Why Vance Joseph should top the list of NFL head coaching candidates this offseason

Joseph has earned a second shot at a head coaching gig

(Full Disclosure: This was originally intended as a topper to a Black Monday column, and it was written before Brian Flores was fired by the Dolphins. I… did not see that coming. Flores fulfills a whole bunch of the arguments I’m about to lay out for Vance Joseph, and he has proven to have his bleep together from a big-picture strategy perspective, even if there were some real wonky choices and the Dolphins are now trying to assassinate the character of the man on the way out of the door, a shameless bid from Stephen Ross, Chris Grier, and company to cover up for their own incompetence. I say that to say: My list would now start with A) Flores; B) Joseph. So this is now exclusively about Joseph — there will be a second piece out later today on the current head coach openings in general, playing matchmaker for those roles.)

Let me start with this: If I was asked by one of those fancy consulting firms that help NFL owners find head coaches who they should recommend in this upcoming cycle, I’d have one answer: Vance Joseph.

(BTW, I am routinely asked why NFL and college teams hire consulting firms, only to land on the betting favorite, the hot-shot head coach, or a has-been taking one final payday. The answer: Firms are hired to do background checks, and to offer a team a degree of distance, both in terms of PR and litigation, if anything about that candidate is unearthed once they’re in the job. It’s not paying a million dollars to be told to hire Brian Daboll; it’s a million-dollar insurance policy in case something goes wrong or is unearthed after the team has hired Daboll.)

I’m a believer in the idea of the second-chance coach, particularly if that coach had his first crack at the top gig at a young age. There is any number of reasons why a coach doesn’t work out in one spot: Dodgy personnel decisions; betting on the wrong quarterback; an iffy culture. One decision can sink everything, but that doesn’t mean the coach is incapable of doing the job elsewhere in the future.

Sometimes, the coach has yet to find his voice. At the very start of my scouting career, I worked with former Denver Broncos general manager Ted Sundquist. Sundquist was not part of the group that hired and then fired Josh McDaniels. He was pushed out as the team looked to go in a new direction under the McDaniels model. But he was part of the group that interviewed McDaniels – and he remained an informal consultant after McDaniels was hired.

The McDaniels that the Broncos hired, that the hiring group ran their background research on, was not the McDaniels that showed up at the facility once he was offered the job; he was not the McDaniels that I would cover years later working in Boston.

McDaniels was playing a character. Rather than leaning into his nerdy, teacher-like demeanor, he tried to be a macho man. He was sullen. He was rude. As the head man, he didn’t treat players the same way that he had treated them as a coach. He lost the locker room not because he was struggling to out-strategize opponents, but because the people who were essentially his employees (throughout the building) thought he was a dick.

If you asked those around the Broncos – perhaps McDaniels himself – he was doing a poor impression of Bill Belichick. He believed a head coach had to comport his way because that is what he had seen, and he had seen it with Bill Bleeping Belichick. If players can sniff out anything, it’s a fraud.

A coach being comfortable in their own skin, knowing there is no one way to do this thing, that John Harbaugh and Bill Belichick are not the same, that there’s little correlation between Mike Tomlin and Bill Walsh, is a powerful thing. Only when a coach reaches that point are they ready to run the whole show; it’s why McDaniels has been at the top of hiring lists for the last few years. He’s ready.

By all accounts, Vance Joseph was himself with the Broncos. He was an okay communicator. He worked hard. He focused on defense. He tried not to meddle. He taught.

One box I always look for with a head coach: Are they a teacher? The best of the best are always ready to teach rather than attack. Urban Meyer’s flame-out in Jacksonville was so predictable because he was no longer an on-the-field guru; he was a tyrant. If you look at coaches who have had longevity, they’re first and foremost teachers, often of a specific position group.

Nick Saban still takes daily practice with Alabama’s defensive backs; he probably remains the most effective defensive backs coach in the country. The person who would run him a close second: Pete Carroll. Both spend day after day working with corners – veterans and never-gonna-make-its alike – running over techniques, from feet to hips to hands to eyes, offering painstaking detail, teaching the players. A blown bump-and-run rep on third-down becomes as much their failing as the fault of the player.

Joseph brings a similar style. He is a defensive backs coach by nature. His understanding of the jigsaw of the defensive backfield and how that fits into the geometry of the field is how he’s been able to consistently field high-level defenses, even when lacking talent. He also offers the right defensive philosophy for the here and now. As I’ve detailed previously, there is a whole lot of Bleep It to the Joseph-Cardinals system. They are sending heat all the time, no matter the down and distance.

Tracking the evolution of Joseph has been interesting, though. It isn’t an all-out-attack style for the sake of it. He’s making educated gambles. There is a strong foundation underneath the wonky pressure looks. He has leaned into the five most en vogue trends across all levels of football: Blitzing on first downs; running a host of simulated pressures and creepers on later downs; rolling with a five-man, ‘Bear’ front and light boxes; basing out of a two-high structure and rotating from there; running three safety structures and moving those safeties to different levels of the defense. He has adapted and tweaked his philosophy to the personnel in Arizona, and has built a system that is tailor-made to slow down the sort of attacks that have pulverized defenses for the past five-plus years.

Think about the Light Box theory that now dominates so much of the schematic discourse in the college ranks and the NFL. Think of all those nifty looks and coverage shells that have been (rightly) credited to Vic Fangio and Brandon Staley. Joseph runs the same set-up. But where Fangio and Staley have gotten into some bother is the lack of versatility within their schemes. Based on the personnel in the game, the offense can get a decent idea for the coverage menu and the pressure packages that roll with that.

Where others have faltered this year, Joseph’s light box design has worked. He’s stuck to what the Fanigo-Staley crowd call their ‘Penny’ package – a 5-0 or 5-1 box out of a ‘Bear’ front – and done so with success. Opponents look to get big against the lighter box, adding an extra tight end or back to the proceeding to mash Arizona with the run. The Cardinals have rebuffed it all. Against 12 personnel, they concede just 3.8 yards per carry, well below the league average. Against two-back sets, opponents have just a 38 percent success rate (which notes how will a group does vs. the historical down and distance), ten points below the league average. The Cardinals finished the season third in the league in EPA per play vs. the run. The Broncos finished 18th. The Chargers: 31st.

One crucial difference: Joseph is in constant attack-mode on early downs, even when running a lighter box pre-snap. The light box is itself a sort of gamble: It’s about baiting the offense into running the ball, and then rallying to the run quickly or funneling the run to a specific spot. In doing so, the hope is to eliminate explosive plays on the ground and takeaway shot plays through the air.

Joseph doubles down on that gamble by not just lightening the box and then rallying to the ball, but by blitzing from all kinds of fun and creative angles. If the opposition does run the ball, he doesn’t just want to limit explosives. He wants a TFL. He wants a negative play. Picking up a negative play on first down is, obviously, a defenses best shot at winning a drive. Joseph has taken that idea out to its logical extreme: He is going to bait the offense to run the ball and then send everyone to bury it in the backfield.

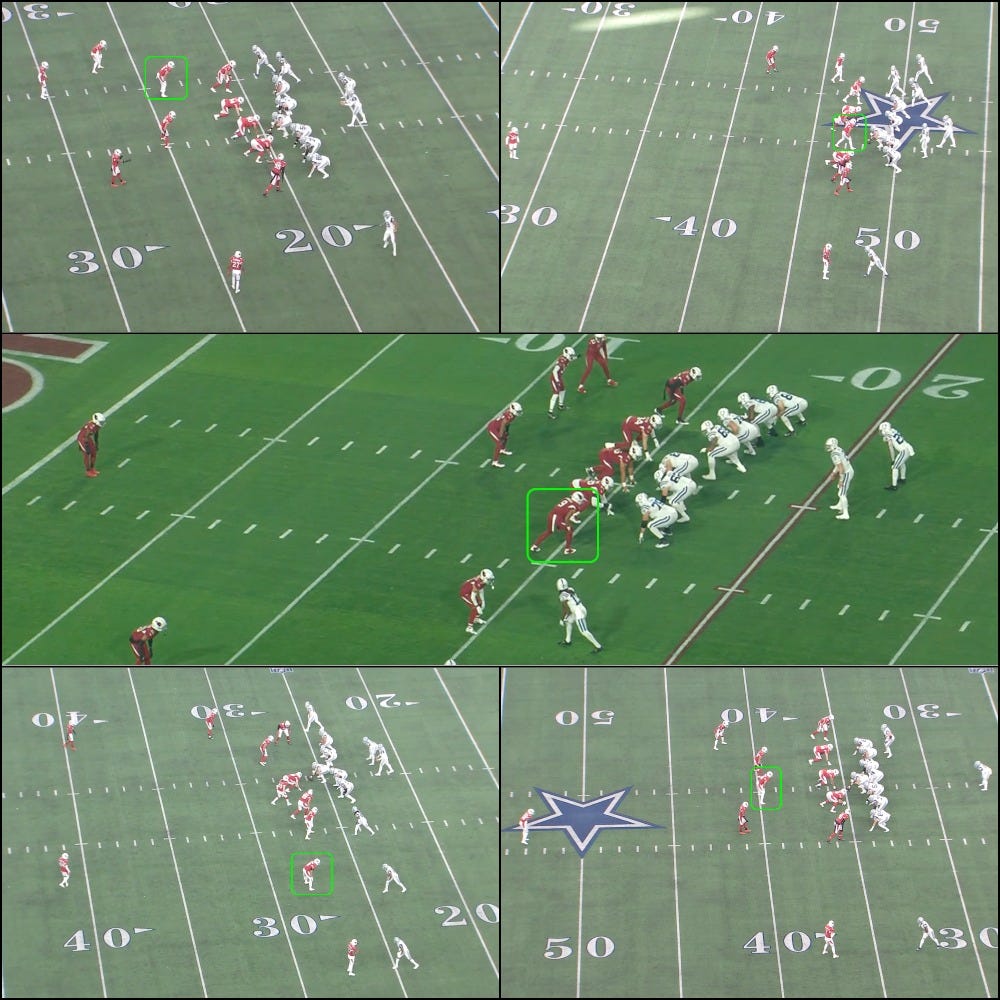

In Arizona, Joseph has the advantage of position-less defenders. Isaiah Simmons functions as a cheat code. Whereas other groups have gotten into trouble with the predictability of their packages, the Cardinals can toggle to innumerable looks with the same personnel thanks to Simmons’ versatility. Simmons can and will line up as Arizona’s box linebacker, overhang, nickel edge-rusher, mugged ‘backer, and is the team’s go-to blitzer:

From the same personnel grouping, the Cardinals can jump into any look – and can switch it up on the fly if need be. And from any and all alignments, Simmons is a threat to blitz, drop into a zone, or match in man-coverage.

Quarterbacks know that pressure is coming when they play the Cardinals, both against in obvious passing situations and vs. the run. But it’s tough to get a beat on what’s coming – who is coming, and from where – based on the pre-snap shape or alignment of the defense. Joseph put Dak Prescott, one of the league’s finest pre-snap chess players, in a blender in Week 17, Prescott checking to plays that would flow directly into the path of an unblocked defender.

It’s not just Simmons, either. Budda Baker, the Cards do-everything safety-linebacker-nickel-blitzer is as impactful and important to his defense and his scheme as any defender in the league. If we’re talking true defensive value – what that player’s skill and intellect unlock for his teammates – Baker is comfortably nestled in the league’s upper tier.

How Joseph uses Baker is often been compared to how Mike Zimmer used Harrison Smith in Minnesota. There are subtle differences, though. Both coaches like to crowd the line of scrimmage with bodies: Mugged linebackers, overloaded fronts, safeties walked down along the line of scrimmage. But where Zimmer would like to drop Smith down to the edge of the line of scrimmage and use him as a blitzer, tight end demolisher, or drop him into one of the flat or hook zones underneath the coverage shell, Joseph will drop Baker all the way back into a deeper position. Both were (and are) looking to bluff a pressure and then back out. But where Zimmer added a degree of conservatism to his bluffs, Joseph leaps to the extremes. It might mean sliding Baker from the edge of the LOS to a half-field zone. It could be slipping from that same spot to the middle of the field, where Baker serves as the post safety in a flat cover-1 look.

I mean, come on now! There’s Baker (#3), hanging out as the weakside safety. He’s pre-rotated, shuffled into the box to present a single-high coverage shell pre-snap. At the snap, the Cardinals rotate. It’s a replacement pressure. Pre-snap, they show a man-free look, cover-1 (one deep safety) with a five-man pressure. Post snap, they deliver a cover-1 look with a five-man pressure, but they get to it through a neat domino effect.

Isaiah Simmons blitzed from the slot. Behind him, the free safety rotated into the slot to pick up a receiver in man-coverage. On the other side of the field, Baker bounced out of the box and slid all the way back to the high post to rob anything in the middle of the field.

It’s simple. It’s effective. It’s brilliant. It’s Joseph using his two most flexible defensive pieces to get to a simplistic coverage through creative means.

The post-snap movement is constant. The coverage shells take on the same flavor, but it’s the presentations that differentiate Joseph and the Cardinals from the traditional crowd.

How about rotating to Tampa-2 from a six-across pre-snap alignment?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Read Optional to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.