The League That Rex Built

Defensive football in 2025 falls into a handful of buckets. Are you a part of FangioBall, mimicking Mike Macdonald, or is your name Brian Flores? Yet all approaches tip the cap to Rex Ryan

“We’re all copycats in this business,” Nick Saban once said. “I haven’t invented anything. I’ve always watched what Rex does.”

When you think of Rex Ryan these days, you probably picture the grin on ESPN. The teeth are glowing. They seem too big for his face. The tan is Trump-brand orange. At this point, Ryan looks like retirement. He probably smells like Miami. If you tune in for his analysis, the big fella is probably about to air some long-held grievance against an assistant who spurned him back in the day, or take a cheap shot at a famous quarterback to fuel the four-letter networks’ need for clicks.

If you think long enough, other things may pop into your mind. The foot fetish. Sanchize. The teeth. The 2000 Ravens. Eating a goddamn snack. The teeth. The 2006 Ravens. Belichick. Back-to-Back Championship games. Ray. Ed. The teeth. Rob. Buddy. The teeth.

The Rexy-ness of all things Ryan has obscured something profound: his place as the defining architect of defensive football in 2025.

Ryan hasn’t coached in eight years. Besides the Jets, he can barely get a team to return his call at this point. But his impact on the game — in the pros and college — has never been more present.

If you’re drawing up a Mt. Rushmore for how things look in modern defensive football, Nick Saban and Bill Belichick will be etched in place. The final two spots are a blood bath. You can argue over Dick LeBeau, Steve Spagnuolo, Pete Carroll, or Vic Fangio. All are deserving. You could build solid cases for names not typically placed in the modern pantheon (Dennis Allen, Wink Martindale, Don Brown, Vance Joseph). You could even latch onto one of the younger coaches who have quickly reshaped thinking across the league (Mike Macdonald, Dave Aranda). The young pups have revitalized ideas, making subtle tweaks to the classics. And they have flipped long-held defensive wisdom to take on fresh challenges over the past three seasons. Whether that was the pace-and-space era or the resurgence of the wide-zone-then-boot style of offense, the best and brightest from the new school have dipped back into the archives and dusted off approaches from 30 years ago.

You could even, if you were generous, make an argument for another batch of coaches, including those who veer way off to the opposite end of the spectrum from the confuse-and-clobber approach that has taken hold over the sport: Robert Saleh and Dann Quinn. Both have influenced thinking. But they have also incorporated ideas from their pressure-happy contemporaries to keep pace with modern offenses.

Then there is Brian Flores. Flores is an auteur in a league filled with coaches rolling out Best Of albums. Yet even top coaches realize Flores is Not Like Us. Flores is doing things — toying with ideas, toying with offenses — in a way that breaks all the established rules. Flores’ outsized blitz rate has become his calling card in the public imagination. But it’s not the blitz rate alone that separates Flores from his peers. Plenty of coaches blitz. They’ve blitzed before Flores, at higher rates. They will blitz after Flores, probably at higher rates. The difference is that no one has shown such a dedication to the craft of pressuring and blitzing the way Flores has: juggling the mechanics of his blitz and pressure structures from year to year, then week to week. Flores took the minutiae of other schemes, cool tweaks against specific offenses, personnel groupings, or formations, and made them the whole of his philosophy. He looked at decades-long rules and asked ‘Why?’ Why can’t you split your defense into three, clean levels? If read-blitzes are effective, if they’re the defensive versions of RPOs, why shouldn’t they be the bedrock of a team’s entire blitz structure? Why can’t you send five, six, or seven defenders in the pass-rush with two-deep players in coverage? Why can’t you send five attackers with four players deep in coverage? Who cares about the ocean of space those players leave behind if the point is to bamboozle the offense, to score easy pressure. If it’s effective, who cares?

Flores lives in a universe of his own. Coaches across the league have pinched elements of Flores’ preferred designs. But Flores, for all his Machiavellian intentions, hasn’t fully reshaped the league. He does his thing. Some have looted certain strands, but no one has had the balls — or skill — to fully implement Flores’ system. And Flores, like everyone else, is standing on the shoulders of the giants who went before him.

So we can quibble about which names should sit next to Saban and Belichick’s. My vote is for Spags. But one name is inarguable: Rex Ryan, the revolutionary in plumber’s clothing.

Ryan ultimately failed as a head coach with the Jets and Bills. But take a look around the league today. There isn’t a defense anywhere that hasn’t channeled Ryan’s vision, whether that’s his big-picture strategy or down-to-down tactics. The mainframe of modern defensive football has Ryan’s imprint all over it:

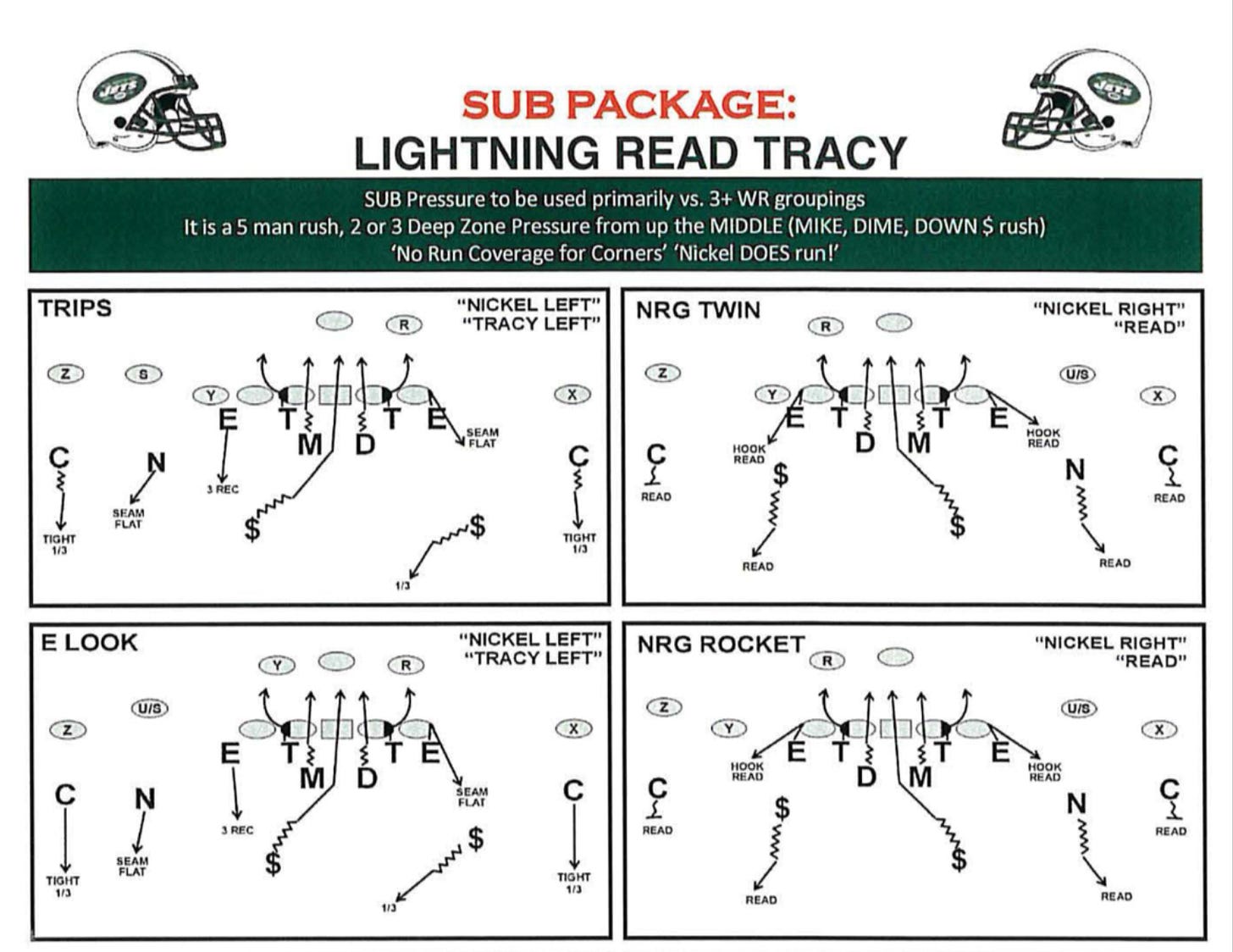

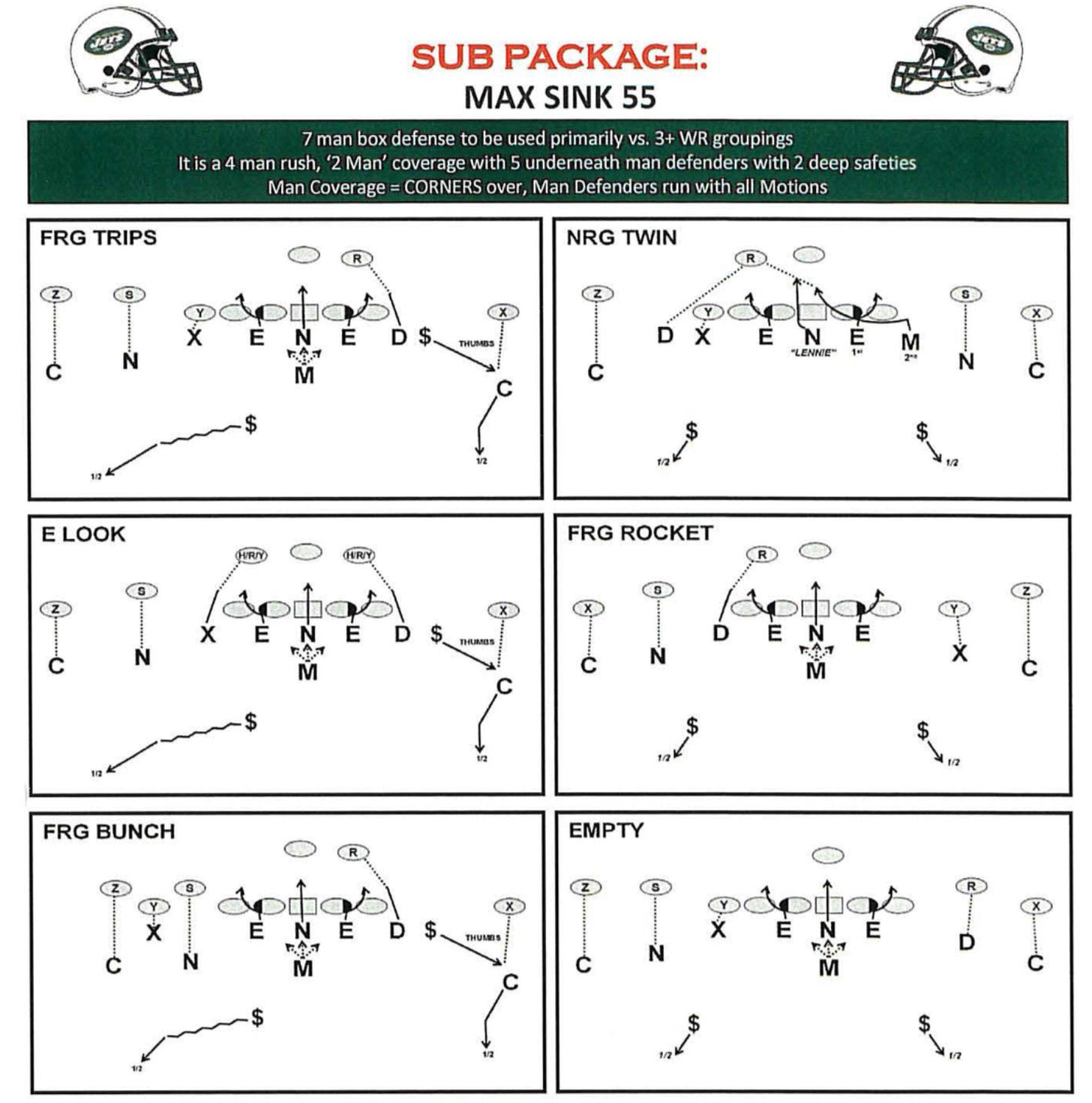

Wonky blitz looks. Sub pressures. Simulated pressures. Read blitzes. Zone pressures.

Pairing overload fronts with pressures.

Figuring out how to set the offensive protection so that the defense can then demolish it.

Everything that this here newsletter harps on about — to, admittedly, an annoying degree — can trace its roots back to Ryan, in some form or fashion.

Even Flores, for all his individualistic flair, has Ryan to thank. Tell me: Who is Flores’ most-trusted confidant these days, the designer of some of his wonkiest ideas? Oh right, it’s Mike Pettine, Ryan’s long-time Chief of Staff.

Without Rex, do we get to Macdonald, Joseph, Flores, and the style that has proven to be most effective in the league today? Probably not.

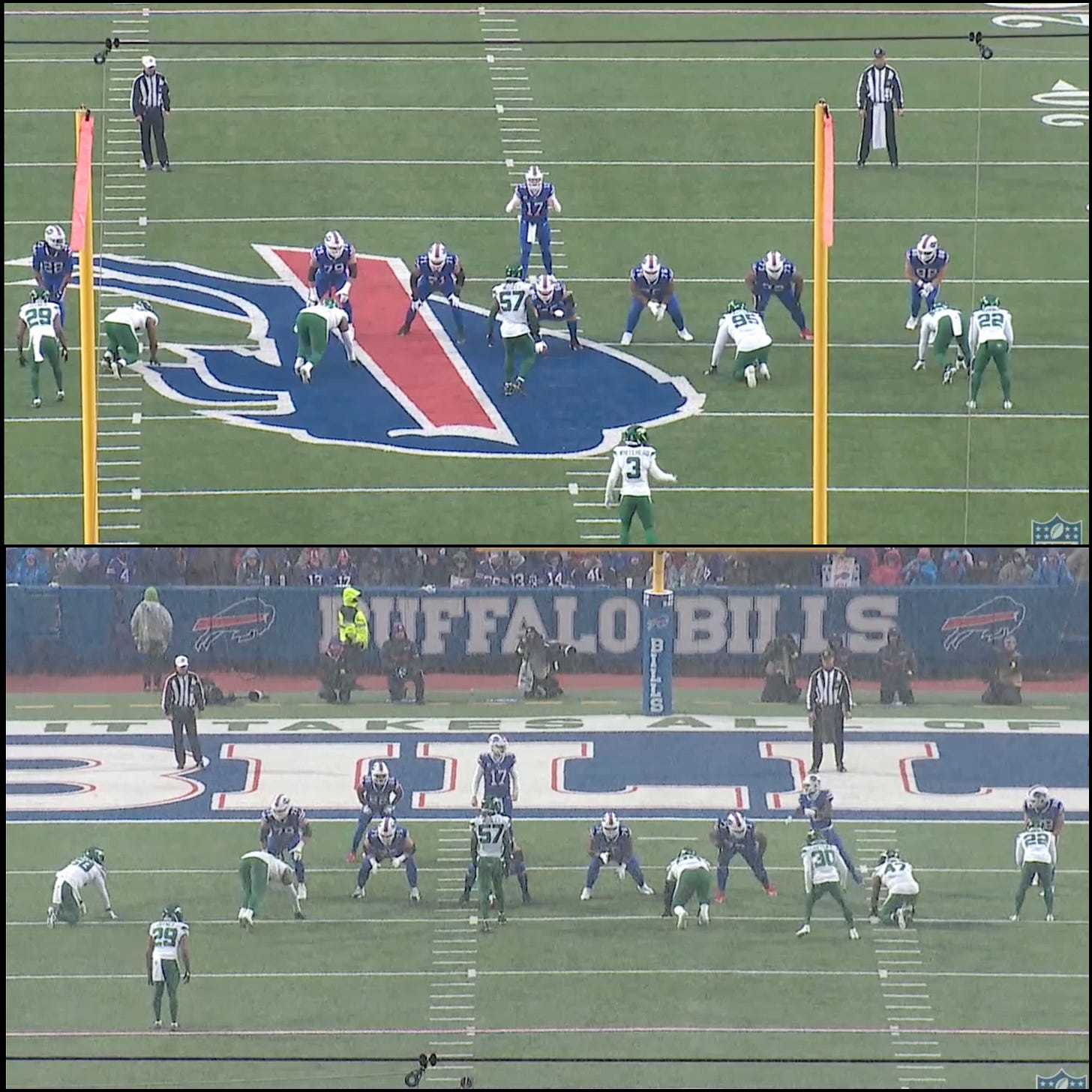

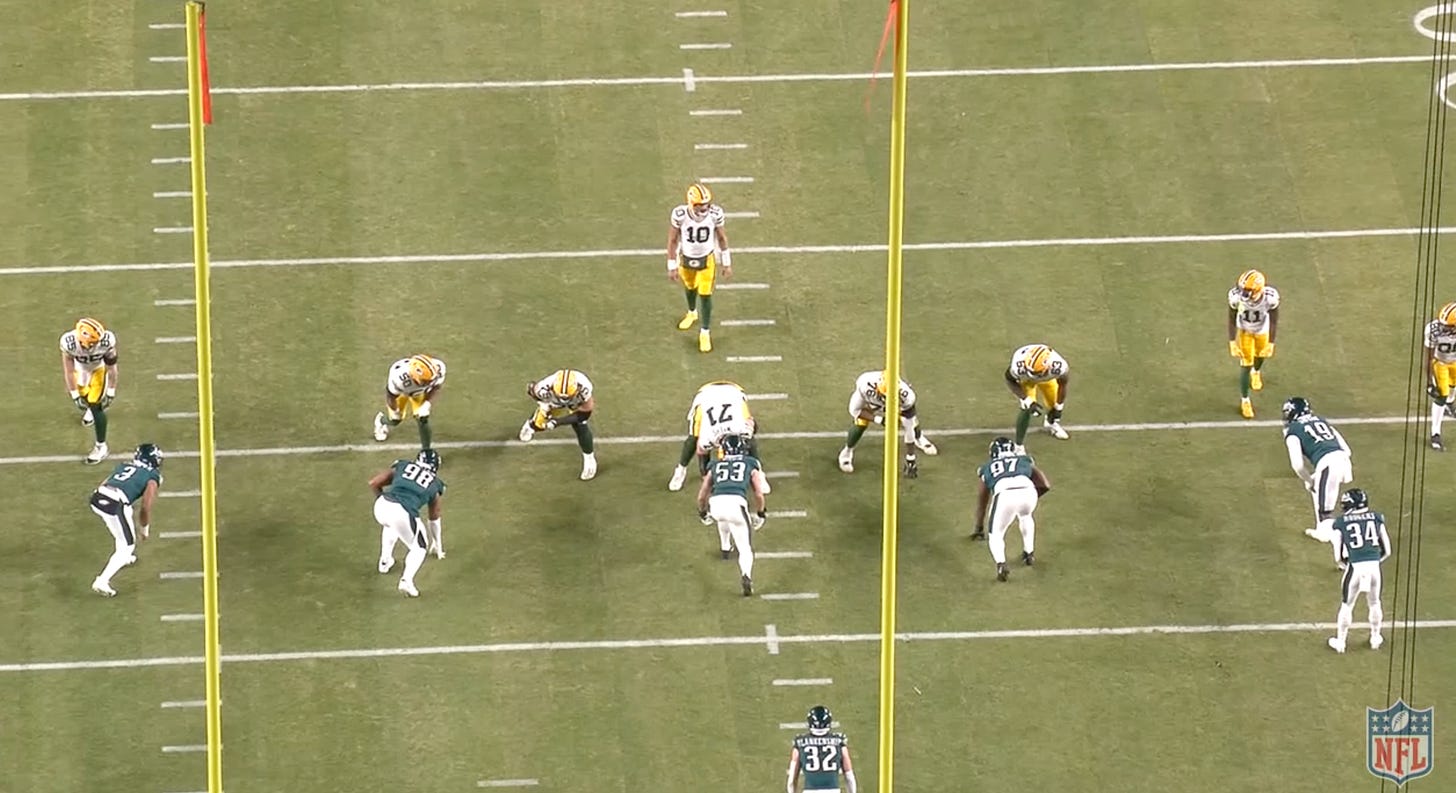

Take last season. The most impactful, inventive, and lauded defenses had the same look, feel, and core tenets of Ryan’s best work. The top-five defenses by EPA/play in 2024 were the Broncos, Vikings, Eagles, Packers, and Chargers. A few of them had direct connections to Ryan’s old staffs, but all of them lifted ideas directly from Ryan’s units in Baltimore, New York, and Buffalo.

Here is just a smattering of current coaches who worked for Ryan at some point during their career:

Mike Pettine, Ryan’s closest lieutenant, is now working up close and personal with Flores in Minnesota as the team’s Assistant Head Coach.

Anthony Weaver, current Dolphins DC, and the Assistant Head Coach in Baltimore while Mike Macdonald was the Defensive Coordinator.

Jim Leonhard, Defensive Assistant (read: pressure designer) with the Broncos.

Karl Dunlap, Defensive Line coach with the Steelers.

Jim O’Neil, Defensive Assistant and Safeties coach with the Lions (who also employ Rex’s son and hold an annual Rex Day during training camp).

Mike Smith, the new outside linebackers coach in New England.

Add it up, and that’s connection points to five of the top-10 defenses by EPA/play last season, including the top-two in the league. And all of those defenses were based, to some degree, on pressuring or disguising — and disguising while pressuring, Ryan’s calling card.

Push it further, and you see Ryan’s influence everywhere. There is Chargers DC Jesse Minter, who spent years working with Macdonald, Weaver, and Wink Martindale in Baltimore and at Michigan. There is Titans DC Denard Wilson, who also worked for Weaver and Macdonald. There is Raiders DC Patrick Graham (maybe the best single designer of pressures in the league), who has a long-standing connection with the Ryans. You can draw those touch points out further to Pettine, Martindale himself, Dean Pees, Vic Fangio, Chuck Pagano, the Harbaughs, and other Ryan confidants. Think about all the branches that have fallen from those trees. That’s eight coaches who, at some point, worked with Ryan or were shaped by his iconoclastic ethos: Spags, Teryl Austin, Leslie Frazier, Shane Bowen, Jeff Hafley, Bobby Babich, Josh Boyer, Vance Joseph, Aaron Glenn, Jonathan Gannon, Ejiro Evero, Brandon Staley, Joe Whitt Jr. and on and on the list goes.

For those keeping track, that’s 18 current head coaches, defensive coordinators, or assistant head coaches — and it’s not a complete list. Roll back two seasons, and there were even more Rex Disciples marshalling defenses in the NFL. The volume of position coaches and assistants is almost never-ending. As is the list of younger coaches who are now being shaped by Ryan’s ideas due to the HC’s and DC’s they’re working for.

Everywhere you look, there are tangible and tangential links to Ryan’s work. Add in those units, and we’re up to eleven out of the top-12 defenses in 2024 having some connection to Rex Ryan. ELEVEN!

As a defensive architect himself, Ryan’s masterpiece was the 2006 Ravens. He may argue it was the 2008 Jets, when he turned a lackluster group into the No. 1 defense in the league, without the help of Ray Lewis, Ed Reed, Haloti Ngata, and Terrell Suggs. But you could also argue (fairly) that Ryan’s greatest impact was in Minnesota, Denver, Seattle, LA, Green Bay, and Baltimore last season. His legacy isn’t just playing on, it’s thriving.

“My Dad is one of the best to have ever done it,” Ryan told the Pivot Podcast last year. “I think I’m better.” He is not wrong.

Ryan’s defensive doctrine was simple: attack, attack, attack. But, to Ryan anyway, that wasn’t just rah-rah talk. Nor was it simply a matter of X’s and O’s. It was a philosophy he felt in his bones. “I never attack on their terms,” Ryan said at a 2001 coaching clinic. “I attack on my terms. Not the offensive terms.” It was a relentless approach. A vicious approach. A we-don’t-care-if-you-are-Peyton-Manning sort of deal. You have to deal with us.

Ryan did not invent all of the specifics of his defensive approach. He stole from everyone and iterated on their ideas. He took base elements from his dad. He took from Bill Arnsparger, the Godfather of hybrid defensive structures. He robbed Dick LeBeau blind. But he took those ideas and pushed them out to the outermost extremes — and created new ideas that built on those foundations.

For Ryan, aggression was everything. His scheme was straight gasoline. He talked loud; he talked tough. He wanted his defense to be the most physical unit in the league, to deliver real, actual punishment to anyone who dared line up across from them. There should be a price to pay, Ryan once said, for stepping onto the field with his defense. No matter that the laws of the game (rightly) encourage player safety, this is a violent sport. And Ryan wanted his units to be the most violent. He wanted opposing offenses to feel the throbbing and nagging weeks after they squared off against a Ryan side. “All I ever saw with my dad was ‘be the more physical team’. I inherited that,” Ryan told the Pivot Podcast.

But Ryan, like his dad, was no neanderthal. He wasn’t just talking about tackling and hitting and screaming. That sense of aggression infused his ideas about the game more broadly. Forget the bravado. Forget the language. Forget the caricature. Ryan may not want to admit it, but he was an artist. And he was an artist who knew how to get his lofty ideas and message across to a locker room. Players didn’t need to know the high ideals. They just needed to execute their assignments — and execute them aggressively.

To ensure his players could play aggressively, Ryan made the teaching easy. One word calls. Dopey analogies. Buzzwords. As a defensive line coach, Ryan taught two or three blocks and two ways to react. Anything else would be overkill. By stripping the components back, he allowed his group to play fast and physical, without doing dumb, fancy stuff like thinking. Once he slid into the coordinator’s chair, he followed through on that mindset. And once he moved to the top job, he went totally dollaly. The teaching principles were simple, but stored in his head was a fountain of highbrow ideas. Different ideas. Unique ideas. Ryan wasn’t interested in mastering one style of defense. He wanted every option on the table; to master them all and then, when he ran out of influences to use, to generate his own. Every front structure you’re thinking of: check. Every coverage: those are there, too. How about disguising and rotating? That’s there in abundance. What about the pressure game? Ryan created novel concepts that have now filtered through every playbook at all levels.

Ryan was a defensive warlock. He understood the game at a higher level, could see the patterns developing before anyone else — both in terms of meta trends across the league and when simply watching things unfold on the sideline. “I can see the whole field,” Ryan said. “I don’t know why. Most coaches can see two or three guys”. He could track, in real-time, the individual tendencies of players, and had the imagination, cojones, knowledge, and playbook to flip on a dime and break an offense apart.

The big-picture outlook of his unit — what he called and when — was just as aggressive as the individual players popping someone at the line of scrimmage. He didn’t care who he was facing. Sometimes, the down-and-distance was irrelevant. If he spied something, he would attack it. At times, it looked chaotic, but it was organized chaos.

“The way Rex saw the game, you cannot put into words,” former assistant Mark DeLeone told the Make Defense Great Again podcast. “He is to defense what Steve Spurrier and Mike Leach were to offense. He is not the norm. He doesn’t follow the rules. I was only with him for one year, and I think about him every day.”

The battle between an offense and defense has traditionally been thought of this way: the offense knows what it’s doing, knows when it’s snapping the ball, knows what it’s running and where everyone will be; the defense reacts. Fuck that, was Ryan’s philosophy. We know where we’re going, too. He set to work dictating his terms, forcing offenses to adjust to his approach. By rattling through a succession of front structures, personnel, and pressures, he stole back some of the initiative from the best offensive play-callers and quarterbacks.

(That’s probably why Peyton Manning, the game’s top code-breaker, was the only quarterback reliably outwitted Ryan’s bizarro looks.)

Ryan would spend three hours each offseason with Bill Walsh. His thinking went: if this is the greatest offensive scheme designer of his or any lifetime, let me learn all the things he doesn’t want to see from a defense… and I’ll run those. Walsh walked Ryan through every plausible protection plan, through offensive thinking and tendencies, and all the ways he would break down Ryan’s unit. Those conversations allowed the defensive guy to consistently stay a step ahead.

Ryan was an early signatory to the idea of inverting the downs. Traditionally, first and second down — and third and short — defenses, well, defend. For the bulk of Ryan’s career, those were run-downs. On third and medium-plus, it was the defense’s turn to have some fun and attack. That’s when DCs could roll out their blitz packages or funkier looks. But Ryan wasn’t about that life. Why cough up those first two downs? Why not have fun every time? Why not attack every time?

“We are going to make the offense react to us,” DeLeone says. “He would call three-down, overload pressures on second-and-seven. We would go ‘what if they do that?’ And he would go, ‘But what if we do this?’

Ryan was maniacal about breaking down the mechanics of protections. “When you hit the quarterback, the entire team feels it,” Ryan said. There are only so many ways to build a wall in front of a quarterback; Ryan looked at every conceivable way of taking a sledgehammer to them. “Quarterbacks prepare like junkies,” Pettine, who also coached in Baltimore with Ryan, told the New York Times in 2012. “We create things they think they recognize — line up in something they think they saw on film a year ago — then we do something different.”

Coverage assignments are finite. There are only so many different coverage looks a team can roll into. But the only limit to a team’s pressure plan is a coach’s creativity. And Ryan’s imagination for different ways to attack protections was almost limitless.

Attacking a protection is one thing. But firing bodies into the unknown is a roll of the dice. You hope you make the right call against the right protection so that you can puncture it — or that your players can overwhelm the offense in a series of one-on-ones. That would be the neanderthal approach. But that wasn’t Ryan. He was a card-counter. Ryan set to work forcing offensive lines into specific protections based on the presentation of his front — all so that he could unfurl a pressure he knew would break that protection apart.

“When they tested me, my creative thing was the highest ever tested, and so was my problem-solving,” Ryan told the New York Times after being diagnosed with dyslexia. “But I can’t spell! But creative problem solving, that’s what a coach is.”

Problem: How do you break down a pass protection?

Creative Solution: You set the protection for them.

These days, that takes the shape of a lone-mugger: one mugged-up defender hovering in a gap, presenting a five-across look to the offensive line.

By standing a linebacker or safety down by the line of scrimmage, the offensive line has to respect the possibility that the mugger may blitz (it helps if they’ve blitzed before).

Typically, an offense will move into “5-0” or man protection to cover all five potential pass-rushers. From there, the defensive line gets to lay siege, running through a battery of stunts and twists, knowing the offense is most likely in 5-0 protection, a perilous structure against stunts and twists.

That style is at the heart of the pass-rush plans we now see from the Robert Saleh-Niners coaching tree, and all those who play with a four-down-and-go pass-rush.

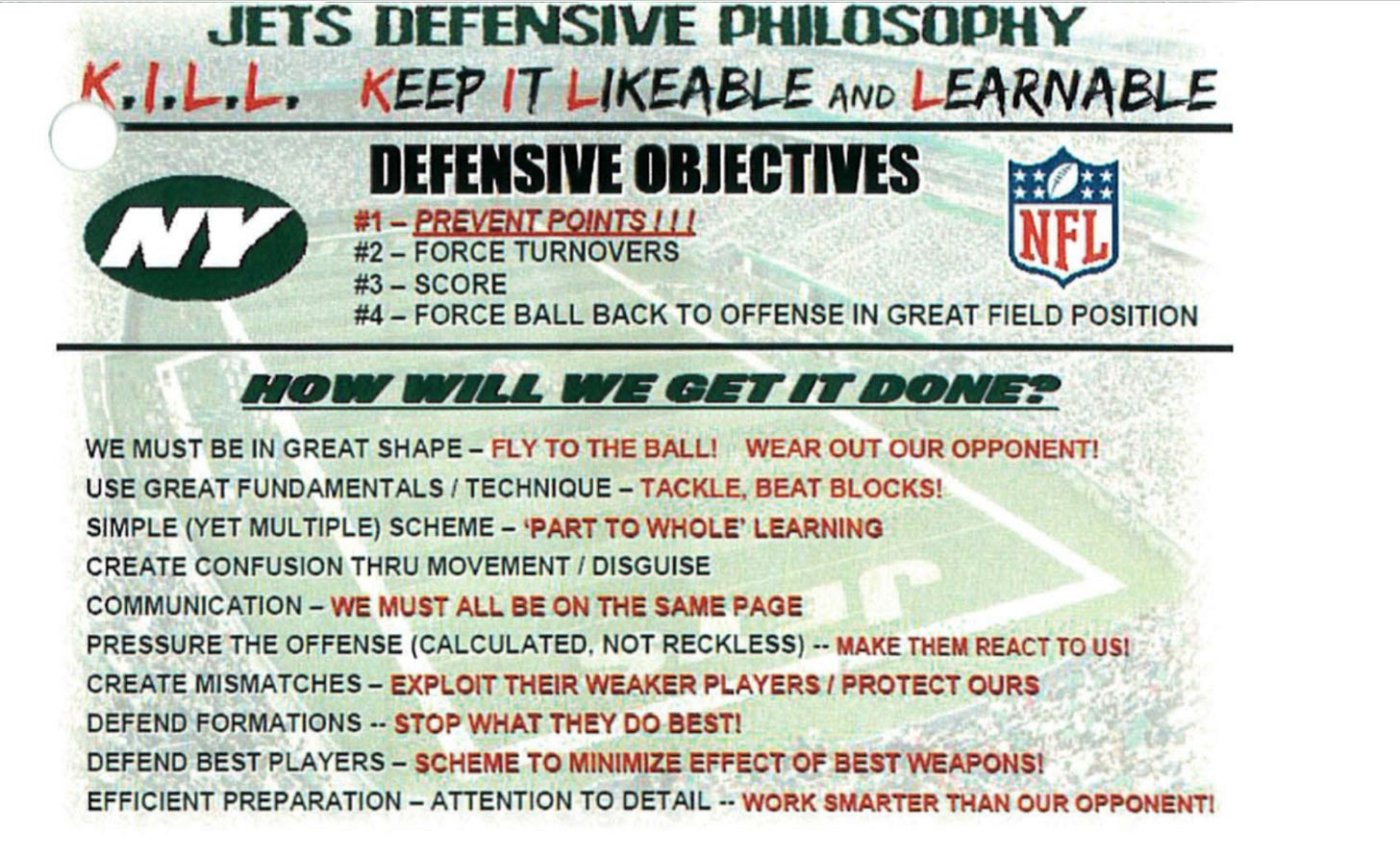

Look at that beauty. There is one of Ryan’s units utilizing the lone mugging tactic back in the day. With one linebacker walked down, the Chargers are forced into man-to-man protection to account for the numbers up front. With a safety also feigning like he’s in attack mode, the Chagers are forced to keep their back in to scan and help out.

From there, the Jets can tee off, stunting away to vaporize the pocket. It’s a four-man pass-rush investment, with the defense knowing the protection. For the offense, they keep six men in to protect against four, with the defense able to flood the back-end with coverage defenders. The quarterback is forced to hold the ball while the defensive line screams off the ball, equipped with the knowledge of what they’re attacking. The result: the pocket gets brained.

Thirteen years later, the long mugger is the go-to weapon for defenses looking to play with a four-down and go rush. Even Vic Fangio is in on the craze.

Saleh, Fangio, and their ilk may not be blitz or pressure mavericks, but they picked up a trick or two from Ryan to tip the pass-rush game in their favor. With just a four-man investment in the pass-rush — from a set of down-four, pass-rush specialists — a defense can still force the offense into a favorable protection while sinking eight guys into coverage. It’s hard to tip the scales any further in your favor.

But that new-fangled stuff is old hat to Ryan. He didn’t just utilize a lone mugger. He broke down each team’s protection preference. He studied the quarterbacks. He studied each lineman. Obsessively.

“There were times when we knew exactly how we wanted to block them, and yet we were still confused,” Ladanian Tomlinson said of Ryan’s 2010 defense. “I don’t know how they did it. We kept saying, ‘Something’s gonna work; we’re gonna get it.’ Come the fourth quarter, we didn’t get it.”

There was nothing to get, Ladanian. Ryan was already a couple of chess moves ahead.

Part of Ryan’s pre-game scouting was scouring every single detail of an o-lineman’s stance to get a tell. Do they change their down hand based on run or pass? How much weight do they put on their front hand? What is going on with the off-hand? At the pro level, that stuff still shows up, despite every effort made by the offensive staff to combat it.

Every defensive staff runs through that sort of rudimentary prep. But Ryan tailored his pass-rush plan not only to those generic tells, but to the specific weaknesses of each lineman against each defensive look — and then tailored his pressure plan to exploit those weaknesses.

You will have heard it before, but offensive line play is all about the weak link. Teams design their pressure plan around the weakest link, hoping that if that caves in, then it will pull the rug from everyone else along the line as they scramble to help. Pressures are largely designed to penetrate the interior gaps in the NFL. How you get to that penetration, though, can come in many shapes or forms. What Ryan initiated, and is now standard practice, was keying not on the weakest link (the worst player) but the weakest link against every specific defensive action. Who struggled most with power? Who with speed? Who struggled against someone who could cross-face quickly? What about blitzers from depth? Who was fine in a quick set but struggled to sink against power. Which player struggles with two-on-one conflicts? Which duo passes things off the best? One player (the center, say) may be the weakest against one design, but the strongest against another. And how does that tie to the strengths and weaknesses of the quarterback? Can he slip and slide in the pocket? Does he try to hit the middle-of-the-field against pressure? Is he a second-reaction guy or a hot-route darling? Ryan would tweak his pressure paths — and the relationship to the coverage — to the opposition.

That may sound obvious. It wasn’t at the time. Defenses blitz based on tendencies and the down-and-distance. They had a handful of preferred looks, rarely showing a different pre-snap presentation to get to their preferred designs. Ryan’s obsession with protections and the individual protectors fueled his best work. If you know that a left guard, for instance, struggles to pick pressures from depth when in a half-slide but is fine when it’s man-to-man protection and he knows who he is taking on, then best to present a pre-snap shape that forces the offense into that half-slide protection with a player steaming towards the left guard. The offense may know who they’re supposed to be blocking, but struggle all the same. That is grabbing the initiative back.

Ryan was precise with his team, too. The details mattered. He was a key leader in switching up the mechanics of the two-man pressure dance, elevating the use of a single blitzing linebacker into an art form. Ryan was frustrated with simple linemen-to-linebacker pressures. They didn’t hit quite right. He saw the problem: the first-level defender was cutting across the face of his block too quickly. It looked like a run stunt, and handed the initiative back to the offensive line to pick up the lineman and linebacker before the blitz hit. So Ryan built in heavier jab steps, forcing his linemen to work upfield first and command the attention of an interior lineman before working across the face, with a linebacker screaming downhill tight to their ass.

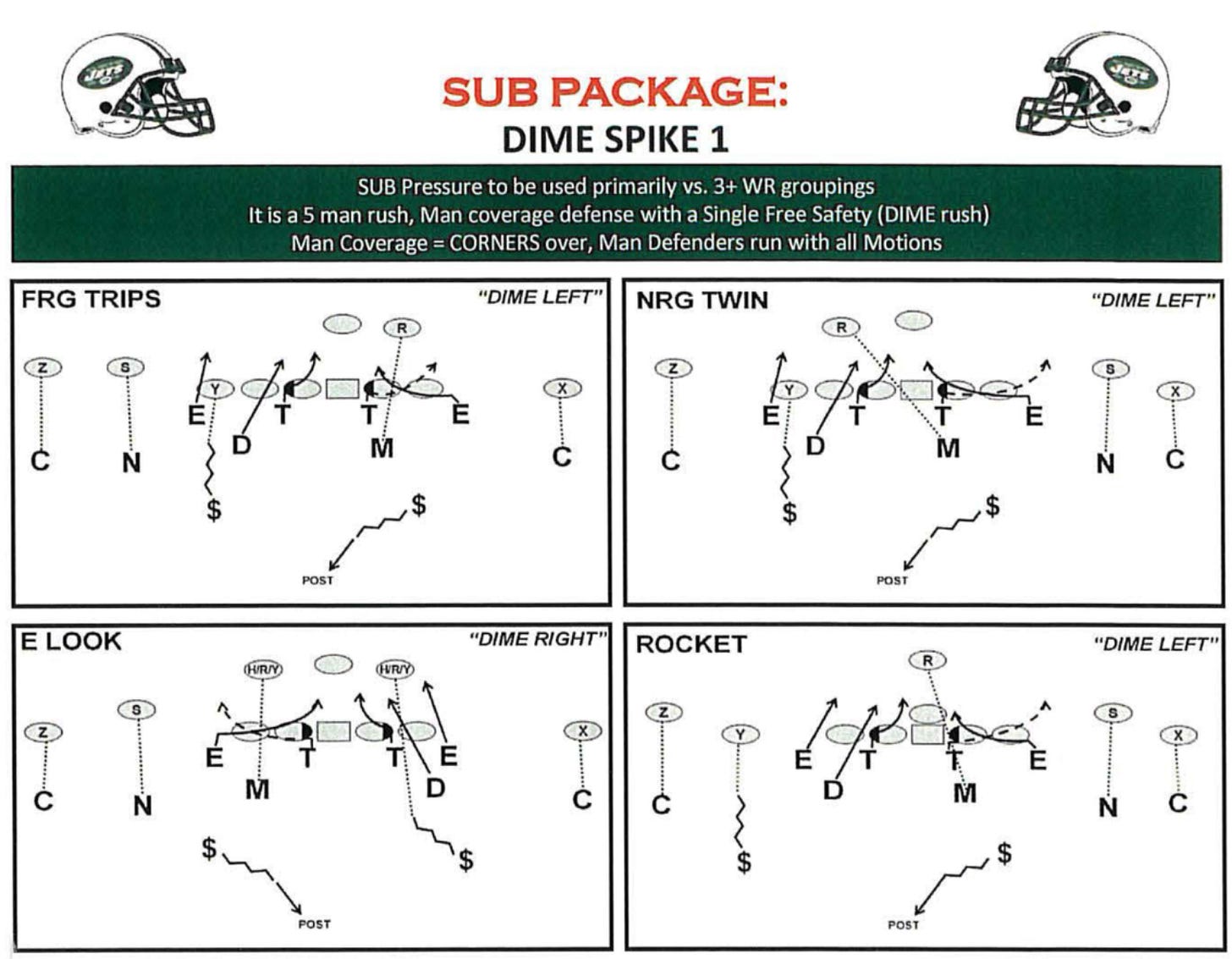

Chuck Pagano, who worked with Ryan for three years, referred to those single “spike” pressures as a play of faith. Linebackers had to have faith that the down linemen would eventually wind up in the gap they needed to be in, even if they didn’t rush there with their first two steps. Trust your teammate, and the thing will hit. No thinking. Just doing.

Ryan’s favorite linebacker blitz, now omnipresent, was the key to Bart Scott totting up 25 sacks in his career. Coaches have continued to iterate on its mechanics (mostly the coverage and rush balance), but the base remains Ryan’s invention. That two-man dance is crucial for modern defenses — and was on the upswing in 2024. Yet a ton of teams are still struggling to figure out that rudimentary two-man tango decades after Ryan laid out the blueprint.

Start stringing those ideas together, and you see that, intuitively, Ryan put together the building block principles of the game we see today. From overload fronts to the craftiest blitz designs, to how those paths are drawn up, when they’re called, and the mechanics within those calls, it all flows back to Ryan.

Pressure was everything to Ryan: creating physical pressure on the backfield with a cavalcade of blitzes and different pressure approaches; creating mental pressure in the minds of opposing play-callers and quarterbacks.

Ryan wasn’t always the originator of ideas. But he pioneered an approach that blended a heavy dose of blitzes, zone-pressures, creepers, read blitzes, overload fronts, simulated pressures, and multiple fronts into a single cohesive scheme. He siphoned all the best stuff from those who had gone before and created truly innovative designs. Somehow, he was able to take what was known, what was revolutionary, and synthesize it into a legible, teachable scheme, sometimes through sheer force of personality; Ryan is among the greatest whiteboard-to-on-field coaches in history.

Plus, Ryan was a convert to packaging blitzes — dressing up the same paths in different ways. He would tailor paths not only to the protections he was looking to break, but to his players. Everyone was given their own path. Where are they at their best? Let’s give them their own blitz. We will name it after them. That way, our package jumps from a handful to hundreds with minimal installation. For a play a game, or at least during the install phase, everyone will feel like the MAN.

(The subtle differences in the terminology may sound confusing. The definitions for sim pressures, creeper pressure, and zone pressures are not always standardized. This is what I roll with at TRO: Sending six defenders after the QB is a blitz; sending five defenders is a pressure; sending four but with an unexpected dropper is a creeper; a defense presenting like it will send five or six, but sending four is a simulated pressure. The ‘option’ blitz world can muddy the waters.)

Ryan’s pressure packages were also laced with disguises. Not so much on the back-end (more on that later), but in jumbling his fronts and using all eleven players as potential blitzers or droppers. For opposing quarterbacks, it was a clusterfuck. Who is coming? Who isn’t? Is what I’m seeing real? If I pick up on what is coming, I know it’s going to be aimed at the weakest player in my protection.

As the league has tipped into a pressure and disguise league, the best coaches have sought out those with a close seat to Ryan. Jim Leonhard and his Wisconsin staff built the most sophisticated “creeper” pressure defense in college football during his time as the school’s defensive coordinator. Offseason after offseason, Leonhard had been tipped for a DC gig in the NFL, including interviewing with the Green Bay Packers. Leonhard would have been taking the Packers job after… Mike Pettine. Leonhard’s defenses have been built on the backs of the units he played in under Ryan. While working with Ryan, Leonhard was first introduced to creepers, a pressure design where the defense sends four pass-rushers with an unexpected dropper, typically with one of those four pass-rushers coming from the second or third level. So it’s no surprise that Vance Joseph would call on Leonhard when he was looking to build in more creative pressure designs himself, and Joseph was hardly short of innovation in the pressure world.

Leonhard was given a PhD in Rex-ology during his time with the Ravens and Jets. It wasn’t just about blitzing and pressures, but an approach to the game. Ryan trusted his players. No matter the wonky-ness (or not) of the design, he gave them freedom. “Our playbook tells you where to be,” Leonhard said during his time in New York. “But you can begin anywhere so long as you end up where your task says you should be. How you get to the endpoint doesn’t matter. A lot of coaches don’t want to give players that freedom.”

Ryan’s “worry about where you end up, not where you start” philosophy to creepers gave his defense a natural sense of disguise. It didn’t matter if the play-caller dialled up the same call over and over again (as he often did). The sense of fluidity muddied the pre-game prep for opposing offenses: it’s the same path, but a different presentation? Is it a different call? The same call? How do we get a read on it pre-snap?

By embracing that freedom, Ryan lessened the workload on his players. There was less to take on board. It was the same path, the same techniques. But it upped the ante for the offense. They couldn’t be sure it wasn’t a different path or design. They had to prepare.

Leonhard embraced that idea with Wisconsin. And he has helped remould some of Joseph’s designs with the Broncos.

Joseph is one of the most potent safety blitzing coaches in football. It’s what he does. But even by his own standards, last season the Broncos let their safeties run wild.

The Broncos put together the highest Creeper rate of Joseph’s career — and the highest safety blitz rate in any season that he was not working with Budda Baker (not sending Baker would be a crime against football).

Joseph leaned into the freedom idea. The Broncos brought the same looks week after week, only with the safeties arriving from different spots at different times.

How about getting those safeties involved in some early-down, post-snap bear looks? Go on, Vance!

The Broncos under Joseph and Leonhard even dabbled with Locked pressures. Back in New York, Ryan and the Jets had the luxury of Darrelle Revis. To keep Revis where he was at his best, Ryan consistently churned through ‘locked’ coverages, sticking Revis in a one-on-one man-coverage dual while having the rest of his secondary zone up. It was a bid to get the best of all worlds, shutting down a top receiver, putting some natural disguise into the coverage, and keeping vision on the ball. After building in locked coverages, Ryan did what he did best: he plopped some pressure sauce on top. With Patrick Surtain, the Broncos can get away with similarly heinous concepts.

It’s hard to believe that Leonhard — and by extension Ryan — did not have an influence. That increased emphasis on creepers and secondary pressures is probably why the Broncos signed Talanoa Hufanga in the offseason and selected Jahdae Barron in the first round of the draft. The two will add more flexibility and dive-bombing instincts to a talented secondary.

Flores has charted a similar course. What more does Minnesota’s DC need to know about marrying his pressures with coverage? Well, adding Pettine allowed him to tap into a player-caller who was dialing this stuff up when Flores was still working as a road scout in New England. “Quarterbacks prepare like junkies,” Pettine said in 2012. “We create things they think they recognize — line up in something they think they saw on film a year ago — then we do something different.”

Even Flores’ vaunted read-blitz designs trace back to Ryan. Nick Saban is credited with designing the initial “rain blitz” look for Bill Belichick in Cleveland, before cranking up the style when he was the Dolphins head coach. But Saban credits the idea to a brainstorming session with Rob and Rex Ryan.

Ryan spent two seasons so enamored with the read-blitz idea that he didn’t even incorporate them into his playbook — a counterintuitive idea that only makes sense in the Rex-ys world. Seeking perfection, Ryan would simply tell players which pressures, which blitzers, and which linemen he wanted to read on a given week, owing again to his innate feel for a game from the sideline. Read blitzes were not just part of the generic pressure approach; they could be added to any design depending on the opposition.

He didn’t stop there. What were once fringe calls in Ryan’s Ravens playbook became the basis of his units in New York and Buffalo. And if you track the recent trends of the top NFL defenses, you see them all with Ryan’s units, 25 years before they were en vogue.

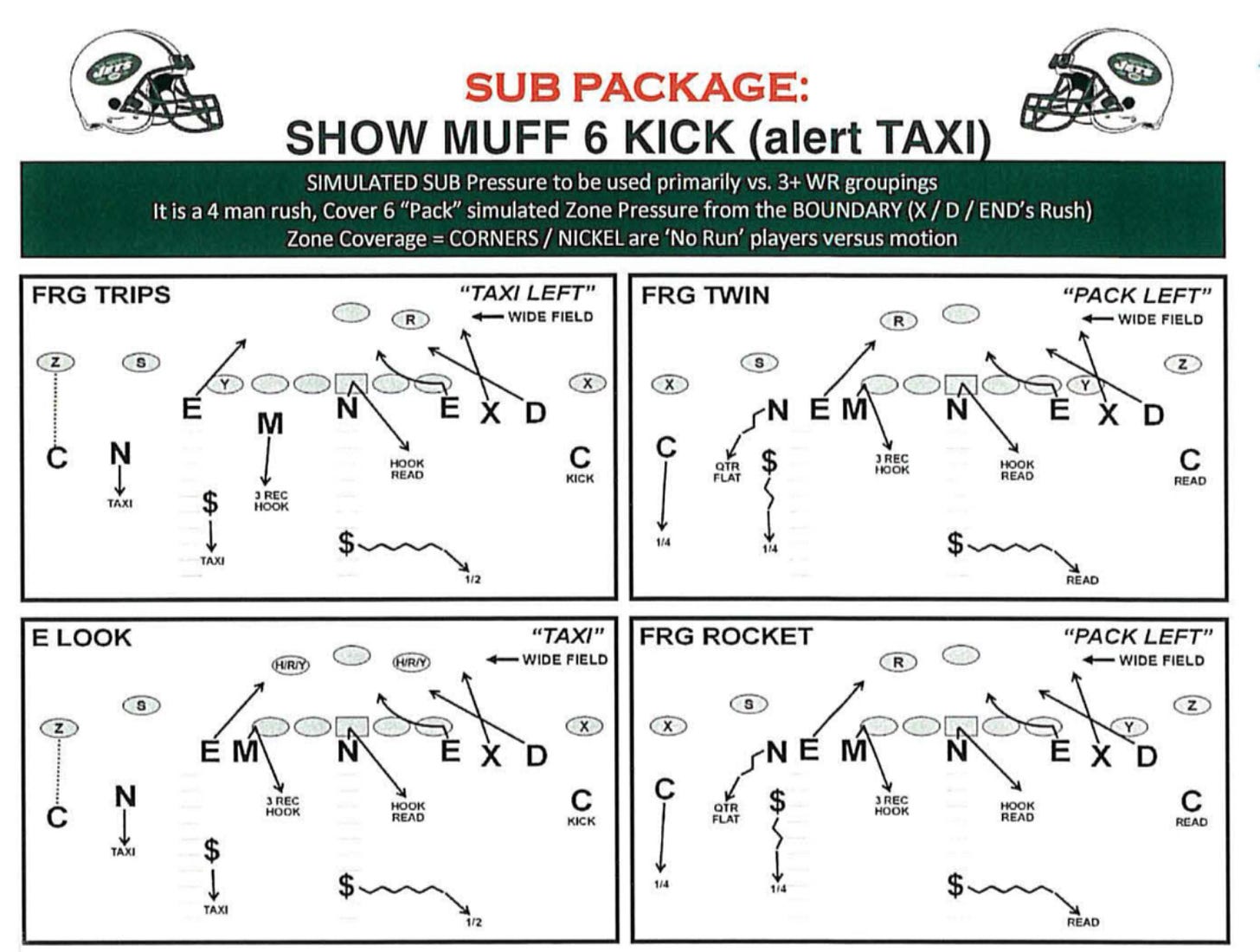

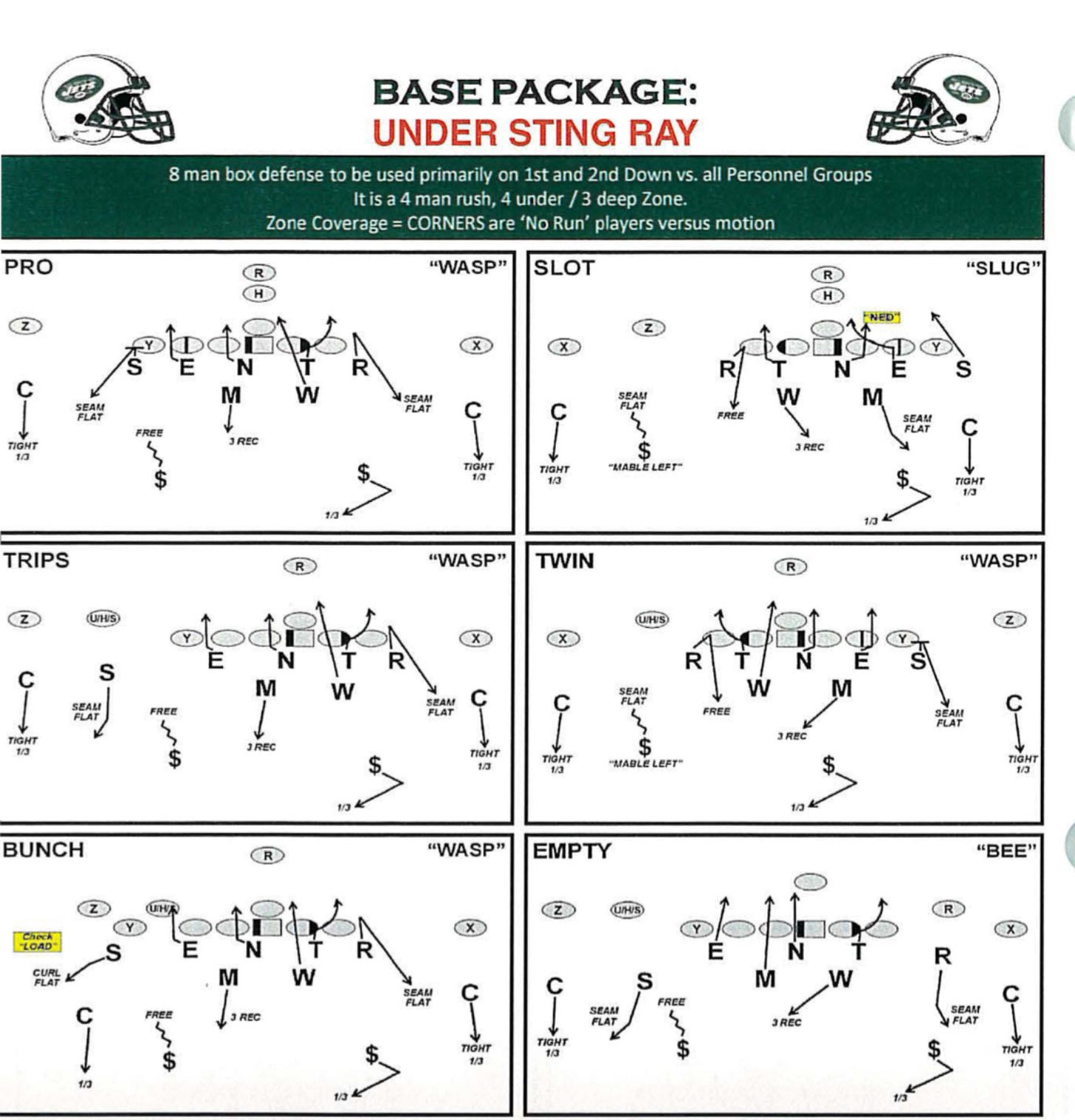

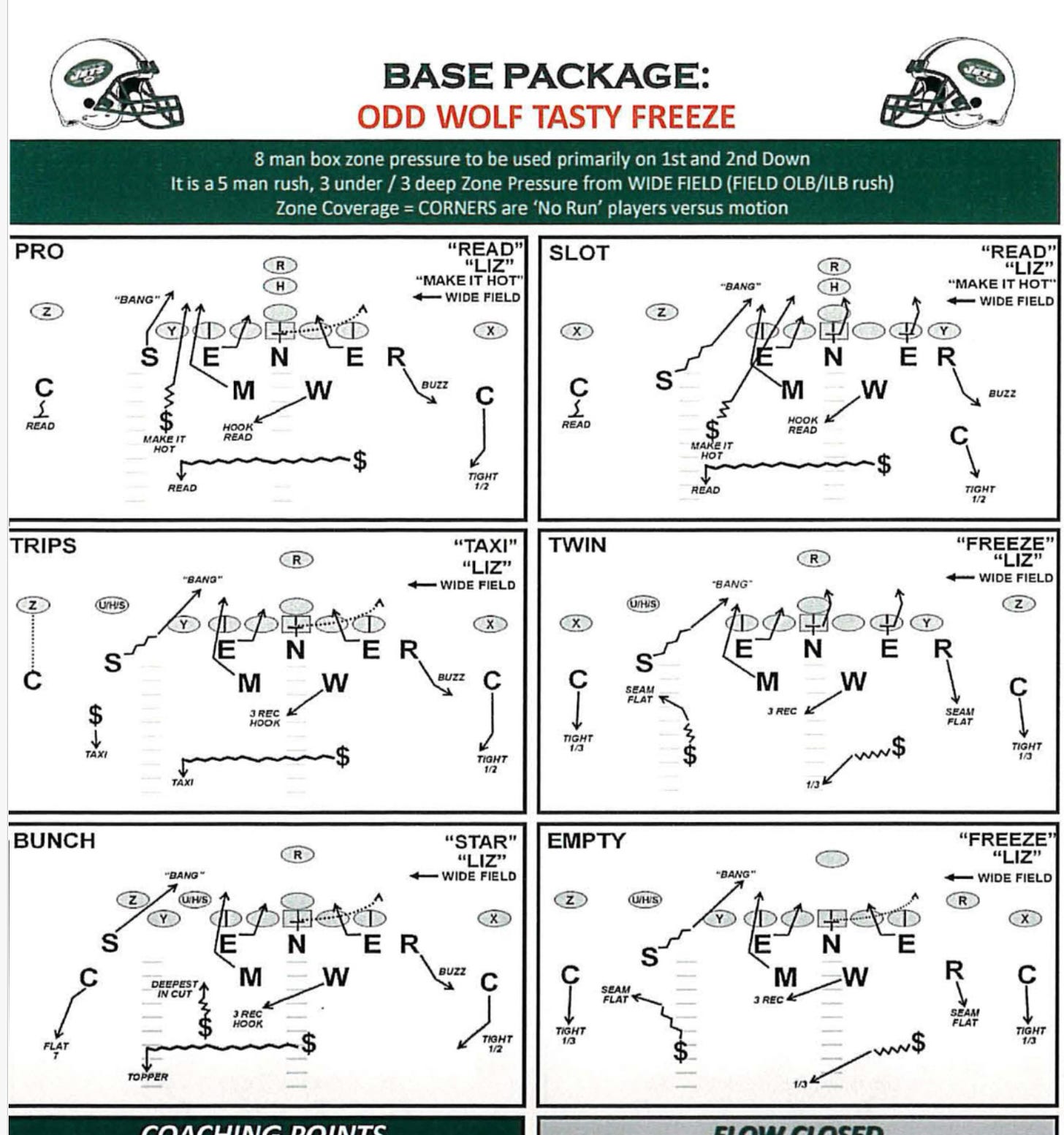

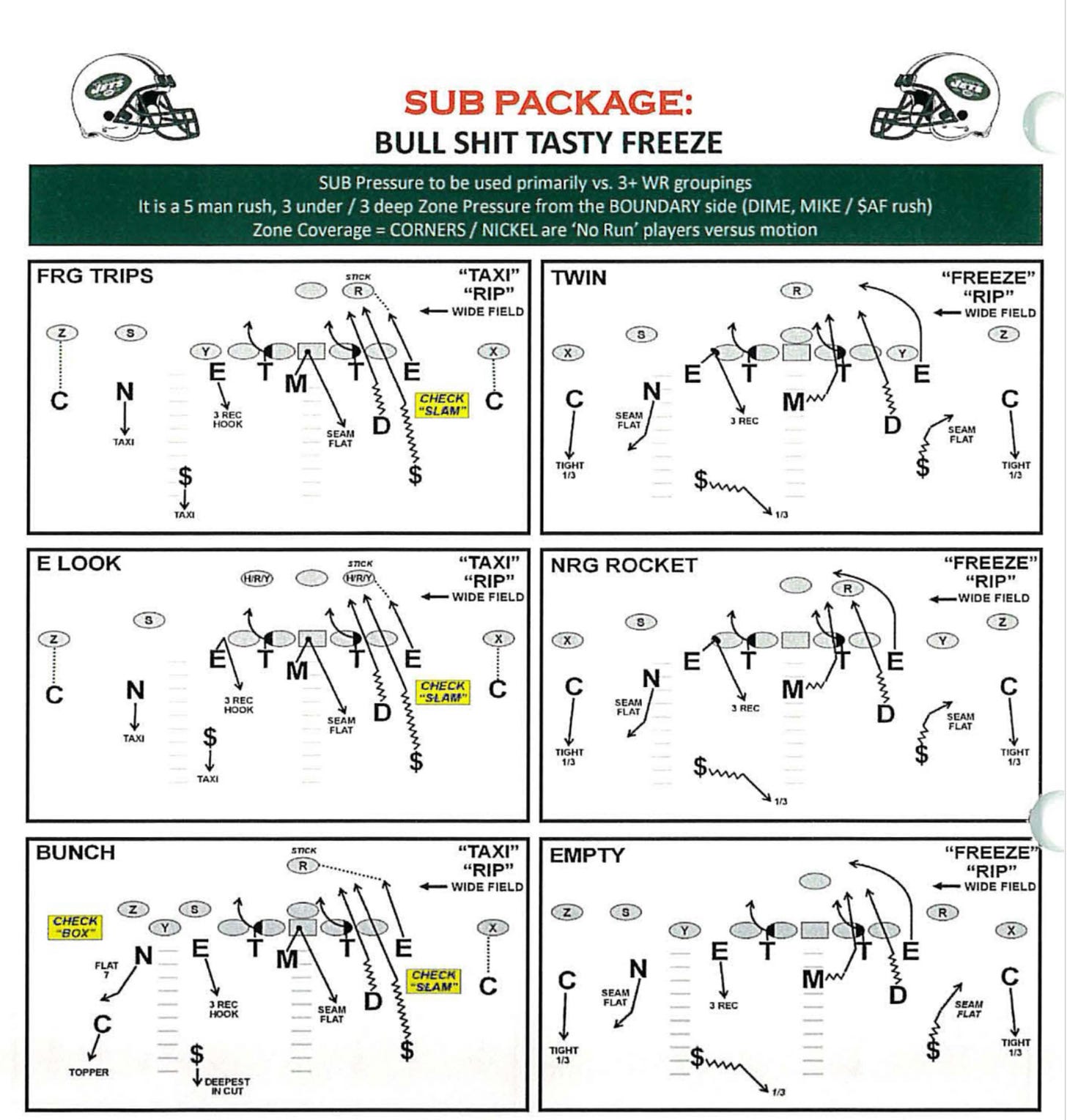

Cast your eyes back through Ryan’s old work, and you find the building blocks of the best defenses in 2024. Ryan was using simulated pressures – was calling them simulated pressures – before they even entered the wider footballing lexicon a decade ago.

What about the early-down, lone-plugger stuff to help spike the run game and fend off the threat of play-action? There it is.

There are all the sims and creepers you can think of:

Some were so wackadoodle even Ryan had to say they were bullshit.

There are those single-mug looks:

Double B-Gap penetrations? Go on then.

There are heavy overload fronts, sometimes coming as a four-man rush and sometimes with five or six players in the rush. There are full overload designs, splitting the line of scrimmage in half with one end dropping out and the rest in attack mode. There is even a nod to those “read” pressures, by design rather than in-game feel:

How about getting to a “Bear” front post-snap, as is now the want of most coaches? He’s got those too. What about those locked coverages? You bet. How about pairing that with some heat to the funnel side?

Come on, Rex. Save some for everybody else.

You want one of Joseph or Macdonald’s “Casino” blitzes? Rex has you covered.

Seriously. Grab yourself a cold one and pull up some of Rex’s archive. It’s a fun evening.

The names of Ryan’s designs have seeped into coaching folklore. If you are a scheme dork, you will associate Saban with the words “Rip” and “Liz.” Entire schemes have been devised out of Ryan’s “Favre”, “Bledsoe”, “Sting Ray”, and “Tasty Freeze” designs. Heck, even the practice of naming pressures after quarterbacks started with Ryan — and is now the standard for most defenses.

Here is Mike Macdonald, current defensive wunderkind, hitting a Favre pressure against the Bengals in the playoffs:

Track the number of free runners that defenses engineered in 2024, and it’s remarkable how many come from the “Bledsoe” or “Sting Ray” concepts — or a combination of the two known as B-Sting.

Penetrating the B-Gaps is the name of the NFL game. And no one devised more ways to get pressure screaming home into a quarterback’s face than Ryan.

Macdonald’s defensive system is less exotic than Ryan’s. He focuses on fewer pressure paths than Ryan and his cohort, relying on packaging those paths in different ways to help streamline the teaching process for his own players while keeping offenses off-kilter. Yet the roots of Macdonald’s blitz and pressure devices stem from Martindale’s time as Baltimore DC and reach back to Ryan’s unit in 2006. Even running those pressures as packages goes back to Ryan, only Macdonald has more presentations within his packages.

Here is Macdonald rolling out One Double Rat with the Seahawks, which plays on the illusion of pressure to get a defense into a drop-eight coverage with a potential late tagger.

Where have we seen that before? Oh, here’s Ryan:

Coaches, like Macdonald, have taken Ryan’s principles and pushed them to new heights — like, I don’t know, turning a single-rat sim pressure into a double rat with drop-eight coverage (Macdonald is really good!). Some have turned the dials up, using Ryan’s designs as the base of their entire pressure approach. Others have tweaked the fundamentals to match current defensive needs. That could be tweaking the front structures or coverage behind to fit their personnel or trends they’re facing across the league. Still, the root paths remain the same as the ones Ryan was rolling out in 2006 and 2012.

The main change: where Ryan based his pressures on three-deep, four-under zones, Flores, Joseph, Macdonald, and the like have switched to two or four-deep coverages. That allows them to maintain their disguise and to keep the integrity of their split-safety presentations. But they are cover versions of Ryan’s original album.

When Dave Aranda rocked up as the defensive coordinator at Utah State in 2012, he probably didn’t think he would change the landscape of college football. Looking for a way to combat the spread era, he brought with him a new vision for defense and cutups from two coaches: Rex Ryan’s Jets and Vic Fangio’s 49ers.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Read Optional to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.