The case for Zack Baun as Defensive Player of the Year

The Eagles took a shot on an edge-defender turned off-ball linebacker. It's paying off big time.

If you’re putting together your Defensive Player of the Year ballot, there are a couple of must-have names beyond the obvious sack or interception artists:

Cam Heyward, Pittsburgh Steelers

Zach Allen, Denver Broncos

Khalil Mack, LA Chargers

Brian Branch, Detroit

But don’t leave off Zack Baun, Philly’s do-everything linebacker. Through 15 weeks, the Eagles rank fourth in the league in defensive EPA/play. Since week five, they are first, comfortably ahead of the Lions in second and racing away from the Texans in third.

Jalen Carter has been the Eagles' best defensive player. The transformation of the young secondary has been the unit’s most important development. Early in the season, the rookie-infected group was passive and sloppy. Now, they’re dynamite: a physical, switched-on unit that plays with the kind of wink-wink chemistry that allows so-called ‘match’ coverages to shine – and allows a coach to call an increasing volume of crafty traps, zones, rotations, and matches, the subtleties that have made the Eagles difficult to decipher on the back-end.

Carter is the game-wrecker. The secondary tips the unit over the top. But Baun is the agent that binds the two levels together.

The unit’s growth under Vic Fangio (FAAANGGSS!!!) has been about the collective. But the adaptations Fangio has made throughout this season have been principally because of the growth of the secondary and the versatility of his linebacker duo: Baun and Nakobe Dean.

Baun has 35 – THIRTY-FIVE – run stops this season. Tack on coverage stops, and Baun is up to 63, ten more than any other player in the league. Baun also has a team-leading 14 tackles for a loss or no gain. Add to that, he has totted up three sacks – and has a season-wide pressure rate of 16.3%, a ludicrous total for an off-ball linebacker not playing in one of the mug-centric, read-blitz-heavy defenses in Minnesota or Denver.

He also looks like a cross between your local orthodontist and an NYPD detective, which shouldn’t matter, but kind of feels like it does.

Baun’s evolution from an iffy sub-rusher playing on the edge to one of the league’s most versatile and imposing off-ball linebackers is one of the most crucial developments of the season. In New Orleans, he was miscast. The Saints tabbed Baun 74th overall in the 2020 draft, selecting him in the third round after he put up massive production for Wisconsin. During draft season, he became one of the ultimate stats-v-eye-test guys: He put up 12.5 sacks in his final season and was named a first-team All-American selection, but lacked the traditional measurables (read: size) to garner consideration in the first round.

Instead, the Saints took a flyer that Baun’s effort, tenacity, and intellect could see him round into a valuable rotational piece. Maybe he wouldn’t be a star pass-rusher, but he could be a valuable cog in an electric pass-rush, a player happy to subsume himself to the scheme who would bring all-out effort down in and down out – and sprinkle on some much-needed versatility.

But it didn’t work out that way. Baun was largely relegated to a role on special teams with the Saints. In four seasons with the franchise, he posted two sacks and measly pass-rush win rate and pressure totals. He was only offered a shot as a rotational edge-rusher in his final season, after which the Saints were happy to wave goodbye to a top-100 pick before he reached his second contract.

The Eagles swooped in to grab Baun for $1.2 million, moving him off the ball to a spot as an early-down linebacker. The reward: good God.

It is rare for any linebacker to look the part right away. Even the most polished prospects typically need three seasons before rounding into shape in all facets of the position. But Baun has stepped in… right away… as an All-Pro player.

The numbers are eye-popping, but the process behind them is just as encouraging.

Baun has been everywhere for the Eagles defense. He is a walking dose of Adderall, roaming across Philly’s front and swarming all over the field. He has good instincts, digests information fast, and once he commits, he’s gone; there’s no hiccup in his process. He can explode downhill or tap-dance through crevices in the front. He spins magic out of the mundane. And his malleability has allowed Fangio to adjust the structure of his defense.

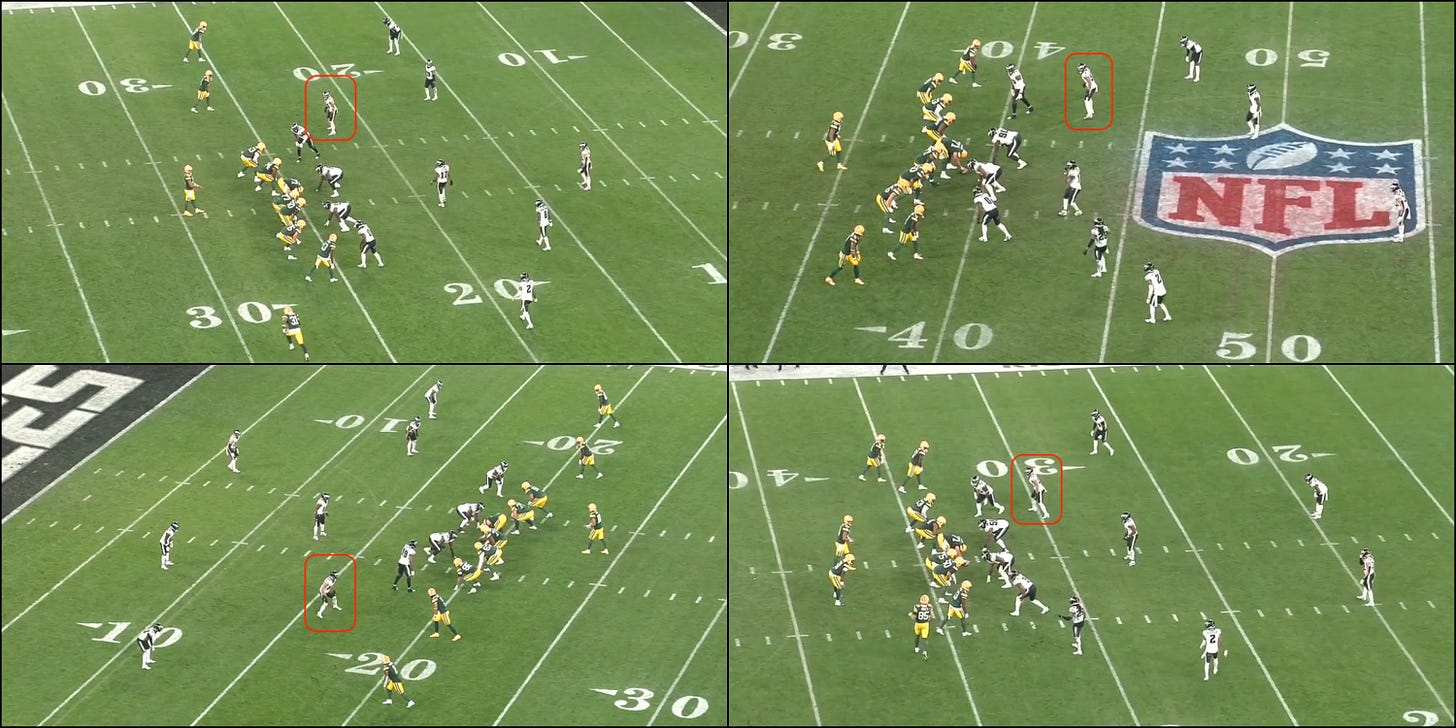

In his first game for the Eagles against the Packers, Baun notched career highs in tackles and sacks in his new role. Moving him off the ball tapped into some of his potential zooming downhill. But even in the Brazil Bowl, things were a touch off. Baun was routinely slotted into an overhang position, the corridor between a tackle and a slot receiver. From there, he could fit the run on the perimeter, spike inside an edge defender, blitz, effectively, from a tighter alignment near the alignment, or drop out and match a receiver in coverage.

In his wider role, Baun rushed the passer 13 times — a season-high.

The numbers were gaudy. But the structure of the Eagles’ defense was not particularly sound. Baun wound up with lofty tackle numbers because the Eagles were not clean against the run at the first level. The defensive line was outnumbered or pushed off the ball, freeing backs to climb up to Baun who would then corral the runner and juice those nice tackle figures.

Baun’s individual figures were tasty, but the Packers still rushed for 159 yards and averaged 8 yards a carry, including 119 yards in explosive runs. It was much the same in week two against the Falcons. The most predictable run game in the league, featuring a static Kirk Cousins and a new-found embrace of a pistol-based offense, churned out 155 yards on the ground, averaging 5.1 yards a carry and more than two yards before contact.

But in week three, Fangio made a series of key defensive adjustments. He shuffled Baun from his role as off-ball ‘backer-slash-overhang defender and moved him into a walking linebacker role in the ilk of Germain Pratt, back when the Bengals defense was fresh, creative, could stop anything, and Pratt could still move (excuse me while I weep).

Like on the back end of his defense, Fangio’s goal was to change the picture for the offense pre- to post-snap – or, rather, while the opposing quarterback was rattling through his pre-snap operation. Remember those heady days of the Saints offense? For two weeks, they clubbed everyone in sight. Their motion, shift, and play-action rates were through the roof. So was their explosive play rate. They protected their line with a ton of movement, and baited defenses into busts with savvy route structures that allowed Derek Carr to attack down the field.

Fangio and the Eagles defense blew that apart – and Baun was key.

The Eagles moved constantly pre-snap. They still rolled and rotated on the back end – as is demanded in the Fangio doctrine – but they moved in the box, too. And this was not about bringing extra hats to the proceedings, it was about altering the look of their front. They routinely walked, moved, and stemmed from 4-2 or 5-2 boxes to get an extra body on the first level (the defensive line), forcing one-on-one blocks or the Saints’ line to switch their assignments right before the snap, leading to busts.

The Eagles played with 6-1, 6-2, 5-2 and even 6-3 fronts, cramming the first line with as much mass as possible to limit the Saints’ go-to doubles, with Naboke Dean standing off the ball as a sift-and-find (match the back) linebacker. It was devastating. The Eagles made the box claustrophobic and confusing.

Stemming gives a defense the illusion of complexity but actually makes things easier on a defensive front. Pre-snap line stems create the appearance of complexity, that something is happening while simplifying assignments for the front. Rolling a linebacker down and kicking everyone over a gap adds some sauce on top. It places blockers in conflict, forces the offensive line have sound blocking rules (and to be keyed into their pre-snap communication), and makes it tricky for that group to zip up to the second-level quickly, keeping the off-ball linebacker (or linebackers) clean. The ultimate upside: negative plays.

There was extra beauty to the Fangio plan. Motioning and shifting are now used as shorthand for ‘good offense’. And there’s some truth to that: motion at the snap is damn difficult to deal with. But even when the Saints were pasting fools in the opening two weeks, their motion and shift rate was a tad bit of a mirage. They were resetting their formation as much as motioning into a play. That gave the Eagles a tell. They could move, stem, and re-adjust their front based on the Saints' motion or shift. One of the difficulties of stemming frequently – why teams do not do it all the time – is that it’s tricky to time up. With the volume of motion at the snap on the rise across the league, it’s difficult to know when to move, where to move to, and who should move. A defense can wind up out-gapping or out-leveraging itself by stemming. It’s why it’s usually the reserve of short-yardage situations or down at the goal line. But the Saints' approach to pre-snap movement allowed Fangio to trigger his movement with confidence. The Eagles would set up, wait for the Saints to indulge their pre-snap movement, then Fangio would pick up his front, shuffle it across, and walk Baun down to the line.

Teams use both pre and post-snap stems – exchanging gaps after the snap. And there are counter stems, too (stay with me. This matters). Typically when you stem pre-snap you’re trying to time it up with the cadence of the quarterback, move everyone one gap, and force the o-line to communicate with little time and adjust their responsibilities. You can also stem post-snap, exchanging the gap from the one you’re lined up in. Then there are counter stems: where you move gaps pre-snap AND THEN exchange the gap post-snap. Against the Saints, Fangio rolled out everything — and it’s a style he has stuck with all season.

Defenses typically stem or kick their off-ball ‘backer down based on the cadence of the quarterback. If they have a tell, the line knows when to move. But the NFL is so crafty at juggling snap counts and tweaking things week-to-week that it’s tough to execute at the pro level. But as we have moved into a movement world, smart DCs are now figuring out how to time up their pre-snap movement to coincide with the movement and tell of an offenses motion and shift package. And no coach has been more dialed in about when, how and who to move or stem based on the pre-snap plan of the opposing offense than Fangio.

Fangio gets a ton of praise for his defensive system. And that’s fair. But he’s been around a looooongggg time. He’s run the same defense for a loooonggggg time. What differentiates him from his pretenders is his week-to-week plan. The rules do not always change; the coverages hover around the same mark. But knowing when and what to call, recognizing and understanding tendencies, and attacking tells is what sets him apart.

Fangio has multiple masterpieces. But what he unspooled against the Saints was as good as it gets – and it set the stage for a re-think in the Eagles’ early-down approach which has carried throughout the season.

Baun finished with five tackles and two run stops against the Saints, some way down from his evening in Brazil. But it was his role that unlocked the Eagles’ front – and helped shut down what was, at that point, the most explosive and efficient offense in the league. The Saints averaged only 3.1 yards a rush on their way 89 total yards on the ground; they popped only one explosive run; the 33.1% stuff rate the Eagles hit is still the highest the Saints have conceded this season.

It was vintage Fangio, reminiscent of his approach against Sean McVay’s Rams in 2018, a gameplan that triggered Bill Belichick’s approach against the Rams in Super Bowl LIII.

It was a savvy strategy. In the modern game, defenses cannot be static. It’s tricky to play in heavy looks – five down or six down – and not be naturally forced into a static front. Usually, a team rolls an extra interior defender on the field to close down all those internal gaps, presenting a five-man front so that they have enough beef to bang away against the run. But that can leave defenses vulnerable to pre-snap overloads (motioning into a block) or play-action shots, with a coverage defender subbed off the field for a heavier run defender. Fangio has been able to find balance by slipping Baun down to the edge and kicking the rest of his front one gap inside.

Muddying assignments is the name of the game upfront. On base downs, in their move looks, the Eagles' plan of attack is to force one-on-one blocks, have five or six defenders engage immediately, dent the front, have someone penetrate the backfield, force the running back to slow their path or shift the point of attack, and have Dean or another second-level defender mop up the runner. If you can draw up one-on-one blocks for Carter while remaining numerically sound in coverage, he will happily blast everyone for you.

It’s fairly simple. But it’s proven damn effective. Since that week three game, the Eagles are first in run defense EPA/play and fourth in defensive rush success rate. On first downs, when they let Baun wander, they are first in EPA/play and second in rush success rate. Against heavier looks (multiple tight ends or an extra linemen), Philly is first in both.

Fangio is renowned for wanting to fit the run with a light box, giving him the chance to run all the whacky rotations on the back end that can confuse quarterbacks in the play-action and dropback games. The Eagles have only run 62 plays this season with eight or more defenders in the box, by far the fewest of any defense in the NFL. The next closest group, the Browns, sit with a cluster of teams in the mid-80s.

But those light boxes do not always mean light fronts. The Eagles' ability to fit the run from 4-2, 5-1, 5-2, or 6-1 boxes is reliant on having an off-ball linebacker comfortable toggling between playing off-the-ball, where he may fit an interior gap, and hanging on the edge as a true defensive end in the run fit. Baun is that guy. His versatility allows the Eagles to play heavy or light – and still stay sound against the run or pass. He is the linchpin of the early down success.

The roaming style has hung around every week. Sometimes, the Eagles back off, with Baun playing classic off-ball football and Fangio trusting his line to win on their own with an early-down plugger (one of Baun or Dean) helping to create a five-man wall at the snap. Other times, the Eagles max out Baun’s movement sliding him down to the line late in the snap count. But the option is always there, right on the surface, ready for when Fangio needs it most.

Moving alone is one thing. Making it effective is something else. The tactic would be neutered if the player doing the moving cannot hang in several roles. They have to be a plus off the ball in their designated spot while filling in as a heavy edge-defender who can bang away in the trenches. The move ‘backer also has to show they can slide out into coverage from the edge spot if required, which is why Pratt was instrumental to the Bengals in their deep playoff runs. Baun offers that, too.

Can you slide out into the flat to protect against the boot? You got it, coach.

How about sinking back into coverage and catching a crosser splicing across the formation? Yep, Baun has it sorted.

What about rushing from that spot? C’mon. For Baun, that’s old hat.

That’s the distinction between Baun and Pratt, even at the apex of his powers. Pratt was an effort player up on the line. But he didn’t have the chops to be a true rushing threat if the offense pulled the ball from heavy looks to take a play-action shot. He was a trier but was not proficient at beating blocks and chasing QBs. Baun is. It’s what he’s done his whole life – save for this season in Philadelphia.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Read Optional to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.