaching schematic nirvana.

The Titans, it seems, purposefully eschewed embracing a Lamar Jackson, option-centric offense, which comes with its own constraints. Nor did they want to drop Willis into some Rodgers-LaFleur-style multi-progression system. Instead, they tried to fuse together the best of both worlds — the core of the offense being largely the same with some sprinklings of the option elements that could take advantage of Willis’ A-plus athleticism.

For any rookie, picking up on all of the pre and post-snap intricacies is a huge ask. For Willis, coming from one of the most RPO-dense, progressions-are-meaningless, see-it-throw-it offenses in college, it must be mind-spinning.

And it’s been chaos. From the pre-snap operation (getting the motions and shifts in on time) to the at-the-snap operation (Willis and company were constantly bungling the snap count; one side of the line was often on the move before the other realizes the ball has been snapped), to the post-snap operation (full-field reads; deep-breaking options), you can see the cogs turning. You could almost feel the discomfort leaking through this screen. This is all a little too much. It’s happening too fast. Do you ever get a play off? Can I just drop back and rip it?

On one snap, Willis might nail the pre-snap sophistication, only to lose any sense of time and place and concept at the snap. On others, the pre-snap operation was a mess, only for Willis to deliver his most synced-up strike of the drive.

The Titans persisted. When Willis was chucked in mid-game or on short notice, there was an uptick in the option stuff. But with a full week of practice, the Titans reverted back to the halfway house version of their offense. Against Houston, they embraced the traditional, Henry-backed, power-running-from-under-center approach before toggling to more of the spread-option elements that sit as comfort food for a young quarterback that was struggling.

It made sense: the hallmark of the Titans' offense is giving the ball to Derrick Henry and getting out of the way. And it’s an approach that continues to work, even as Henry begins to slow down by his own lofty standards. Yet pairing Henry’s style as a downhill thumper with Willis’ natural tendency to want to play a spread-from-the-gun, spray-it-to-the-perimeter style of football is tough. Willis was – and remains – a chuck-then-dump style of quarterback: He wants to drive it deep down the field or get it out to the perimeter on some kind of bubble, smoke or quick-hitting route. Blending that with the concepts the Titans run from under center, where Henry is most potent, is tricky.

Henry doesn’t want to run from the gun. He doesn’t want to sit and ride out a mesh-point, unsure if he’s getting the ball or not. He doesn’t want to plant and move laterally before deciding to make a cut or not. He doesn’t want any extra beats in the design. Derrick Henry wants to get downhill. And he wants to get downhill now.

Tennessee hasn’t changed its offense for years. Their staples are staples because they work. Duo. Wide-zone. Split-flow inside zone. Counter. Toss. All from under center. All with Henry driving downhill at the snap. Rinse, repeat.

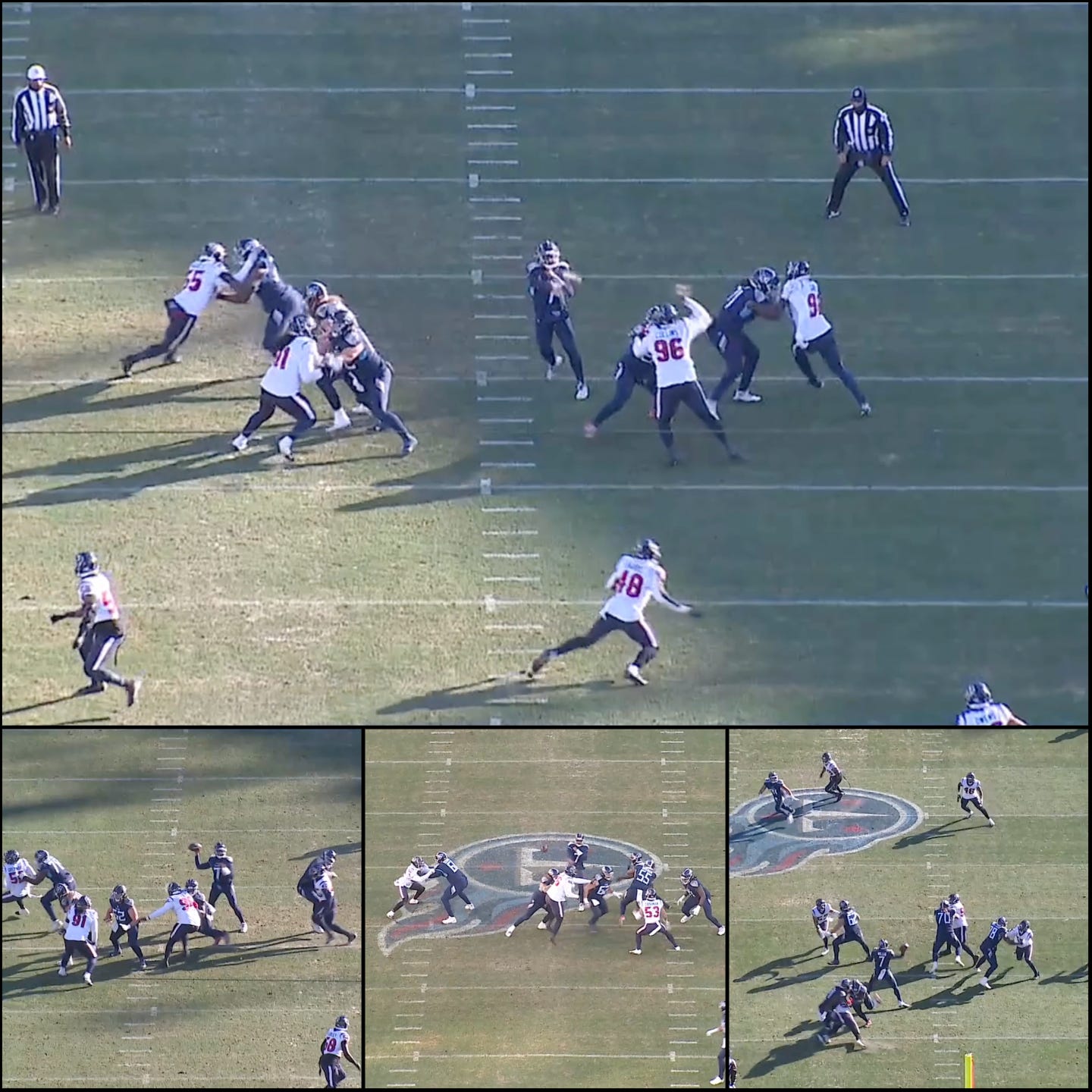

Switching that up to suit Willis made things awkward. Adding in an option element, in theory, should make a back more lethal. Optioning someone on the defense takes an extra hat out of the play – or freezes the most troublesome defender. And it was effective in spurts. Tennessee’s two scores against Houston both came on option designs with linemen pulling and moving, the kind of run-game creativity unavailable with Tannehill or a more traditional turn-read-fire quarterback under center:

Look at that thing. It’s a beauty. It’s a counter option. Nothing overly fancy. Willis’ read froze the backside defender, gifting the left tackle the time needed to peel around. The Titans were able to pull their backside tackle and guard, both slicing across the formation – one to kick out the end man on the line of scrimmage; the other rolling up to clean out a linebacker. Henry wiggled up to the second-level untouched. From there, it’s a wrap. Just the threat of Willis pulling the ball helped Henry to climb unchallenged. Add a tick to the plus column.

Tennesse’s second score came via the same play, this time with Willis pulling the ball and taking off before being thrown into the end zone by his own lineman:

But switching from one style to the other as the base of the attack is about personal preferences and trade-offs. Outside of those explosives, the option elements were duds. Moving from an under-center attack to a zone-from-the-gun would change the running style for Henry – effectively making the Titans' most effective player less effective – and trade in turn-the-back play-action shots for flash-fakes, which is where Willis is more comfortable but is less effective and less conducive to explosive pass plays. The whole point of selecting a Willis – a big-armed, athletic quarterback – would be to add more variance and explosivity to an offense, not to trade out play-action shots for flash-fake-and-go, push-the-ball-to-space efficiency. Too often, toggling to the from-the-gun, RPO/option package meant taking Henry off the field.

That trade-off wasn’t worth it, not when Willis looked so frazzled in the passing game. Dropping in Dobbs ahead of the Jags game next week was about not only the orchestration of the offense but the reliability that the quarterback will hit the right marks and make the right reads in an offense conducive to the style of running game that maximizes Tennessee’s best player.

And that’s the big issue here. The Titans tried to wed two contrasting styles with Willis and Henry, and the rookie was too far away for any knock to Henry’s game to be worth it. To do anything in the playoffs, Vrabel likely felt he had to lean one way or the other: To fully embrace the spread-option world or to ride with what his running back does best.

Can the Titans ever find that middle ground? Or will they be forced into picking from somewhere along the extremes? Do they even want to anymore?

The answer is murky. Quarterback development is not linear. But the early returns have not been good.

Willis has been a mess in the passing game. There have been the briefest of sparkles, the odd time when Willlis’ feet, eyes, and slinky release align, the kind of plays that make you take an extra wiggle in your seat, that brings a glint to your eye. Possibilities:

But they were few and far between. Willis’ best work has come from scrambling around and making plays, a no-no to the Titans brain-trust who have been mercilessly pounding the drum that Willis needs to stay on schedule to have any shot to play in the medium-term.

Footwork has been the biggest issue. A quarterback ‘marrying his eyes to his feet’ is one of those scouting cliches that’s easy to dunk on. It sounds like bullshit; like someone spouting jargon to try to seem smart. But it’s real. Willis has often looked confused about where he’s going with the ball, and therefore how his feet and body should align.

To marry the eyes to the feet simply means to ensure to the quarterback is lined up to the target, with a settled, stable base, ready to deliver the ball with accuracy and velocity when his eyes tell him it’s go-time.

Willis is rarely, if ever, lined up to his target, even when he gets the ball to where it needs to be.

As noted on a recent Home & Home podcast with Jon Ledyard, some young quarterbacks fall guilty of the load-and-wait idea. They line up to fire. They cock and load. And they wait… and wait… and wait. The movement patterns are learned — they don’t yet flow naturally. And as those quarterbacks wait, they patter their feet. Some are able to maintain a balanced base, allowing them to generate power from the floor, to move into the throw and to deliver with accuracy and velocity. Kenny Pickett is a good example. He used to play with antsy feet, his footwork often falling apart as the game quickened up. Now he plays with fast feet. But they’re light feet. And he’s stable. He’s ready to deliver (most notably in the quick game) whenever needed. There’s minimal heel click; he doesn’t rise on his toes (which often leads the ball to sail); he stays aligned with his target.

Pickett is playing fast, but not frenetically. He plays with a bounce and a rhythm. There’s a smoothness to what he’s doing; his feet flow organically with his eyes and where he wants to go with the ball.

Other young pups start to panic or lose their mechanics. Some start to get really heel-clicky or climb on their toes. They narrow their base, drawing one foot to the other. If pushed to get the ball off — because the route concept has developed or they feel pressure — they’re forced to either reset their feet (adding extra time to the throw or throwing off the rhythm of the play) or to deliver from an unstable base, leading to inaccurate throws.

Some (Desmond Ridder, for instance) start to elongate their base as they pat and wait, knowing that they should keep their feet under them. But they slowly — ever so slowly — widen their feet so that they’re no longer in a sturdy enough position to really drive the ball, instead delivering from their back foot or from a funky, overextended base or needing to regather their feet before letting the ball go.

Willis mostly falls into the former camp – though he dabbles with all of the above. He has choppy, antsy feet — and that might be this writer being kind. There is little rhythm or bounce to his footwork. He plays on his toes. His timing is choppy. There are stutters. Everything looks uncomfortable.

His base is too often unstable – he gets too narrow, taps his feet and overextends himself. He falls off throws, forcing him to lose accuracy and velocity, and disrupting the timing of the passing game.

There is not one issue there. All phases of the process are broken. That compilation, frankly, is not professional football. The earlier flip-book showcases the issues: the initial drop, the top of the drop, the gather, the base. None of it is in-sync or replicable. And professional football is all about repetition, about repeating the timing and footwork of a concept so frequently that it seeps into the cellular structure of the quarterback.

Fixing that is no small thing. not small fixes. The Mahomesification of the league might have convinced some that the old rules (the timing of the drop to the depth of the route; having all your cleats in the ground on release; being all the way lined up to the target) is not essential or less important. But run through any game of Mahomes, Allen, Herbert, or whoever. They play with plenty of rhythm and timing. Their core mechanics are excellent. What elevates them from great players to aliens is their ability to do both. They play with ideal mechanics on plays where they’re allowed and then can break out of the structure and produce from funky angles and cooky platforms when the game demands it.

You cannot build a competent passing game around that. Willis has not completed a throw beyond 20 yards in his 53 dropbacks this season; he has completed only three throws over ten yards; he has not completed a throw over ten yards in the middle of the field. And that is not due to a lack of arm talent or the creativity of his arm angles or his ability to levitate and deliver with two feet in the air as a Rodgers-esque rotational thrower. It’s because his basic mechanics are a mess.

Rebuilding a quarterback’s throwing mechanics takes time and reps. Time and reps that NFL staffs no longer have. There is no longer time for a quarterback coach, passing game coordinator, or OC to spend countless hours repping out footwork.

The work of altering a throwing motion is not work conducted in-season. It’s for the offseason. It’s for the private, biomechanical experts who help the player do the heavy lifting away from the team facility: Jalen Hurts redefined his throwing base pre-draft; Brock Purdy changed his body composition to become a less toe-led thrower thanks to his throwing expert. Those (effective) changes had little to do with the NFL staffs those quarterbacks play for — staffs who simply reap the benefit of the player's hard work and dedication and then look to match up their system and its timing with their quarterback's mechanics.

Willis will need a full offseason-plus to start rebuilding his release from the ground up.

The choice for Vrabel became clear ahead of Thursday night and what is tantamount to a playoff game in Week 18 vs. the Jags: To try to let Willis work through the growing pains in the hope the extra reps will help for next season and beyond; or to lean all-the-way into a Tebow-style, run-only, gimmick offense that would be built around option-runs from the gun, which would ding Henry.

What comes next?

Even the most cynical RPO guru or Willis believer (Willbiever?) would view Tennessee’s split-flow-Duo-Toss package as inviting and comforting as slipping half-drunk into a warm bath. When you have the game's top tailback, it’s best to hand it to him with a head of steam rolling downhill.

But for how long can the Titans sustain that diet?

Last season felt like the pivot point. Mike Vrabel — being Mike Vrabel — has been able to squeeze an extra season out of an undercooked core. This offseason will present tough questions: do they pull the ripcord and hurl head first into a spread-option future? Do they stumble along with the Tannehill-Henry duo, hoping for one final ride? Do they try to upgrade the QB spot, sliding a wide-zone-then-boot merchant into the Henry-backed offense? Do they bet on Willis to grow and develop as a more traditional quarterback?

The latter feels unlikely. Selecting Treylon Burks and Willis within the same draft felt like a bid by ex-GM Jon Robinson to push the Titans down a different path. Drafting Burks, a pace-and-space, spread-option receiver who ran only a handful of routes in college alongside Willis gave the Titans the potential for a different path forward. The incongruence between the styles of those players and the program that Vrabel has built might explain why Robinson has spent the last month polishing up his résumé and scanning LinkedIn.

Perhaps Vrabel signed off on that future shift in philosophy. Maybe that’s who the Titans want to be in the post-Henry world, moving closer to the Eagles' way of doing things than the Niners or Rams.

Maybe not. Maybe trying to squeeze Willis so vigilantly into the more traditional box was about sticking two fingers up to the front office or chucking a player into the deep end to see if they have any shot at reaching the required level by his sophomore campaign. And if not, it’s tough luck, rook.

The Titans have more information than anyone on Willis. They know what kind of worker he is and how dedicated he will be to trying to fix his mechanical flaws over the offseason (and the offseasons to follow). Right now, he could not be farther away from fitting into the kind of system the Titans want to run to maximize Henry.

Deciding whether to pursue a culture change in a post-Henry world is a decision that will come to define the next cycle in Tennessee. Mapping a path forward where Willis and Henry work together next season is tough. And that will force Vrabel and whoever winds up with the full-time GM job to chart one of two courses: To move on from Henry early, before injuries and age start to catch up to the point it submarines the offense, and turning the roster over to a true spread-option style for the short-term; or to chase another veteran option who can slot into the Henry-backed offense and offer a little something beyond Tannehill, punting on the Willis project, a project that might never see any pay-off.

It doesn’t seem like a difficult decision. But is a decision that could be the difference between Vrabel heading back to the playoffs in 2023 or scanning Zillow for homes in Columbus.